how to change your life, part 1: l.a. paul's transformative experience

on philosophy as self-help ✦ and the epistemology of queer identity

It’s been quieter than usual here lately! But here’s my excuse: I’ve been working on 3 other pieces. One was for The Atlantic and came out last week: I recommended "Six Books That Will Jolt Your Senses Awake” with vivid, evocative language. The article includes some of of my all-time favorite novels and memoirs, so if you’re an Atlantic subscriber, please do read it—and let me know if you pick up any of the books!

And if you found this newsletter through The Atlantic, welcome and thank you for subscribing! To briefly introduce myself: I’m a designer and writer with a deep affection for literary fiction (especially in translation) and beautiful graphic, industrial, and web design. I publish posts every week(ish), on topics like how to use Brian Eno’s oblique strategies to start and finish creative projects, how to write “mere” descriptions, and a cheerfully polemical defense of San Francisco.

Today’s post is about a topic very near and dear to my heart: How books can help us understand what we really want from our lives—and how they can inspire us to change. The most obvious way to understand your true desires, and embark on the difficult and rewarding journey of fulfilling them, might be to read a self-help book. But philosophy, I’d argue, is an even better way to do so.

In the last few years, there have been two major changes in my life. The first was deciding that I wanted to become a writer. I didn’t want to write full-time, but I wanted to be someone who took my writing seriously and regularly finished and published work. Three years ago, I was reading Julia Cameron’s iconic artistic self-help book The Artist’s Way and struggling to write more than once a month. This year, I’ve developed a habit of writing 5–10 hours a week, and it’s led to bylines in places like ArtReview and The Atlantic. I’m still not the kind of writer I want to be, in ambition and style, but I’m getting closer every month.

But the other major change wasn’t a choice, but a discovery: I realized that I wasn’t straight. At the beginning of 2019, I thought I knew who I was and what I wanted: I was a straight woman who wanted a reasonably egalitarian but mostly conventional heterosexual relationship. But that year I realized that there were were aspects of myself that were totally opaque and unknown to me. I realized that who I was, and how I understood myself, could change at any moment. That realization eventually led to me asking out a friend of mine (now my girlfriend of 4 years) and coming out to my friends, family, and coworkers.

Both of these were major changes to my sense of identity and my life. To understand them, I’ve turned to the work of 2 philosophers, L.A. Paul and Agnes Callard. Philosophy books can seem dry, abstruse, and irrelevant outside of academia, but I’d argue that they’re are incredibly relevant to the most important questions of our lives. How do we understand what we want and value? How do we change who we are? And how do we create a meaningful and fulfilled life?

I really think there’s no higher purpose to philosophy than to answer these questions. And you don’t need to be a philosopher—I didn’t even take philosophy classes in undergrad!—to make use of philosophical ideas. As the critic and lapsed philosophy PhD student

wrote last year:[I]f I’m not turning to philosophy to decide what to do with my life and what I owe others, if i don’t think it actually has anything to teach me about love and pain, why would I do it?

If we read philosophy as self-help, what can we learn about ourselves and our own agency? That’s the question I’d like to explore in my next 2 posts about how to change your life.

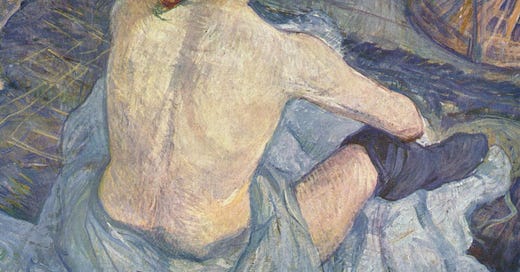

In part 1—this post!—I’ll discuss L.A. Paul’s Transformative Experience (2014), which describes how experiences as diverse as eating a new fruit, or becoming a parent for the first time, are personally and epistemically transformative experiences. I’ll then use Paul’s ideas to think about queer identity, and whether it’s OK to gatekeep queerness to people who are having, you know, actual queer sex.

In part 2, I’ll discuss Agnes Callard’s Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming (2018), which describes how someone becomes someone new, whether that’s becoming a more informed fan of a particular genre, or becoming a parent. Philosophers are like everyone else, it seems: the decision to have kids, or not, looms large over both Paul and Callard’s books. I’ll then use Callard’s ideas to think about becoming a writer, musician, or other “creative”, and how her theory of aspiration teaches us how to make those dreams real. I’ll also discuss the differences between Paul and Callard’s approaches.

Read part 2 here—

L.A. Paul’s Transformative Experience

L.A. Paul is a philosophy and cognitive science professor at Yale. Her 2014 book Transformative Experience is about how we make decisions in our lives—in particular, decisions that have dramatic consequences that are impossible to fully predict.

Paul opens the book with a thought experiment: You’re deciding whether or not to become a vampire. The decision is irreversible and will completely change your lifestyle and tastes. This is a fictional example, but it helps us understand other drastic and irreversible changes, like becoming a mother. How can you make a thoughtful, rational decision when you have no clue what the experience of being a vampire, or being a mother, is really like? You could obviously talk to other friends, or read about people’s decisions online, but none of those people are exactly like you, so you can’t be certain that their experience will help you in making your own decision.

There are smaller decisions where the outcomes are equally impossible to predict. Paul gives the example of eating a durian for the first time. Growing up, I remember my mom (a durian fan) buying durian-flavored ice cream and eating it while standing in a parking lot, while my father (a durianphobe) cowered in fear inside the car. Durians have an incredibly polarizing flavor, which makes it hard to predict whether you’ll love them or hate them. You can’t know, really, until you try it out.

As Paul writes,

Having a transformative experience teaches you something new, something that you could not have known before having the experience, while also changing you as a person. Such experiences are very important from a personal perspective, for transformative experiences can play a significant role in your life, involving options that, speaking metaphorically, function as crossroads in your path towards self-realization.

Before a transformative experience, Paul argues, you exist in a state of “epistemic ignorance”. You haven’t had the experience yet, so you don’t know something crucial. In the case of the durian, what you don’t know is very narrow: Whether you’ll like this specific fruit or not.

But what about a more significant category of transformative experience…sex? Sex—good sex, bad sex, consensual sex, coerced sex—can drastically alter how you see yourself, and others, and how you relate to others. It can change you in positive ways (by giving you an increased sense of confidence in your attractiveness or desirability) and in negative ways (by traumatizing you and impacting what you feel comfortable or uncomfortable doing in the future).

I’d argue that having queer sex for the first time—or even something more demure, like going on a queer date, or having your first queer kiss—is also epistemically transformative. Which sounds like a very bloodless description of something that is tremendously urgent and personally important in our lives. How do you understand your own desires, sexually or romantically or otherwise? How do you choose certain acts, like going to a gay bar or setting your orientation to Bisexual on Hinge, for the first time? When do you know that you’re 100% not straight? How are you supposed to find out?

On knowing your desires (and the infamous “Am I a lesbian?” master doc)

Let me be more specific. One problem with figuring out whether you’re straight or not, if you’re a woman, is that certain forms of homoerotic behaviour are encouraged by society, even when actual homosexuality is considered unnatural and strange. It’s normal to talk about your platonic friends as “girlfriends,” or confess to a “girl crush” on a beautiful woman, or kiss a girl at a party for “fun.”

One of the most influential pieces of internet pop culture ever created is the “Am I a lesbian?” master doc that circulated on tumblr and other social media sites for years and years before I came across it, in 2019, when I began questioning my sexuality. It describes how “compulsory heterosexuality,” a term originally used by the lesbian poet and feminist Adrienne Rich, can forcibly compel—or benevolently mislead—women into denying and suppressing their attraction to other women. Compulsory heterosexuality often leads women to misinterpret their desires and actions, assuming that they’re not serious feelings, or perhaps further evidence of heterosexuality. (Did you kiss a girl at a party and enjoy it? Well, maybe you enjoyed it because you were kissing for the male gaze!)

The master doc is also a document about epistemology. Caroline Godard, writing for Post45, notes that the doc sees compulsory heterosexuality “a way of thinking about one's relationship to the world…an epistemological orientation that one can, with practice, choose to opt out of.” Opting out means reevaluating your past and searching for signs that you were really a lesbian all along.

I’m conflicted about the “Am I a lesbian?” master doc, to be honest. First off, it didn’t totally work for me because I’m not a lesbian, lol—I’m just a garden-variety bisexual. But it also emphasizes this unchanging, essential form of sexual orientation: You were always attracted to women, you just didn’t realize it. But somehow that didn’t quite capture my experience. To me, it felt like I had been straight for most of my life, and then one night I took an empathogen at a party, and I realized that the friend I was with was extremely hot. Only after that experience—a transformative experience—could I seriously entertain the idea that I wasn’t straight after all. It did feel, in a way, that queerness had appeared overnight in my psyche.

Without that experience, how could I have known that I wasn’t straight? Either I’d repressed my homosexual desires for my entire life, or I genuinely didn’t have any that felt serious enough until that point. Which raises the question: “are we,” Godard asks, “responsible for knowing our desires, and what impedes our ability to do so?”

Knowing our desires, Godard suggests, might involve not just understanding the past, but changing what we do in the future (bolding mine):

There is another view of desire, which is that it is inherently unknowable. Of course, desire always implies absence: we want what we don't have. But my point is that we often don't even know our desires; or we know some of what we desire, but certainly not all of it…desire and self-knowledge will always elude us, and I'm ultimately happy to exist in a world in which I can be curious and surprised about my desires, and, in turn, be curious and surprised by myself. To borrow Katherine Angel's words: "The fantasy of total autonomy, and of total self-knowledge, is not only a fantasy; it's a nightmare."

Desire is anticipatory — it is oriented towards what we want out of the future.

After that night, I didn’t think: OK, I’m definitely attracted to women! Instead, it felt like: Well, maybe. To borrow from Godard, I was “curious and surprised about my desires,” but they were inconclusive desires.

What I wanted was to have other experiences, more experiences, to help me understand my desires. I wanted to have the experiences that Paul’s Transformative Experience describes as “revelatory”—they reveal something about yourself. Crucially, you can choose to have a revelatory experience despite not knowing whether you’d find them “pleasurable or enjoyable.” It’s the epistemic ignorance problem again: Before the experience, you don’t know if you’d like it. You just have to try!

As Paul writes,

[W]e might choose to have an experience because of its revelatory character, rather than choosing it because…it is in some way pleasurable or enjoyable…[and] we may also choose to avoid experiences for the same reason.

Paul does something quite interesting here: She suggests that someone can choose to not be transformed by experience. Here are the notes I took while reading this:

is experiencing a queer relationship an epistemologically novel experience, compared to a heterosexual relationship?

maybe something here about “heteroromantic” people avoiding the revelatory experience of a gay/lesbian relationship?

At this point, we now have the theoretical framework to set up some hot takes about queer identity. Here we go:

“You’re still valid—” No! Bring back epistemological gatekeeping of queerness!

What does it mean, exactly, to call yourself queer? In the newest issue of The Drift, the writer

asks what queer identity means in a “lonely country…We’re having less sex than ever…and we’re getting sadder, too.” On one hand, queerness seems more normalized, understood, and celebrated than ever before. And yet:The world may appear gayer than ever, but it’s also less physical than ever. Queerness flourishes…through Twitter bios with parodically long strings of acronyms, and on Discord servers where young people create new gender and sexual identities on a semi-weekly basis…

Queerness is, or could be, a practice based in connection, one diametrically opposed to the loneliness of American life. Online, queerness is often no more than a word, one that does little to change our ever-more-isolating circumstances.

Online, being “queer” can simply be about claiming the identity. Now, there’s obviously a great deal of power in calling yourself queer. It can legitimate a desire that you have suppressed your entire life and felt ashamed of; it can inaugurate a new way of living, where you are open to what you truly want instead of what you have been encouraged—or pressured—to want. But is calling yourself queer enough? Moskowitz argues that it isn’t.

This argument also appears in

’s essay, “Lesbians Who Only Date Men,” where Dee observes that:as acceptance of minority sexual orientations and gender identity have grown, these categories have become much more nebulous. Rather than being guided by physical experience, one’s sexuality and gender identity are now determined by something much harder to define: feelings. The YouTuber Contrapoints may have put it best in a now-deleted tweet: “Gen Z people are hard to figure out. They’re like, ‘I’m an asexual slut that loves sex! You don’t have to be trans to be trans. Casual reminder that your heterosexuality doesn’t make your gayness any less valid!”

This phenomenon, Dee suggests, is part of a larger shift where identities that “once represented a lived experience…or behavioral pattern” are now just about vibes. Homosexuality is no longer about, you know, sex—you can simply “have an affinity for and a talent for projecting the homosexual affect."

Pointing out that queerness may require actual queer interactions with others does not make you very popular. It’s seen as gatekeeping, and gatekeeping is unfair. It’s not fair to gatekeep someone who just realized they were queer 1 week ago and hasn’t had time to go on a date yet! It’s not fair to gatekeep someone who lives in a rural, homophobic area and can’t find an IRL queer community! It’s not fair to gatekeep someone who is disabled and struggles to find the time and energy to date! And so on.

But the question of whether someone is “valid” or not is basically a distraction. And this question of gatekeeping—which assumes that it’s all about litigating who is and isn’t queer, assumes a simplistic and binary view of the world. (And why use binary thinking within a community that’s all about questioning, subverting, and escaping binaries?)

Instead obsessing over a hypothetical gatekeeper in the Queer/Not Queer binary world, let’s think about queerness as a spectrum of epistemological experience.

It’s obvious that a woman who just has a same-sex crush has a different epistemic experience of her sexuality than someone who’s actually kissed her crush, right? The question isn’t about whether the first woman is “queer enough,” but about what kinds of revelatory queer experiences she’s had. And that woman probably wants to actually kiss her crush and find out what it’s like, instead of merely thinking about it.

So yes, you can identify as queer without ever having had queer sex, in the same way that someone can be a virgin but still straight. But it should be uncontroversial to say that never having queer sex means remaining in a state of epistemic ignorance about your sexuality.

And it’s not just about sex, either. Over the past 4 years, I’ve had several epistemically transformative experiences of bisexuality:

I met a longtime friend for coffee and for the first time said My girlfriend and I… instead of My boyfriend and I… and observed his surprise

I came out to my parents and started to notice how cold, uncomfortable, and stilted they were whenever I brought up my girlfriend

Once—just once—I referred to my girlfriend as my “partner,” only to have the person I was speaking to go “Oh, what’s his name?”

A childhood friend of mine is getting married this summer. When we caught up over dinner, I mentioned to her—very briefly—that I was stressed about bringing my girlfriend to the wedding, where she would meet literally all of the other Việt people I grew up with. “It’ll be fine,” she said. “I don’t think anyone will be weird about it.”

But here’s the thing. She doesn’t know. Neither do I. We are once again in a state of epistemic ignorance, because I’ve never introduced these specific people to a girlfriend at a family wedding. Coming out as queer—and, more than that, showing up to an event with your actual queer partner— alters your epistemic relationship to the world.

When I first realized I was bisexual, I read so many posts online where people asked, “Am I missing out if I’ve never dated another woman?” And the response was always: No, girl, you're still valid even if you only date men! Even if you’re married to a man! You don’t need to have dated women to be valid!

But the concept of validity is a trap! It’s not interesting and it’s not helpful and if I could ask the discourse deities for one thing this year, it would be to permanently retire the idea of validating each other’s sexualities in such a tiresomely cheerful way.

Because the truth is that you are missing out if you never have a queer relationship. There is something you will never know about yourself. And while there is no ethical obligation to know, there is, often, a desire to know that should be honored. Most queer people instinctively understand that an actual queer relationship would change them. And many people long for that change.

And there are, equally, people who are afraid of that change. I’m thinking here of the girls I know who are desperately interested in other women and also terminally afraid of asking them out. On a pragmatic level, I’m really trying to understand how they expect to meet and date the woman of their dreams if they never make a move. On a philosophical level, I’m wondering if they’re afraid of revealing something uncomfortable. Like revealing that their ostensibly liberal parents are totally OK with gay people if the gays are somewhere else, not in your family. Or revealing that, deep down, they actually really don’t want to give up the familiar, reliable structure of a heterosexual relationship.

As Paul writes:

When we choose to have a transformative experience, we choose to discover its intrinsic experiential nature, whether that discovery involves joy, fear, peacefulness, happiness, fulfillment, sadness, anxiety, suffering, or pleasure, or some complex mixture thereof. If we choose to have the transformative experience, we also choose to create and discover new preferences, that is, to experience the way our preferences will evolve, and often, in the process, to create and discover a new self. On the other hand, if we reject revelation, we choose the status quo, affirming our current life and lived experience.

The world is more open than ever to queerness, but there are still complications. You have to think a bit more about whether to hold your partner’s hand in public. You begin to realize how many of your expectations for a romantic relationship were predicated on heteronormative assumptions: The man does this, the woman does this, people are sometimes unhappy about it, but there are conventions. You become extremely aware of the countries where homosexuality is still criminalized.

But I’m still profoundly, profoundly grateful I experienced all these things. As far as epistemological transformations go, being openly queer has been very positive so far. And all of this is in service of LOVE—the greatest transformation of all.

Four recent favorites

Amina Cain on interiority over conflict in literature ✦✧ Artist-designed perfume bottles ✦✧ Greg Jackson on poetry versus coke ✦ Are great cooks always men?

Amina Cain on celebrating interiority over conflict ✦

As a conflict-averse, interiority-obsessed reader and writer, I loved this passage from Amina Cain’s A Horse at Night: On Writing…via the writer and scholar Kola Heyward-Rotimi’s Twitter:

When we read novels or short stories we’re supposed to want tension and conflict, at least that’s what we’re often told, but I don’t care about conflict in fiction any more than the other elements that might appear there. It’s often narrative voice to which I’m drawn, for the way it sounds, for its interiority, and the way the reader can follow it through a narrative, for the way it can excite or unsettle and soothe.

Did you know James Turrell designed perfume bottles? ✦

In 2022, the artist James Turrell (known for installation artworks that play with light, space, darkness, and dimension) designed these perfume bottles for the luxury glassmaker Lalique…which I learned about through the designer Neesh Chaudhary’s Twitter.

Greg Jackson on poetry versus coke ✦

I’m slowly reading Greg Jackson’s Prodigals, a short story collection about the ostentatiously elite and dissolute. It’s tremendously quotable (almost too quotable—some of the sentences feel overwrought and overwritten, so that they’re as elaborately insightful as possible). Here’s a funny little scene from the opening story, “Wagner in the Desert,” where four friends—“filmmakers and writers…designers or design consultants…that strange species of human being who has invented an app”— go on an extended bender in Palm Springs:

I wanted to read a poem that had recently moved me. I had been trying to read it every night, as a prelude to dinner or a coda to dinner, but things kept getting in the way. The mood, for instance. It wasn’t a very poem-y poem, but it was a poem, and I guess it had that against it. Still, it was funny and affecting, and I saw it as a moral Trojan horse, a coy and subtle rebuke to everything that was going on, which would, in the manner of all great art, make its case through no more than the appeal and persuasiveness of its sensibility. The others would hear it and sit there dumbfounded, I imagined, amazed at the shallowness of their lives, their capacity nonetheless to apprehend the sublime, and the fact that I had chosen a life in which I regularly made contact with this mood. Don’t get me wrong. I didn’t expect this state to last more than a minute. But the poem had become meaningful to me as I felt increasingly stifled, or stymied, or something, and I was about to read it when dinner was very suddenly ready, and then when dinner was over dessert appeared, and then there were post-dinner cigarettes, and then we got a call that our cabs were on the way and we had to hurry to clear the table so that we could all do a few lines before the party. We crushed the coke into still finer powder and spread it, thin and beautiful, on the glass coffee table. And by the time we were packed into two cabs any memory that I had been about to read a poem, or that poetry was a thing that existed, had vanished.

Are great cooks always men? ✦

One micro-skill I’m practicing right now is writing really good headlines. A good headline frames a piece, efficiently and powerfully setting out the argument you’ll find inside it. I came across an incredible example of this recently: James Hansen’s essay “He Cooks, She Cooks. He Elevates, She Relates” for Taste, where Hansen observes how “greatness is bestowed” in fine dining—mostly on men.

Men are free to treat food as something to be gazed at and regarded—in the sense of both sight and regard, admiration, even lust—while women are encouraged to envisage food’s place in community, staying within the boundaries of their own identity.

I found this via

’s latest Substack post—Kennedy is one of my favorite food writers working today.Thank you, once again, for reading this. If you enjoyed this, feel free to reply to this email, comment, or DM me on Substack! I’ve had some nice conversations lately about pitching articles to publications, getting over the fear of hitting Publish, and psychoanalysis books…and I hope to have many more nice conversations with people this year!

another banger! I'm straight (for the most part, or maybe for now? who knows!) but have relationship & sex ocd and I'm literally always thinking about these ideas (for better or for worse 🙃). really appreciated what you said about the complicated notion of sexuality being "unchanging" as this is something that often PLAGUES me to no end and I loved that bit on the inherent impossibility of knowing one's true self and true desires. I guess there is a certain beauty in that ignorance and it doesn't have to be this moralistic journey. thanks for this! your writing is always a breath of fresh air. <3

I love philosophy so much so I adored this whole piece - exceptionally well done Celine! Very astute thoughts about sexuality and desire. I have been thinking a lot recently about epistemological transformations (I got diagnosed with a chronic illness a few years ago and it has radically transformed my life in a way I couldn’t access if I didn’t get sick!) it’s really interesting. Ps those perfume bottles are to die for. X