the divine discontent

perfection is impossible, but I'm chasing it anyway ✦ plus Flaubert, Proust, and that one Ira Glass quote

The most fulfilled people I know tend to have two traits. They’re insatiably curious—about new ideas, experiences, information and people.1 And they seem to exist in a state of perpetual, self-inflicted unhappiness.

These people tend to have a project they’re working on. An essay. A poem. They’re reading Wittgenstein for the first time. Or rereading Proust. They’re rehearsing for a dance performance. Learning about carbon capture technologies. Making a track in Ableton. Knitting a jumper. Testing out a new recipe. Improving their Cantonese. Taking a painting class…

They’re serious about the project, although they may exhibit some self-consciousness, some hesitancy, about how badly they want it to go well. If you catch them on a good day, they’re full of freshness and vigor and excitement—an infectious enthusiasm that makes you a little more lighthearted, and a little more excited about whatever projects you have in your life. But if you catch these people on a bad day—well. I’m stuck, they’ll say. The project’s not going well. I’m not getting any better at this. It’s not as good as I want it to be.

And if you take this dissatisfaction at face value, it may seem as if the project is the problem. Why do they want to write so badly, if they’re always complaining about it? And when their keen curiosity leads them to discover better writers, artists, thinkers, musicians—that’s when they became painfully, overwhelmingly aware of how far they are from achieving greatness. What’s the point of taking piano lessons if you’ll never be Glenn Gould?2

But it’s this restless pursuit of greatness, even when they feel demoralized and inadequate, that shapes their lives and makes things interesting. So let’s not call it dissatisfaction. Let’s call it a divine discontent.

The divine discontent

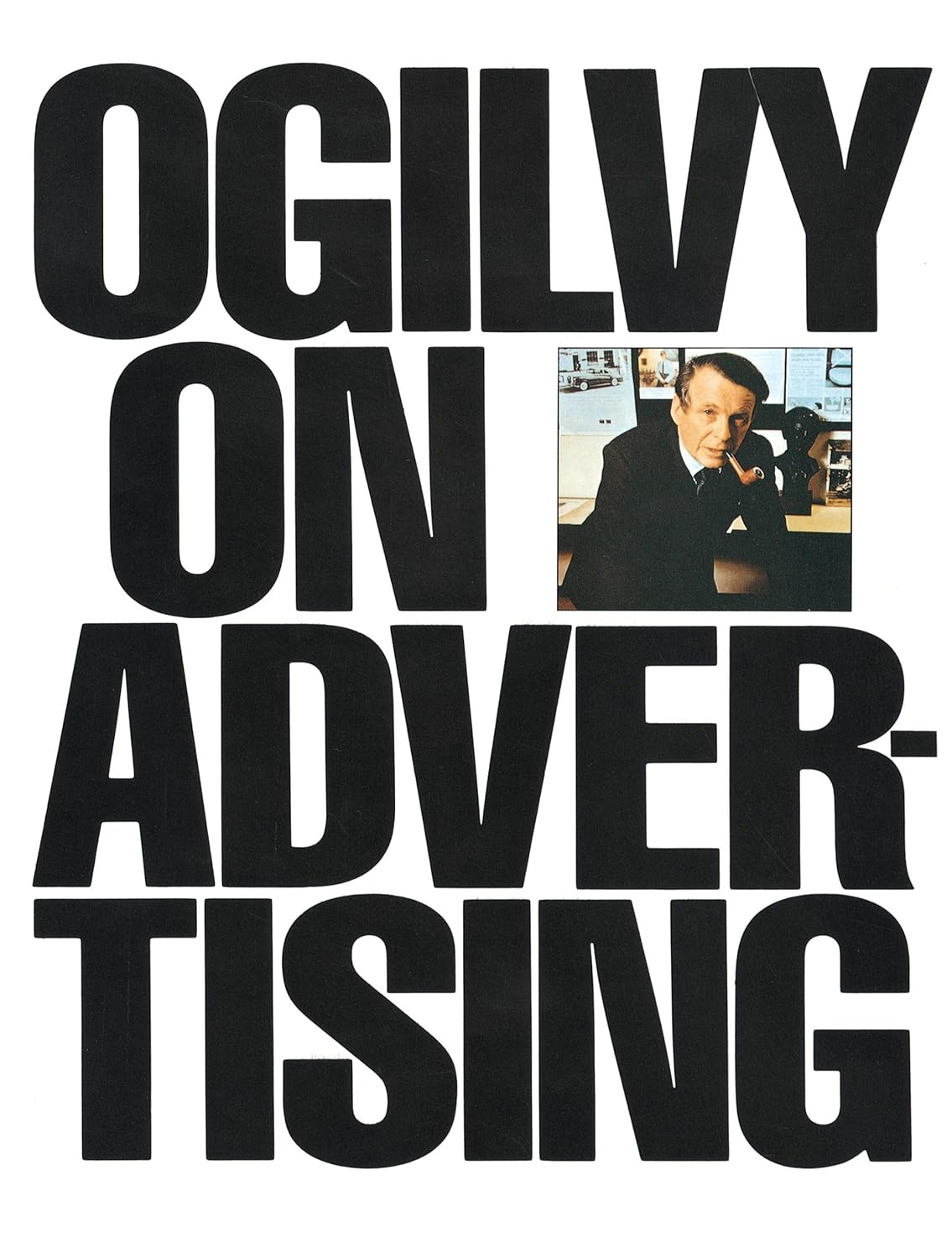

I’ve borrowed this concept from David Ogilvy, who’s often described as the “father of advertising” because of his enormous influence on the style, visual language, and voice of 20th century American ads. (The TV series Mad Men is, in many ways, about the world Ogilvy created.) The agency he founded in 1948, Ogilvy & Mather, became well-known for their iconic campaigns for brands like Rolls Royce, Dove and American Express.

The agency’s success, Ogilvy insisted, came from their commitment to excellence, ambition and humility. “We have a divine discontent,” he once wrote, “with our performance. It is an antidote to smugness.”

To me, divine discontent is about cheerfully seeking out dissatisfaction. It’s choosing to ask, What could be better? What can I improve? It’s a feeling that practitioners across many fields—in literature, art, music, performance, film; but also the sciences, engineering, and mathematics—can relate to.

But let’s look at writers, in particular, and how they commit themselves to remaining curious and dissatisfied with their work:

Divine discontent is about patient, unyielding discipline. It’s Flaubert’s four and a half years spent writing Madame Bovary, and complaining to friends and lovers about how displeased he was with his writing. “Yesterday evening,” he wrote to his lover, Louise Colet, “I started my novel. Now I begin to see stylistic difficulties that horrify me.” He had begun other novels before, but abandoned them. With Madame Bovary, he persisted—although his exacting standards led to very slow progress. As Lydia Davis writes, in the introduction to her translation of the novel:

Because [Flaubert] discards a good deal of material, and prunes back severely the material he keeps, he produces very few finished pages—he variously reports one page per week, one every four days, thirteen pages in three months, thirty pages in three months, ninety pages in a year.

Divine discontent is about aspiring to greatness, to be unembarrassed and indomitable in your ambitions. It’s Helen DeWitt studying classics at Oxford, before realizing that she wanted to write a great work of literature, and not just write about them. She left academia and worked several odd jobs while finishing her debut novel, The Last Samurai, which is, according to the critic Christian Lorentzen, one of “the finest novels published this century.” In his profile of DeWitt, Lorentzen writes:

She realized she wasn’t interested in writing about writers writing about writers writing about Euripides. She wanted to be Euripides.

Divine discontent is revealed in the tireless, mundane work of improving one’s craft. It’s Lydia Davis, the renowned short story writer and translator, writing constantly in her notebook—and revising her notebook entries for coherence, clarity, and style. In her book Essays One, Davis asks:

Why do I revise the notebook entries? I’m not sure, but I will guess. For one thing, it is hard for me to let a sentence stand if I see something wrong with it. Even when I’m writing a grocery list it is hard for me not to correct a misspelling…

There is also the constant practice I get from revising notebook entries…by getting a certain description exactly right, I am sharpening the acuteness of my observation as well as my ability to handle the language. So there are many ways to justify working hard on one sentence in a notebook, a sentence that you may never use.

Discipline, aspiration, and revision: These are psychological habits that many people (not just renowned writers!) experience in their day-to-day lives. The tendency to revise, in particular, seems especially common with people who experience a divine discontent.

Once you’re used to looking for the flaws in your work, and finding small ways to improve, it becomes a habit. The divine discontent can’t help but show up in ordinary life and even situations that aren’t explicitly about making art, writing an essay, and so on. For example:

I reread an email I’ve sent, and find that I’ve used too many em dashes—a bad stylistic habit that I’m trying to excise from my essays.3 The essays are “real” writing, and the emails are not…but still, I’m upset!

While on vacation, I write a postcard to a friend, and find myself scrutinizing the uneven margins around the message I’ve written. I mourn the poor typographic choices I’ve made, wishing I’d left-aligned the address of the recipient more neatly.

I’m preparing dinner at home with my girlfriend. I make the salad, improvising with whatever herbs we have in the refrigerator, and make the vinaigrette without measuring anything. She tries to recreate a pasta dish she tried at a restaurant once. We sit at the table and critique our efforts. The vinaigrette is too sharp, I tell her. Next time I’ll use a rounder, milder vinegar, or balance the acid out with some maple syrup. Meanwhile, she’s evaluating her dish and deciding that it needs better tomatoes, more salt, more tarragon.

There’s a difference, of course, between caring deeply about quality and being excessively critical! But this instinct to critique my own work, to understand what fell short and fix it—that’s the divine discontent. Personally, I find that it’s genuinely fun to live like this. It makes life interesting! It means there is always something to care about and be passionate about.

As a young writer, Davis writes,

I cared very much whether a journal entry was well written or not, and if I happened to read it over, I would always revise it in small ways until it was as good as it could be, whatever its value. I still do this.

This desire to improve, as I’ve said, appears across all fields. The cerebral and more legibly intellectual fields like writing, of course—but it’s just as important in areas like dance, where physical practice, rehearsal, and repetition are central to achieving artistic excellence. It’s repeatedly emphasized in the acclaimed choreographer Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit. Early in the book, Tharp shares a list of questions that every creative should ask themselves, along with her responses. Here’s one of them:

What is your creative ambition?

To continually improve, so I never think “My time may be over.”

Accidents of fate

Part of the appeal of books like Tharp’s The Creative Habit, and Lydia Davis’s Essays One, is that they reveal the beliefs and habits that made someone so good, so obviously capable, in their vocation. They tend to reveal, too, why they chose these particular vocations: choreographer (Tharp) and writer/translator (Davis).

The divine discontent needs a focus—it needs to dwell in one or more disciplines that feel especially meaningful and potent to someone. The world is endlessly, infinitely interesting, but our lives are finite! So we have to choose what we want to improve in. Our passions are partly the result of conscious decisions (we might learn to sew, say, or learn another language); but they often begin, I think, in an accident of fate.

I’d love to know what your accident of fate was! But here’s mine—and we’ll need to return to David Ogilvy to explain it. Part of his influence comes from two books, Confessions of an Advertising Man (1963) and Ogilvy on Advertising (1983), which laid out his approach to advertising, and how clear, resonant language and crisply executed graphic design could turn a mere commodity into something desirable. But the books weren’t just about how to sell products. They were about understanding what people wanted from the world, and how you could respond to that, in writing and design. They showed me how language could draw out some obscure emotion from a reader—pride or satisfaction or longing or desire; or the way images could arrest a viewer, with a striking and fresh beauty, and make them linger on a page.

At some point in my childhood, I came across a copy of Ogilvy on Advertising in my family’s garage. I’m not sure why we owned the book, since neither of my parents worked in advertising.4 But there was a community center near us that hosted a used book sale, and on the second Saturday of each month, my father would collect all the quarters and dimes in our home, gently chide me out of bed, and we would go shop for books together.

We must have bought it because of the cover: the arresting sans-serif text, and a modestly-sized photo of Ogilvy himself, gazing steadily at the viewer. I don’t know if my father ever read the book. But I did. Ogilvy on Advertising explained how to design a good ad, how to write compelling copy, how to find the image that would speak to viewers. I learned something from this: I learned that design mattered, that writing mattered.5 And it taught me a particular ethic for doing great work. I learned to pay attention to everything, to obsess over quality, and never rest on my laurels.

The pursuit of unhappiness

But living like this—with a constant, compulsive awareness of your flaws—can be tiring! The divine discontent can easily tip over into self-hatred and paralyzing perfectionism. How can you be someone with a project, with ambitions, with taste and aspirations…and not make yourself wildly, neurotically unhappy?

It’s especially hard when you’re just beginning to work on your craft. “I love to study the beginnings of things,” Tharp writes in The Creative Habit. “The first steps are the most interesting ones—when you’re just beginning to find your way into a problem, whether it’s artistic or philosophical…when you don’t yet know what you’re trying to solve and how you’re going to solve it.” It’s an exciting time, and a terrifying one. Even for an accomplished choreographer! In another Q&A in the book, Tharp writes:

At what moments do you feel your reach exceeds your grasp?

I always, always feel that at the start. But you get lucky now and again, so I reach anyway. That’s why I study beginnings, so I can deal with those fears.

Tharp’s words resonate with another well-known quote, from the radio producer Ira Glass, on feeling disappointed by your own work:

All of us who do creative work…get into it because we have good taste. But there’s a gap. For the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making…It’s not that great. It’s really not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambition to be good, but it’s not quite that good…[but] your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you…

Everybody I know who does interesting creative work…went through a phase of years where they had really good taste and they could tell what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be. They knew it fell short.

If you’ve trained your taste on great works, it’s disappointing to realize what you’re capable of: Dull, impoverished, and painfully mediocre imitations. It’s easy to give up at this point. But Glass exhorts us, instead, to keep on going. That feeling of disappointment? “Everybody goes through that,” Glass notes. And the correct response is to

Do a lot of work — do a huge volume of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week, or every month, you know you’re going to finish one story. Because it’s only by actually going through a volume of work that you are actually going to catch up and close that gap. And the work you’re making will be as good as your ambitions.

In short: Practice. Start projects. Finish them. Persist through the terrible work, the inadequate execution, the failures. There’s another book, written not by Ogilvy but by those who came after him at Ogilvy & Mather, that has something to say about this.

The Eternal Pursuit of Unhappiness, published in 2009, wasn’t written for the public. It was meant to be distributed internally—to new employees at the agency, I think. Before the Internet Archive made a scanned copy available (only this summer!), there were only a few copies available on eBay, and they were all quite expensive. But almost 10 years ago, I came across a blog post that quoted from and paraphrased the book in a particularly elegant fashion. What struck me then, and what I return to now, is this:

Persistence

Dogged determination is often the only trait that separates a moderately creative person from a highly creative one. Never give in, never give in, never, never, never, never. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.

It’s easier to persist, I think, when you see your work as a practice—an ongoing process of improvement—instead of focusing too much on any particular project. No project will be perfect. But each project can be better than the previous one, and each project can sharpen your skills and deepen your commitment to a craft.

“We are,” the blog post concludes, “what we repeatedly do. Being very good is no good. You have to be very, very, very, very, very good.” And this, I think, characterizes what the divine discontent feels like. Even if the project you’ve just finished is very good…well. Maybe it could be better. Maybe your approach, your craft and your thinking can be refined. Being very good is no good. You have to be very, very, very, very, very good. And that’s what the next project is for.

I’m writing all this to explain (to myself, maybe, and to you) why I keep flinging myself into pursuits that are destined to make me unhappy, gloriously and sublimely unhappy. And why I’m most fulfilled this way—why this pursuit of unhappiness is in fact the thing that makes life meaningful!

If you can relate—if the divine discontent has shaped your life as well!—I’d love to hear. Reply to this email, comment below, DM me…let’s be tremendously, spectacularly dissatisfied together!

For more posts on creativity, insecurity, effort, and revision—

Four recent favorites

Caroline Polachek, the last stylish pop star ✦✧ At the intersection of music and food ✦✧ At the intersection of graphic design and literature ✦✧ On being butthurt

Caroline Polachek, the last stylish pop star ✦

Speaking of dissatisfaction—what really distresses me (in a very low-stakes, largely frivolous way) is how few genuinely stylish musicians we have. But you know who always looks good? Caroline Polachek! For an Art Basel event, she showed up in Yohji Yamamoto.

At the intersection of music and food ✦

While everyone else is working at the intersection of art and technology, the producer and DJ Yu Su is working at the intersection of sound and food. I loved this article, by the culture journalist Joel Hart, about a recent event Yu Su hosted at a listening bar in London, where guests were invited to experience a set menu and a soundtrack together:

She arrived at a concept she calls “polyphonic eating”…to “push to the other side of what conventional going out to eat experience is like in modern societies,” she told me over the phone. Polyphonic music involves multiple sounds or voices, but it wasn’t immediately clear to me what the concept might mean when applied to the act of eating. “It’s more like a performance,” she continued. “I wouldn’t call it a supper club.” She also pointed me towards Pauline Oliveros’ concept of deep listening, which she took inspiration from, that calls for active listening to achieve greater connection with the space and bodies around you.

In one of my earliest posts, I wrote about Yu Su’s album Yellow River Blue (2021), which I spent half of December listening to! It’s truly lovely:

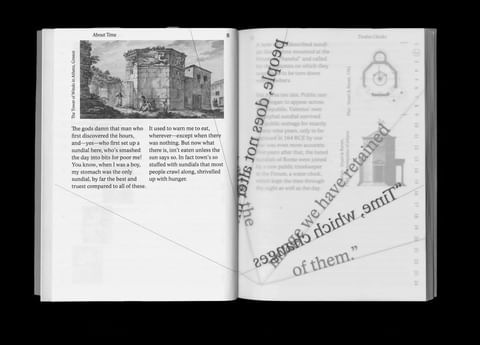

At the intersection of graphic design and literature ✦

I loved ‘About Time,’ a project by the RISD graphic design student Coco Li that’s inspired by Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. (It is, as you may already know, my favorite novel in the world.) Li designed a book that uses sheets of vellum paper to reflect the layered effects of memory and time.

On being butthurt ✦

I loved the novelist and journalist

’s latest newsletter installment, “On Being Butthurt,” which is partly about all the advice that writers receive about keeping a notebook (it’s harder to follow this advice than to give it!)…and it is also about the kind of envious, seething resentment that often shows up when we try to learn from other writers.“I have a memory from my youth,” Batuman writes, about “being depressed by multiple famous US-American essays about the necessity, for any writer, of ‘keeping a notebook.’ They always made me feel bad.” One of those essays, the appropriately titled “On Keeping a Notebook,” is by the iconic Joan Didion—whose glamorous, stylish example has terrorized generations of young women writers:

I usually feel a little bummed out when I read Joan Didion…with this particular essay, I felt some visceral annoyance/despair at the opening scene…[which] described a life of unknown dignity and autonomy and literariness…

My inner fourteen-year-old is still like: (a) “Why is she complaining?”, and (b) “How am I supposed to keep a notebook when I never go to bars, leave men, or take drugs?”

Here we are back at butthurt—its circularity. One person talks about how their lack of a safety pin is menacing their lunch in New York, and another person is like, “You’re having lunch in New York?” There’s a generational dimension, too. As a young person, it is indeed infuriating to be expected to admire “cool” things that are made by people who seem to be part of a huge adult conspiracy to prevent you yourself from doing or making anything. Then maybe you grow up and start making things… and if you’re lucky, your stuff becomes part of the adult conspiracy, and is foisted on young people, who sometimes utter a murmur of complaint—which you naturally protest for several hours in your heart—and so it goes.

Batuman moves from Didion to Proust to Shlovsky—oh! I should mention I posted a note about his “Art as Technique” essay recently:

—but back to Batuman! Who, in this lovely post, moves from writer to writer to writer, thinking about what we can learn from them, even—maybe especially when—they irritate us, with their rarefied and inaccessible lives. And how we cope with the feeling that all these successful, established writers had it easier than us. They were more privileged (sometimes this is true; sometimes it isn’t!); they had effortlessly interesting lives.

This feeling of “butthurt,” Batuman explains, “separates people from their natural allies.” But if we can find a way to feel less annoyed with these writers, we might find that there is something we can steal from them—some lesson, some inspiration.

Thank you, once again, for reading this newsletter! I’d love to hear from you. And please do share this post with friends, lovers, collaborators, crushes, exes (actually, I don’t recommend this!) if you think the concept of divine discontent will resonate with them, too.

If you’re working on a project right now, I hope that you get as close as possible—given the resources available to you, the time you have, the energy, the skills and material—to satisfying your taste. And if not…there’s always the next project.

Very fulfilled people tend to be delighted by gossip, too—not because they’re particularly mean-spirited, but because gossiping about people’s lives and love affairs is the best way to be a “student of the human condition,” as I said to a friend recently.

I define “gossip,” by the way, as including lighthearted and frivolous topics! But sometimes gossip is more emotionally and ethically complicated. In those cases, it’s best to gossip with people who accept the complexity of humanity and the conflicting ethical demands placed upon us. I liked what Rachel Connolly, in an essay for Hazlitt, had to say about this:

I like [gossiping]…in an environment in which everyone accepts the ambiguity of people and the things they do. This has been a respite from the world of social media discourse, where none of this complexity exists, and instead everywhere you look there are self-appointed priests, castigating sinners.

This is the key question animating Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser (1983), where an unnamed pianist meets a young Glenn Gould. He immediately recognizes Gould’s genius, and is so profoundly demoralized that he quits playing piano—despite having considerable (just not Gould-level) talent himself.

The pianist who quit is the narrator of the novel, and he repeatedly insists that it simply wasn’t worth it to continue, to try, in the face of such superior talent. But when I read the novel, I felt tremendously sad for the narrator! Why would you quit something that gave you pleasure (although maybe it didn’t give him pleasure? I can’t remember now) simply because someone else might be better? It’s a self-destructive tendency to quit just because you’ll never live up to an ideal.

It’s not going well! I love em dashes, I rely on them, I can’t write a one-paragraph without them!

My parents weren’t particularly interested in consumer culture, either. They weren’t materialistic at all! I, sadly, have strayed far from their values. I love things, objects, commodities. Tragically.

There were other books I encountered, years later, that shaped me even more explicitly! One of those books was Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller’s Design/Writing/Research, which includes several essays on design history, theory, and practice. Each essay is designed in a different way, so that the essay on deconstruction is also a visual deconstruction of a traditional page layout, and the essay on typographic history begins in all capital letters (no periods, no spaces), reflecting what Roman text carved into stone looked like. Lowercase letters, along with other features like italics, show up later—once they’ve been invented.

It’s such a great book—and I love the title! It really reflects the person I want to be, and the kind of practice I want to have. Designing things, writing things, researching how to do both well…

Celine, thank you for this piece. I just published my first ever (!) fiction story in a literary magazine, and I was horrified that the piece they selected was the one that took the least amount of effort, pain, frustration to write. Really, THIS was the one they wanted to put out in the world? It could be so much better, and I has many others that *were* better! My source material was my dreams, and it felt like cheating, like I didn’t really write it. And in reading you and talking to some creative friends, I realize that it’s not that the story was effortless, it’s that I had spent my lifetime on my writing practice and this was one of the things that came out of alllllll of that work.

I really appreciate your thinking on this. And I especially appreciate how SPECIFIC and well-researched this entire piece was. I am bookmarking it and will for sure return to it several more times.

"My image of an artist in motion is one of the brows furrowed in concentration, lips pursed in judgement, and eyes anything but closed in the way it does during a smile. It is fully open, absorbing the world in front of it." (from an old piece)

Dissatisfaction is the gap between your desired state and your current state. Buddhists say: let go your desires, and you will be satisfied. But while it's meaningful to drop your desires, the struggle towards your wants is where meaning is created.

I really like this definition of the divine discontent, and think it can be also be a way to distinguish between desires that are worth letting go of and desires worth the discontent for.