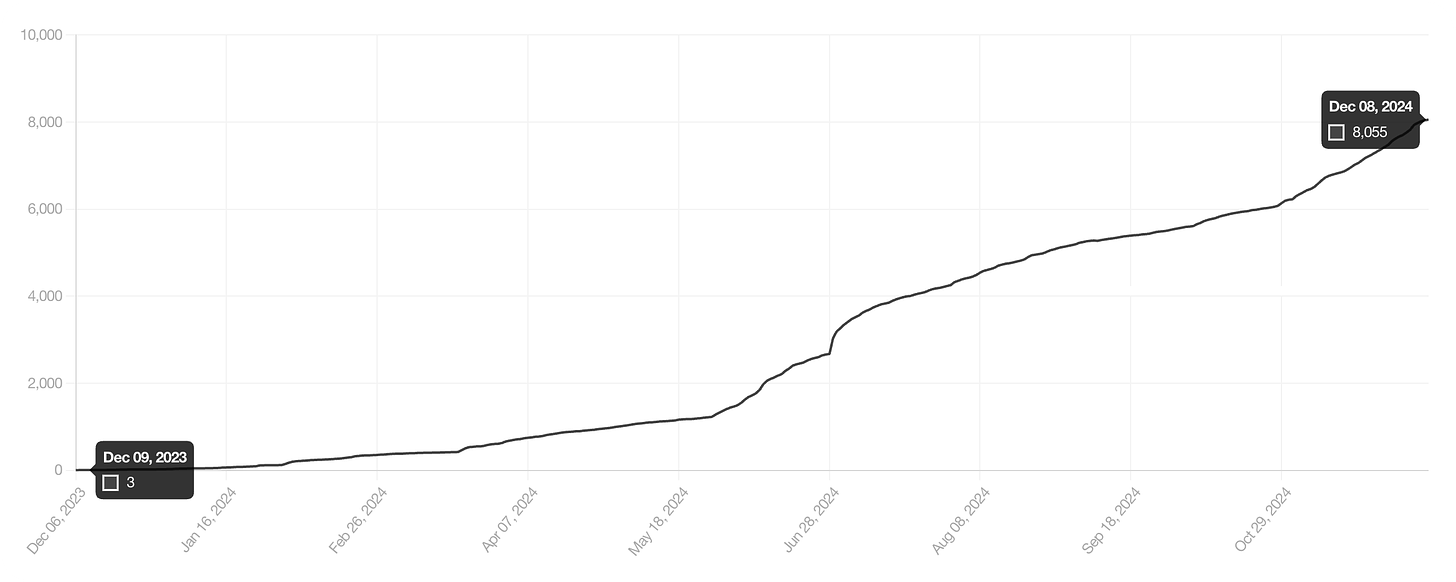

I started this newsletter one year ago, on December 9, 2023. The reason I started writing is ridiculous and a bit embarrassing: I’d been following two newsletter writers who lived in the Bay Area—

, who writes about fashion and style; and , who writes about food—and they announced that they were hosting a meetup for Bay Area-based Substack writers. At the time I was desperate to meet other writers, but I realized that it would be awkward to attend without a newsletter of my own. I wrote my first post without thinking too much about it; I remember doing final edits at the airport, on my way home from NYC, and pressing Publish as soon as I got back to my apartment, two hours before the meetup began.In retrospect, only something like this—an arbitrary deadline and an opportunity to socialize with other writers, which required I actually meet that deadline—could have convinced me to start writing. I was already subscribed to a few newsletters about a wide range of topics: literature, urbanism, tech, politics, fashion, food. I had also, in the late 2000s and early 2010s, read hundreds and hundreds of blogs. It was exciting and invigorating to come home from school every day, open up Google Reader, and see what all these people—sometimes professionals in their fields, but also amateurs and hobbyists—could teach me about the world.

I was a long-time reader of blogs and newsletters. But I had never written one: partly out of laziness, partly out of fear that I had nothing to say. Once I started my newsletter, however, it seemed obscurely important that I continue writing—3 more posts in December, 5 in January 2024, before I settled into a loose schedule of writing “weekly-ish” posts.

I began personal canon by accident—and only now, 34 posts and one year later, do I understand why I kept on going. This post is partly about writing a newsletter and building an audience for your writing, especially on Substack. But it’s also about what forms of writing are personally and societally meaningful, and why it’s felt so meaningful to spend the last 12 months writing about my love of literature. Below:

All the rules I broke, and all the advice I didn’t take (but maybe should have?)

Why write a newsletter, and how it can be valuable to you and others

Useful resources and (potentially) useless advice

Writing this newsletter has made life very interesting and exciting. An early Substack mutual—back when 120 people were reading my newsletter—emailed me and suggested we get coffee; he’s now a dear friend and introduced me to other friends that I would write with every few weeks. In the spring, another mutual reached out after a friend sent her one of my posts. We had that rare and wonderful kind of conversation—totally engrossing, intellectually activating—that tends to generate more writing, more ideas, more energy in my life.

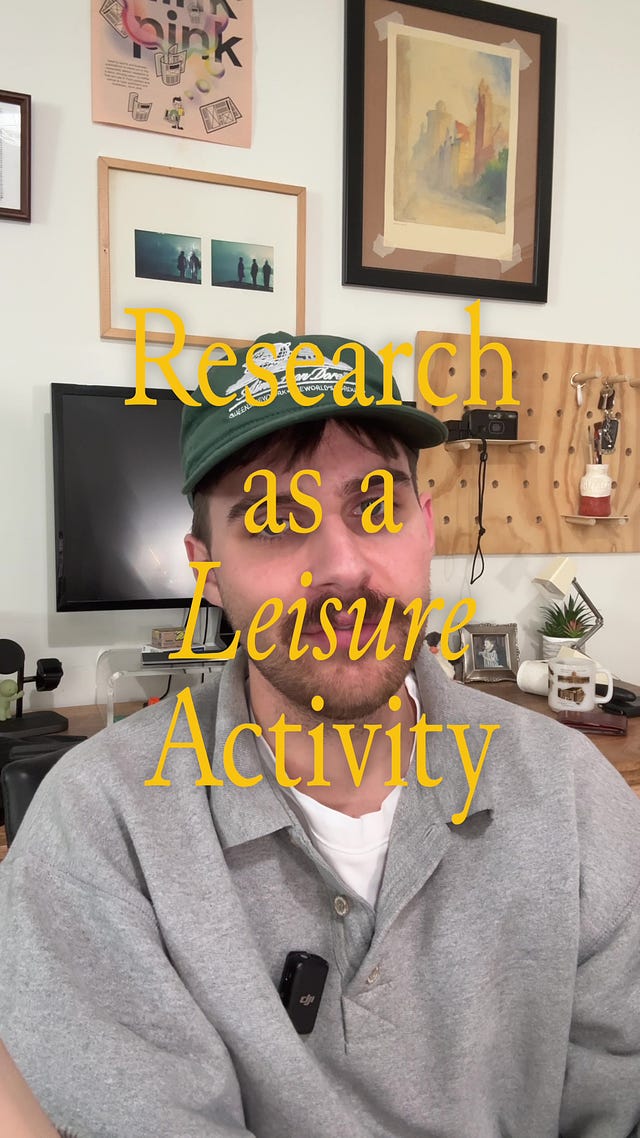

That post, research as leisure activity, went legitimately viral. It was featured on Substack Reads and shared on Hacker News. A friend I hadn’t caught up with for years told me that she found the link through an old-school, handmade website, clicked through, and realized that she recognized my name. Months later, I started getting DMs from friends who had seen a Tiktok by the artist/designer/researcher Matthew Prebeg, where he talked about his own research practice and how it informed a piece on digital decay.

A woman stopped me on the sidewalk, in San Francisco’s Mission District, and told me that she subscribed to my newsletter and had started reading the philosopher Agnes Callard’s Aspiration: The Agency of Belonging after reading about how Callard’s book changed my life. When my girlfriend and some friends hosted a coffee shop/closet sale/fundraiser, I posted on Substack notes, not really expecting anything to come out of it, and 4 people came by.

But the most exciting outcome was this: I became someone who could just come up with an idea for a post, start writing, and finish. For most of my life, I felt like someone who was always coming up with ideas for projects and then never executing on them. There were the usual excuses: school was busy, work was busy, I didn’t have the time. But I hated feeling like all my ambitions were evanescent and illusory; that my free time couldn’t be mobilized into some more directed, sustained project instead of scrolling on my phone for hours. Writing this newsletter has given me the faith that I can just do things, if I put time and energy into them.

So that’s how things have gone in the past year. Here’s how they began.

All the advice I didn’t take

Early on, I intentionally ignored a lot of well-meaning and useful advice about how to start a newsletter, how to start a successful newsletter, how to grow a newsletter—you get the point. I’m not against advice; it’s useful to learn from others!

But it seemed like there was something very delicate and fragile about the fact that, after years of reading other people’s writing, I had started writing myself—and I felt very strongly that I could kill that instinct, stifle it and ruin it, by taking the wrong advice.

So here’s what I didn’t do:

I didn’t tell anyone about my newsletter. I was afraid of two things. First: if I announced I was starting a newsletter and then struggled to keep it going, the embarrassment of falling behind would make me feel ashamed and inadequate, and eventually—after the obligatory Sorry I haven’t posted anything for a while! posts—I would stop writing. Second: I was afraid that having friends and acquaintances read my writing would paralyze me, and I would ruminate incessantly on things like Do my friends think I’m a bad writer? Are they secretly laughing me and calling me pretentious behind my back?1 So I didn’t tell anyone and I wrote in secret, largely, for the first few months of my newsletter. This meant that many of first readers were strangers, and their positive feedback meant a lot—they had no reason to ingratiate themselves with me or to care about my work. One of my closest friends only found out about my newsletter 4 months later, when I wrote for The Atlantic and she saw my newsletter linked in the bio. The literary scholar

has a similar approach with his Substack:I didn’t pick a niche. I have often admired and envied people who have their one thing—whether it’s literature, urban planning, art history, sociology, mathematics, architecture, software—because I have never been able to commit like that. The usual advice is to “niche down” if you want to build an audience for your newsletter, but trying to pick a niche terrified me. It activated all these existential questions about who I really wanted to be, what I cared about most…and trying to answer those questions, I felt, would get in the way of just writing. In my early posts, I avoided picking a niche or even trying to explain what my newsletter was about. I wrote about books, then psychotherapy, then eggs. This felt ridiculously inconsistent at the time, but I’ve come to see it as strategic; as the tech journalist

notes, some of the best newsletters offer “a particular attitude or perspective, a set of passions and interests, and even an ongoing process of ‘thinking through,’ to which subscribers are invited.”I didn’t have a set schedule. Content creators are always exhorted to set clear expectations—like uploading a YouTube video every Wednesday—and following through. I’ve never done this, because I wanted writing a newsletter to feel like an actual hobby, not something akin to work and therefore work-shaped, with deadlines and deliverables. Instead of writing a post every week, I send them out “weekly-ish”—which meant that sometimes I’d publish 2 posts in a week, and other times I’d be quiet for 3 weeks. I was afraid that the pressure to post every Wednesday at 9 AM, say, would lead me to inflict half-finished posts on people’s inboxes. I was also afraid that, if I missed my self-imposed deadline, I would disintegrate with embarrassment and shame—and eventually stop writing.

I wrote long posts. The usual advice is that people don’t read. And if they’re reading, they’re not reading posts that run much longer than 2,000 words. In theory, I agree—and I’ve often wondered if my posts would reach a bigger audience if they were shorter. Unfortunately, I’m dispositionally inclined to be very long-winded, and it takes a lot of editing for me to be brief.2 I’m regularly inflicting posts above 5,000 words on my readership, which is a lot to ask of people! But I’ve also found that some of those posts end up resonating the most with people. Both of the posts below are around 5,600 words:

I didn’t pay attention to my stats. If I really wanted to grow my newsletter, I would closely track subscriber growth (and especially subscriber growth before/after sending out a post), views, open rates…whatever other stats Substack provides…I really don’t look at any of these more than once a week. It matters a lot, obviously, if you depend on paid subscriptions as a primary or secondary source of income. But I didn’t start my newsletter with any aspirations to write full-time—I’ll cover my actual goals below, under Why write a newsletter?—and so compulsively checking my stats feels like an exercise in self-harm. I tend to think, impractically and idealistically, that what matters most is writing work that satisfies one’s own taste—and sharpening that taste through reading other writers and closely attending to what makes them feel so compelling and interesting and worth subscribing to.

All the above must be caveated with the things I did do:

I didn’t share my newsletter elsewhere, but I posted on Substack Notes a lot. Notes is Substack’s vaguely Twitter-like feature, and I’m pretty sure that resharing my posts there helped—but it also helped, probably, to restack other people’s writing on Substack; to post about poetry I liked:

…or research papers:

…or essays:

I didn’t pick a niche, but I made it clear what the overall ethic of my newsletter was. I think

’s advice is very useful here—people need to know what they’re getting out of your newsletter, which is different than confining yourself to a niche. The one-liner description I currently have for my newsletter is “finding meaning in life through literature, art, design, and culture,” and I expand on that theme on my about page:This is a newsletter about trying to live a meaningful, intellectually engaged, self-actualized life. It’s about how to take your intellectual, artistic, and literary aspirations seriously—especially when you’re no longer in school or academia but have an urgent, unstoppable desire to keep on learning, making, and growing.

This has turned out to be a nice, capacious container that lets me write about basically anything that I want: representation politics and contemporary painters; the philosopher L.A. Paul; how to write a book review; and influential modern architects.

I didn’t have a schedule, but I had some structure. Every month, I write an “everything i read” post that includes brief book reviews, and May onwards I included film reviews as well. And all my posts—except for those monthly roundups—include a list of five recent favorites at the bottom. (The actual number varies; sometimes I get lazy and just include 3.)

I wrote long posts, but I tried to make them as readable as possible. I lean heavily on headings, images and lists (like this one!) to make the text more scannable. In many posts, I include some summary at the top about what the post covers. The monthly reading roundups have bulleted lists of how many novels, nonfiction books, films &c are included. In more recent essay-ish posts, like don’t deceive yourself, I’ve also started mentioning the books and essays referenced at the top:

In this post — Joan Didion, “On Self-Respect” ✦ Elsa Morante, Lies and Sorcery ✦ Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary ✦ The Philosophy of Deception, edited by Clancy Martin ✦ Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina ✦ Oliver Burkeman, Meditation for Mortals ✦ Aschen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists ✦ Gabriel Winant, “Exit Right”

I didn’t pay attention to my stats, except for two: The number of comments I received, and the time I spent writing. Comments are much more informative than a mere view or like; they tell me what resonates with people, and why. The time I spent writing mattered because (as I’ll discuss more below) I came to see my newsletter as a place to practice writing. And one of the most important things to practice is simply putting in the time. One concept I find useful here is leading versus lagging indicators. Leading indicators predict future performance; lagging indicators reflect past performance. The time I spend writing is a leading indicator, since it roughly reflects how much writing I can publish and the quality of said writing. But the number of subscribers I have is a lagging indicator; those people have subscribed to me based on what I’ve already published. As James Clear notes in Atomic Habits:

You should be far more concerned with your current trajectory than with your current results…Your outcomes are a lagging measure of your habits.3

Why write a newsletter?

Even though I started my newsletter on a whim, I couldn’t have continued if I didn’t have some reason for writing it—for me, and for whatever audience I might receive. For me, there were 3 reasons to continue writing personal canon:

Writing helped me confronting my pathological fear of self-promotion, and forced me to practice putting putting my work out there

It also gave me a place to practice writing, and in the process find a community

And it let me advocate for the importance of literature and the humanities—from a very specific point of view

Confronting my pathological fear of self-promotion

A month before I started this newsletter, I’d published my first book review, of Mieko Kanai’s novel Mild Vertigo. It was something I’d worked hard on and felt proud of, but the thought of tweeting about it made me want to die. I only managed to do so because I texted to a friend, who tweeted about it for me, which made me realize, Oh god, I should really say something; and that made me realize that the tremendous feeling of despair I felt about sharing my work was a little strange.

I had this obscure fear of putting myself out there, and I began to feel that it was holding me back—from getting people to read my work, of course, but potentially also from even writing in the first place. I had somehow internalized this idea that to seek attention, to seek an audience was craven and base; if I did so, I was debasing the pure and noble intentions I had as a writer.

It’s funny to write this now, because I no longer believe it. While it’s obviously valuable to retain some skepticism about clout-chasing and attention-seeking, too much of it is genuinely destructive to anyone trying to sustain a creative practice. Writing my newsletter was a way to practice believing that—believing that it was not obnoxious and horrible to write publicly and promote it in small ways. And I do mean small. I was only able to post about it on Substack Notes because no one I knew was on there; now, unfortunately, there are lots of people on Substack Notes, including people who actually know me. Fortunately, I have also sorted out some of my strange psychological hang-ups about self-promotion.

Practicing in public

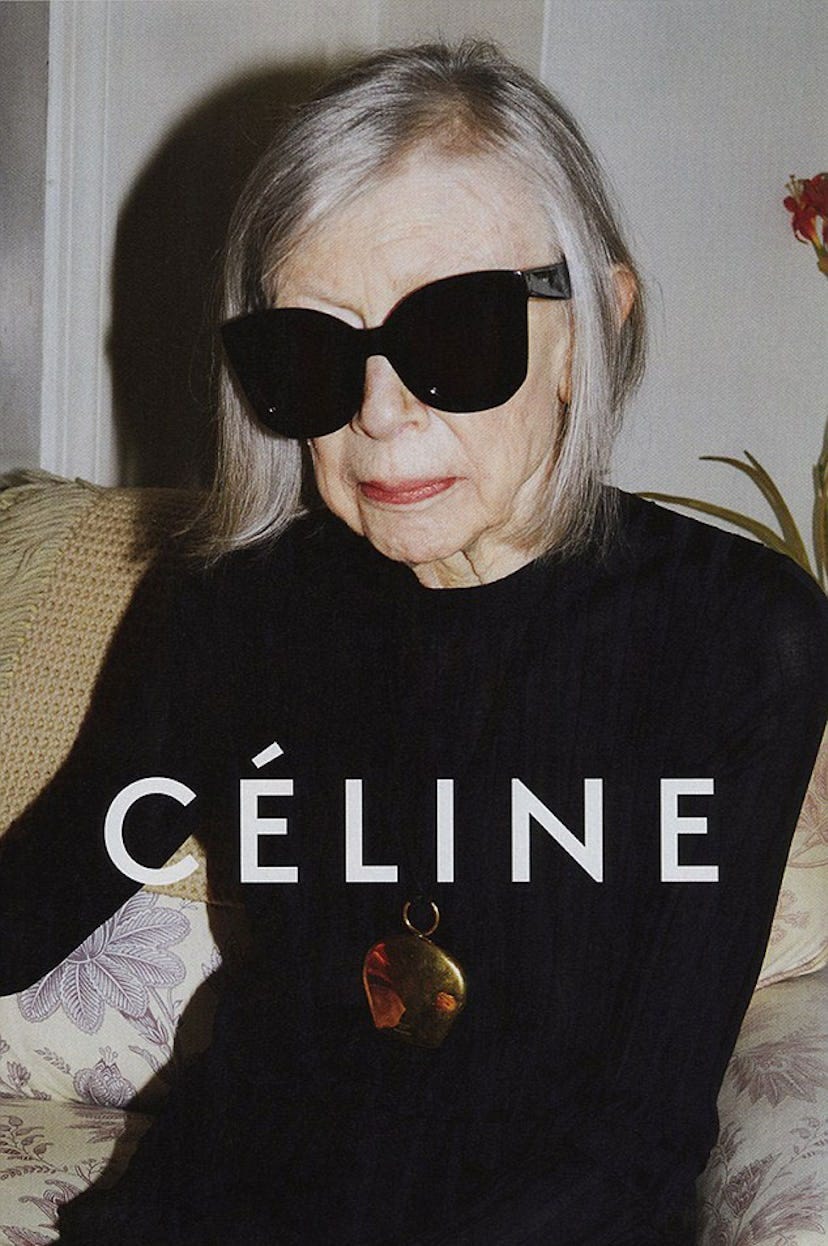

I’ve long been envious of those late 20th-century writers who had weekly columns or magazine jobs. Joan Didion, for example, arrived at her much-admired style through writing photo captions for Vogue in the ‘60s, back when “captions were surprisingly substantial pieces of writing, accorded what might seem a remarkable amount of editorial care,” as Brian Dillon observed.

And the inimitable Fran Lebowitz had a column in Interview Magazine:

I told [the editor] I wanted to write movie reviews…It was a way to be funny. It’s not that I was a film critic. I wasn’t! I said right away I wanted to write movie reviews of just bad movies and I want my own page, the back page, and I want no editing, and he agreed to everything.

What I envied wasn’t just the prestige or credibility that Didion and Lebowitz had—it was the chance to write, regularly, for an audience that expected something of you. They wanted to be entertained, engrossed, invested. They wanted intellectual vigor and literary style. It took me a while to realize that there’s a readily accessible 21st-century version of having a column: writing a newsletter or a blog.4

The novelist and journalist

used to have a blog; she now writes newsletter on Substack. Charlotte Shane had a blog and a newsletter, and as she said in a recent interview with :I built my reputation that way, and a lot of my readers were/are other writers, which has been wonderful and extremely advantageous.

The writer Kate Zambreno also had a blog, which is obliquely mentioned in her novel Drifts. I tried to find more information about it for this post, and was surprised by how moving—because it’s relatable, because it’s aspirational—this description of her blog is:

On the last day of December 2009 Kate Zambreno, then an unpublished writer, began a blog called Frances Farmer Is My Sister, arising from her obsession with literary modernism…Widely reposted, Zambreno’s blog became an outlet for her highly informed and passionate rants and melancholy portraits of the fates of the modernist “wives and mistresses”…Over the course of two years, Frances Farmer Is My Sister helped create a community of writers and devised a new feminist discourse of writing in the margins and developing an alternative canon.

And then there’s Roxane Gay, who wrote for HTMLGiant, a literature blog started by

, from 2009 to 2014. (I can only assume that she quit because her novel An Untamed State and essay collection Bad Feminist came out in 2014, which catapulted her to literary stardom.)These examples are encouraging. But even if I remain a minor writer, doing my little book reviews and my little informal essays, it’s still worth it to write a newsletter. It’s helped me practice very specific writing skills, for one thing. My second post was about how hard it is to write “mere descriptions” of things, especially books. While writing my first book review, my editor Philip Harris had observed that I was missing a basic synopsis of the novel—and writing that synopsis was quite difficult!

Since then, I’ve published a few more “real” book reviews. But this newsletter has also let me write more informal synopses as practice: 125 over the past year, across 12 posts (my monthly “everything i read” ones, plus my list of favorite books I read in 2023). From May onwards, I started including mini film reviews as well, and have written 18 of those this year. So I really have gotten a lot of deliberate practice in describing books and films!

Writing about literature during the “death of the humanities”

Even though I don’t have a niche, really, this newsletter is mostly about books. There’s an obvious explanation for this: I read a lot of books, so I have a lot to say about them. But the longer I kept up this newsletter, the more I started to feel—quite passionately, it turned out—that there were three animating beliefs behind why I wanted to write about them so much.

The first belief is that reading “seriously” matters, especially if you take your taste/intellect/capacity to create seriously. The definition of “serious” is highly personal, of course, but all of us have an instinctive sense of what it means and when we aren’t doing it. We usually know when we’re reading something that’s good for us—and we know, as

writes, when we’re consuming “junky” content instead:There’s no formula, or source from which you can easily and consistently tap for a wellspring of creativity, but there are certainly some general rules, such as the fairly basic claim that good inputs are a prerequisite for good outputs. The notion that an artist can live with indifference—absorbing junky content, having junky conversations, inhabiting junky environments—and still end up creating good art is, perhaps, rather fanciful. I won’t define the word junky for anybody else, although I’m pretty sure every reader will know, instinctively, immediately, how they would define the word for themselves, and how they would describe the environments that, for them, hinder creativity.5

The second belief is that there’s a dearth of writing online that discusses “serious” literature in an accessible, intimate register. I feel this keenly because I still see myself as an outsider in this world; I didn’t go to a liberal arts school, I didn’t major in English or comp lit, and (nearly) everything I’ve learned about literature has come from para-academic or entirely amateur contexts.

Within the world of people who have studied literature “for real,” there is sometimes this pleading, panicked discourse about how no one cares about literature, especially those gross and craven STEM types.6 But what I’ve found is that there are so many people like me—people who studied computer science and then felt some irrepressible longing towards literature and art and the humanities, who exert a great deal of effort to self-educate themselves in these domains. They want to read seriously, but they need a way in, and inviting and accessible discussions of great works mean a lot to them. (They certainly meant a lot to me.)

And even if people who don’t feel this particular kind of disciplinary anxiety—well, sometimes you want to discuss “serious” works in unserious and playful ways! There’s a style of writing that can be too careful, formal, excessively studied—and that style, I think, often obscures the genuine pleasure that you can get from reading.

The third and final belief is that people will care about literature if you make a compelling case for it. I can already hear the objections to my last argument—that, yes, there may be some intellectually curious people out there who are not “literature people” but want to be; but surely there are many more heathens who don’t care at all?7

This argument assumes that what people care about is already set in stone, and all you can do is react to their extant desires. But I don’t think this is how people work! What we care about and what we value is fundamentally social, inextricably influenced by the people around us. My interests, in many ways, have been shaped by the bloggers I followed as a young girl. I became interested in avant-garde Japanese designers like Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto because of fashion bloggers like Tavi Gevinson,

and Susie Lau. I started to see designing and writing as practices that came together because I admired people like Frank Chimero so much.A lot has been written about how the internet radicalizes people. But the same dynamics that turn a slightly lonely young man into a seething misogynist—recommendation algorithms; social contexts that concentrate and intensify discourse—are also the dynamics that turn a young person who “likes reading” into someone who spends a year reading Proust, and then the next two years trying to find friends who want to reread Proust together.

These dynamics are acting on us all the time. If you’re a writer, you can choose to intentionally enact them on whatever audience is available to you. The preexisting audience might be quite small, but if you’re a good writer, you can make the audience for your interests bigger. As the English poet William Wordsworth said, “Every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great and original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.” Or, as the critic

wrote in a recent newsletter post:It’s possible to get people interested in what interests you if that’s what you want to do. The number of people…will fluctuate by topic and by the means available to you. And the easiest way (in my experience) to convince people…is just to proceed with the confidence that those things are interesting and that other people will see what you see.

When it comes to getting people invested in literature, I tend to believe that the right approach is not to beat people over the head with lectures about how literature is really important; it cultivates moral and ethical qualities in a person; if they don’t read books, or they’re reading the wrong books, they’re dumb and cringe and uncool.

It’s more useful and rhetorically effective to simply model what it means to care about literature, and how engaging with it can shape one’s life. If you seem like someone interesting and even admirable, then the people who encounter you will see a preoccupation with literature as interesting and admirable as well.

Basically, I am suggesting we harness parasocial dynamics for good. If you really work on your charm, you can do things like sell 4 copies of a Romanian surrealist Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid off the strength of your devotion for the novel and the devotion your friends feel towards you. (It’s 640 pages and one of the greatest reading experiences I’ve ever had. If you buy a copy, let me know so I can feel even more pleased about my capacity to sell books to people.)

Advice and resources for newsletter writers

At this point, it seems appropriate to I offer advice to people who want to write newsletters. I’ll split this into 2 sections:

My advice (and when you should ignore my advice!)

Resources on newsletter writing that I’ve found most psychologically and practically helpful

My advice (and advice on when not to take advice)

My qualifications: 0 to 8,000 subscribers in a year, demonstrated ability to use a keyboard. (Note that this does not include Makes a living off of Substack; if you want that advice, please proceed to the section below.)

My high-level advice—which supersedes everything below—is that you should decide what you want from your writing, and then completely ignore any advice which detracts from this goal. This includes advice which is practically sound but psychologically destructive when it comes to sustaining motivation.

But if you don’t have strong opinions already in place, here are mine:

Headlines really matter. This is something that

, whose newsletter is an invaluable source of Substack advice, repeatedly emphasizes. The headline is what gets people to click or tap in—and learning to write a compelling headline, one that frames your writing in an authentic and exciting way, is a micro-skill that is worth cultivating!Spend twice as long on your intro paragraphs as the rest of the post. Earlier this year, I came across the following idea: Readers don’t have short attention spans—they have short enchantment spans. There’s an infinite amount of content out there, and readers know it. The introduction convinces a reader that their finite time alive is best spent reading this piece in front of them, and not all the other things on the internet. If you can convince a reader that your post will be meaningful to them, and they’re in capable hands, they will stay with you for a 5,000 word post—or even a 10,000 word one.

You can write about anything you want—but certain topics have certain audience sizes that are hard to exceed. I sometimes see people posting plaintively on Substack Notes and asking, If I write about —, would people be interested? The unhelpful answer is always Yes, but. Certain topics are just more interesting and/or easy to consume. If you write about about love and friendships, you’re touching on two of the most central and universal human concerns. If you write about gossip in the rare books–selling community, you need to be an exceptional writer and an existing audience that can make a niche piece go viral. Tired takes on why men are trash/women are shallow are constantly circulating online, alongside shallow takes on the Tiktok trend du jour. An essay about Hannah Arendt will rarely have the same reach, even though Arendt is inarguably more worthy of analysis than the average video about why “thought daughters” are problematic. The musician and tremendously successful YouTuber Andrew Huang touches on this in his podcast episode with Francis Zierer of Creator Spotlight. Huang one of the most popular creators on the internet—but for music production content, which is inherently a smaller niche than content about cars or computers.

However, you can expand your audience size through charismatic and compelling writing. As I said above (with the help of Wordsworth and

), if you care deeply about something, you can compel other people to care through your work. You may find, too, that it may seem as if no one cares as intensely and passionately as you—but once you start writing, all these people come out of the woodwork who are just as invested as you. Sometimes they’ll be other writers, and they’ll become your “writing community.” Sometimes they’ll be primarily readers, who are so gratified and excited that someone has finally articulated something that is so important and meaningful to them, and yet they rarely see talked about. has a very moving articulation of how writing can help you find your people. It’s beautiful, he writes, “to have a stranger arrive in your inbox, and they are excited by exactly the same things as you! You start dropping the most obscure references, and they’re like, yeah, read that, love it. The first handful of times it happened, [my partner] asked me what was wrong. I was crying in the kitchen.”Remind people to like and subscribe. I used to think it was ridiculous and pointless when YouTubers would do this. Then I began writing this newsletter. It turns out that people can appreciate your writing immensely, and yet still forget that subscribing is an option! If you’re anything like me one year ago, then asking people to subscribe—in the middle of a post that you have put hours and hours into—will feel like a deep betrayal of your principles, a clear sign that you have abandoned your humility and sensitivity and become a clout-chasing demon. But that’s really not the case. You’re just telling people that if they like your work, they can receive notifications when there’s more of it to read.

Advice from others (some of whom actually know how to make money)

The list below is loosely organized from more idealistic (focused on community and voice and quality) to more pragmatic (focused on growth and monetization):

- on writing online as a “very long and complicated search query” to find your people: “Having idiosyncratic interests that grow in complexity means that if you pursue them too far you will end up obsessed with things that no one else around you cares about…[but] you can get out of this mess if you want to. You do that by writing online (or publishing cool pieces of software, or videos, or whatever makes you tickle—as long as you work in public)…you are not the only person who has no one to talk to about the things you get obsessed by.”

- ’s advice after 3 years of writing a newsletter: “What most successful Substacks offer…[is] a particular attitude or perspective, a set of passions and interests, and even an ongoing process of ‘thinking through,’ to which subscribers are invited.”

- ’s 2-year reflection and the lies we’re told about internet success: “A lot of people believe that making a living in cyberspace means figuring out what kind of slop people are looking for [and] mass producing it…[this] is based on two pervasive lies. First: that it’s easier to operate in bad faith than good faith…more satisfying to dupe someone than to delight them…The second lie: success comes from contorting yourself to other people’s desires.”

- ’s excellent analysis of Matt Yglesias’s career, and what lessons it offers for bloggers and newsletter writers: “There are all kinds of things you can do to develop and retain an audience—break news, loudly talk about your own independence, make your Twitter avatar a photo of a cute girl—but the single most important thing you can do is post regularly and never stop.”

Alex Hazlett and Dan Oshinsky’s five types of indie newsletter business models: the Analyst, Curator, Expert, Reporter, Writer. Very useful even if you don’t plan to monetize, as the post goes into why people subscribe to each type and how they grow. This post comes from the Inbox Collective, a weekly newsletter about…running a newsletter.

- ’s precise and useful explanation of how Substack’s network effects work and how to use them: “My advice to those just starting out on this is to engage other writers in your niche…Your aim is to form a supportive cluster within the larger network, encouraging and championing one another. Within that cluster, it pays to be a high centrality node — the writer who knows and engages with all the other writers in your niche. In this sense, you really get out of it what you put in.”

Francis Zierer’s Creator Spotlight is a weekly podcast and newsletter that interviews successful writers and creators. I rarely listen to podcasts, but finished 4 episodes in 2 days—for reference, I usually listen to 4 podcast episodes a month—after discovering it.

The YouTuber Andrew Huang’s book Make Your Own Rules. Huang is a musician and composer who runs an extraordinarily successful YouTube channel. The book devotes equal attention to craft and commercialization. On the craft side—his advice on how to come up with ideas, and how to keep your creative practice fresh, is incredibly useful even if you’re not a musician! On the commercial side—his story about growing an audience from the early days of YouTube to present is very useful for anyone trying to understand and leverage an emerging platform, like Substack. (This isn’t me saying that Substack will be the next YouTube! But the company obviously wants to be something kind of like the next YouTube…)

And that’s all I have to say about writing a newsletter. (That’s all, I say, after inflicting over 6,000 words on you.)

Thank you, as always, for reading my newsletter and letting me practice in public. I feel very lucky (genuinely!) to have such a generous and interesting readership! I’ll see you in the next post, where we will return to discussing BOOKS.

This newsletter is free and will remain free for some time. But if you’ve ever read one of my posts and thought, Honestly, I would pay money for this!—please forward my emails to a friend, or share my posts online!

Historically, it’s always been these strange, arbitrary feelings of shame and embarrassment that have held me back from writing in public. These feelings are often irrational, but irrational feelings can be very powerful—and at some point I realized I had to respect them and work around them.

So when I began writing my newsletter, I wanted to protect myself from anything that could activate those feelings; it was better to write for an audience of 3 people and not feel afraid, than write for an audience of 30 people and feel terrified every time I published a new post.

I’ve edited myself down to some quite strict word limits: 1,000 words for my review of Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries for ArtReview; 650 words for my review of Lucy Ives’s An Image of My Name Enters America for The Believer, which both appeared in print.

Both of those took just as much time, if not more, than the 3k–10k word posts I write on Substack. Writing a succinct piece takes time! And I tend to publish my newsletter posts when they are mostly done—and not comprehensively and thoroughly edited to the best of my ability. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin: “I have already made this…too long, for which I must crave pardon, not having…[the] time to make it shorter.”

Atomic Habits is another S-tier self-help book—it elegantly and succinctly synthesizes most of the relevant research and insights on how motivation and habit formation work. It’s also the perfect length, whereas most self-help books are far too long, relative to how much they actually have to teach you.

The obvious downside is that, in a blog or newsletter, you don’t have a professional editor to work with. A recent discussion at the The Point features

and debating the merits of working with an editor. I’m very much on the side of wanting to work more with editors—nothing has excised more of my bad writing tics, and simultaneously made me deepen my arguments and sharpen my style! But I’m writing for free and offering up my writing for free…so here we are. You’ll have to make do with my self-edited posts!Bolding mine.

This is one of those things that actually gets me angry—and I am not a very angry person, generally—when people posit some inherent and unbridgeable divide between “STEM people” and “humanities people,” not recognizing that many people are both. Rachel Connolly has an excellent and very funny piece in Slate about how annoying it is when someone thinks that

People have “math brains” or “creative brains,” there are “boy chores” and “girl chores,” and in any relationship you will have “the person who reads the map” and “the one who is social.”

Those heathens are often assumed to be Gen Z youth—I personally think people are far too dismissive of the “kids these days,” as I wrote about here:

I loved reading this! The research as a leisure activity article genuinely influenced my life a lot, as I finally started to go through the massive list of things I was interested in researching for fun, not for assignments, and looked into them! I decided the best way for me to do that was to start a publication and write the things I found in the random topics I researched, and even though it’s brand new I have been having so much fun with it. Being more active with posting has also made me more active with reading, and I have discovered some really cool people with amazing ideas on here! Not telling people I know about my writing has definitely made posting less daunting, and since I feel like I get something out of what I write I’ve been more consistent which is new for me. Thanks a lot for sharing your thoughts!

This is so wonderful to read, Celine! Congratulations on such a BIG year!

Your newsletters has been deeply meaningful to me. I found you at a time when I was really struggling with the lack of intellectual rigor in my own life, I was feeling sad and definitely in a state of "lack"... I found "Personal Canon" shortly after I started writing about books (in April of this year, with Sarah Fay's gentle kick in the pants) and in your writing I found an answer to my question of how I could have a more intellectually satisfying life given that I am not finding what I am looking for in my day job. I started using my newsletter as a gym for my brain and it has been truly transformative. Your work has given me so much food for thought, ideas for further reading but also -- most importantly -- validation that my inner life is worth fighting for. Thank you, always!