what's the point of representation in art?

on bell hooks, Kerry James Marshall, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye ✦ and the politics of Black figurative painting and the artistic canon

Has anyone else noticed how the sharpest social critics of our time end up blunted by the internet? I’ll often see someone quoted (and subsequently retweeted, reblogged, reposted) for the most consumable, most easily metabolized parts of their books. But to find the parts that challenge and unsettle me, I usually have to go straight to the source.

Last year, this happened with bell hooks. A screenshot of a quote from her essay “Women Artists: The Creative Process” made the rounds on Twitter. Taken out of context, it reads as an uncomplicated appreciation of leisure and luxury:

But the context of the essay, and where it’s situated in her book Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, completely changed how I read this paragraph. It appears right after a chapter where hooks describes how a childhood “longing to cultivate my own style and taste” conflicted with her adolescent-to-adult awareness that certain objects, “considered luxurious…[were] desired because the culture of consumerism had deemed them lovely symbols of power and possibility.”

Five pages later, hooks is describing the “luxurious smells of expensive French lemon verbena soap”. But she’s doing so with a certain ambivalence. The overall essay is less about luxurious objects, and more about the luxury of time—and how necessary it is for one’s artistic practice. The essay is about the solitude and undisturbed space needed to be an artist and writer. And the difficulty, sometimes impossibility, of doing so when you have to work for a living, and when other demands (especially domestic demands, for women) intervene. The luxury that matters is the time that she can devote to “artistic self-actualization.”

Black painting and the artistic canon

When hooks wrote Art on My Mind in 1995, she was responding to a “dearth of progressive critical writing” on art and aesthetics, and the visual politics of how artists are canonized or marginalized. The introduction to the book—subtle, deliberate, powerful—describes hooks’s relationship to canonical art and especially art by white men.

There are two easy, lazy ways that people approach about the canon, and hooks avoids both. Those two ways are:

Rejecting it entirely (for being dominated by privileged white men, and therefore inherently limited), and refusing to take anything from it, encounter it seriously, and be transformed by it

Embracing it uncritically (as an uncontested and “objective” list of great art), and becoming confined to a parochial and limited subset of cultural works, while being totally convinced that there is nothing else that is good enough and worthy of attention

Instead, here’s how bell hooks approaches the canon. She begins by discussing abstract expressionism, that great American art movement that elevated a whole pantheon of white men (including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning) to the canon:

Art has no race or gender. Art, and most especially painting, was for me a realm where every imposed boundary could be transgressed. It was the free world of color where all was possible…

My pleasure in abstract expressionism has not diminished over the years. It has not been changed by critical awareness of race, gender, and class. At times that pleasure is disrupted when I see that individual white men who entered the art world as rebels have been canonized in such a way that their standards and aesthetic visions are used instrumentally to devalue the works of new rebels in the art world, especially artists from marginal groups.

Most black artists I know—myself included—have passionately engaged the work of individual white male artists deemed great by the mainstream art world. That engagement happens because the work of these artists has moved us in some way. In our lived experience we have not found it problematic to embrace such work wholeheartedly, and to simultaneously subject to rigorous critique the institutional framework through which work by this group is more valued than that of any other group of people in this society. Sadly, conservative white artists and critics who control the cultural production of writing about art seem to have the greatest difficulty accepting that one can be critically aware of visual politics—the way race, gender, and class shape art practices (who makes art, how it sells, who values it, who writes about it)—without abandoning a fierce commitment to aesthetics..

I’ve bolded the part that moves me the most—where hooks advocates for a genuine appreciation and pleasure in these works, without sacrificing a keen political analysis of why these works are known to everyone, while other works are ignored.

But hooks was writing this in 1995. Reading it now, I’m struck by how different contemporary art has become in the last three decades, and especially how different contemporary painting is from the world she describes. Today, abstract expressionism is treated with distant reverence. Artists like Willem de Kooning, Pollock, and their peers feel like artistic ancestors, lingering on in art history books.

What kind of painting is happening today? Figurative painting. And what’s in vogue is Black artists painting Black figures in portraits that recall the typically “canonical”, typically revered paintings of great European art. One of the best examples of this is Kerry James Marshall’s work, which often features Black people arranged in stately, nearly aristocratic poses:

The New Yorker’s profile of Kerry James Marshall describes how Marshall arrived at this style of work. I’ll summarize some of the biographical details in the profile:

Born in 1955, in “rigidly segregated” Birmingham, AL

Family moved to Los Angeles in the 1960s, where Marshall lived for some time in a public housing project in Watts

In junior high, a teacher encouraged Marshall to take a summer drawing class at an art school that he later attended for his B.F.A. But he was disenchanted with the school’s emphasis on conceptual art: “Anything that looked like conventional painting and drawing and sculpture was dismissed,” he said to the New Yorker. “There was no rigor.”

After graduation, he abandoned abstraction for figuration, and became obsessed with Renaissance art

One of his early paintings, the 1980 Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, used an egg tempera–based paint he made using a fifteenth-century formula

In the early decades of his career, the critic Calvin Tomkins writes,

Marshall was an outlier, and happy to be one. He had an unshakable confidence in himself as an artist, and the undistracted solitude of his practice allowed him to spend most of his time in the studio.

He was successful but not widely known, until a quick succession of museum shows, starting in 2016—at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Met Museum in NYC, and then the MOCA in LA. For this retrospective, the curators initially proposed the title “Kerry James Marshall: Old Master”. Marshall changed Old Master to Mastry, which expresses both his investment in technical, art-historical mastery—and a desire to be colloquial, familiar, and playful.

Marshall has become a “primary influence” for younger Black artists who have embraced figurative painting. One of those artists is Kehinde Wiley, who painted Barack Obama’s portrait for the National Portrait Gallery. Wiley’s paintings are also inspired by canonical European painters—a 2017 painting remakes Francisco Goya’s La Lectura with Kerry James Marshall as a character. Another artist might be the British-Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose solo painting show in London was installed at the Tate Britain, not the Tate Modern—an intriguing move, since it placed Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings alongside galleries of more typically Old Art, Institutional Art, Widely Acknowledged Canonical Art.

I caught Yiadom-Boakye’s show just before leaving London last year. I went with two close friends, and we moved slowly through each room, taking in the carefully evoked contours of people’s faces, clothes, bodies, expressions. The paintings have an undeniable electricity to them—saturated, energetic colors; larger-than-life figures in intimate, familiar poses.

The most satisfying way to experience Yiadom-Boakye, in my opinion, is on a formal and aesthetic level. That’s what Zadie Smith does in her essay on the painter. She devotes herself to describing the colors, the gestures, the way the paintigns are complemented by the obliquely expressive titles that Yiadom-Boakye—a writer and painter—has chosen. And this approach matches how Yiadom-Boakye discusses her work as well; the Smith essay quotes her saying “My starting points are usually formal ones.”

But an interest in formalism, especially with figurative painting, seems to make art critics anxious. Smith gently critiques “the keenness to ascribe to black artists some generalized aim—such as the insertion of the black figure into the white canon.” The figures Yiadom-Boakye paints are more gestural, more familiar. They’re very different from the highly structured, monumental paintings that Kerry James Marshall has done. The people in Marshall’s paintings carry themselves with a regal hauteur. Yiadom-Boakye’s people stretch, lounge, slouch.

They’re both Black painters, but are they both Black painters with the same relationship to canonical portraiture? I’m not so sure about that. So where does that keenness that Smith describes—the desire to fold both into the same artistic project, the black figure into the white canon—come from? This is a narrative that is less about the artworks themselves and more about the art world. It comes from curators and critics and everyone around the painters; it comes from those who contextualize and commercialize and eventually canonize some artists but not others, some artworks but not others.

There are so many reasons—social, historical, economic, political—why Black artists were so absent in bell hooks’s artistic education, and so present now in established art institutions. But I’m quite interested in why the Black artists celebrated today for very consistent and specific reasons—for their figurative portraits of Black people—and what it says about representation politics in art.

On representation politics in painting, and deference politics in discourse

The dominance of figurative painting in contemporary art—especially painting that represents a historically marginalized group—is the topic of the art historian Larne Abse Gogarty’s “Figuring Figuration”, published in Art Monthly’s April 2023 issue. (You can find a PDF here.)

Gogarty argues that we need to ask “how and why this kind of painting has been granted primacy”, and what it says about identity politics in the art world. Sometimes, a well-meaning desire to elevate certain Black painters for their Blackness can minimize their investment in leftist political projects:

The curatorial gesture of ‘correcting the canon’ is rarely without complications or compromise. For instance, the elevation of Alice Neel and Charles White to ‘great painter’ status through major retrospectives has involved an inevitable minimising of the way their commitment to painting people was inextricable from their commitments to communism.

More cynically, the obvious presence of Black art on the walls can obscure the racial inequality elsewhere in the art world. Artists who exhibit “a politicised engagement with realism and representation…are readily welcomed by the market and arts institutions,” she notes, even when the kinds of people represented in the paintings “continue to be marginalised in the everyday workings of those establishments.”

It’s clearly of some progressive value to have Black artists taking up space, as the phrase goes, on the walls. But is this highly visible form of diversity contributing to other progressive causes? The working conditions of art workers? The ability to participate in art institutions without being wealthy? As Gogarty notes,

this isn’t an argument against representation, but a note of scepticism about what hyper-visibility in the present means, when few of the institutions organising ‘success’ have changed.

Gogarty’s argument made me want to revisit the philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else). Táíwò is one of my favorite contemporary philosophers (along with Amia Srinivasan and, controversially, Agnes Callard…) and his book is a crisp, aggressively brilliant analysis of—to put it bluntly—the numerous political failures of identity politics as practiced today.

It’s worth noting that Táíwò is not against identity politics as originally formulated by the Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist organization that was explicitly socialist and anti-imperialist. He’s against the ways in which identity politics has since been stripped of its radical potential and repurposed as a way of further entrenching elite power. “[S]ymbolic identity politics,” he writes, is often used “to pacify protestors without enacting material reforms.” Elite actors and elite institutions have no problem including a few token minorities, as a concession to a very, very long history of racial oppression and marginalization. Doing so doesn’t have to involve any real sacrifice of power, or any real commitment to changing how these institutions operate.

One of the most useful terms in Táíwò’s book is “deference politics.” If representation politics is about who creates art and culture, and who is depicted in it, then deference politics is about who creates discourse and contributes ideas. Táíwò sees deference politics as a de facto norm in politically progressive circles. But he’s critical of what deference politics does, and what it can accomplish:

A prime example of deference politics is the call to “listen to the most affected” or “center the most marginalized,” now ubiquitous in many academic and activist circles. These calls have never sat well with me. In my experience as an academic and organizer, when people have said they needed to “listen to the most affected,” it wasn’t usually because they intended to set up Skype calls to refugee camps or to collaborate with houseless people. Acting on this conception of “centering the most marginalized” would require a different approach entirely, in a world where 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing (slum conditions) and 100 million are unhoused, a full third of the human population does not have reliable drinking water, and the intersections of food, energy, and water insecurity with the climate crisis have already displaced 8.5 million people in South Asia alone, while threatening to displace tens of millions more.

Clearly, people with marginalized identites should be able to testify to their experiences, within the discursive spaces they occupy. But Táíwò sees deference politics as an approach that distracts us from actually addressing any material and political inequalities. Those inequalities become abstracted away, blunted by “intermediary goals cashed out in pedestals or symbolism.” Deference politics makes sure that, in a room of white-collar office workers, the more privileged experience an acute feeling of guilt about not centering others, and the less privilege are afforded the opportunity to speak (or, more cynically, pushed to speak to assuage everyone else’s guilt). But the world’s most marginalized people, Táíwò points out, aren’t even in the room. What world does deference politics build? It’s a world where

we seem to end up with far more, and more specific, practical advice about how to, say, allocate tasks at a committee meeting than how to keep people alive.

So where do we go from here? What do we do when the most readily available strategies for racial equity (and other forms of equity, too) have such tragic limitations?

Representation: Useful, but easily deployed to placate us, to construct aesthetic narratives in which individual artists, with their specific aims, become subsumed into some broader narrative that fits in with specific identity-political themes

Deference: Useful, but also a tactic of pacification, one that focuses on minor gestures instead of major political projects.

Where do we go from here? I sadly have no idea—this is the great problem, the great project, of politically inflected art and literature and discourse today. How can I have a practice that embodies, in overt or subtle ways, my political commitments and aspirations? How can I contribute to or cultivate a community that does the same?

But it’s an interesting project—the kind of project that can occupy a life of thinking and theorizing and criticizing and trying. So I’ll keep working on this question—of how to engage with identity/representation/action in contemporary art and life—and I’ll keep on working through it here, in public, with all of you.

Thank you, as always, for reading! And do reply to this email (or leave a comment on Substack) if you have anything to share about your own relationship to representation politics and deference politics and painting and the artistic canon.

Three favorites for Black History Month

Ishmael Reed on tokenization and literary talent ✦✧ Tressie McMillan Cottom on beauty ✦✧ Yussef Dayes’s debut album ✦✧

Ishamel Reed rails against the tokenization of Black American writers ✦

I can’t write a post about representation in art and literature without mentioning Ishmael Reed’s “On Tokens and Tokenism”. In it, Reed applies his usual incandescent forcefulness and rigor in writing about how certain Black writers become tokenized by the American literary establishment.

He discusses, for example, how Jill Biden chose Amanda Gorman to read a poem (“trite, platitudinous”) at Biden’s inauguration. But Gorman is an easy poet to pick on. Reed doesn’t stop there; he describes how tokenism shows up when obviously great writers—Ta-Nehisi Coates, James Baldwin—are treated as the only Black writers worth knowing:

I often get into arguments with liberals, Black and white, when I direct them to writers who write as well as the tokens. They are invested in the belief that because they’ve read Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963) they have Black literature covered.

Reed is arguably one of the great Black writers working today. But instead of letting himself be buried alive as a token, Reed has committed himself to raising the literary profile of other writers. “When I was groomed to be a token,” he writes, “I denounced it. So should the current tokens. By doing so, they will allow Black literature to breathe.”

I return to this essay over and over for Reed’s closing sentences, which vigorously denounce tokenization—by arguing for the sheer quantity of great writing and moving writing by unknown writers, the un-tokenized ones.

I placed my students and canonized writers in the same volume in my anthology…Professors attending a conference couldn’t tell the difference. The token-makers claim that American talent is rare, and by doing so they are depriving American readers of a rich reading experience. Based upon my experience, American talent is not rare. It’s common.

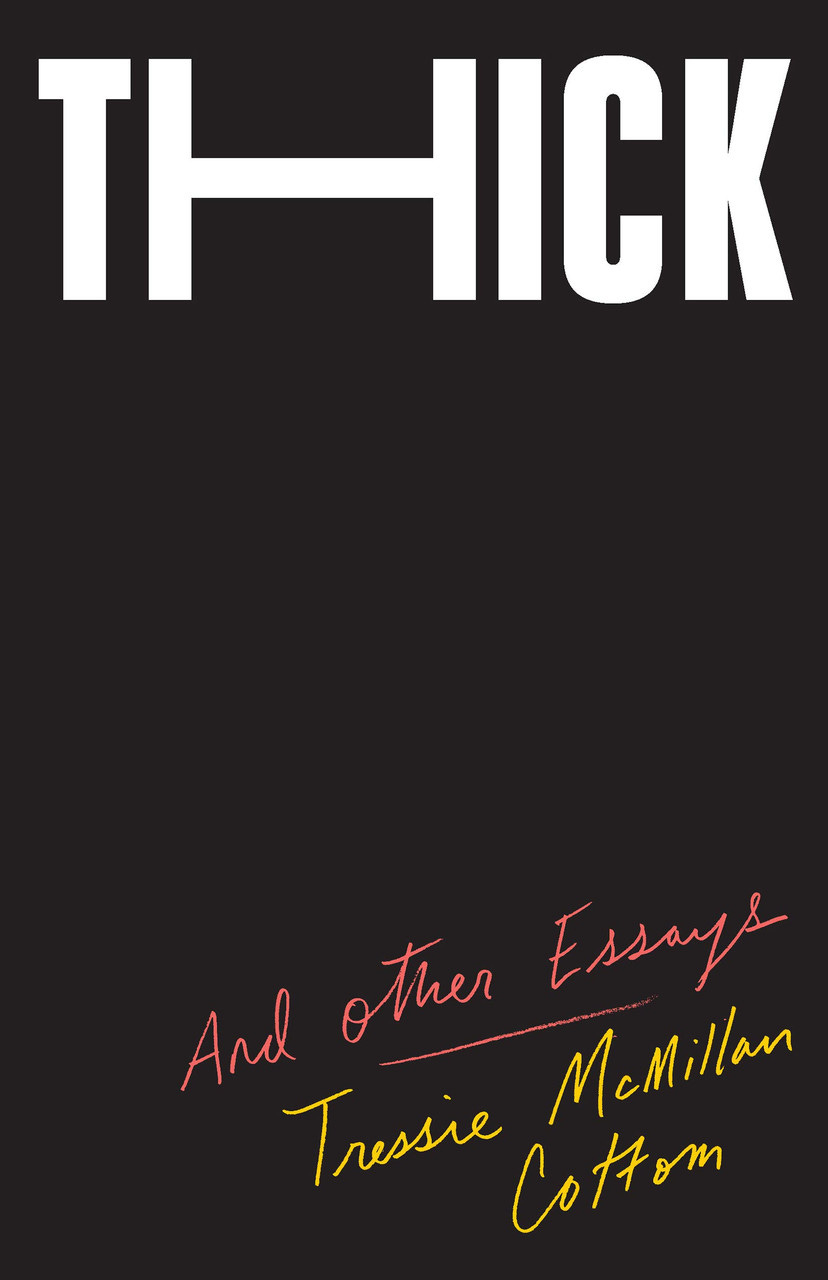

Tressie McMillan Cottom on beauty ✦

Tressie McMillan is a sociology professor, MacArthur fellow, and essayist who focuses on inequality in higher education and technology. I came across her research when I was designing for Logic—she was interviewed for issue 3, JUSTICE, the first one I helped out with!—but she’s also a brilliant and very funny social critic.

At this point I have recommended her book Thick: And Other Essays to just about everyone I know. In it, Cottom discusses racialized beauty standards, what it feels like to attain middle-class security, the banality of LinkedIn, and embarrassing Twitter follows. (“Now listen,” she writes, “nothing about Twitter is a stand-in for someone’s soul. I follow a porn anime account because sometimes they tweet really neat pictures of black cartoon characters. Only god can judge me.”)

But the best essay in Thick is “In the Name of Beauty,” which remains one of the best takes on beauty standards—what you gain from adhering to them, and what you lose in that acquiescence. Bolding mine:

Black women have worked hard to write a counternarrative of our worth in a global system where beauty is the only legitimate capital allowed women without legal, political, and economic challenge. That last bit is important. Beauty is not good capital. It compounds the oppression of gender. It constrains those who identify as women against their will. It costs money and demands money. It colonizes. It hurts. It is painful. It can never be fully satisfied. It is not useful for human flourishing. Beauty is, like all capital, merely valuable…

Beauty would not be such a useful distinction were it not for the economic and political conditions…If I believe that I can become beautiful, I become an economic subject. My desire becomes a market. And my faith becomes a salve for the white women who want to have the right politics while keeping the privilege of never having to live them. White women need me to believe I can earn beauty, because when I want what I cannot have, what they have becomes all the more valuable. I refuse them.

I love this: Cottom’s cool, unclouded assessment of why beauty is useful capital to women, why women might want to leverage it—and why we can’t accept it as uncritically good. And I love her refusal: if we know that beauty is “not useful for human flourishing,” can be we be more cynical about its pursuit?

Yussef Dayes’s Black Classical Music ✦

I wrote half of this post while listening to Yussef Dayes’s Black Classical Music. Dayes is a contemporary jazz composer living in London, and released quite a few collaborations with other musicians before his 19-track debut album was released last year.

There’s such a nice, capacious feeling of abundance in B.C.M.: energetic, resonant sounds, sliding from instrument to instrument. And because I’m still doing my anti-algorithm year of cultural consumption, I should add that I came across this album because a stranger was playing it in her car—I complimented the music, and that’s when she told me about Dayes.

A final hot take to close off this post—

Nothing, to me, exposes the intellectual and ethical illegitimacy of the men’s rights movement more than the fact that they never seem to focus on one of the greatest social injustices of our time, one that disproportionately impacts men: the systemic incarceration of Black men in America. What’s up with that? (Rhetorical question; I already know why.)

Those guys should really be reading the legal scholar and activist Michelle Alexander’s 2012 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness…but they won’t…too bad for them, and too bad for us!

love this post and recommended readings. a video and an article on black representation that stuck with me:

- bell hooks Pt 8 cultural criticism (rap music).flv on YouTube - how can we ascribe authenticity to the work of marginalized groups when mass demand in the capitalist system filters for what can succeed?

- Bertrand Cooper's "Who Actually Gets to Create Black Pop Culture?" - asks the same question, but about the supply side