seeing like a simulation

my LARB essay on SimCity, software criticism, and utopian urbanism ✦

One of the great lessons of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is that the things you were obsessed with as a child (hawthorn blossoms, aristocratic grandeur, the difficulty of falling asleep) are excellent material for one’s writing. But Proust grew up in a bourgeois family in fin de siècle France and spent a lot of time in the Faubourg Saint-Germain; I grew up in California in the early 2000s and spent a lot of time on the internet. As a result, my childhood obsessions were architecture blogs, videogames and New Urbanism memes.

My latest piece, for the LA Review of Books, compresses all of these obsessions into a review of Chaim Gingold’s Building SimCity: How to Put the World in a Machine. Gingold’s book describes the intellectual and cultural influences that led to the creation of a very unusual kind of game—one that turned the real-life profession of city planning into a form of entertainment. Stewart Brand described the book as “the best account I've seen of how innovation actually occurs in [computing].” I’d agree!

In this post, I’ll write a little bit about the process of pitching and writing the review—it includes a lot of my convictions on how to write about software, art, and real-life urbanist controversies. Here’s what I’ll cover:

Pitching the LARB

How to write about software, cities, and art

An unusually spirited diatribe about bad political writing

Pitching the LA Review of Books

I’ve read the LA Review of Books for many years and really like their range. They publish reviews of literary fiction—but also quite a few reviews on academic monographs in the humanities, social sciences, and philosophy. So pitching them on a MIT Press book felt perfect.

Here’s the pitch I sent:

I’m a writer and software designer in San Francisco […] I’m writing to pitch a review of Chaim Gingold’s Building SimCity: How to Put the World in a Machine, published on June 4 by MIT Press.

While some videogames promise an escape from reality, others—like SimCity—turn real-life problems into entertainment. In Building SimCity, Gingold, a game designer and historian, describes the philosophical underpinnings of simulation games and how SimCity’s creators used ideas from urban planning and systems theory. The book is neither an enthusiastic fan’s account nor a dry, moralizing critique. Gingold writes about the actual gameplay, but situates it in the history of American computing and Silicon Valley entrepreneurship.

The game is very popular with Bay Area technologists, who have started projects to build an ideal city or create para-academic urban research groups after being frustrated by San Francisco politics. The philosopher C. Thi Nguyen, in Games: Agency as Art, discusses how games can teach players new forms of agency (within a pleasantly simplified world), that can translate to real life. I’d like to use his argument to think about how SimCity models urban life: infrastructure is simulated in detail, but urban politics and bureaucracy are not. This makes it easier for players to treat complex issues, like homelessness and gentrification, in mechanistic ways (on forums, players often ask “How do I get rid of homeless people?”).

[At the end of the email, I mentioned some previous research I’d done in the history of information/technology + clips of other reviews I’ve written]

A few notes on this pitch:

Bio — I started the email with 2 “credentials” (my day job as a software designer + living in San Francisco) that were relevant to the book and to my proposed argument for the review. I’ve noticed (in myself and others) a certain level of embarrassment about having a day job…but I think the non–literary parts of our lives can provide the topics and intellectual frameworks for our writing.

Argument — My favorite reviewers often use a book as a starting point for bigger social, cultural, political and intellectual questions. I wanted to do the same here—so I sketched out some provisional angles (the California Forever project to build a new city in northern California; homelessness and housing policy in SF)

Other books — I’d been meaning to read the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art for some time (I actually hadn’t read it fully when I sent this pitch…I’d just seen a lot of references to it), and I believed that it would have useful frameworks and ideas for my review.

The LARB has a number of section-specific editors; after consulting their masthead, I sent this pitch to Michele Pridmore-Brown, the science and technology editor. (Pridmore-Brown was really lovely to work with! Very responsive and encouraging.)

For examples of previous pitches and reviews, read—

How to write about software, cities, and art

There’s a saying, often attributed to the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, that “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.”1 When I was writing my LARB piece, I was thinking of 3 different rephrasings of this:

We shape our software [which includes tools and toys], and thereafter our software shapes us

We shape our cities, and thereafter our cities shape us

We shape our art forms and artifacts, and thereafter our art shapes us

On software

Software, as my friend Sheon Han has written, is “a defining artifact of our time,” in the same way that the novel was a defining artifact of the 18th and 19th centuries. How should people write about software in a way that captures its influence and complexities? Both Sheon and I are interested in writing that is similar to art and literary criticism—where historical, theoretical, intellectual and aesthetic concerns come together.

Let’s call these people writing like this software critics. They might include people like Han, Kai Ye (a former colleague who wrote an excellent essay on the encrypted messaging app Signal), the artist and educator Laurel Schwulst , and the new media artist and researcher Eryk Salvaggio. And Chaim Gingold, of course—Building SimCity is an excellent example of book-length software history and criticism!

But I want more software critics, and more venues to publish this kind of work! Two of the best venues—Real Life and WIRED’s software review column—are now defunct. So my strategy, for now, is to advocate for this kind of writing in publications like the LA Review of Books.

I’m inspired, in part, by the critic Ryan Ruby, who believes we’re presently in a golden age of literary criticism. After listing some of his favorite critics and publications, he wrote:

If it is to be objected that a group of 50–100 critics writing for one to two dozen venues which reach an audience that maxes out in the low five digits is nevertheless a very small group of people, I will just say that, historically speaking, literary revolutions have been made by far smaller groups than this.

Ruby’s essay is invigorating, especially since most discussions of literary criticism are narratives of decline. And now that I’m revisiting it, I can’t help but ask: When is the golden age of software criticism going to begin? And how can I—informally through this newsletter, and in work published elsewhere—contribute to it?

On cities

Software critics can also learn, I think, from architectural critics and urban theorists. The connection between software and cities is actually quite profound. Both are complex systems created over a long period of time, by multiple people, involving multiple academic and professional disciplines. And the history of computing has been deeply influenced by architectural theorists like Christopher Alexander, whose A Pattern Language was enthusiastically taken up by computer scientists and software designers in the late 20th century. (The concept of a “software design pattern” is drawn from Alexander’s work.)

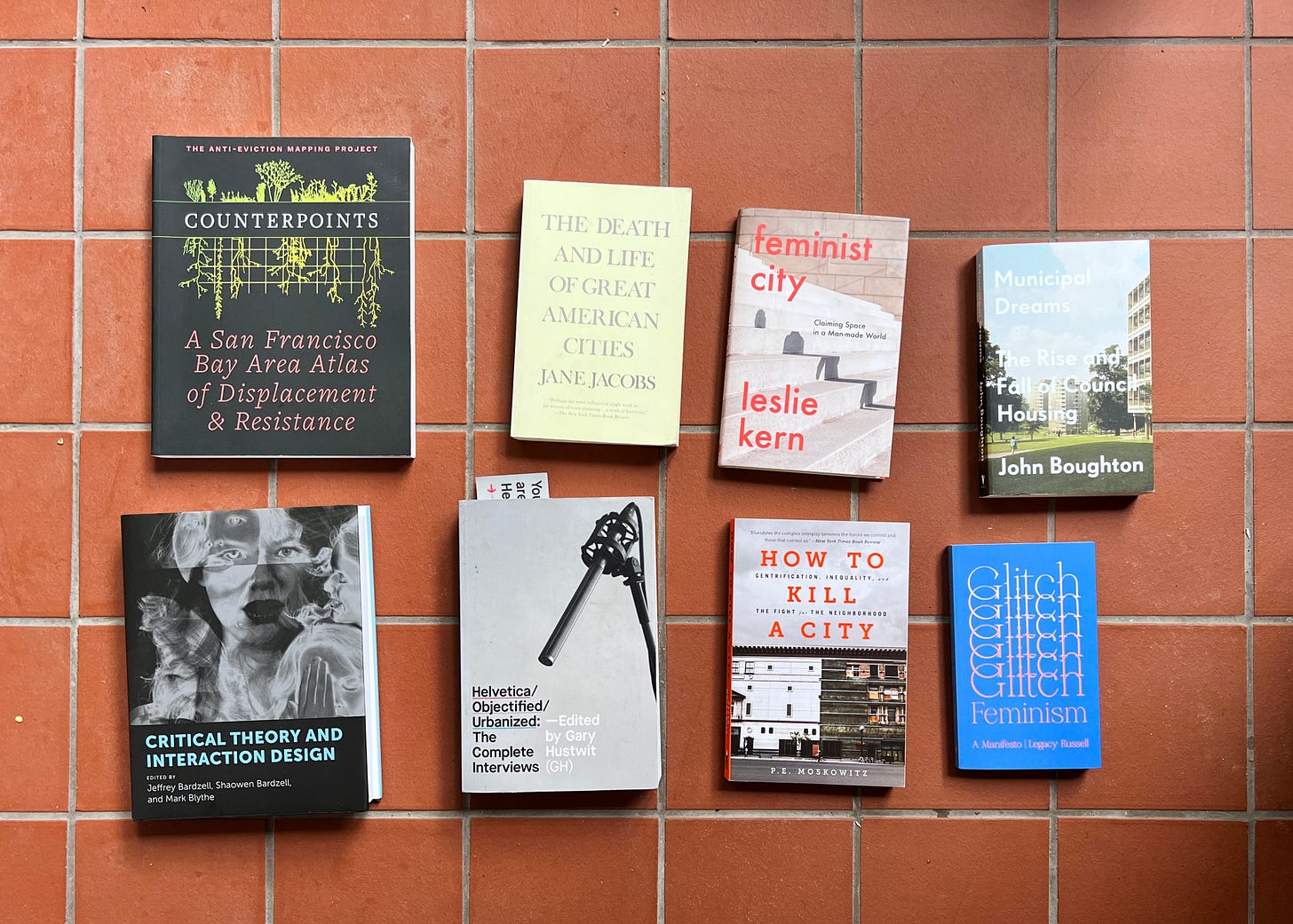

On a purely personal level, I also just love reading about cities and buildings. I As I was figuring out how to draw the connection between software about cities to real-life cities, I started pulling from my bookshelves:

There’s something deeply satisfying about curating a personal library over time. Some of these books I’ve read in full (❷ ❸ ❻ ❼); others are waiting for the right time and the right project. My review of Gingold’s Building SimCity gave me an excuse to return to many of my favorite books on architecture and urbanism—and discover new ones as well.

What designers, architects and urbanists have in common is a belief that our built environment shapes our lives. But because digital built environments are fairly new, the ways people write about them are still immature. Unless, that is, they draw from more mature disciplines concerned with the physical built environment.

It helps, too, to draw on disciplines like sociology and anthropology, which are concerned with how people and societies operate. The day my pitch was accepted, I started reading the anthropologist and political scientist James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed.2 Reading Scott’s book was a bit of an impulsive decision, but it turned out to be key to my argument. As I wrote in my review:

To help players realize their ambitions, SimCity provided multiple layered maps. Crime, pollution, traffic…and more were clearly visualized—and often quantified—to help players understand the impact of their interventions…All of this made the simulation richly detailed and inviting to interact with. And it made players more powerful. “Legibility,” the political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott proposed, “is a condition of manipulation.” In Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1994), Scott describes how real-life bureaucrats trying to change the world first needed its elements to be “observed, recorded, counted, aggregated, and monitored. […] [T]he greater the manipulation envisaged, the greater the legibility required to effect it.” In the real world, perfect information, and therefore perfect control, is impossible…But in SimCity, the simplified map is reality. The game realizes the unattainable dream of Scott’s high modernist city planners.

I wrote about James C. Scott’s critique of city planners and architects like Le Corbusier here—

On art

The 2 books that most helped me frame my review were Scott’s Seeing Like a State and C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art. To expand on Nguyen’s book (which I recommend unreservedly to anyone interested in new media, art, and philosophy)—

I loved Nguyen’s book because it simultaneously makes a case for videogames as an art form—alongside literature and film—while also emphasizing how games are distinct from these other forms. Games are kind of like novels, and kind of like cinema. But they also, as Nguyen argues, “offer us access to a unique artistic horizon and a distinctive set of social goods”:

[Games] are special as an art because they engage with human practicality—with our ability to decide and to do…In ordinary life, we have to struggle…[and] the form of our struggle is usually forced on us by an indifferent and arbitrary world. In games, on the other hand, the form of our practical engagement is intentionally and creatively configured by the game’s designers…we can engineer the world of the game, and the agency we will occupy, to fit us and our desires.

Like Nguyen, I don’t think it’s useful to analyze games on a formal level using the exact same techniques used for literature and film. But on an ideological level, there are some insights from literary criticism that are helpful in thinking about games. While writing my Building SimCity review, I kept on thinking about a particular question: Are games bad for us and bad for society? What are the ideological risks involved in creating fictional worlds?

What’s not dangerous about fiction?

There’s a persistent anxiety that fiction—and specifically “bad” or “obscene” fiction—has a corrosive effect on people. The writer Lyta Gold’s forthcoming book Dangerous Fictions: The Fear of Fantasy and the Invention of Reality (you can preorder it here!) is focused on these concerns. “Fear of fiction,” Gold writes in the introduction,

seems always to boil down to fear of one’s society and the people who live in it. Other people’s minds are frightening because they are inaccessible to us; one way we can know them is through their representations in fiction. We know that fiction affects us profoundly and mysteriously, and that other people are affected just as strongly and unpredictably as we are. Which means it’s at least theoretically possible that art could seduce our fellow citizens into wicked beliefs.

This isn’t a new debate. Plato feared that depictions of people behaving badly was an “endorsement and license” for the audience to behave badly, too. And debates around whether Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita was appropriate to publish, as Thomas Harding observes, were informed by an 1868 British court ruling which claimed that obscene literature would “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influence.”

My own stance is informed by something the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh wrote in response to a question Bookforum posed in 2021: “What forms of art, activism, and literature can speak authentically today?” Moshfegh’s response was the following:

I wish that future novelists would reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society. Art is not media. A novel is not an “afternoon special” or fodder for the Twittersphere or material for journalists to make neat generalizations about culture. A novel is not BuzzFeed or NPR or Instagram or even Hollywood. Let’s get clear about that. A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness. We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media. We have imaginations for a reason. Novels like American Psycho and Lolita did not poison culture. Murderous corporations and exploitive industries did. We need characters in novels to be free to range into the dark and wrong. How else will we understand ourselves?

When I was growing up, videogames were often seen as inherently violent and sexist. It wasn’t uncommon to see pundits assert that Grand Theft Auto would encourage criminality, or that sexist depictions of female characters were impeding the feminist project. While I think specific depictions of violence and gender might be problematic, I don’t think that depicting these things—or allowing players to enact them in a game—is inherently immoral or corrupting.

That’s why I wanted to quote a point that Gingold makes in Building SimCity—

SimCity reproduced authoritarian notions of governance and city planning, simpleminded ideas about crime, policing, and taxation, and a downright colonial and extractive outlook—unexceptional shortcomings for a computer game.

—because, although SimCity lets you play as the authoritarian dictator of a city, it is not a fair claim to say that this turns people into authoritarians! Indeed, many players—like the architecture student Vincent Ocasla, who I mention in my review—have used SimCity to criticize authoritarian politics. Games offer a great deal of agency to their players, especially simulation games like SimCity. That agency can be used to affirm a wide range of political viewpoints—and it can also be used to simply play, without a coherent political stance involved.

What is dangerous about fiction?

But there are other dangers that videogames present, and once we move past the moralizing fears that Moshfegh criticizes, we can get to the really interesting problems.

I’ve been thinking about a Twitter discussion on the “surprising and non-obvious consequences” of reading a lot from a young age. Two of the consequences proposed are especially relevant to fictional books:

Reading encourages you to “[use] narrative logic in real life situations, for better and for worse”

And if reading means that “your social training data is biased towards drama & intrigue…you'll tend to create the same or feel bored by ppl.”

What, then, might be the non-obvious consequences of videogames? In Games: Agency as Art, Nguyen identifies two potential risks:

Value clarity — In games, your goals are very clear, and they are typically measured in straightforward and even quantified ways. This makes it easier to chase a specific goal, “in all its simplicity and selfishness…We need not balance our needs with the needs of others, or even with our own other complex desires.” In the real world, our values are often more subtle. How do you optimize for beauty and goodness? In the real world, it’s hard to say. In a game, it’s very easy—and there’s probably a points system involved.

Instrumentality — In games, we tend to adopt a mindset where all that matters is our goal and our experience. “We don’t need,” Nguyen writes, “to treat others’ interests as valuable…[or] treat them with, as the Kantians might put it, dignity and respect. We are permitted to manipulate, use, and destroy.” While this mindset tends to make games more pleasurable, it’s clearly disastrous to export outside of a game.

These qualities are what make games fun. But it’s possible, Nguyen argues, for these qualities to negatively shape how people perceive the real world.

Almost all players know that killing in games is only a fiction, and that they should not export pro-killing attitudes outside the game. And many players probably also understand that the all-consuming instrumental attitude is a temporary artifact of the game. The need to confine that attitude to the game context also seems relatively clear. But value clarity is a subtler feature of games…[which] makes it easier to accidentally export the expectation for value clarity out to non-game life. Games can present a fantasy of value clarity, but many players may not realize they are indulging in a fantasy at all.

There’s a nice parallel, I think, between Nguyen’s argument on the perils of in-game value clarity—and Scott’s argument, in Seeing Like a State, on the perils of state-enforced legibility. And hopefully I justified the connection in my LARB piece!

An unusually spirited diatribe about bad political writing

In my original pitch, I briefly mentioned an project, called California Forever, to build a brand-new city an hour’s drive from San Francisco. The project, which was lavishly funded by Silicon Valley VCs and entrepreneurs, has attracted a great deal of controversy. Because it touches on so many things I’m interested in (how technologists relate to and try to reshape the Bay Area; utopian New Urbanist projects; campaign finance and how politics is distorted by wealth; grassroots activists versus wealthy funders)…I really wanted to incorporate it into my essay.

The last section of my review is a history of California Forever, from 2018 to present. It’s an extremely ambitious and polarizing project! I wanted to do justice to the stated goals of the project (building a new city that follows best practices for dense, walkable, affordable, culturally rich, and environmentally friendly neighborhoods) and California Forever’s many detractors, who see it as a vanity project by out-of-touch elites. If you want to read more about it, here are some of the most interesting articles:

Jon Skolnik’s ‘“California Forever,” the Billionaire-Backed City No One Asked For’ in Vanity Fair (April 2024)

Benjamin Schneider’s ‘The real problem with California Forever, the Bay Area’s new billionaire-backed city’ for FastCo’s CityLab (January 2024)

Diana Lind’s ‘The Case For and Against California Forever’ on her excellent Substack newsletter (January 2024)

Noah Smith’s ‘The California Forever project is a great idea’ on his Substack (January 2024)

Sam Sklar’s Q&A with California Forever’s head of planning, Gabriel Metcalf, for Resident Urbanist (April 2024)

I was motivated, too, by a particular article that I really disliked. The journalist and former Democratic staffer Gil Duran’s “The People of Solano County Versus the Next Tech-Billionaire Dystopia,” for the New Republic, was a full-throated condemnation of California Forever that relied on (in my opinion) fairly slipshod reasoning.

Here’s what Duran’s piece seems to be doing:

In paragraph 5, Duran describes how one of the billionaire funders behind California Forever, Michael Moritz, saw the project as “a kind of urban blank slate where everything…[including] new forms of governance could be rethought.” But Duran isn’t quoting Moritz directly—rather, he’s quoting a New York Times article that paraphrases an email Moritz wrote.

Duran then asks: What could “new forms of governance” mean? He suggests that it’s similar to the special economic zones that the historian Quinn Slobodian describes in Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy. The book (I’m reading it now, and it’s excellent) describes various libertarian projects to create zones “freed from ordinary forms of regulation,” whether economic or political or both. Slobodian’s book is meticulously researched and very critical of these projects. Duran summarizes the book’s arguments in paragraphs 6–17. But the book, it should be said, does not mention California Forever or Michael Moritz in it. So how does Duran justify the connection?

He does so by talking about a completely different tech billionaire, Balaji Srinivasan, who is discussed extensively in Slobodian’s book. And he attempts to connect Srinivasan to the California Forever project by including the following evidence:

At a conference organized by Srinivasan on “network states” (autonomous states that act as alternatives to the nation-states we have today), a speaker had a slide with a rendering of the California Forever project. California Forever denied any affiliation with the speaker or the conference.

One of Srinivasan’s colleagues has invested in California Forever

Srinivasan’s book, a kind of manifesto for networks states, mentions 2 other people who have invested in California Forever

So the argument seems to be: Srinivasan is friends with all these people who are involved in California Forever; Srinivasan has a certain set of political standpoints; his friends must share them; and the project they’ve invested money into is a way to actualize those politics. As Duran writes,

Perhaps it’s a coincidence that Andreesen, one of Srinivasan’s longtime colleagues, is one of California Forever’s investors, and that Srinivasan name-checks two of the project’s other billionaire investors—Moritz and Stripe founder Patrick Collison—in his book. Maybe it’s just happenstance that their mystery project matches the trend of other proposed start-up societies around the globe, or that Moritz evoked the idea of new forms of governance in his investor pitch.

I feel very conflicted saying this, because my politics are probably more aligned with Duran’s than Srinivasan’s…but I think this is a fairly weak argument? There is no actual evidence that California Forever’s goal is to create an autonomous economic zone, within California, that somehow secedes from the state’s existing economic and political regulations. It’s possible that this is secretly the goal—but then I, personally, would want to muster stronger evidence than the vibes-based, guilt-by-association evidence that Duran musters.

I could easily make unprincipled arguments in the opposite direction. Like, I could point out that:

Michael Moritz and his wife have a charitable foundation, Crankstart, that has made grants to organizations like the Booker Prize, 826 Valencia, Code for America, ProPublica, Larkin Street Youth Services [which provides services to unhoused youth in SF], Centro Legal de la Raza [which provides legal aid to low-income immigrants in SF], Keep Oakland Housed, and more.

Moritz has also written an op-ed for FT criticizing Silicon Valley’s Trump supporters—who, he writes,

are making the same mistake as all powerful people who back authoritarians. They are, I suspect, seduced by the notion that because of their means, they will be able to control Trump. And, I imagine they are also committing another cardinal error: deluding themselves that he will not do what he says or promises. That has not been the modus operandi of authoritarians over the centuries.

—and say, well! Therefore! Obviously! California Forever, which Moritz has invested in, is a project devoted to high-minded causes like Literature, Public Services, Ending Homelessness, and Saving Democracy! But I wouldn’t have any evidence explicitly linking Crankstart’s charitable priorities to the priorities of the California Forever project…

Maybe I’m being pedantic. But I really do think that, to understand California Forever, we should start by looking at what the people involved have actually stated, and what documents like this 88-page ballot measure are actually proposing. My own read of the project is that the CEO of California Forever has no understanding of the democratic process and how important it is to win voters over, instead of buying them off. It’s easy to find quotes to support this. But the project itself seems to have genuinely earnest aspirations—everything in the 88-page PDF is exactly the kind of thing that Transit Guys and Train Guys on Twitter are asking for all the time!

Alternatively, maybe I’m being pedantic and naive. Maybe Duran is right, and this whole thing is an expertly veiled attempt to create a Srinivasan-style network state! But I am generally against this kind of anticipatory, unsubstantiated paranoia. In my essay on conspiracy theories and the internet novel, published earlier this year, I wrote about this tendency to showcase one’s politics through being

convinced [that] there was always something wrong under the surface. Being surprised was a failure of ethics, epistemology, and above all, style: it’s cringe to be caught off-guard by evil.

Personally, I’d rather be cringe than make a textually unsubstantiated argument.

If you want to read more about San Francisco politics, try—

Five recent favorites

Brief reviews of videogames-as-art ✦✧ In defense of Le Corbusier ✦✧ In defense of Robert Moses, kind of ✦✧ Why write about books? ✦✧ Why write at all?

Brief reviews of videogames-as-art ✦

Tiffany Funk’s brief history of videogames and fine art, published in ArtReview this March, describes the videogames that have been featured in esteemed art institutions like Artforum (the magazine), the Serpentine (gallery in London), and various biennials and museums. Funk also writes about indie galleries and festivals—such as Babycastles in NYC—to draw an efficient picture of where videogame art is happening, and some of the key problems of the genre.

There’s a lot of good videogame writing on ArtReview, actually—like the culture and technology writer Lewis Gordon’s 2022 review of 3 games, set in space, that reflect on economic precarity. I’m quite charmed by the description of this game:

Even amid its cosmic dystopia, Citizen Sleeper strikes a defiant, hopeful tone. It lets you forage for mushrooms (matsutake and more) – an increasingly popular metaphor for resilience amidst societal ruin (galactic or earthly) – all while focusing on further small moments of respite from oppression (you may take a break from more pressing tasks to eat a bowl of steaming hot ramen, for example).

In defense of Le Corbusier ✦

James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State is aggressively critical of the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who Scott accuses of having a “love (mania?) for simple, repetitive lines and [a] horror of complexity.” Scott sees Le Corbusier’s approach as authoritarian, inhumane, and geometrically rational to the point of actual irrationality. But let’s complicate this depiction of Le Corbusier a bit. The writer Sam Kriss’s post on Chandigarh, India shows what Le Corbusier could do when given (almost) full control over a city’s architecture and layout. “It’s nice here,” Kriss writes, “overwhelmingly nice.”

In defense of Robert Moses, kind of ✦

While we’re rehabilitating the typical villains of 20th century architecture and urbanism—the journalist and novelist Ross Barkan defends the complicated legacy of Robert Moses, the urban planner that shaped NYC and influenced many other urban planners in America:

Why write about books? ✦

One of my favorite old-fashioned blogs is Mandy Brown’s A Working Library. Brown cofounded and was previously editor-in-chief of A Book Apart, which published some of the most influential books on web design, development and culture in the last few decades.

In a recent post, “Coming home,” Brown reflects on “the restlessness inherent to screens” and how writing—especially on your own website—can combat the drifting, disembodied distractedness of social media.

I made a decision many years ago to shape my work around the books I read. If I’m being completely honest, I don’t recall spending a lot of time thinking about that decision or contemplating the consequences of it. It seemed right and so I ran with it. But it has since given rise to a kind of scholarship and writing that I’m not sure I would have landed on were I writing on some all-purpose platform, or fitting my work into someone else’s box. It’s allowed me to cultivate the soil to suit my purposes—rather than having to adapt my garden to the soil I was given. Not every seed I’ve planted has thrived, of course. But after all these years, some are quite hardy, while others have made some very rich compost. And I find myself often amazed by what emerges: not only the seeds I planted but a great many I never anticipated, connections and stories I didn’t see until I was right on top of them, until they were tangled at my feet. Dark velvety leaves amid glossy blooms, thorns and small sour fruits, vines that weave and climb and show me the way.

Why write at all? ✦

You may know kate wagner for McMansion Hell, the well-known tumblr that documented the ugliness of certain American suburban homes. She’s also the architecture critic for The Nation, and also has an excellent Substack, the late review, which focuses on “things that are not new, not generating any buzz, and perhaps are even, I dare to say, old.”

Why review old things? “Writers,” Wagner observes,

work in an atmosphere held hostage by a cycle of trends. Most publications are, due to the digital revenue model, dependent on immediacy and relevancy above all…It’s always bothered me how there is little appetite for non-longform writing about the old outside of anniversaries, retrospectives, obituaries, or unexpected revivals.

I’m always excited to read Wagner’s writing, and her latest post on writing as practice and “the right to be untalented” is especially good:

The prevailing capitalist idea that all writing has to have a ready-made audience, that it must be immediately polished, good, complete, innovative, and salable is antithetical to practice and therefore antithetical to writing…in our results-driven world, there is an aversion to practice which is ugly (to outsiders) and generally unprofitable and therefore unnecessary. Generally speaking, we have lost respect for how much time something takes. In our impatient and thus increasingly plagiarized society, practice is daunting. It is seen as prerequisite, a kind of pointless suffering you have to endure before Being Good At Something and Therefore an Artist instead of the very marrow of what it means to do anything, inextricable from the human task of creation, no matter one’s level of skill.

Many words have been spilled about the inherent humanity evident in artistic merit and talent; far fewer words have been spilled on something even more human: not being very good at something, but wanting to do it anyway, and thus working to get better. To persevere in sucking at something is just as noble as winning the Man Booker. It is self-effacing, humbling, frustrating, but also pleasurable in its own right because, well, you are doing the thing you want to do. You want to make something, you want to be creative, you have a vision and have to try and get to the point where it can be feasibly executed. Sometimes this takes a few years and sometimes it takes an entire lifetime, which should be an exciting rather than a devastating thought because there is a redemptive truth in practice — it only moves in one direction, which is forward. There is no final skill, no true perfection.

Thank you, as always, for reading. Share this post with someone you know who loves videogames, art, and doing things badly (as long as it’s fun!)

As one McLuhan blogger notes, the quote does not appear in any of McLuhan’s books or articles. It seems to come, instead, from an article about McLuhan written by the communications professor John Culkin, published in the Saturday Review in 1967.

My pitch was accepted on July 11; a week later, on July 19, Scott passed away. The obituaries and essays that followed, describing his intellectual influence and key ideas, turned out to be very helpful for my essay.

I love this essay for how chock-full it is of information, ideas and behind-the-scenes looks. The review in LARB is leaner and it successfully hits the points it meant to; I got a review of Building SimCity (which I might not have considered reading otherwise because I don't play video games), an understanding of what it provides in contrast to Nelson's game and how the California Forever project (an ostentatious name, btw) validates and connects to SimCity's popularity.

I found it interesting how building a simulation game has the collectivist spirit of what actually happens in Nelson's game, but the end result is the the fantasy of absolute, individual control in influencing and designing something as big and complex as a city. Businesses sell to individuals, but here it popped out more, probably because the self-as-god theme was a major focus.

Looking at the document list in Zotera here, I have to ask: How do you find time to read so much and ensure you don't develop only a surface-level understanding of it? Since you had a specific aim with the articles, I imagine reading and mining them for interesting, thought-provoking bits would be easier. But, I am still curious to know how you manage to read so widely especially with a day job. (This is also in light of your recent post where iirc you read 11 books in a month)

Thank you for going in such detail about your review here. It's always cerebrally pleasurable to read what you write.

Celine, I found this so fascinating, thank you! You're consistently writing some of the most interesting, well-researched essays on here -- I appreciate it! (And I just saw on a previous post you're reading Lies and Sorcery, which took me the better part of a month (maybe more?) earlier this year but changed my life a little bit!)