take the paranoid reading pill

how to write about conspiracy theories ✦ and the process of revising an essay

My latest essay, “Feelings Over Facts: Conspiracy Theories and the Internet Novel,” was published Friday at the Cleveland Review of Books. It’s about the power of conspiracy theories in a post-Trump, post-Covid era; how calling something a “conspiracy theory” is often a way to dismiss a legitimate critique of power; and what it means to empathetically engage with the fears behind a conspiracy theory.

More concretely, it’s an essay where I review 2 nonfiction books published last year: the British art historian Larne Abse Gogarty’s What We Do Is Secret and the Canadian activist Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. I then use their ideas to analyze 3 novels: Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill (2019), Tao Lin’s Leave Society (2021), and Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts (2021). This is, admittedly, an unusual set of books to pair together—but they depict, in various ways, what it looks like to obsessively research and discuss conspiracy theories on the internet.

When I first started working on the piece, I was worried that I was too late—these are all books that came out from 2019–2023, and it’s not exactly timely to publish a review in June 2024! But the ideas in the essay remain relevant, I think, because political discourse has been indelibly shaped by the Trump and COVID years. I’m particularly interested in how incoherent public health messaging and anti-vaccine anxiety—and the ineffectual pleas to simply “trust the science”—made many people distrustful of their existing political leaders and institutions. That distrust has stayed, and is key to the rise of far-right political parties in the US, Canada, UK, and Europe. What was politically unimaginable a few years ago is now normal. In the recent EU parliamentary election results, far-right populist parties like National Rally in France, Brothers of Italy, and AfD in Germany all saw enormous gains. To understand these changes, we need to understand how conspiracy theories are destabilizing existing right/left labels and creating new political alignments.

All that to say: please read my essay! (And let me know what you think about it!) But in this Substack post, I’d like to write a bit about the process of writing the essay. I’m endlessly fascinated by the concrete details of how people actually work—I want to know how chefs develop recipes, how architects sketch buildings, how gardeners choose plants for a particular site. I want someone to unfold their process in front of me, so that I can draw out lessons for my own work.

Below, I’ll discuss: Where the essay idea came from, the pitching and researching and writing process, and a little website I made to visualize my revision process.

The idea

Last November, I was visiting NYC and my girlfriend (who somehow manages to hear about all the interesting events! including in cities she doesn’t even live in!) sent me an Instagram post about an event for Larne Abse Gogarty’s book, What We Do Is Secret: Contemporary Art and the Antinomies of Conspiracy.

I was free that Saturday afternoon. I like reading art history, theory, and criticism (yet another example of research as a leisure activity) even though I really don’t know much about it. And the description of the book said that it discussed “post-internet art.” I bought a copy so I could read it before the event.

Gogarty’s book ended up being very intellectually rich and exciting, and I was particularly intrigued by 2 arguments she makes:

First, that conspiratorial thinking, and conspiratorial aesthetics, appear in both right-wing and left-wing art. It’s a pejorative term, Gogarty notes: by calling something a conspiracy theory, you are situating it as beneath serious consideration. That doesn’t mean we should rehabilitate all conspiracy theories—some are genuinely insidious, and easily weaponized against marginalized populations. But other conspiracy theories are worth taking seriously, since they reflect how power is subjectively experienced by people, and are useful for understanding all the anxieties, fears, insecurities, and traumas that the powerless experience.

Second, that there’s an approach to highly political art—what she calls “legibly political art,” which clearly establishes its ideological convictions through mapping out abuses of power—that is aesthetically facile and just…boring. It explains too much; it proselytizes to the viewer, instead of allowing the viewer to participate in the work. This work is critically acclaimed, Gogarty suggests, because we assume that informative art is politically useful art. What if that’s not the case? Why do we believe that simply presenting information about some systemic evil is enough to solve it?

The second argument made me think of the literary scholar Eve Kokofsky Sedgwick’s iconic essay “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You.” I first read it during grad school, when I noticed a particularly frustrating tendency in some of my seminars. I would sometimes observe, in class discussions, an overwhelming group instinct to find what was inadequate, limited, unsatisfactory, and even problematic about some work. To be clear, there are works which are inadequate and problematic, and their limitations deserve to be discussed! But I kept on wondering why this had become the primary, and sometimes only, way we could process a text. Why were we so relentlessly consumed with finding a text’s failures? Why couldn’t we read it more generously, to understand what it was trying to do and what it might offer us?

Sedgwick’s essay is all about that—the instinct towards “paranoid reading” because it seems more politically progressive and useful. The essay has a very useful analysis about why that paranoia exists, and one particular observation is very applicable to Gogarty’s critique of “legibly political art.” Paranoia, Sedgwick notes, “places its faith in exposure,” and

acts as though its work would be accomplished if only it could finally, this time, somehow get its story truly known. That a fully initiated listener could still remain indifferent or inimical, or might have no help to offer, is hardly treated as a possibility.

So I was thinking about Gogarty in relation to Sedgwick—especially since both writers stress the storytelling involved in paranoia. Which reminded me of a Bookforum article from 2021, where 13 different writers were asked “What forms of art, activism, and literature can speak authentically today?” I was particularly moved by Ottessa Moshfegh’s response:

I wish that future novelists would reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society. Art is not media. A novel is not an “afternoon special” or fodder for the Twittersphere or material for journalists to make neat generalizations about culture. A novel is not BuzzFeed or NPR or Instagram or even Hollywood. Let’s get clear about that. A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness. We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media. We have imaginations for a reason. Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture. Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did. We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?

I read Moshfegh as critiquing art that is narrowly obsessed with explanation, with staking out a clearly legible political stance. But that doesn’t, I think, mean that art is apolitical and has nothing to say about politics and society! When art is freed from being too didactic, it may actually have more to offer us—more subtlety and vigor and precision in its depiction of how people work, and how the world works, and all the pain and suffering and joy we experience through our interactions with the world.

The pitch

Gogarty’s book—as well as Sedgwick and Moshfegh’s observations—made me interested in the following questions:

What does it mean to have a novel that is politically engaged (but not politically unsubtle)?

Why are paranoiacs and conspiracy theorists often storytellers, presenting narratively-driven evidence about their ideas?

Is it wrong to feel paranoid about everything around you? Especially since that paranoia can be legitimized by the genuinely difficult political situation we find ourselves in?

The best nonfiction books, I think, offer you ideas and frameworks that are useful even beyond the specific content of the book. So while Gogarty’s book is about contemporary visual art, I really wanted to apply her ideas to contemporary literature.

Here’s the pitch I sent to the Cleveland Review of Books, where I outlined a tentative plan for how to do so:

I loved working with Philip Harris on my CRB review of Kanai's Mild Vertigo, and I'm writing to pitch another piece on Larne Abse Gogarty's What We Do is Secret: Contemporary Art and the Antinomies of Conspiracy (Sternberg Press/MIT Press, June 2023).

While the book focuses on visual, video, and installation art, many of its ideas feel relevant [to] literary art as well. I'd love to write a review that draws the following connections:

Internet art/novels and conspiracy theory: Gogarty discusses what characterizes internet-inflected art, and why so much of it focuses on conspiracy theory-style thinking. (On the left wing, for example, this takes the form of mapping CIA influence and US military intervention overseas.) Would like to relate this to novels where the protagonist becomes obsessed with resolving some mystery in their personal life and/or political world, and whether those investigations are helpful or harmful to those characters. Possible works: Lauren Oyler's Fake Accounts (2021), Tao Lin's Leave Society (2021), Hari Kunzru's Red Pill (2019).

Political art/paranoid reading: Gogarty describes how many “legibly political” artworks involve tracing, conspiracy theory style, how governments and corporations harm people. Sometimes this art ends up repeating messages we already know (American imperialism is bad, racism is bad) and over-explains it to the viewer, instead of inviting reflection. I'd love to relate this to Eve Kokofsky Sedgwick's ideas on paranoid reading versus reparative reading—what is the goal of art that explains what we already know? At what point does explaining and detailing harm become politically useless and aesthetically boring?

I attended the launch event at Printed Matter a few weeks ago and was impressed by how rich and engaged the Q&A around the book was—there are so many useful ideas in What We Do is Secret for thinking about politically engaged art and literature.

Please let me know if this sounds like a good fit for the CRB!

I don’t think I fully understood this until after my pitch was accepted, but this was a much more ambitious review essay than I’d ever done before. Part of the complexity came from trying to write about 4 books at once (and I later included a fifth book, Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger, into the essay as well). On a purely technical level there’s a lot that needs to happen: deftly and swiftly synopsizing each book; making a coherent case for why all those books were related to each other; establishing some argument for the essay that’s less Here’s 4 books I want to talk about! and more Here’s what these 4 books says about human nature/contemporary life/art/politics…

But I also think it’s very exciting to embark on projects that are a little beyond one’s current capacities. I didn’t feel qualified to write an essay like this yet. So what? It’s my belief that the energy and dedication you bring to the project is what ends up making you qualified. You’re passionate about the work and its potential, so you do everything possible to close the gap between your current self and the self who is capable of doing the work.

(For more on this, you can read my earlier post about the philosopher Agnes Callard and the work of being an aspiring writer.)

Researching and writing the essay

I used to think that research and writing were two distinct steps that had to be completed in that order. First, you do all the research. Second, when you know everything you want to say and what your argument will be, you write the piece.

The more I write, the more I realize how incorrect this model is—how it fundamentally misunderstands the co-constitutive nature of these 2 activities. As Mandy Brown (web designers and developers may know her as the former editor-in-chief of A Book Apart) says,

I’m not sure where the advice to “write what you know” originates. If I could locate it, I would pull it out at the root and then poison the ground from which it grew. You cannot know what you know until you’ve written it. As you write, you learn what you know—or, more likely, what you don’t know, which, let’s face it, is most everything.

So “working on the essay” typically meant: Reading a little bit; writing down little phrases or paragraphs that were mostly useless but sometimes contained a key insight; reading a bit more; getting bored of my “required” readings and taking a break to read something else; finding an unexpectedly useful insight from a seemingly-unrelated book or essay; talking to someone about the essay, becoming excited about a new idea they raised, going back to my draft and writing a bit more…

There were 2 forms of research I was doing, essentially: reading related works, and talking to other people to synthesize my ideas and receive new ones.

Research through reading

One theme that repeatedly came up in my reading was that conspiracies do exist. It’s actually not that easy to figure out what’s a “conspiracy theory” (typically understood to be illogical and unfounded) and an actual theory. “[I]t seems,” as Alenka Zupančič observed, “that conspiracy theories simply cease to be considered conspiracy theories when they turn out to be true.” One of the strangest things about American political discourse over the last few years has been the idea that it’s epistemologically straightforward to separate “fake news” from “real news,” and that anyone who believes in the wrong thing is just intellectually impoverished. That felt like an important idea to include in the essay—where I end up posing the question “What’s the difference between conspiracy theory and critical theory?”

Another theme that I became very intrigued by was the the sheer variety of conspiracy theories. There are right-wing and left-wing conspiracy theories, of course, but if you look at Wikipedia’s list of conspiracy theories, there are theories like Holocaust denialism, the Sandy Hook school shooting being faked…and the theory that Avril Lavigne was replaced by a body double. These feel like very different types of theories! And the 3 novels I wanted to analyze showed a similar range: Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill is about ethnonationalist conspiracy theories (and also about left-wing theories about anonymous internet posters mobilizing to elect Trump)…Tao Lin’s Leave Society is focused on where the medical establishment is wrong and what holistic remedies might be more useful…and Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts is about a boyfriend secretly promulgating 9/11 and antisemitic conspiracy theories, while his girlfriend tries to understand why this nice, well-off Jewish man is posting such deranged memes.

I ended up proposing 2 categories of conspiracy theories:

Let’s say that there are two kinds of conspiracy theories. The first, big C conspiracy theories, operate at the level of nation states, ethnic groups, and politics. Two of the most insidious examples are Holocaust denialism and Great Replacement theory (the belief that elites are replacing white people in Western countries with non-white immigrants). A big C theorist, in Richard Hofstadter’s characterization, “traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values. He is always manning the barricades of civilization.”

…If big C conspiracies take on the vast sweep of national politics and racial strife, then little c conspiracies operate at a more intimate, domestic scale. Sometimes, they focus on the self and health: Are seed oils going to kill me? Is mewing better than braces, and is the orthodontic establishment suppressing the truth?…

The comparatively small stakes of little c conspiracy theories can make them seem hardly worthy of the name. But they’re often tied to larger anxieties about society, and can reflect a politically potent distrust of professional elites.

(I mentioned, earlier, how certain ideas are “portable” and can be applied to new contexts. This idea of carving out the world into a big X versus a little x division of a big X versus a little x comes from a design professor in undergrad, who used big D design to refer to, say, Charlotte Perriand designing a chair—and little d design to refer to someone adding a cushion to their chair to make it match their body, lifestyle, and needs better.)

I was also surprised by how much of my undirected reading (simply clicking on links and buying books without my essay in mind) ended up informing the writing. One example is this post from the artist

’s Substack, about a series of artistic works inspired by a Quartz article, “All the Wellness Products Americans Love to Buy are Sold on Both InfoWars and Goop.” Citarella’s work underscored an argument that the scholars William Callison and Quinn Slobodian make in their Boston Review article about COVID creating new “diagonalist” political alliances that unite granola-mom/wellness-influencer types with anti-lockdown populists.One of the most useful ideas for the essay came from a seemingly unrelated book: The Unforgivable: And Other Writings, a collection of essays by the Italian writer and translator Cristina Campo (1923–1977). Campo is primarily concerned with literature, Catholicism, myths, and fairy tales—and I was primarily interested in Campo’s book because she has a truly singular style, meditative and aphoristic and lovely. I was struck by one passage, in the essay “Deer Park,” where she writes:

I love my time because it is the time in which everything is failing, and perhaps precisely for this reason it is truly the time of the fairy tale. And I certainly don't mean by this the era of flying carpets and magic mirrors, which man has destroyed forever in the act of making them, but the era of fugitive beauty, the era of grace and mystery on the verge of disappearance, like the apparitions and arcane signs of the fairy tale: all those things that certain men refuse to give up and love all the more, even as they seem to be increasingly lost and forgotten. All those things we must set out to find, albeit at the risk of our lives, like Belle's rose in the dead of winter. All those things that, as time wears on, are concealed beneath ever more impenetrable disguises, in the depths of more horrible labyrinths.

There was something strangely alluring about the bolded sentence, and the feeling that Campo expresses in it. What does it mean to love the world when it’s falling apart around you? Do we rely on fairy tales more in times of crisis? In earlier drafts of the essay, I quoted Campo directly but it didn’t feel right—she’s writing about a different historical moment, and what I’m getting from her is this evanescent, fragile idea of fairy tales in a failing world. But her influence is clear in some of the final paragraphs of my essay, where I write:

Online—where we confront all the crises of capitalism, society, and politics—conspiracy theories are fairy tales for the paranoid. The Brothers Grimm had the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel, two angelic German children nearly taken in by a witch’s trap. We have QAnon’s contemporary retelling, where children are endangered instead by a sex trafficking ring run by Democratic party elites.

These dark narratives have a function: they teach us to fear the primordial, foundational evils of the world. But they also promise a conditional escape: if you attain the right knowledge and listen to the right people, you might be able to save yourself and those you love.

Research through conversation

The research process also involved talking to everyone—friends, coworkers, my girlfriend—about conspiracy theories. One of the things I love about having a project is how purely fun it is to get different perspectives on it. And conspiracy theories are such an appealing and energizing topic of conversation! I talked to people about Kate Middleton’s mysterious disappearance from social media; a 9/11 truther organization that emailed a friend’s physics PhD partner with a very professionally produced, multi-page PDF about the structural integrity of the Twin Towers; and an incredibly extensive Twitter thread about obesity in America (approximately 200 tweets long) that begins, mysteriously and provocatively, with the phrase “The study of obesity is the study of mysteries.”

Some particularly useful conversations:

In late February, I was speaking to

about the review, and as soon as I mentioned Kunzru’s book Red Pill, he recommended Geoff Shullenberg’s essay “Redpilling and the Regime.” In it, Shullenberg examines the phrase “taking the red pill” and what it says about someone’s relationship to authority and truth. I loved this insight:If the metaphorical possibilities of redpilling are so varied, that’s partly because it is an update of one of the oldest stories about knowledge in Western culture…Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

In…March, I think? I had an exceptionally useful conversation with Peiran Tan about left-wing and right-wing conspiracy theories. I must have mentioned Citarella’s observations about the InfoWars and Goop audience sharing the same wellness products (because they have a “shared material politics of hyper-individualism and self-sufficiency”). Peiran shared another great example of 2 aesthetically distinct groups that share certain ideological tendencies—in in this case, a distrust of power. On the surface, a stealth-wealth techwear guy wearing Arcteryx and obsessed with privacy and evading surveillance seems totally distinct from a camo-wearing, Jeep-driving rural American railing against the government’s gun control policies. What brings these two groups together, however, is that they don’t trust the government to keep them safe—they’d rather take matters into their own hands. He also helped shape my thinking on conspiracy theories as contemporary fairy tales, by noting that conspiracy theories are often allegories about power.

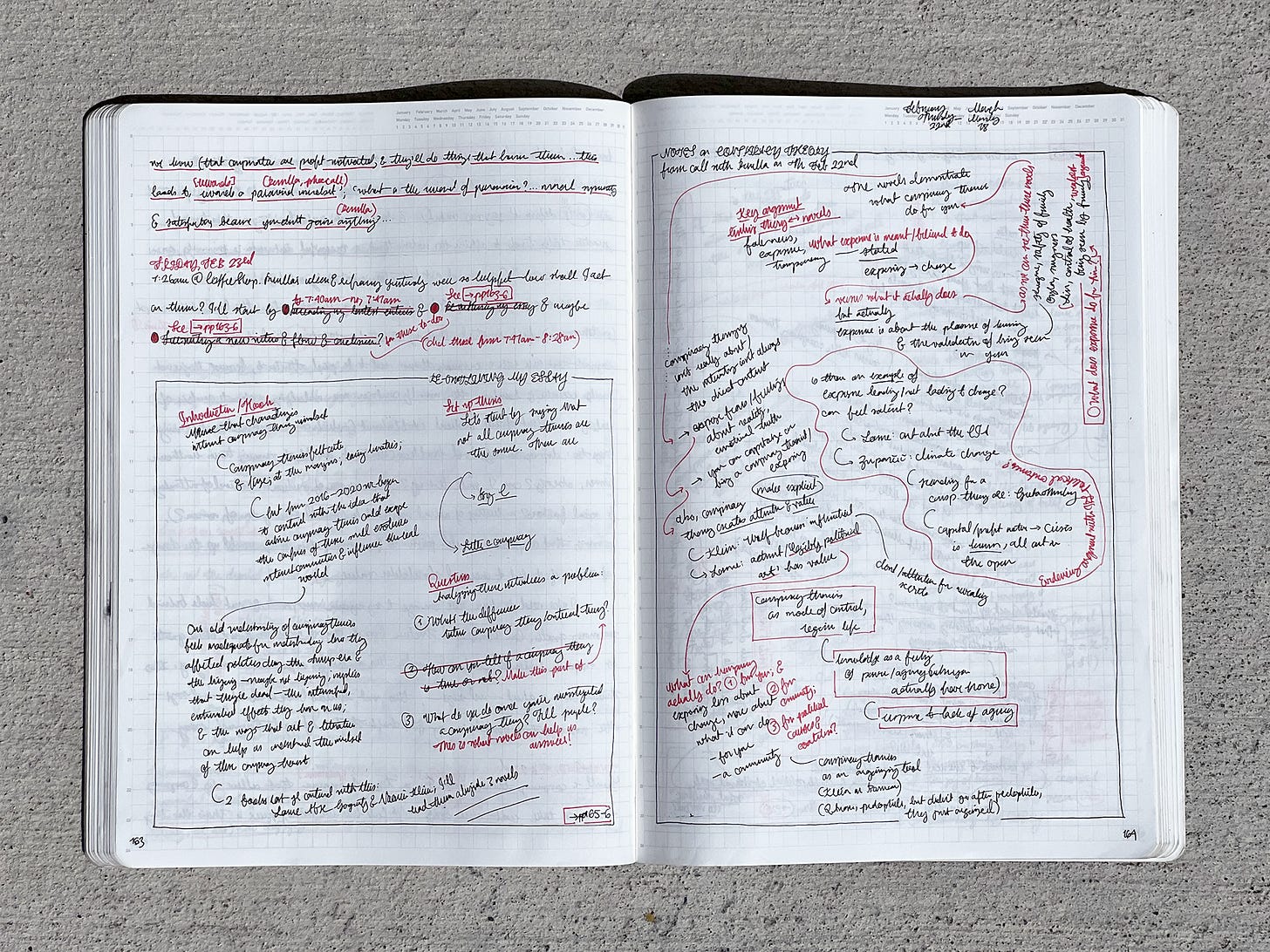

At some point I was stuck! very stuck! on my argument, because I couldn’t quite figure out how to draw a connection between the big C conspiracy theories (about race, ethnicity, nation-states) and the small c ones (about health, wellness, and interpersonal relations). Perhaps, my girlfriend suggested during a phone call, it’s that “small c conspiracy theories normalize a type of paranoia that allows big C conspiracy theories to take root more easily.” I remember running to get my notebook during our call, so I could write her observation down and elaborate on it later. She also posed a very useful question—“What is the reward of paranoia?”—that helped sharpen my analysis of the 3 novels.

Revising

It’s probably obvious now that I love thinking about creative process, and I love process artifacts. Why?

One of my favorite books on design is Matthew Frederick’s 101 Things I Learned in Architecture School, which sounds like shallow clickbait but is actually one of the most concise and profound books on designing and building that I’ve ever read. Many of the lessons are generalizable outside of architectural practice, like these 2:

Improved design process, not a perfectly realized building, is the most valuable thing you gain from one design studio and take with you to the next.

The most effective, most creative problem solvers engage in a process of meta-thinking, or "thinking about the thinking."

I obsess over process because the thinking about the thinking, the self-reflection on what I’m doing and how the final outcome emerged, seems to make me a better designer and writer. For writing, in particular, I’ve become quite interested in observing my revision process, and how a very raw, unpolished first draft becomes something fluid, swift-moving, and well-argued.

Last Friday evening, I was sick at home and realized that writing CSS is, for me, much easier than writing prose. So I made the following website, which presents 3 different versions of the intro to “Feelings Over Facts: Conspiracy Theories and the Internet Novel,” with some highlighting to show particular discussions that changed over time.

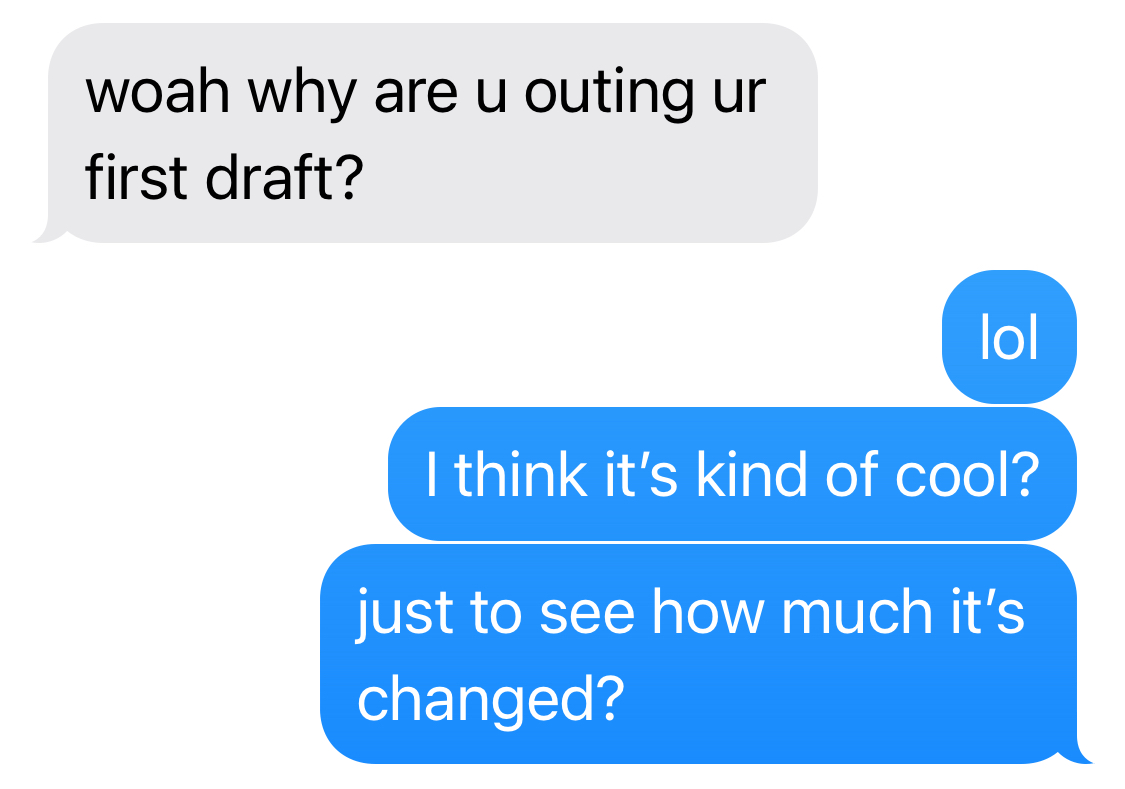

When I sent the website to my friend Ryan, he asked:

But the bigger reason for doing this (even though I am very, very self-conscious about my first draft) is that I am intensely nosy about other people’s first drafts! I want to know what writing looks like before it’s ready for an audience, and what the reader does to make it ready.

Why make a website for this?

There’s a certain kind of writing advice that I am desperate to find, and that is actual examples—case studies, if you will—of how other people revise their writing. I’m not sure why this is so hard to find! The internet is inundated with writing advice, and someone is always waiting in the wings to recommend Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird…but much of that advice answers questions like:

How do you take yourself seriously as a writer?

How do you not get discouraged?

How do you keep on going?

But what if your problems are not emotional, but tactical? What if you’ve already decided to take your project (and your writing practice) seriously, and you just need to know—how can you improve your writing? How can you, very concretely, make it better?

Examples of the revision process are hard to find, but I’m delighted whenever I come across one:

For prose writers, I like Lydia Davis’s Essays One, specifically the essay “Revising One Sentence,” where Davis—the queen of the very short story—shows how she works on a single sentence and weighs different adjectives, verbs, and phrase constructions to arrive at a particular image.

For poets, the paper “Elusive Mastery: The Drafts of Elizabeth Bishop's ‘One Art’” (by the literary scholar Brett Candlish Miller) examines the 17 different drafts that Bishop wrote, over the course of about 2 weeks, to arrive at her final and justly famous poem.

And thanks to the poet Hua Xi, I’ve just discovered that Guernica used to have a section of their website titled “Back Draft,” where different poets, fiction writers, and translators were interviewed about their revision process—with examples of a first and final draft of a piece!

If you have any other examples, please let me know!! But for now, here’s my own contribution to this (imo) very essential and underrepresented genre.

What lessons did I learn from the revising process?

I’ll say a few words about what I learned from making this website, and comparing the different versions I wrote.

The first draft: When I write a first draft, I tend to over-write and go on at great, tedious length. I start with whatever ideas come to mind, and whatever references come to mind (usually whatever I’ve read in the past week) and try to marshal them into paragraphs. When I wrote this particular first draft, I was thinking about conspiracy theories in the Trump era, and how strange it was to have a US election happening with hardly any news coverage. Unlike the last 2 American presidential elections, I wasn’t constantly inundated with articles about polling results and predictions. So I wrote quite a lot about Trump (on the website, this is highlighted in orange).

But I just felt so fatigued, so bored writing about Trump. I actually left a note in my draft that said Maybe Trump is too exhausting a topic to start off with; maybe open with the meme, because at some point I began writing about visual and verbal memes for conspiracy theorists online (the Pepe Silvia meme discussion is highlighted in aqua; the discussion of “taking the ___ pill” is highlighted in red) and that seemed far more interesting and vital.

The draft I submitted: So the next draft—in the middle column—put all the Trump discussion further down, and kicked off with the meme discussion. That felt better. And by the time I wrote that draft, I’d done a lot more reading and wanted to include a brief history of the term “conspiracy theory,” from the 1960s to now. This draft felt more precisely argued and it had a more compelling opening.

But when I submitted this to my editor, Philip Harris, he suggested that the intro felt a bit too long—you had to read a thousand words in (!!!) before getting to a paragraph that stated, quite plainly, that this was an essay about 2 particular nonfiction books about conspiracy theories (highlighted in purple on the website).

The final review: One of my major goals for the final draft was to make the intro much sharper and swifter. You’ve probably come across this idea that online readers have a short attention span, and require short pieces, clickbait headings, and stylishly controversial openings in order to keep on reading. But I wonder if we’re underestimating people’s desire to read longform content—and if being in thrall to the mystical short attention span is doing a disservice to a reader’s intelligence. A while back, I came across a more intriguing idea: that readers have a short enchantment span, and you need to very swiftly establish that the writing in front of them will be interesting, fascinating, delightful, and worth reading.

So that’s what I tried to do in the final intro—I made the discussion of the memes much faster; I moved up the purple-highlighted bit where I introduce the books; and I rearranged the essay so that more of the historical context appears later on, when (presumably) the reader is already enchanted and interested in learning more.

So that’s the story of my essay! You can read it here. Endless gratitude to my editor and to the Cleveland Review of Books for letting me write this.

Three (somewhat) recent favorites

Kathleen Ossip’s poetic critique of “the facts” ✦✧ What’s the difference between investigative journalism and conspiracy theory? ✦✧ The French have a word for this

This week’s recent favorites are all on-theme, and broadly about conspiracy theories, paranoia, and the rise of the alt-right in the US, UK, and Europe…but I’m hoarding the usual design/architecture/fashion/art links for the next post!

Kathleen Ossip’s poetic critique of “the facts” ✦

The poet Kathleen Ossip’s “The Facts,” from the Paris Review’s winter 2021 issue, is very relevant to an idea Gogarty and Klein both discuss: that facts and transparency alone will not solve our political problems.

Here are the first few lines:

The facts sit in an ordinary room. They resemble people:

stubborn and without imagination.The facts begin to chatter: Better days coming, better days

coming. They arrange themselves in the shape of a lie.They’re cheating: they only work in the past tense.

They fake objectivity. They decide unanimously.

What’s the difference between investigative journalism and conspiracy theory? ✦

While working on the piece, my editor sent me an article about the investigative journalist

, who’s had a long and storied career writing about things like:The US government’s coverup of the Mỹ Lai massacre during the Vietnam war, where the US military killed hundreds of civilians, for the New Yorker (Hersh won the Pulitzer Prize for this)

The CIA’s extensive domestic spying operation during Nixon’s presidency, including multiple illegal break-ins and wiretapping, for the New York Times

And, more recently, the US military’s torture program at Abu Ghraib, for the New Yorker

In 2015, however, Seymour published an article for the LRB that accuses the US government of fabricating certain details about Osama bin Laden’s death. For some reason, this particular article was met with a great deal of pushback from other journalists; one representative article, published in Slate, had the sneering title “What InfoWars Conspiracy Theories and Hersh’s Bin Laden Story Have in Common.”

The n+1 article “Evil but Stupid,” published that fall, investigates where this pushback came from. Hersh’s claims seemed plausible, and a number of other investigative journalists said that it was supported by their own sources. The n+1 article suggests that Hersh was simply out of step with the optimistic Obama-era climate, where the president had “promised a new era of transparency…The press relaxed so drastically that they couldn’t easily change tacks when Obama began to betray his promises.” Even though Hersh was revealing actual conspiracies, it was easier to just dismiss him as a conspiracy theorist:

[A]ll the charges leveled against Hersh’s fondness for conspiracy theories are belied by the many conspiracies disclosed in recent years…[such as] the huge conspiracy to guard the National Security Agency’s data collection programs, which might have succeeded for who knows how long were it not for the thumb drive of Edward Snowden…[and] the February 2010 massacre of five innocent people, including two pregnant women, by US Special Forces operators in Gardez, a provincial capital in Afghanistan…

In fact, given the zeal for secrecy that characterizes Obama’s presidency (to say nothing of its enthusiasm for extrajudicial assassinations), the question becomes: Why isn’t the media more paranoid? What may be irking journalists about Hersh is the way he harks back to an era of heroically paranoid journalism — the kind that once brought down governments — that they no longer feel themselves to be living in…one role of the journalist is to debunk crazy conspiracy theories, but another, more difficult role is to expose real and harmful conspiracies, of which there have been many.

But that was 2015. In 2016 Trump was elected. It’s interesting to read the n+1 article now, and realize how much the legitimacy (or illegitimacy) of paranoia rests on the perceived “normalcy” of the current political setup.

The French have a word for this ✦

Back to 2024 politics. After the EU parliamentary results came out, I found myself wanting to understand a slightly longer history (as in, the last 5–10 years) of the National Rally in France, Meloni’s Brothers of Italy in…well, Italy, and AfD in Germany.

I ended up finding this 2017 Economist article, on Marine Le Pen versus Emmanuel Macron, that introduced me to a very useful term: dégagisme.

One by one, political leaders of the ancien régime, who had confidently been preparing to face each other at the presidential election this spring, have been carted off to the guillotine on a wave of revanchist fury. France is in the grip of what might be called “dégagisme”: a popular urge to hurl out any leader tainted by elected office, establishment politics or insider privilege. Less clear is which sort of outsider French voters want instead.

There’s arguably even more “revanchist fury” present today. Worth noting that the leader of Le Pen’s party is now the telegenic (by which I mean, Tiktok-genic) 28-year-old Jordan Bardella. Less controversial than Le Pen; less weighed down by the National Rally’s historic antisemitism; more effective at pushing an anti-immigrant message, since—as the son of Italian immigrants—he can more easily claim that migrants who fail to assimilate (in particular, migrants that he suggests are bringing “totalitarian Islamism” into the country) will mean the “death” of France.

This was SUCH a great read. Loved getting a peak into your writing process. Please do more of these!

C.

This was a really fun peek under the hood of the essay. I’m always recommending Samuel Delany’s book ABOUT WRITING—he doesn’t quite do “case studies” (although he does give an incredibly exhaustive and instructive critique of a bad workshop story) but he does get VERY specific about the actual process of writing, in a way this reminds me of.