research as leisure activity

my favorite form of entertainment is downloading PDFs ✦ plus favorite Fluxus artists and early programs

A few years ago, I came across a particularly evocative description of the website Are.na. I’ll describe Are.na in the plainest possible fashion first: it’s a website where you can privately or collaboratively save images, text, PDFs, website links, and more into “channels.” It’s kind of like Pinterest for artists, researchers, and academics. This is a useful description, but not a beautiful one. The beautiful description was written by the librarian Karly Wildenhaus, who described it as: “Research as leisure activity.”

Wildenhaus’s description has stayed with me because it reflects how the best software products aren’t just assemblages of functionality, exposed by particular formal elements (links, buttons, icons, menus). Rather, they organize and shape how you think, and they create or sustain a particular lifestyle:

How you think: In 1985, the writer and critic Howard Rheingold published Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology, which sought to give a brief history of “the idea that people could use computers to amplify thought and communication, as tools for intellectual work and social activity.”

How you live: Earlier this year, Daisy Alioto wrote in Dirt about software as a lifestyle brand, though the emphasis is more on what the software looks like and how it’s marketed.

But this isn’t really about the software. It’s about what software promises us—that it will help us become who we want to be, living the lives we find most meaningful and fulfilling. The idea of research as leisure activity has stayed with me because it seems to describe a kind of intellectual inquiry that comes from idiosyncratic passion and interest. It’s not about the formal credentials. It’s fundamentally about play. It seems to describe a life where it’s just fun to be reading, learning, writing, and collaborating on ideas.

What does it mean to do research?

When I went to grad school in history, I actually understood very little about what research was. What I knew about research was defined primarily by scientific research, not arts and humanities research. In grad school I discovered that I loved research—I loved reading it, I loved digging through JSTOR for PDFs, I loved going to the Works Cited section of a paper or monograph and picking what to read next, I loved excavating references from the footnotes.

And I loved trying to produce research, too, in my own humble way. So here’s my broad, somewhat amateurish definition of what research is—a definition that hopefully applies across disciplines and concerns:

Research begins with a desire to ask and answer questions, thereby contributing to the greater sum of human knowledge and culture. Research often involves some hypothesis, question, or avenue of inquiry. Why is this plant a particular color? Why is this plant species a different color in different soil conditions or ecosystems? How is this color understood aesthetically and linguistically across different cultures? How can this color be recreated with artificial or natural ingredients? Does exposure to this color produce particular affective or psychological experiences for people?

Research requires commitment to evidence, broadly defined. In the sciences, this might involve running experiments and quantitatively analyzing the results; in the humanities, this might involve translating or transcribing primary sources and qualitatively interrogating them. (But this is oversimplifying things: the “sciences” and the “humanities” can overlap considerably; scientists may use qualitative analysis; humanists may use quantitative analysis.) The important thing is that there’s a commitment to some concept of truth and accuracy; there’s also a recognition of how partial and circumscribed truth and accuracy can be. That’s why scientists include error bars and qualify their results

Research requires understanding the history, theory, and practices of the discipline(s) you work within. Each discipline has its own particular history, and contemporary researchers are often elaborating upon, responding to, and reacting against that history. Anthropologists today, for example, are often trying to address the harms caused by earlier anthropologists, who contributed to European colonial and imperial projects, including the depiction of non-white, non-European cultures as racially lesser and intellectually inferior. There are also particular theoretical ideas, prior art, and specific practices that researchers need a working knowledge of. Concretely: researchers need to do a literature review that is simultaneously comprehensive and specific, that helps situate them in existing bodies of knowledge.

Research culminates in some output. Research isn’t just about collecting references and evidence and the ideas of other people. It isn’t even about synthesizing them in an interesting way. Research is about advancing new arguments and ideas in some form—typically a conference presentation, paper, book, etc.

Research ideally has contemporary relevance, but should not exclusively devoted to contemporary concerns. This might be the most controversial item on the list. I’m convinced that research should respond in some way to matters of urgent concern today (How should AI affect labor rights and economic policy? What does a world that addresses racial inequality look like? What are we going to do about the climate crisis?)…but at the same time, it shouldn’t be so narrowly instrumentalized in solving problems. There’s value in basic research that seems to have no immediate relevance to society, but can be useful later. A useful example is Katalin Karikó’s research into mRNA vaccines, which was considered useless for decades before suddenly becoming useful for COVID19 vaccine development. (For more, read Wired’s article “How mRNA went from a scientific backwater to a pandemic crusher.”)

Research is strengthened by a social and intellectual community. It typically requires mentors, peers, and mentees whose ideas and perspectives bring new energy and perspectives into the research project.

What does doing research for leisure mean?

Research is conventionally understood as occurring within academia—and potentially in government or corporate research labs, think tanks, and similar institutions. But the phrase “research as leisure activity” suggests, for me, a form of research that is explicitly not isolated to traditional institutions.

Research as a leisure activity includes the qualities I described above: a desire to ask and answer questions, a commitment to evidence, an understanding of what already exists, an output, a certain degree of contemporary relevance, and a community. But it also involves the following qualities:

Research as leisure activity is directed by passions and instincts. It’s fundamentally very personal: What are you interested in now? It’s fine, and maybe even better, if the topic isn’t explicitly intellectual or academic in nature. And if one topic leads you to another topic that seems totally unrelated, that’s something to get excited about—not fearful of. It’s a style of research that is well-suited for people okay with being dilettantes, who are comfortable with an idiosyncratic, non-comprehensive education in a particular domain.

As a result, research as leisure activity is exuberantly undisciplined or antidisciplinary. In academia, you receive specific training in a narrow field of specialization, which creates certain opportunities for your work and forecloses others. Most notably, it discourages a certain form of dilettantism—peering into an adjacent field that you don’t have the “right” background for, using techniques you aren’t “qualified” to be doing, introducing references and sources that are nontraditional and even looked down upon in your primary field. Research as a leisure activity isn’t constrained by these disciplinary fiefdoms and schisms. Any discipline can offer interesting ideas, tools, techniques.

Research as leisure activity involves as much rigor as necessary. In this style of research, certain academic practices—like extensively footnoting a written work, getting IRB approval before surveying actual people—can be ignored. This might make research as a leisure activity less rigorous and “scientific”…though Adam Mastroianni, in his post “An invitation to a secret society,” offers a few arguments for why professional science is also limited, and sometimes (often?) produces unrigorous research as well.

Who is doing this kind of research as leisure activity? Artists, often. To return to the site that originally inspired this post—I’d say that the artist/designer/educator Laurel Schwulst uses Are.na to develop and refine particular themes, directions, topics of inquiry…some of which become artworks or essays or classes that she teaches.

People who read widely and attentively—and then publish the results of their reading—are also arguably performing research as a leisure activity. Maria Popova, who started writing a blog in 2006—now called The Marginalian—which collects her reading across literature, philosophy, psychology, the sciences. Her blog feels like leisurely research, to me, because it’s an accumulation of curious, semi-directed reading, which over time build up into a dense network of references and ideas—supported by previous reading, and enriched by her own commentary and links to similar ideas by other thinkers.

There are also people who are para-academic researchers. While there’s a lot of great computer science and human-computer interaction research happening in academia, I’ve often been disappointed by some of the actual interfaces being produced by the ivory tower. Some of the most interesting work seems to be happening outside academia. There’s Geoffrey Litt, whose independent research lab publishes well-researched, thoughtful online articles about computing, software, and interfaces. And Andy Matuschak is an interesting example; he’s an independent researcher who solicits community funding through Patreon to conduct research on novel user interfaces.

I’d also say that pretty much every writer, essayist, “cultural critic,” etc—especially someone who’s writing more as a vocation than a profession—has research as their leisure activity. What they do for pleasure (reading books, seeing films, listening to music) shades naturally and inevitably into what they want to write about, and the things they consume for leisure end up incorporated into some written work.

On the decidedly informal and amateur end (I use the term amateur lovingly and respectfully!)…I’d also say that the best content on the internet is created by people who have turned research into their leisure activity. When I was a young teenager on tumblr, basically everyone I followed and looked up to adhered to the following archetypes:

A woman who just wanted to buy a bra and ended up becoming an expert on Edwardian corsetry (and, by extension, early 20th century sartorial techniques, the labor struggles of the English garment industry, and all kinds of vaguely related topics)

Someone who started off posting scans of obscure Japanese fashion magazines and ended up, essentially, becoming an amateur archivist of 1990s fashion editorials that are exclusively preserved on an obscure tumblr or Livejournal

I truly think that autodidacts are responsible for all that is good and great about alternative culture. (Or, in the discourse of our times, people with “autistic special interests”—but I kind of hate this term, as it implies that the desire to autodidactically develop expertise in a field and share it with others is an unusual desire, instead of a deeply human one…and it seems part of a broader cultural trend to restrict and even pathologize fairly common human experiences into discrete identity categories…but I digress!)

What’s also striking to me is that autodidacts often begin with some very tiny topic, and through researching that topic, they end up telescoping out into bigger-picture concerns. When research is your leisure activity, you’ll end up making connections between your existing interests and new ideas or topics. Everything gets pulled into the orbit of your intellectual curiosity. You can go deeper and deeper into a narrow topic, one that seems fascinatingly trivial and end up learning about the big topics: gender, culture, economics, nationalism, colonialism. It’s why fashion writers end up writing about the history of gender identity (through writing about masculine/feminine clothing) and cross-cultural exchange (through writing about cultural appropriation and styles borrowed from other times and places) and historical trade networks (through writing about where textiles come from).

I find myself turning this phrase—research as leisure activity—over and over again, especially as I plan out what I want to read this summer, what I want to write, and who I want to be at the end of the season.

There’s something deeply compelling to me about the idea that research—in some form—can be done by anyone with a serious commitment to intellectual inquiry.

I’ll write more in future posts about what I’m researching, I think, but for now: If you have your own leisurely research project or practice, I’d love to hear about it! Especially if there is some convergence between what I write about here and what you’re thinking about. Any of the usual methods of reaching out will do—replying to this email, DMing me on Substack, DMing me on Twitter…

If you found my Substack through this post—welcome! I write weekly-ish posts about intellectual/creative work, literature, design, art, philosophy, and technology. If you enjoyed reading this, you might also like:

Five recent favorites

Mieko Shiomi’s event poems as programs ✦✧ The Fluxus artists Nam June Paik and Alison Knowles ✦✧ Meghan O’Gieblyn on statistically startling coincidences ✦✧ Lauren Berlant on “women’s culture” and narratives of identity

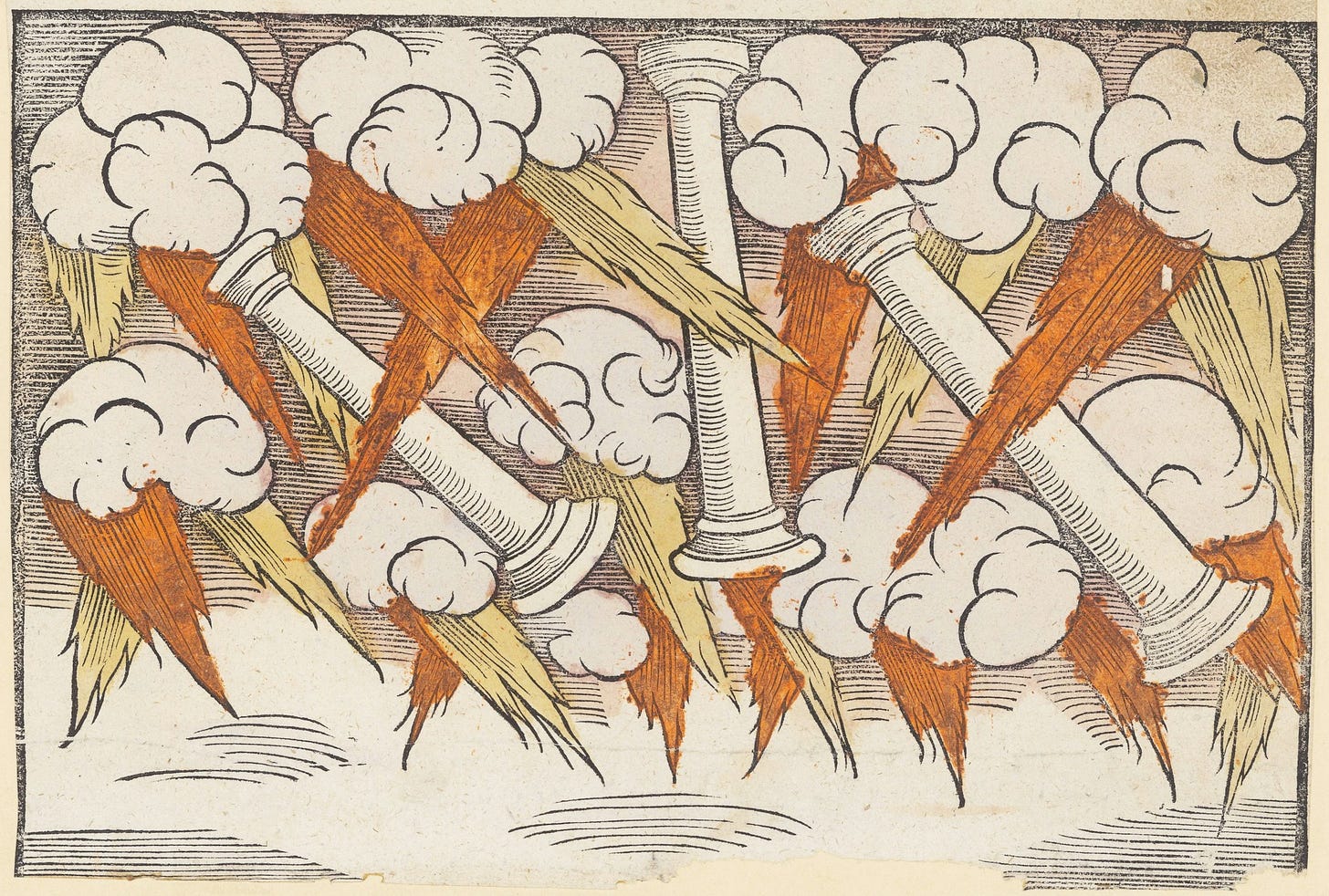

Mieko Shiomi’s Event for Midday in the Sunlight (1963) ✦

I’ve become obsessed with the artist and composer Mieko Shiomi (1938–), a key figure in Japanese postwar experimental music and in the international art movement Fluxus.

Shiomi founded the avant-garde Group Ongaku while studying musicology in Japan, which experimented with, as Connor Watson writes, “unorthodox sounds generally considered non-musical…[from] everyday objects like a vacuum cleaner.” She became interested in writing “action poems” that used verbal instructions instead of conventional musical notation, and “spatial poems” that invited others to respond to a particular instruction. She lived in NYC for about 2 years, on a tourist visa, collaborating closely with other Fluxus artists.

Here’s one of her poems, Event for the Midday in the Sunlight. What’s striking to me about these poems is that they feel a bit like an computer program—they propose a sequence of operations that can be performed on different '“hardware” (by different people). In that way, the piece is portable and can be re-enacted (re-run?) in different contexts.

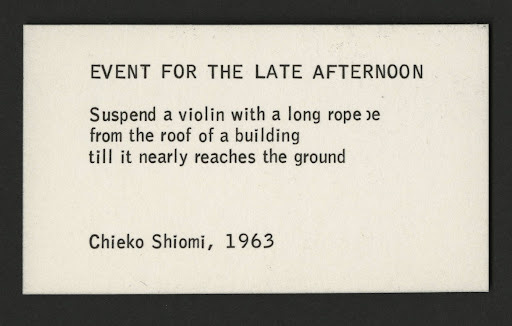

Other poems by Shiomi have been collected in a card deck of “21 Flux Events,” and low-resolution images of it are available here. One of my favorites is:

The art historian Sally Kawamura has an essay, “Towards Infinity: Mieko Shiomi’s ‘Transmedia’” that describes a performance of Event for the Late Afternoon:

Shiomi’s performance of…Event for the Late Afternoon (1963) which instructs, “Hang down a violin with a long rope till nearly the ground from the roof of a building” was performed from the roof of Okayama Cultural Centre, Japan, in 1964, and photographed by Minoru Hirata. The striking photograph, powerful in black and white, conveys an immediate awareness of height and sense of the violin floating in space. Looking at it, we can imagine the tentative manner in which the violin would have to be lowered so as not to damage it against the side of a building, and how the wind might create sound against the wood or the strings…the title was given because [Shiomi] was thinking of the pleasing way in which the afternoon light would match the orange tone of the violin.

Other favorite Fluxus artists: Nam June Paik and Allison Knowles ✦

For anyone interested in computational art and design, Fluxus is one of the most interesting artistic movements of the 20th century. (The other one, I’d argue, is the Oulipo movement, which included mostly French writers and mathematicians.)

One of the most well-known Fluxus artists is Nam June Paik (1932–2006), a Korean media artist known for his TV Buddha sculptures:

And ever since my Banff residency in 2022, I’ve been obsessed with Alison Knowles, a founding member of Fluxus who also collaborated with John Cage and Marcel Duchamp. One of the residency mentors introduced us to Knowles’s work House of Dust (1967), which is one of the earliest and most well-known works of computational poetry. The work generates poems within a certain structure (A house of…in/under…using…inhabited by…) through a FORTRAN program created by Knowles’s collaborator James Tenney.

Knowles also developed the idea of “event scores,” which:

involve simple actions, ideas, and objects from everyday life recontexualized as performance. Event [s]cores are texts that can be seen as proposal pieces or instructions for actions…Like a musical score, [they] can be realized by artists other than the original creator and are open to variation and interpretation.

Her most famous event score, Make a Salad, was first performed at the ICA London in 1962, and most recently performed at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) in 2023, as part of a retrospective on her work.

There’s a lovely New York Times interview with her, “When Making a Salad Felt Radical,” which discusses Knowles’s approach to participatory artwork:

JKA lot of your work is participatory to the point of being generous: Art is something you give to people.

AKI like that very much. I want my work to expand the terms of engagement. I don’t want people looking passively at my work but actively participating by touching, eating, following an instruction about listening, physically making or taking something, or joining in an activity.

Meghan O’Gieblyn on the startling coincidences of our lives ✦

I’m taking a writing workshop this summer with the renowned writer and essayist Meghan O’Gieblyn. Her second book, God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning, is a remarkable book about O’Gieblyn’s early life in an evangelical Christian family and theological studies—and how, after a crisis of faith, she became interested in technology and transhumanism, and the ways in which technologists have reinterpreted spiritual and theological questions into AI and existential risk ones.

There’s one particular passage in the book I was quite struck by—where O’Gieblyn writes about our tendency to draw out patterns from the world, extracting from the random stimulus of the world some sense of coincidence and synchronicity:

Our brains have evolved to detect patterns and attribute significance to events that are entirely random, imagining signal where there is mostly noise. This tendency is probably hypertrophied in writers, who are constantly seeing the world in terms of narrative. In fact, for a while, encountering this very sentiment in books became yet another doubling in my life. “When I am absorbed in writing a novel, reality starts twisting to reflect and inform everything I’ve been thinking about in my work,” Ottessa Moshfegh notes in an essay. Virginia Woolf, writing in her diary in 1933, expressed essentially the same thing: “What an odd coincidence! that real life should provide precisely the situation I am writing about!” The novelist Kate Zambreno claims that when she is working, she often sees the same names and the same books everywhere: “I begin to make connections with everything—I see literature everywhere, a vast referentiality.”

I felt this very strongly while reading O’Gieblyn’s book. Before starting it, I’d decided to read more Kierkegaard this summer, and discussed this extensively with my girlfriend—who has been reading The Brothers Karamazov and keeping me updated on the adventures of Mitya, Ivan, and Alexei.

It turns out that God, Human, Animal, Machine discusses both Kierkegaard and The Brothers Karamazov—which felt like a surreal, even spiritual coincidence…even though both are part of the Western philosophical and literary canon, and it’s not that unlikely that an author I’m reading would be reading and referencing both. Or maybe it is unlikely? Maybe it’s a sign?

O’Gieblyn also references a thinker I’m very unfamiliar with, Giorgio Agamben…and two days after finishing the book, I was listening to a podcast episode (more on this below) which referenced a Lauren Berlant book, and when I started reading a copy of it, I found that Berlant had listed a long list of their influences, including…Giorgio Agamben. Again, it’s hard not to feel like there is something out there telling me to read Agamben and make use of his ideas! His name seems to be showing up everywhere; it seems like such coincidences must be meaningful, even though they could easily be statistically predictable noise.

Lauren Berlant on “women’s culture” and narratives of identity ✦

I keep on insisting that I am “not a podcast person” whenever someone tries to recommend me a podcast. This is largely true, but I am a huge Merve Emre stan—so I’ve been devouring her podcast The Critic and Her Publics, which features writers like Andrea Long Chu and Moira Donegan.

The latest episode features Lauren Michele Jackson, who coined the term “digital blackface” in a 2017 article for Teen Vogue, and later wrote a critique of the anti-racist reading list (“What Is an Anti-Racist Reading List For?”) in June 2020 for Vulture.

In the episode, Jackson mentions a Lauren Berlant book I hadn’t heard of before, The Female Complaint, which analyzes how pop culture has created an “intimate public” of women based on the assumption of a shared, universal experience of womanhood. As Berlant writes in the introduction:

In the contemporary consumer public…all sorts of narratives are read as autobiographies of collective experience…[There is] is an expectation that the consumers of its particular stuff already share a worldview and emotional knowledge that they have derived from a broadly common historical experience. A certain circularity structures an intimate public, therefore: its consumer participants are perceived to be marked by a commonly lived history; its narratives and things are deemed expressive of that history while also shaping its conventions of belonging; and, expressing the sensational, embodied experience of living as a certain kind of being in the world, it promises also to provide a better experience of social belonging—partly through participation in the relevant commodity culture, and partly because of its revelations about how people can live.

I experienced a certain shock of clarity and recognition reading Berlant’s words. I’ve been quietly, subconsciously troubled for some time at how much media I consume presumes a kind of universal “feminine” experience, or universal “queer” or “Asian American” or even “queer Asian American woman” experience that is just not true in my specific, individual life. But the presumption of universality is there! Which isn’t to say that I reject all of this, and feel alienated by this—but it’s an interesting phenomenon, one that Berlant dissects almost perfectly in their 2008 book:

Whether linked to women or other nondominant people, it flourishes as a porous, affective scene of identification among strangers that promises a certain experience of belonging and provides a complex of consolation, confirmation, discipline, and discussion about how to live as an x. One may have chosen freely to identify as an x; one may be marked by traditional taxonomies—those details matter, but not to the general operation of the public sense that some qualities or experience are held in common. The intimate public provides anchors for realistic, critical assessment of the way things are and provides material that foments enduring, resisting, overcoming, and enjoying being an x.

Thank you, once again, for reading this newsletter! I’m coming up on my six-month anniversary of writing here soon (on June 9…13 days from now!) and it’s been genuinely so fun and intellectually activating. Until next time—

To say I loved this essay is an understatement. This spoke to me on so many levels. I have been sitting on a draft of a post I wrote a while back all about my love for all forms of research and how each day I wish my life was full of it. The words “research as leisure activity” sums up my life’s biggest goal. To spend as much time of my limited time on this earth (4,000 weeks average lifespan) doing research as a leisure activity. Research and leisure are two of my most important values, combine them together and I am at my happiest. Sorry if this doesn’t make sense, I’m writing this at the end of a long day. I love downloading PDFs as well!

Another timely one from you! I've been reading on Niklas Luhmann's Zettelkasten note-taking system, in an attempt to develop a personal research system that allows me to read more leisurely, sans the anxiety of feeling like I have to turn everything I consume into some sort of essay 😅

Also: "it seems part of a broader cultural trend to restrict and even pathologize fairly common human experiences into discrete identity categories…" MHMM YES