the allure of the literary ranked list

23 brief reviews of books on the NYT's "100 Best Books of the 21st Century" list

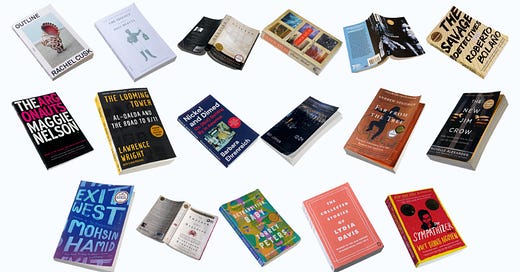

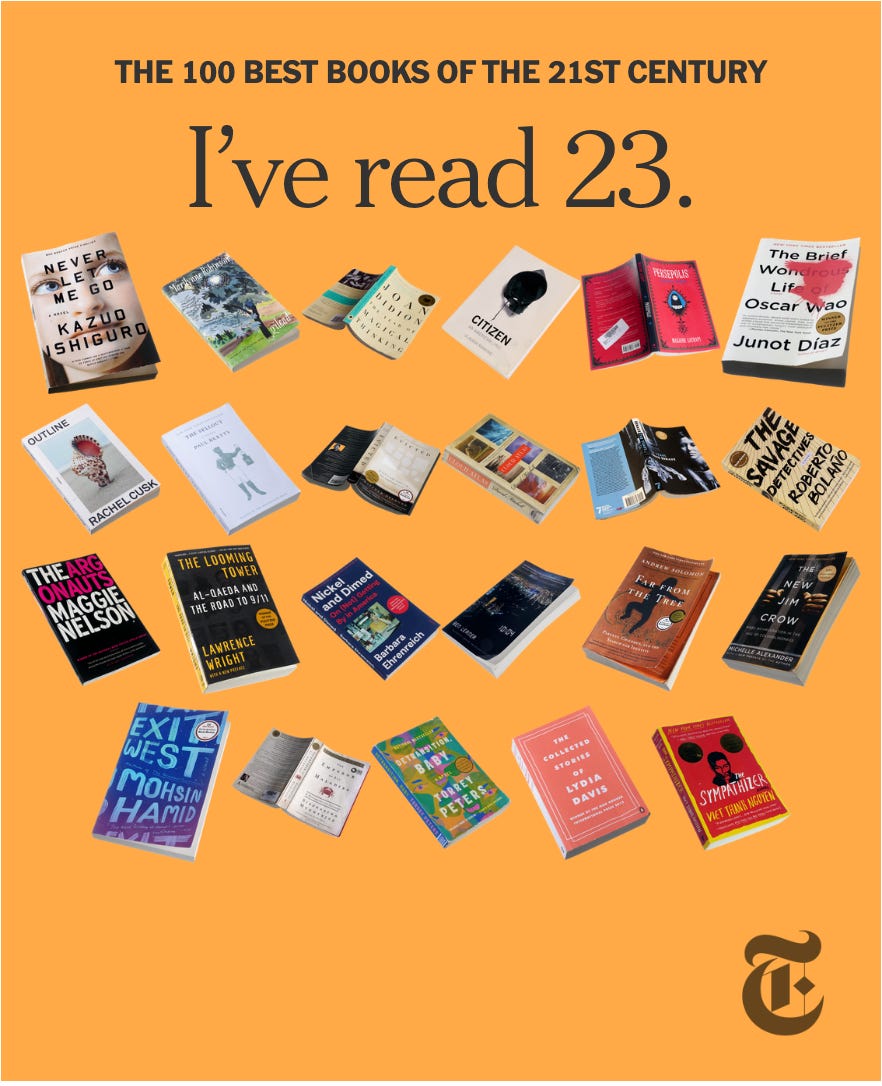

Like everyone else “into literature” and possessing an internet connection in the last week, I’ve been deeply invested in the New York Times’s “100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” I’ve read 23 of them and included brief reviews of each below—some books are overrated, some correctly rated—but first, some takes on the list itself.

Ranked lists are inherently fascinating to people—as is the highly contested nature of what’s “best” in literature. And the choice to slowly roll out the list—20 books at a time—built anticipation and interest. As

noted, creating the list is not an act of literary criticism, it’s an act of content creation. The Times has “invented a fantasy football bracket for the people who are normally left out of fantasy football due to their total ignorance of football.”To create the list, the NYT asked 503 writers and critics for their top 10 books, with additional input from their own staff. Some of the writers involved revealed their ballots (more content to consume!). I loved Karl Ove Knausgaard and Anand Giridharadas’s picks—both nominated Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, which ended up on the final list!—and found Ryan Holiday’s picks remarkably…bad? Imprecise? (Cal Newport’s Deep Work as one of the 100 best books of the 21st century??) I was also surprised and delighted to see Stephen King nominate Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, which didn’t make the list but is one of my favorite speculative fiction novels about climate change and dystopia.

Of course, there are surprising inclusions and staggering omissions:

The list is very Anglocentric: Only 13 of the novels are translated from other languages, and of those, 3 are Elena Ferrante novels, and 2 by Nobel laureates (easy nominations to make, frankly). There are no Knausgaard books! Were the votes simply split between the 6 books of his autobiographical My Struggle series?

The list also excludes Sally Rooney, who I see as very characteristic of certain trends in 21st century literary culture, and one of the most influential novelists working today. (She’s also an underrated essayist—her op-ed for the Irish Times about Ireland’s relationship with the US during the Gaza genocide is brilliant, as is her op-ed about renters’ rights.) I’m guessing that the 503 writers surveyed are on the older side and not reading her—or that any votes for Rooney books were split between her 4 novels?

The list has a lot of repeats: 3 Jesmyn Ward novels, 2 Zadie Smith novels, 3 George Saunders short story collections. Not to mention the 3 Ferrante novels. It’s strange to see multiple works included from older literary luminaries, and hardly anything from younger writers. As

noted in his post on the NYT’s list, “This is a list of boomer authors, largely.” (He also brings up Hanif Abdurraqib as a surprising omission—I agree completely!)There’s barely any poetry: There’s only one work, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. A more poetry-forward list would probably include Anne Carson or Louise Glück.

The political books are all very liberal-centrist picks: I really, really do think that David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years should be on here, as it’s such a masterfully readable and expansive history of debt and credit in human culture, and how these concepts shape economic inequality and morality today.

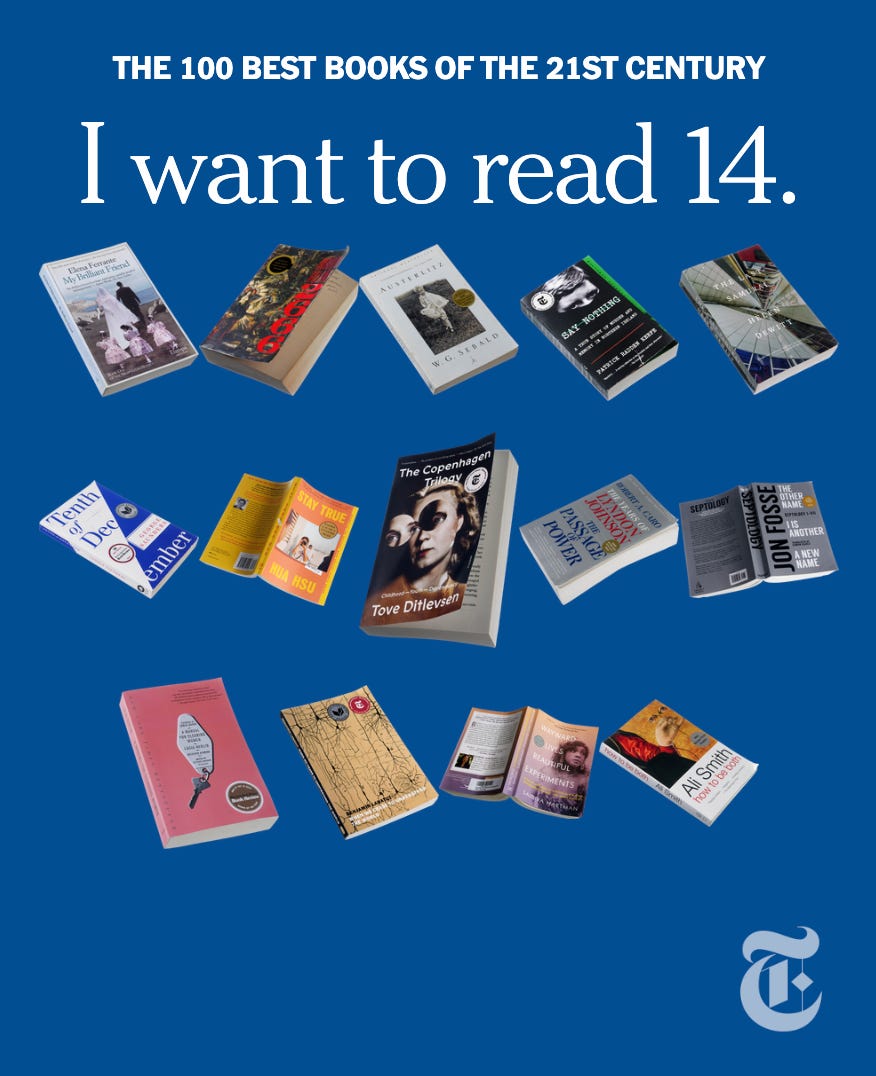

But now that I’ve aired my complaints about what’s not on the list—here’s how I felt about what made it in. Below, 23 brief reviews of the books I’ve read, and some reflections on the 14 books I feel exceptionally guilty about not having read yet!

The 23 books I’ve read

#9: Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go (2005). Ishiguro excels in having a great concept for a novel and decent characters. I don’t think his sentence-level style is exceptionally beautiful, so he’s never been one of my favorite writers. But I like him! Never Let Me Go is a lovely novel in the British-boarding-school-bildungsroman genre, about young students falling in love and making art and speculating about their future—a future with an excellent sci-fi twist to lend the novel some pathos and ethical anxiety that lingers after you read it.

#10: Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead (2004) is an extraordinary epistolary novel about an elderly pastor writing to his young son about his life, ethical principles, and anxieties about death. Robinson is surely one of the most sublimely contemplative writers of our time, and the protagonist’s voice is so generous, patient, and reflective. I cannot recommend this enough! It might be the best novel I’ve read about fatherhood and parenting. I also really adore how Robinson writes about ethical and spiritual commitments—you don’t even have to be Christian to enjoy her style, imo! I’m certainly not.

P.S. If you’re a Robinson devotee,

regularly writes about her on his newsletter .#11: Junot Díaz’s novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007). I read this nearly a decade ago (it feels so surreal to write that!), when I was interning at an arts tech startup in NYC for the summer and obsessed with this app called Oyster, which was meant to be a beautifully designed “Netflix for books.” Before the app shut down (it turns out Netflix’s business model didn’t translate to literature) I read a lot of really great books for $9.99/mo on my phone, including 2 or 3 books by Junot Díaz.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is a multigenerational immigrant novel, which normally I hate—but Díaz has such a remarkably engrossing writing style that makes liberal use of colloquialisms and youthful irreverence and Spanglish, so it’s a pleasure to read. The protagonist is a young kid who feels unattractive to the opposite gender but is desperate to fall in love. There’s some complicated family history. There are footnotes that elaborate on the story in a delightfully metafiction-y way. It’s good!

#12: Joan Didion’s memoir The Year of Magical Thinking (2005). I tend to associate Didion with her essay collections—Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album—but both were published in the 20th century, whereas the newer The Year of Magical Thinking qualifies for the NYT’s list. It’s a memoir about the year following Didion’s husband’s unexpected death, and how she—in her trademark detached, journalistic style—attempts to grapple with the ebb and flow of her grief.

The memoir opens with the following brief, staccato lines:

Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends. The question of self-pity.

Didion’s distaste for self-pity is obvious in her other writing. As Deborah Nelson wrote in Tough Enough (one of the best books I read in 2023):

Self-pity and self-delusion are the moral flaws that underwrite bad politics and bad writing, which for Didion are one and the same thing. Since she began to develop an aesthetic philosophy in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Didion has advocated “moral toughness” as the antidote to the social and political turmoil of the late twentieth century.

But how do you avoid self-pity when it’s about the disorienting death of someone you love? I find The Year of Magical Thinking particularly touching because Didion is constantly, agonizingly, trying to navigate the tension between impossible grief and her own literary and aesthetic commitments.

#14: Rachel Cusk’s novel Outline (2015). I really do think of Outline as one of the most artistically innovative novels I’ve ever read—it’s autofiction, supposedly, but where the Cusk-like narrator is a rigorously unrevealing “cipher who inspires other people to confess,” as Heidi Julavits said of the novel. Every other character in the novel immediately offers up their entire life story (all the successes, all the shameful secrets) as soon as they meet the narrator. Cusk’s writing makes this all seem so natural, so inevitable—but that really isn’t how life works! People don’t always tell you about their love affairs and their divorces so easily! And it’s strange to have a novel that feels so populated by other people’s stories, while the protagonist remains mysterious. But Cusk makes this all seem very, very ordinary—it’s really a remarkable stylistic achievement.

P.S. If you’re interested in Cusk, this New Yorker profile of her is a fascinating look at her literary career, her marriages, and her family life. Also, a bit of a medium-hot take…while I love Cusk, I’m always surprised at the popularity of Outline, which is a very good but somewhat aloof read. I really don’t think it would have become so popular without the Instagrammable cover design!

#17: Paul Beatty’s novel The Sellout (2015). I read this in 2016, in the run-up to Trump’s election. It remains one of the most brilliant and brutally funny satires I’d ever read. The novel follows a Black man in a small, agrarian town outside of Los Angeles who provocatively leans into certain racial stereotypes, pushed to the point of absurdity: he grows artisanal watermelons and tries to resegregate his local bus and public school system. It’s hard to describe the plot (especially since I read it a very long time ago)…but what I remember is Beatty’s mischievous use of taboo topics to point out how America remains, at the end of the day, not very post-racial at all.

#21: Matthew Desmond’s nonfiction book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016). A brilliant sociological work that follows 8 families in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to show how the 2008 financial crisis affected people, especially poor families struggling to find affordable housing. These case studies allow Desmond to clearly convey the broader issues around urban gentrification, housing affordability, economic exploitation, and tenants’ rights in the US.

A key part of Desmond’s argument is that lack of affordable housing doesn’t just happen. The poor do not just happen to be poor—they are poor through circumstances or structural inequalities, and they are kept poor through systems that continually marginalize and constrain them:

When I began studying poverty as a graduate student, I learned that most accounts…were writing about poor people as if they were cut off from the rest of society…The poor were being left out of the inequality debate, as if we believed the livelihoods of the rich and the middle class were intertwined but those of the poor and everyone else were not. Where were the rich people who wielded enormous influence over the lives of low-income families and their communities—who were rich precisely because they did so? Why, I wondered, have we documented how the poor make ends meet without asking why their bills are so high or where their money is flowing?

In 2017, I spent a week of vacation reading this and Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (discussed below). These books demystified poverty for me, and they helped me see how the phenomenon of a single mother evicted from an apartment, or a young man incarcerated for twenty years, was not just an individual story but a story about a system, a system of ongoing injustice and cruelty. In this system, the rich aren’t rich by mistake; they are rich because we divert resources to them, and withhold them from others:

Each year, we spend three times what a universal housing voucher program is estimated to cost (in total) on homeowner benefits, like the mortgage-interest deduction and the capital-gains exclusion. Most federal housing subsidies benefit families with six-figure incomes. If we are going to spend the bulk of our public dollars on the affluent—at least when it comes to housing—we should own up to that decision and stop repeating the politicians’ canard about one of the richest countries on the planet being unable to afford doing more. If poverty persists in America, it is not for lack of resources.

P.S. If you’re interested in eviction and tenants rights, I return often to the writer and organizer Tracy Rosenthal’s “101 Notes on the LA Tenants Union”—which also reoriented my understanding of how to think about housing:

First of all, there is no housing crisis.

Housing is not in crisis.

Housing needs no trauma counselors.

Housing needs no lawyers. Housing needs no comrades or friends. Housing needs no representatives. Housing needs no organizers.

When we call this crisis a housing crisis, it benefits the people who design housing, who build housing, who profit from housing, not the people who live in it.

It encourages us to think in abstractions, in numbers, in interchangeable “units,” and not about people, or about power.

We don’t have a housing crisis. We have a tenants’ rights crisis.

#28 is David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2004). I have to be completely honest: I remember nothing at all about this novel, except that it was sort of sci-fi/speculative-ish, and there were multiple characters in different places and times, and they were subtly interconnected somehow. Incredibly overrated as a novel.

#34: Claudia Rankine’s poetry book Citizen: An American Lyric (2014). I’m realizing now that Rankine was my way back into reading poetry—I read Citizen in fall 2020, at a time when I exclusively read nonfiction because it felt “serious” and “useful.” Rankine’s book-length poem, which masterfully employs an almost prose-like, essayistic way of discussing race in America, was a useful bridge between my nonfiction-only era and the way I read today—where I’m able to see poetry and fiction as similarly serious and useful, capable of conveying information about issues like race and poverty in an unexpected way.

#37: Annie Ernaux’s The Years, translated from French by Alison L. Strayer (published in English in 2018). I could go on and on about this book, which I think is formally and stylistically and politically one of the greatest works I’ve ever read—reading it was such an activating experience. It’s written as a collective autobiography, with Ernaux narrating her post-WWII childhood and all the political and cultural events that followed—the Algerian war for independence; the French general strikes of May 1968; the election of Mitterand, France’s first left-wing politician. She does this through the pronoun nous in French—first person plural, or we in the English translation—which has the extraordinary effect of making the story not just about Ernaux’s life, but about French life in general in this time. Her writing moves beautifully between specific images of everyday life (coveting beautiful garments at a department store, for example) and broader political concerns.

Ernaux, of course, won the Nobel Prize in literature in 2022. If you haven’t read any Ernaux yet, I personally think The Years is her best work and worth reading first! But A Man’s Place (about her working-class father and his class anxieties) or Happening (about Ernaux seeking out an abortion before it was legalized in France) might be more typical of her style.

#38 Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, translated by Natasha Wimmer f(?/2007). I have this strange tendency to read the “minor” work of a great writer first, before getting to the one they’re really known for. With Nabokov, for example, I read Despair first (which no one seems to talk about!), then Pale Fire (because it was quoted in the film Blade Runner 2049), and only then did I get around to his most well-known work: Lolita. Similarly, when I decided I really had to read Bolaño, I started off with The Savage Detectives (#38) instead of his celebrated 2666.

The Savage Detectives is (initially) about a seventeen-year-old boy who befriends a group of poets that are trying to create a new movement, which they call Visceral Realism. The boy is captivated and entranced by the strange leaders of this poetic movement, and the book eventually incorporates more characters who have all, somehow, been drawn into the orbit of Visceral Realism and have both literary and interpersonal connections to the poets involved. There’s a lot of romantic gossip and starving poets shoplifting books—and grazing mentions of the Chilean coup where the democratically-elected president Allende was overthrown by the military, and the Mexican student movement of 1968…

So it’s a novel about the little internecine dramas of literature, but it’s also about how literature can’t help but be implicated in national and international politics. I really love Bolaño’s voice; he’s always funny and sharp and darting off in strange directions, and The Savage Detectives reads like a book that is 90% digressions, but enjoyably so. I never know where his writing is going. And it’s better that way.

#45: Maggie Nelson’s memoir The Argonauts (2015). The greatest contemporary love story and family story. Maggie Nelson is surely one of the most influential writers working today—with her much-imitated synthesis of memoir, criticism, and theory. The Argonauts is a moving depiction of Nelson’s marriage to the trans artist Harry Dodge and her pregnancy, as they figure out what a queer family and domestic life might look like.

It’s a queer love story, but it’s not exclusively for the queers. You know how there’s a particular subset of straight Gen Z guys who are all reading bell hooks’s All About Love right now? And finding elaborate ways to mention this to women they’re trying to hit on? Those guys would love Maggie Nelson…

#48:Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2003). In high school I was very impressed and intimidated by a woman who I’d met at the California State Summer School for the Arts (CSSSA)—a publicly funded arts program established in the ‘80s to give high school students a rigorous, pre-professional education in the visual, literary, or performing arts. Writing this now, I’m struck by how many of my CSSSA peers were genuinely from working-class or lower middle class backgrounds—that’s what meaningful funding for the arts looks like, and it affects whether the art and literature we experience is made by working-class people as well, or if it’s only made by the wealthy…

But anyways! This CSSSA peer of mine was quite invested in—not comic books, but graphic novels—as a serious medium of artistic expression. She introduced me to Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, an autobiographical novel about Satrapi’s childhood in Iran during a politically potent and chaotic era: the end of the Shah’s rule, the Islamic revolution, and the political activism that Satrapi (and her family and friends) were involved in. It’s beautifully drawn, charming, moving, tragic, hopeful…highly recommend!

#55: Lawrence Wright’s nonfiction book The Looming Tower (2006). A decently engrossing history of al-Qaeda, 9/11, and America’s intelligence bureaucracy. Wright’s book uses an intimate biographical approach to dramatize these larger topics—to explain al-Qaeda, for example, Wright gives us the life stories of Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahari (who succeeded bin Laden as the leader of al-Qaeda). One takeaway from Al-Zawahiri’s story…for political prisoners, it seems like being imprisoned can be a radicalizing experience, and a way to network with others. Al-Zawahiri was one of hundreds of people arrested after Egyptian president Anwar Sadat was assassinated (although I don’t believe he was directly part of the plot?). He was tortured severely in prison, but also emerged as a recognized minor leader and more ideologically committed to Salafi jihadism.

I don’t know if this would be a top 100 book for me, though! If I had to pick a book in the political-history-about-America-and-its-foreign-affairs category, I’d probably nominate Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (2008). I read this in the run-up to the 2016 American presidential elections, and to me it is the book for understanding the longer history of political polarization in America. I have inflicted this recommendation on basically all of my friends…and now I am inflicting it onto you.

#57: Barbara Ehrenreich’s book of investigative journalism, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (2001). Read this a few years ago. It chronicles the fallout of a 1996 welfare reform bill that was part of President Bill Clinton’s project to “end welfare as we know it.” The bill assumed that many people benefitting from welfare were simply lazy, and that the government needed to encourage more “personal responsibility” among recipients.

To understand whether the working poor could get by without welfare assistance (and cover all their expenses with minimum-wage labor), Ehrenreich went undercover and worked several menial jobs, including as a hotel maid, Wal-Mart employee, and waitress. Her conclusion? Working conditions are abysmal; “unskilled” jobs require a great deal of skill; and the poor frequently encounter unfair and arbitrary additional costs:

There are no secret economies that nourish the poor; on the contrary, there are a host of special costs. If you can’t put up the two months’ rent you need to secure an apartment, you end up paying through the nose for a room by the week.

One critique I’ve seen about Ehrenreich’s book is that there is something cruel and disrespectful about it—a middle-class journalist and academic LARPing as one of the poor. Of course, in an ideal world the poor would be able to testify to their own conditions, and be believed. But in the world we do have, I think it was actually quite influential for someone like Ehrenreich—who was assumed to be more methodical, reliable, and systematic—to convey how deeply unfair it is to be poor in America:

When someone works for less pay than she can live on—when, for example, she goes hungry so that you can eat more cheaply and conveniently—then she has made a great sacrifice for you, she has made you a gift of some part of her abilities, her health, and her life. The “working poor,” as they are approvingly termed, are in fact the major philanthropists of our society. They neglect their own children so that the children of others will be cared for; they live in substandard housing so that other homes will be shiny and perfect; they endure privation so that inflation will be low and stock prices high. To be a member of the working poor is to be an anonymous donor, a nameless benefactor, to everyone else.

#62: Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04 (2014). A key text if you’re interested in American autofiction, fiction about the art world, and really good fiction by someone who started off as a poet. (It seems like poets are always becoming gifted novelists, but novelists never become gifted poets…why is that? I have my own theories but I’m interested in yours!) The novel is set in NYC and is about Lerner trying to write a book (which ends up being 10:04). It’s a conceit that could feel quite navelgazing if not for Lerner’s brilliant style—his writing is so conceptually and stylistically rich, and each sentence is just an invigorating experience to read.

#67: Andrew Solomon’s Far From the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity (2012). A very, very long book (over 900 pages! I spent weeks patiently working through it) about how parents relate to children who might be very different from them. The differences Solomon examines are tremendously varied: D/deafness, schizophrenia, criminality, genius, and more. It’s a beautiful book about the terrors and pleasures of parenting, of not knowing who your kid will become. The conclusion, btw, is quite sweet—Solomon is gay, and he writes about coming out to his parents, marrying his husband, and the unusual (but very beautiful) family life they’ve built together. From a Guardian interview:

My now husband is the biological father of two children with some lesbian friends in Minneapolis, and he had already had one of them at the time I was working on the book. I have a daughter with a friend from university and they live in Texas. And then my husband and I decided that we wanted to have a child together, and we now have a son, George, who is here with us now at this very moment, running in and out of the room. He'll be four in April. It's five parents and four children in three states.

#69: Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010). This and Matthew Desmond’s Evicted (#21, discussed above) might be the most “essential” books I’ve read on poverty and race in America. Alexander describes how, in a supposedly “colorblind” age with visible forms of “black exceptionalism”—such as Barack Obama’s election as president—we are nevertheless living in a society in which Black men are disproportionately incarcerated, labeled as felons, and cut out of society and most forms of social mobility for the rest of their lives. Much of this can be attributed to disastrous choices made during the war on drugs. “[T]he United States,” Alexander writes, “now boasts an incarceration rate that is six to ten times greater than that of other industrialized nations…and no other country in the world incarcerates such an astonishing percentage of its racial or ethnic minorities.” This is higher than the incarceration rate of “highly repressive regimes like Russia, China, and Iran.”

In the era of colorblindness, it is no longer socially permissible to use race, explicitly, as a justification for discrimination, exclusion, and social contempt. So we don’t. Rather than rely on race, we use our criminal justice system to label people of color “criminals” and then engage in all the practices we supposedly left behind. Today it is perfectly legal to discriminate against criminals in nearly all the ways that it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans. Once you’re labeled a felon, the old forms of discrimination—employment discrimination, housing discrimination, denial of the right to vote, denial of educational opportunity, denial of food stamps and other public benefits, and exclusion from jury service—are suddenly legal. As a criminal, you have scarcely more rights, and arguably less respect, than a black man living in Alabama at the height of Jim Crow. We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.

#75: Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (2017), a speculative fiction novel about a young refugee couple that flees their unnamed country through a series of magical doors to other cities: Mykonos, London, and then Marin in California. It’s very clearly a commentary on migration and the European refugee crisis—the unnamed home country feels like a stand-in for many Middle Eastern countries, and the device of the doors—which bring the couple from country to country—allow Hamid to comment on undocumented immigration, asylum policies, and xenophobia in wealthy Western countries.

Brilliant concept, mediocre prose (in my opinion…I just didn’t enjoy reading it that much.) I’m consistently surprised by how much praise this book gets. But you can judge for yourself—here’s an excerpt from the beginning of the novel, and another that shows the couple migrating through one of the magical doors.

#84: Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Emperor of All Maladies (2010) A really remarkable work of nonfiction writing about cancer, from when it was first discovered and documented (by the Egyptian physician Imhotep in 27th century BCE) to our contemporary attempts to better diagnose and address it. I read this ages ago—what sticks out in my memory is:

How earnestly people believed, in the 20th century, that we were only a few years away from an effective cancer treatment that would work for all types

How early cancer treatment research relied on some of the same toxins and substances that were also used as chemical warfare agents during WWI and other conflicts—like nitrogen mustard/mustard gas. It seems like every scientific, medical, or computing project of 20th century America ends up connected to defense research…

#87: Torrey Peters’s novel Detransition, Baby (2021). It was surprising to see this on the list! I love Peters’s novel; I think it’s so funny and sincere and irreverent. I’m not sure if I would put it on my list of 100 best books, but I encourage everyone to read it, for its sharp and hilarious sendups of LGBTQ culture:

She had a funny-’cause-it’s-true joke that she liked to ask whenever she met a new trans girl. So which of the three transsexual jobs do you do? Computer programmer, aesthetician, or prostitute? Reese always hoped the answer would be prostitute, because prostitutes were the ones with a good sense of humor.

This is very me:

she always complimented bowl cuts, because she’d made enthusiastic appreciation of queer style an important part of her social approach, regardless of her actual opinions.

Peter’ss novel is about a complicated romantic/domestic ménage a trois (a trans woman, a detransitioned trans woman who is still uncertain about whether life as a man again can work out, and a cis woman who is deciding whether or not to have a child). And what I love about it is that Peters recognizes how an unassailable, sharp criticality—that trains itself on cis/straight culture as well as the absurdities of LGBTQ culture—can coexist with a very moving exploration of trauma, sexuality, and gender.

And without legible traumas to point to, what would pain make her? At best, a trans version of those Didion-worshipping bourgeois white girls who subscribed to a Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain, those minor-wound-dwelling brooders with no particular difficulties but for an inchoate sense of their own wronged-ness, a wronged-ness that fell apart when put into words but nonetheless justified all manner of petulance and self-pity.

#88: Lydia Davis’s The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (2010), an anthology of 4 other Lydia Davis collections (including the one I mentioned in my Atlantic article about 6 great short story collections). I am so happy to see her on this list! I am a true Lydia Davis devotee: she’s the reason I read Proust, and the reason I fell in love with French literature and then with European literature in translation more broadly. She seems to have this indefatigable, endless capacity to experiment with each story—and I truly think her insights into human nature are unparalleled. If you want a preview, “Break it Down” is one of my favorites. But it’s a more conventional length—to really understand Davis, you need to read some of her very short flash fiction stories. Conjunctions has published 5 of them here.

#90: Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer (2015). I love this novel and honestly think it should be higher on the list. Nguyen has so capably synthesized stylistic approaches from great American literature (the novel is very inspired by Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man) and academic approaches to race, decolonization, representation, etc into a really engaging story. The protagonist is a double agent who pretends to be a loyal agent for the American-supported south Vietnamese government, while covertly committed to the Communist cause. After fleeing Vietnam during the fall of Saigon, he ends up in southern California, quietly negotiating his political commitments alongside his growing fascination with American culture. It’s also so funny!!! To me, this and The Sellout are the great American novels of the last 24 years.

What I haven’t read

I tend to think that people are defined not just by the books they have read, but the books they want to read—the books they speak of with some measure of guilt, premature affection, or longing. So here’s my to-read list:

#1: Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, translated by Ann Goldstein (published in English in 2012). I’m a bit embarrassed that I haven’t read this yet! It’s because everyone I know who’s read Ferrante read her years ago, and it feels as if I’ve missed the moment. Maybe her position in the NYT’s list will create a new moment, with new Ferrante readers, that I can join?

In any case, I really do think that women’s fiction and television in the last 2 decades has been defined by the theme of “complicated friendships”—that strange and potent confluence of admiration, envy, and rivalry. Examples include Zadie Smith’s Swing Time, Lena Dunham’s Girls, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. But Ferrante’s approach might turn out to be the most influential and emblematic of that genre.

#6: Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666, translated by Natasha Wimmer (published in English in 2008). I feel like a fraud admitting that I haven’t read this—even though I claim to be so invested in literary fiction in translation! I did start reading it—when my girlfriend and I were visiting CDMX in December and waiting in line at the Museo Jumex for something—maybe I didn’t continue because it’s such an imposing novel to read on a tiny iPhone screen.

#8: W.G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, translated by Anthea Bell (published in English in 2001). Yet another canonical work of European literature in translation which marks me out as a FRAUD for not having read! People love this Sebald guy! Whenever someone brings him up, I end up feeling very embarrassed and I change the topic to some other European writer who also wrote about post-WWII Europe, like Thomas Bernhard…

#19: Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland (2019), which is about the Troubles. When I first moved to London in 2019, people kept on referencing “the Troubles” in a way that made me feel keenly ignorant of the world beyond American politics. (I felt similarly embarrassed to not really understand the significance of “partition,” as in Britain’s partition of India and Pakistan, and the horrifying violence, displacement, and deaths that followed.) It seemed as if you really couldn’t be a politically conscious resident of the UK without understanding three things: the Troubles, British imperialism in India, and the British slave trade in the West Indies.

Anyways, I know a little bit more about partition now, but I still feel exceptionally under-informed on the history of the Troubles and their impact on Ireland. I really do need to read this…

#29: Helen DeWitt’s novel The Last Samurai (2000). I have somehow never gotten around to this, even though I loved her short story collection Some Trick, and I am constantly recommending DeWitt’s infrequently-updated blog to people (especially her post on learning French via reading Proust).

#54: George Saunders’s short story collection Tenth of December (2013). Despite my profound appreciation for George Saunders as a short story writer and teacher (his book A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, as well as his Substack

, are both profoundly useful for learning to read and write fiction)…I haven’t finished a collection of his!#58: Hua Hsu’s memoir Stay True (2022). The only explanation I have for not reading this is that when there is an “important,” “searing,” “urgent,” “remarkable” work by an Asian-American writer, I get stressed and convince myself that I have to read it at exactly the right time in my life, where I will be able to get the greatest emotional and literary value from reading it. It is unclear what the right time means, however. The right time to read Hua Hsu has apparently not showed up yet, nor has it showed up for Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings or Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart.

#71: Tove Ditlevsen’s The Copenhagen Trilogy, translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman (published in English in 2021). I’m pretty sure Ditlevson has been on my mind lately because I revere the Danish writer Olga Ravn’s fiction, and Ravn edited a volume of lesser-known writing by Tove Ditlevson.

#73: Robert Caro’s The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson (2012). Robert Caro is one of the greatest chroniclers of 20th century American political history (the other is Rick Perlstein, in my opinion)…but he writes such big books! I’ve read Caro’s memoir/essay collection Working, where he describes his research and writing process, and it was an enormous inspiration. But I read it because it was short. I don’t know if I’ll ever get around to Caro’s great biography of Robert Moses, nor his still-unfinished biographical epic on Lyndon Johnson (The Passage of Power is the 4th in the series)…there’s simply too much to read, and if I had to prioritize a big series, I’d rather read:

#78: Jon Fosse’s Septology, translated by Damion Searls (published in English in 2022). Also haven’t gotten around to this, because the year Septology was published in English was also the year I committed myself to reading Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. There are only so many 6-to-7-volume literary masterpieces that you can commit to at once! But I love Fosse; his book Melancholy was one of my favorite books I read in 2023, for its portrayal of “the artistic impulse, mental derangement (and familial histories of mental health disorders), the agony of institutionalization, the disorientation of grief.” I’m quoting my older post because I’m lazy…

#79: Lucia Berlin’s short story collection A Manual for Cleaning Women (2015). All of my favorite people like Lucia Berlin: my friends Ari and Hua, and of course my queen Lydia Davis, who says:

Lucia Berlin’s stories are electric; they buzz and crackle as the live wires touch. And in response, the reader’s mind, too, beguiled, enraptured, comes alive, all synapses firing. This is the way we like to be when we’re reading—using our brains, feeling our hearts beat.

#83: Benjamin Labataut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, translated by Adrian Nathan West (2021). I’m absolutely certain I would like this; I love it when people write about great thinkers and theorists and scientists and artists in vividly stylish ways. Quite a few friends who I respect enormously have read this and liked it. I just…you know…there’s always so much to read…

#96: Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019). Hartman’s book feels like one of the most influential contemporary examples of blending history and fiction, scholarly research (Hartman is a professor of African-American literature at Columbia) and literary experimentation. I am convinced I will “get to this” “someday”, as these are all things I’m very interested in!

#99: Ali Smith’s novel How to Be Both (2014). I really revere Ali Smith. Her seasonal quartet of novels (titled Autumn, Winter, Spring, and Summer) are incredible to me—she writes beautifully about how art moves someone and shapes someone’s life, and how issues like Brexit and climate change and migration might creep into ordinary life. But I’ve never managed to read How to Be Both. I’ve probably checked it out from the library 5 times in the last 5 years and then returned it unread. For no particular reason!

And that’s all I have to say about the NYT’s 100 best books! Thank you for being here—reading, scrolling, etc. And I’d love to hear your thoughts on books that you think are OVERRATED, UNDERRATED, CORRECTLY RATED, and UNFAIRLY EXCLUDED from the list!

I was surprised to have read thirty two of the books. None, except perhaps the Ernaux book were in my top xx. Those would have included Flights by Olga T, the Details by Ia Genberg, The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gundy, a book I suspect I may not like as much now as I did when I first read it but which I love so much when I first read it, I gotta put it on my list, Checkout Nineteen, a marvelous book about much including reading itself, by Claire Louise Bennet, last year's Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, the Topeka School by Ben Lerner, and an Immense World, by Ed Yong, a book about how other creatures sense and cognize that makes the reader feel a part of something so much larger than themselves.

I agree with every single omission you have pointed out - the lack of translated books while unsurprising, was still shocking. What I also thought is so may of the books are american centric in topic! While an element of this is to be expected as it is the NYT, all of the non fic (bar the troubles book) and memoir is about American events/culture and society. As a reader from the UK I just really noticed this, I hardly recognised many of the books and I can't help but wonder if this is because they are so American orientated in nature? I think the list is reading like a reflection of a certain age demographic of Americans and the books that have been available to them in their lifetime - I think it reflects super interesting trends in publishing in America and how this dominates what is available to be read/purchased/consumed in the country - perhaps a tell that publishing houses in the US deem books about the US the most 'important' - (this is an unrefined thought but one I have really been thinking about since the list)

Rooney one of THE 21st century writers - I think her exclusion might be related to the age of the voters asked? No Rooney, Olga Tokarczuk, Yaa Gyasi, S A Cosby, Douglas Stuart or Alejandro Zambra is shocking to me. I also think having no trans Japanese lit on there is absolute insanity.

While good I agree that Never Let Me Go and Exist West don't feel worthy of that list! I have only read one Ferrante novel (days of abandonment) but was shocked to see her as no1! I am going to have to read it out of curiosity, but I didn't think DOA deserved a place on that list. The only books I have read that I did think deserved a place were 'Demon Copperhead' and 'Station Eleven' because they were very very good.