oblique strategies for starting a new project

how I use Brian Eno's Oblique Strategies in writing and designing ✦ Žižek's notetaking advice

I’ve just finished two writing projects this week. The smaller one is a post about my favorite Japanese notebooks for

, a newsletter by Kyle Chayka and Nate Gallant. I really love the newsletter—it’s deeply satisfying to read if you, too, are pursuing an anti-algorithm year of cultural and material consumption.The other project is a book review that is coming out, online and in print, in early February. I’m so tremendously excited about this—more soon! But it feels strange to leave the frenetic, final editing stage behind and be, suddenly, done.

Which means it’s time to begin the next writing project. I’m once again facing the blank document, the empty page, trying to find my way into the work.

A few years ago I came across, on a relatively obscure online forum, a post where someone had asked: “Why am I incredibly passionate about learning things but dread actually putting them to use?” It was 2020; it was the first year of COVID, and I had all these insistent intellectual and artistic ambitions that weren’t going anywhere—I just couldn’t do anything with them, some project or piece.

So I was struck by this question, and especially struck by this comment:

Learning to finish is a skill in itself…being able to push through the boring, tedious, difficult (yet necessary) parts to a satisfactory conclusion without quitting.

Starting is easy. Everybody does that. Finishing is hard…it is an acquired skill but one definitely worth learning.

In the years since I read this, I realize—over and over—how true this comment is. Finishing is a skill—a skill that’s distinct from the more specific, obvious skills of writing, designing, drawing, painting, building, producing. It’s a skill that seems to envelope my experience of these other practices. Every essay I finish makes me incrementally better as a writer.

Finishing is also a skill that transfers across domains. In the last year, I’ve gotten much better at finishing design projects at my day job—and it’s somehow made me a better writer as well.

Finishing a design forces me to tidy up all the loose ends—which can be, as this internet commenter wrote, “boring, tedious, difficult (yet necessary)”. It forces me to accept certain limitations: an idea that isn’t working, a direction that felt promising but turned out to be a dead end, a detail that needs to be cut to make the whole more coherent. On Friday I looked at the 10 visual variations I’d produced for a small design detail, threw out 9 of them, refined one.1

It turns out that this practice—of cutting what isn’t working, and honing what remains—translates beautifully to writing. At the bottom of every draft I write is an area for my outtakes: the paragraphs that are beautifully written but useless to my thesis; the points I wanted to make but couldn’t land; the details that are unnecessary, even though I’m attached to them. For a 1,000 word review, I might have 2,000 words of outtakes—all the words I had to leave behind to finish a work and make it feel whole.

Finishing is a skill, and I am devoting 2024 to practicing it. Devoting my life, really, to practicing it. Finishing writing projects. Finishing design projects. Selecting some intention and executing all the way to the end.

There’s just one sentence, in the comment above, that I disagree with: “Starting is easy.” Is it? It hasn’t been—at least for me—and I am always trying to find new strategies for starting, new strategies for beginning.

Whenever I start a new project, a certain kind of empty, formless fear settles over me. The specific content of the fear depends on the medium:

If I’m writing: The fear that I have nothing to say. The fear that I will not be able to find anything to say, that there will be no argument or thesis at the core of what I’m doing. That I won’t be able to sustain the argument, over hundreds or thousands of words, in an elegant and even literary way.

If I’m designing: The fear that I cannot make something beautiful or useful. The fear that I cannot make it both beautiful and useful at once, that all I can do is uselessly generate something derivative, something that can’t possibly be useful to anyone.

These are debilitating fears; they inhibit starting, they hold me back from finishing. To face these fears, I lean on process: a loose sequence of steps I can take to go from the desire to create something to an actual work, fully elaborated and realized.

A creative process always involves some interplay between discipline and freedom. Discipline, for me, is all about structure: write the outline, write the first draft, write the second draft, and so on. I’ll simultaneously try to keep things from becoming too rigid, too determined, by inviting in more loose, exuberant ways of working.

Lately I’ve been trying to invite more randomness—and superstitiousness, even—into my process. Here’s an excerpt from my in/out list for 2024:

Astrology? Out.

Tarot? In.

The I Ching? In—although this feels ridiculous to say about a classic divination text that has been influencing human culture since the 9th century BCE!

Like all in/out lists, this says more about me than about any larger cultural trends (although I do think we have reached peak astrology). And I’m specifically obsessed with the I Ching because the second book I read this year was Geeta Dayal’s book about the ambient musician and producer Brian Eno. Dayal devotes much of the book to describing Eno’s processes for creating and collaborating on music, and reading it was an incredibly generative experience. I love reading about other people’s creative processes—it’s a great and highly instructive form of artistic voyeurism.

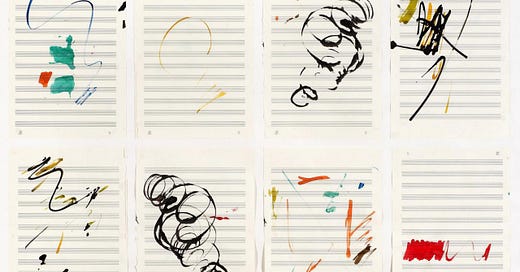

And Eno makes it especially easy to learn from his process. In 1975, he and the artist Peter Schmidt released their Oblique Strategies deck of cards, which were inspired by the I Ching—and likely inspired, too, by the American composer John Cage’s use of the I Ching for making musical decisions.

Each card contains an enigmatic, epigrammatic strategy for confronting a creative problem. The strategies are abstract enough to apply to nearly all disciplines: music, of course, but also writing and design. As Eno later said:

The Oblique Strategies evolved from me being in a number of working situations when the panic of the situation—particularly in studios—tended to make me quickly forget that there were others ways of working, and that there were tangential ways of attacking problems that were in many senses more interesting than the direct head-on approach.2

I bought an Oblique Strategies deck after reading Dayal’s book. I’m currently using it as a pseudo-tarot deck for creative projects. Instead of drawing 3 cards and performing a reading for my past, present, and future, I’ll draw 3 cards to help me start, continue, and finish a work.

For my new writing project, I drew the following cards:

A strategy for starting: Slow preparation…Fast execution

A strategy for continuing: Don’t be afraid of things because they’re easy to do

A strategy for finishing: Once the search is in progress, something will be found

I’m slowly preparing, as the cards suggested. My next project is another book review. I’ve developed a loose process for reviewing. I begin by reading the book I am reviewing. Then I read it again in order to “index” it: I’ll write down page numbers and brief descriptions (and sometime quotations) of anything especially striking, then review my notes and summarize the major themes of a work, and where those themes appear. I’d like to think this is what Frederic Jameson, the Marxist literary critic and philosopher, meant when he described his technique for taking notes:

mark everything you notice in back of book, then combine them in as many categories as you can think of.

When I’m indexing a book it always seems so unbearably slow. I begin to worry that my patient note-taking practice is actually a way for me to avoid the hard work of writing, the real work, where I am advancing actual arguments, ideas, opinions!—instead of taking my unambitious little notes.

Notetaking feels easy. I have this instinctual suspicion of the easy things: shouldn’t writing involve a little bit more effort, strain, suffering? But here’s where the strategy for continuing helps: Don’t be afraid of things because they’re easy to do. Especially when it’s notetaking—which is exceptionally valuable and productive work.

That’s the thesis of Sönke Ahrens’s How to Take Smart Notes, which argues that notetaking is foundational to the practice of writing. “Every intellectual endeavour starts with a note,” Ahrens asserts. “Good writing begins with good note-taking.”

To get a good paper written, you only have to rewrite a good draft; to get a good draft written, you only have to turn a series of notes into a continuous text. And as a series of notes is just the rearrangement of notes you already have in your slip-box, all you really have to do is have a pen in your hand when you read.

This approach makes writing seem easy. It’s not a mystical, mysterious process—it’s actually a very ordinary, straightforward one. You begin with reading, and taking notes on your reading, and assembling all the notes into a draft, and then you revise the draft into a written work.

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has a similar stance on notetaking—which I learned about via my dear friend Nat Hartman (also a designer and writer!).

If this strategy is good enough for Žižek, it’s good enough for me. Writing: it’s simply notetaking! It’s simply reading, and being interested and invested in your reading, and accumulating reflections and reactions to the reading, and then synthesizing that into a work.

I am placing my trust in the process. I am choosing to believe that working in this way will carry me through to the end of my current project. The last card from my pseudo–tarot reading is now taped to the wall above my desk: Once the search is in progress, something will be found. It’s a strategy for finishing, a strategy for trusting in my ability to complete a work.

Also! If you’re working on a project and want some oblique strategies for your work—comment on this post, or reply to my email, and I’ll do a similar 3-card draw tarot reading for you! Please note I know almost nothing about how tarot is really supposed to work, but it’s been fun…

Four favorite things

My favorite historian of technology on free will and agency ✦✧ Dream sequences in contemporary Chinese cinema ✦✧ Restaurant trends in 2024 ✦✧ …and in 1800–2000 ✦✧

James Gleick on free will and agency ✦

I loved “The Fate of Free Will,” an essay about whether free will exists or not—and the psychological, philosophical, and political consequences of how we answer this question—in the January 18 issue of the New York Review of Books.

The essay is by James Gleick, who writes tremendously beautiful, gripping, evocative, fascinating books about the history of science and technology. His 2011 book The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood was a major intellectual inspiration for me—it made information theory feel intimately connected with humanistic and cultural concerns.

I’m kind of a Gleick fangirl—and I really, really liked his latest NYRB essay, where he describes the near-consensus opinion in neuroscience and philosophy about how free will doesn’t really exist. Gleick efficiently summarizes how this consensus developed, and the insidious implications of it:

[T]he conviction that we act with some degree of freedom features not just in our private thoughts but in our public life. Legal institutions, theories of government, and economic systems are built on the assumption that humans make choices and strive to influence the choices of others. Without some kind of free will, politics has no point. Nor does sports. Or anything, really…

If the denial of free will has been an error, it has not been a harmless one. Its message is grim and etiolating. It drains purpose and dignity from our sense of ourselves and, for that matter, of our fellow living creatures. It releases us from responsibility and treats us as passive objects, like billiard balls or falling leaves.

To me, the essay advocates for a more refined understanding of free will—moving away from the biological reductionism that denies the existence of free will, and perhaps using the term agency to reflect the conscious choices and ethical implications of our actions.

Bi Gan’s dreamlike film about love, memory, and loss ✦

On Monday I caught a showing of the Chinese director Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018/9). It’s a strange, beautiful film about a man, Luo Hongwu, and his passionate, complicated (cinematic relationships are always complicated!) relationship with a woman who later disappears from his life.

The first half of the film, traditionally shot in 2D, is a nonlinear retelling of their relationship: illicit meetings in a strange abandoned building, intense and nearly violent encounters on a train, the woman suggesting that she’ll leave her boyfriend (who seems to be some kind of gang leader?) for Luo, and her eventual disappearance.

The second half is technically and aesthetically quite remarkable: it’s an unbroken, 59 minute shot with subtle 3D effects. I generally find 3D films very—cheesy? they feel like tech demos more than anything—but the way Bi Gan uses 3D here is so intriguing and works perfectly with the film’s narrative style.

In an interview, Gan said:

It's a film about memory. After the first part (in 2D), I wanted the film to take on a different texture. In fact, for me, 3D is simply a texture. Like a mirror that turns our memories into tactile sensations. It's just a three-dimensional representation of space. But I believe this three-dimensional feeling recalls that of our recollections of the past. Much more than 2D, anyway. 3D images are fake but they resemble our memories much more closely.3

Restaurant menu trends in 2024 ✦

I loved this New York Times article, “The Menu Trends That Define Dining Right Now,” by Priya Krishna (a brilliant writer who has generously shared resources for freelance food writers on her website!) and Tanya Sichynsky—and art directed/designed by Umi Syam.

I’m not particularly interested in food trend reporting right now—but there is something especially fresh and interesting about graphic-design-in-dining trend reporting! This is just visually so fun to read—and it dissects trends in food, drinks, menu typography, information architecture…

A design history of restaurant menu trends ✦

I have a special affection for restaurant menu design because one of my earliest amateur graphic design projects was designing a café menu in InDesign. Menus have clear informational demands: they need to coherently organize what’s available, including price and descriptions and other key information (like dietary restrictions). They also invite aesthetic exploration: menus can be ephemeral, expressive, visually adventurous.

I love menu design and I love design history—so Taschen’s Menu Design in Europe: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design, 1800–2000, is basically the ideal coffee table book.

The book has an essay by noted design historian Steven Heller (who is married to Louise Fili, an equally influential figure in American graphic design!) and features two centuries of incredible visual design.

Here, for example, is a spread featuring French menus during the Proust years, 1910–1919 (Proust’s In Search of Lost Time was published from 1913–1927):

There is something so delightful about the illustration on the left—the first capital M, with the stroke of each leg splayed out like a louche, exuberant figure…and the closing S, which bends backwards to almost embrace and contain the preceding letters…

Oh, and here’s a spread with a beautifully colored egg illustration for the French restaurant Jean-Luc Brendel in Riquewihr, Alsace:

And that’s all for this now. Thank you for reading! If you are writing, designing, drawing, painting, or otherwise making something this week, I hope your efforts will be rewarded. 💞

To say that I threw out those 9 other ideas isn’t quite right, though. They weren’t useless—producing them was necessary, vital even, to get to the 1 idea that really worked!

I found this quote in Geeta Dayal’s book, Brian Eno’s Another Green World. It originally comes from an interview Brian Eno did with Charles Amirkhanian on KPFA, a radio station based in Berkeley, California. You can listen to the video on YouTube or on the Internet Archive.

This quote appears in…the Wikipedia article for Long Day’s Journey Into Night. This is not an especially impressive citation, I know, but I’m busy researching my other writing project! Sorry to be so basic here!

I love the comment acknowledging that finishing is itself a skill. Up until now I’ve thought that “being bad at follow through” is my mortal flaw, but it’s great to recontexualize it as something I can work on, like writing itself. It is really fun that hitting “publish” on imperfect works teaches me more about how to write better than leaving a million unpublished, unfinished drafts in Google docs.

I absolutely loved this piece and really resonate with the low barriers to starting new things and the difficulty in finishing them. I’m so torn on the note-taking piece; I recently read that MLK Jr inadvertently plagiarized many of his speeches and even written work because of his style of note taking and it’s made me hyper aware of how to best take notes, attribute ideas, and have some cohesion to that strategy