how to begin

on copying, technique and taste ✦ plus 6 close readings of great essay intros

When I was 22, I met a designer whose work I had admired and respected for many years. Halfway through our conversation, I worked up the courage to ask for advice: ‘I’m not capable of the work I want to do. How can I make better work?’

‘Take something you like,” she said, ‘and try to copy it exactly. Copying teaches you a lot about technique.’1

It was obvious that she wasn’t advocating for theft, for passing off someone else’s work as my own. Instead, copying was a tactic—something that would help me understand the decisions that went into a work.

I took her advice a few weeks later, and tried to copy a book cover I loved in Illustrator. Certain decisions were obvious and easy to grasp: colors, typefaces, use of imagery. But I began to notice all the minor decisions, the subtle accommodations between different visual elements, that had to be made as well.

When I first placed the title of the book on my canvas, for example, it felt crudely positioned, amateurish. Using my laptop’s trackpad, I dragged the text left, then up. I watched the text move, and I saw how the composition shifted along with it—the whole arrangement began to feel more purposeful, more crisp. When the text was finally in place, the whole thing suddenly and instantaneously locked in. It felt like a minor revelation. (I wanted a sound effect, at least, to acknowledge the moment.) The elements on the canvas were no longer disparate, lonely things. They felt coherent, and that coherence felt natural and inevitable. But it wasn’t. I had seen what it looked like before; I had seen the coherence happen in front of me.

Copying teaches technique and taste. It works for design and writing and many other disciplines. But with writing, I find that faithfully copying a work isn’t as instructive. What seems to be more useful is an approach I’ve been thinking of as ‘deep copying.’

The goal of deep copying is to:

Understand the specific moves a writer is making, in as much detail as possible. This involves a lot of close reading and reverse outlining. I’m essentially taking apart an essay and making extremely pedantic, precise observations: 12 paragraphs; first paragraph is 6 sentences long and opens with a quote, then context for the quote, then 2 short sentences, 1 long, 1 short. Why do details like this matter? Well, because the effect on me might be: The longer sentence was carefully argued, but hard to read; the shorter sentences right after energized me and made me want to continue.

Replicate the techniques and structure in my own work. This is where the ‘deep’ part of ‘deep copying’ comes from; I don’t want to make a shallow copy, where I write on the same topic with the same approach, argument, style. (This would be plagiarism!) But I might notice something like: The writer ends this section of the essay by posing a rhetorical question, then opens the next section with a quote that answers (part of) the question. That’s useful; that’s a technique I can notice and appropriate and deploy in an entirely different work.

The novelist Sanjena Sathian recently wrote about an exercise she gives to her fiction students, which helped me understand why deep copying is so useful:

Reading-as-process-not-project is something I try to impart to my students. When I first started teaching, I began my classes with several seminar weeks, during which we’d read published fiction for craft. Then, we’d turn to workshops, at which point students seemed to forget the pieces we’d studied so closely in the first month. Discussions often petered out as students realized a story needed something, only they couldn’t figure out how the writer could achieve that something. I got frustrated, thinking: The secrets you seek lie within you/your notes!

So, last year, I decided to throw more work at my students…I added something I call “craft journals.” Each week, in addition to reading their peers’ work, my students choose from a bank of 100+ stories, each of which offers specific craft lessons…They then write about their chosen story in a “craft journal.” They reverse-outline each piece to track its structure and try to articulate what they liked and disliked about it.

Today’s newsletter, then, is my public version of a craft journal. These days, I’m thinking a lot about how to begin—as in, very literally, what makes for a good beginning to an essay?

Below, I’ve chosen 6 essays that I return to often, because their opening paragraphs are so compelling. I’ll include my own analysis of why they’re good and and what minute decisions are being made.

In this post — Janet Malcolm’s ‘Advanced Placement’ ✦ A.O. Scott’s ‘How Susan Sontag Taught Me to Think’ ✦ Charlotte Shane’s ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ ✦ Alyssa Battistoni’s ‘Spadework’ ✦ Lucy Grealy’s ‘Mirrorings’ ✦ Andrew Solomon’s ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’

Three ways to begin, in cultural criticism

The essays below (by Janet Malcolm, A.O. Scott, and Charlotte Shane) all have one thing in common: they entice the reader first, and then introduce their subject. For Malcolm, the subject is a book series that would ordinarily be dismissed; for Scott, it’s a well-known writer that he takes a new angle on; and for Shane, the subject is more abstract: power and corruption in American politics.

Open with a striking contrast (Janet Malcolm)

There’s something deliciously exciting about Janet Malcolm’s 2008 essay ‘Advanced Placement,’ on a series of books about the high-stakes social lives of rich kids (and the middle-class hangers-on) in NYC. I am referring, of course, to Gossip Girl.

It’s a bold move to write about young adult fiction in the New Yorker, and what’s interesting to me is how Malcolm explains why these books—which seem insubstantial and childish—actually merit critical attention:

As Lolita and Humbert drive past a horrible accident, which has left a shoe lying in the ditch beside a blood-spattered car, the nymphet remarks, “That was the exact type of moccasin I was trying to describe to that jerk in the store.” This is the exact type of black comedy that Cecily von Ziegesar, the author of the best-selling “Gossip Girl” novels for teen-age girls, excels in. Von Ziegesar writes in the language of contemporary youth—things are cool or hot or they so totally suck. But the language is a decoy. The heartlessness of youth is von Ziegesar’s double-edged theme, the object of her mockery—and sympathy. She understands that children are a pleasure-seeking species, and that adolescence is a delicious last gasp (the light is most golden just before the shadows fall) of rightful selfishness and cluelessness. She also knows—as the authors of the best children’s books have known—that children like to read what they don’t entirely understand. Von Ziegesar pulls off the tour de force of wickedly satirizing the young while amusing them. Her designated reader is an adolescent girl, but the reader she seems to have firmly in mind as she writes is a literate, even literary, adult.

There is something archly intimate in the opening sentence, which references the famous characters of Nabokov’s Lolita by name only. (She doesn’t for example, contextualize the scene with: ‘In Vladimir Nabokov’s seminal 1955 novel, Lolita…’) It feels as if Malcolm is referring to her acquaintances (and it does often feel as if the protagonists of famous novels are everyone’s acquaintances, even friends); it also suggests that the reader of this essay comes from a certain literary milieu, where Nabokov is a familiar reference point.

But she picks out an unusual part of Lolita: the childishly vapid quotation That was the exact type of moccasin I was trying to describe to that jerk in the store. This quote is perfect for the move Malcolm executes next—a jump from a recognizably literary work to the seemingly banal Gossip Girl. The contrast is exciting! It’s unexpected; it creates surprise and therefore energy.

In the next few sentences, Malcolm insists that von Ziegesar’s books are worthy of her attention, and that her consideration of them is worthy of our attention. She does so first by acknowledging any suspicions (Von Ziegesar writes in the language of contemporary youth—things are cool or hot or they so totally suck) and then explicitly addressing them (But the language is a decoy).

Malcolm then establishes her argument: that Gossip Girl is exciting because it contains a very deep understanding of what adolescence is like: She understands that children are a pleasure-seeking species, and that adolescence is a delicious last gasp…of rightful selfishness and cluelessness. Sentences like this are especially powerful in book reviews (and discussions of cultural artifacts more generally), because they’re implicitly making an argument about what literature can do—it can teach us more about the human condition—and explicitly making an argument about what this work of literature can do.

Open with intense relatability (A.O. Scott)

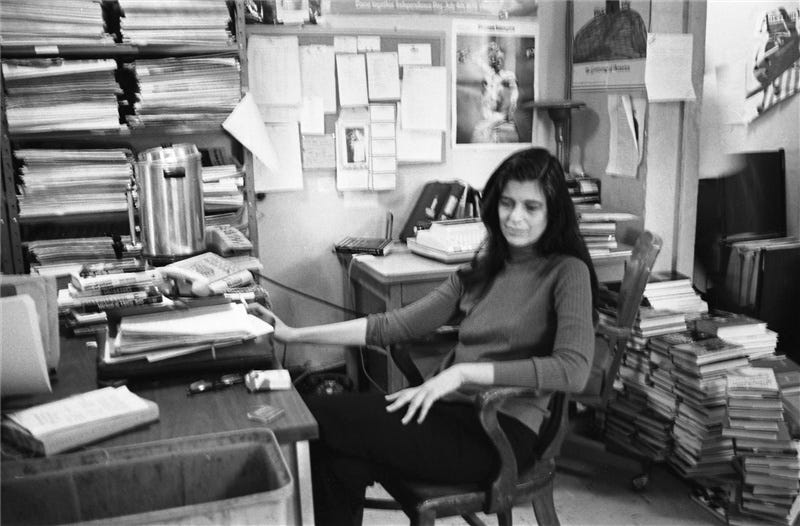

One of the deepest gifts that a writer can offer readers is the feeling of being truly seen, understood, and valued. One of my favorite examples of this is A.O. Scott’s ‘How Susan Sontag Taught Me to Think,’ which opens with a description of Scott as an adolescent that felt so familiar—like he was describing my own anxieties and aspirations:

I spent my adolescence in a terrible hurry to read all the books, see all the movies, listen to all the music, look at everything in all the museums. That pursuit required more effort back then, when nothing was streaming and everything had to be hunted down, bought or borrowed. But those changes aren’t what this essay is about. Culturally ravenous young people have always been insufferable and never unusual, even though they tend to invest a lot in being different — in aspiring (or pretending) to something deeper, higher than the common run. Viewed with the chastened hindsight of adulthood, their seriousness shows its ridiculous side, but the longing that drives it is no joke. It’s a hunger not so much for knowledge as for experience of a particular kind. Two kinds, really: the specific experience of encountering a book or work of art and also the future experience, the state of perfectly cultivated being, that awaits you at the end of the search. Once you’ve read everything, then at last you can begin.

Furious consumption is often described as indiscriminate, but the point of it is always discrimination. It was on my parents’ bookshelves, amid other emblems of midcentury, middle-class American literary taste and intellectual curiosity, that I found a book with a title that seemed to offer something I desperately needed, even if (or precisely because) it went completely over my head. “Against Interpretation.” No subtitle, no how-to promise or self-help come-on. A 95-cent Dell paperback with a front-cover photograph of the author, Susan Sontag.

It’s a useful technique to open with I statements—they’re inviting! and most people, I think, are intrinsically interested in other people—but the power of Scott’s I statements is that they immediately become less about him as a person, and more about a type of person. And maybe you’re this type of person, someone with an intense urge to read all the books, see all the movies, listen to all the music, look at everything in all the museums.

The next sentence, where Scott develops that theme (That pursuit required more effort back then, when nothing was streaming), seems like it will be about the changes that technology and algorithms and platforms have wrought on society. But Scott anticipates that reading—his essay was published in 2019, when readers were likely to expect that approach—and sidesteps it in the next sentence: But those changes aren’t what this essay is about.

Doing so, of course, makes the reader ask: Well, what are you going to write about? The negation creates anticipation. What Scott does next is elaborate on this type of person he’s constructed—critically, but with compassion: Culturally ravenous young people have always been insufferable and never unusual, even though they tend to invest a lot in being different — in aspiring (or pretending) to something deeper, higher than the common run. It would be easy for Scott to dismiss and disown his younger self, and others like him. After all, he writes, such people are always insufferable and never unusual, even though they…[aspire]…to something deeper, higher than the common run). But here, when we think Scott is going to attack the pretensions of this person, he shifts into a gentler tone: Viewed with the chastened hindsight of adulthood, he acknowledges, their seriousness shows its ridiculous side, but—and this is a very important pivot!—the longing that drives it is no joke.

The second paragraph moves from this observation to setting up the real subject of the piece: Susan Sontag, and the influence that Sontag had on Scott. Scott is a great critic, and Sontag a great writer. But in general, I don’t think that most readers open a magazine (or a laptop screen) and think, What I’d really like to do today is read about some guy’s opinions on some writer, neither of whom I have met. The great skill of this opening is that Scott is not just some guy; he’s someone with the deeply relatable experience of being a young person trying to become more culturally fluent in the world. And Sontag is not just some writer, she is the person that guided him in that quest.

Open with a principled hot take (Charlotte Shane)

Nothing is more thrilling—and more intoxicating—than an essay that opens with an incendiary take. By which I mean: an essay that opens with an energetic assault on certain people, practices and ideas, an assault that is executed with such style and forcefulness that you can’t help but agree. It works best, of course, when the argument is worth the fireworks.

One of the best essays I’ve read in this vein is Charlotte Shane’s ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ for Bookforum. Subtitled ‘Power, shamelessness, and sex in Washington, DC,’ it opens like this:

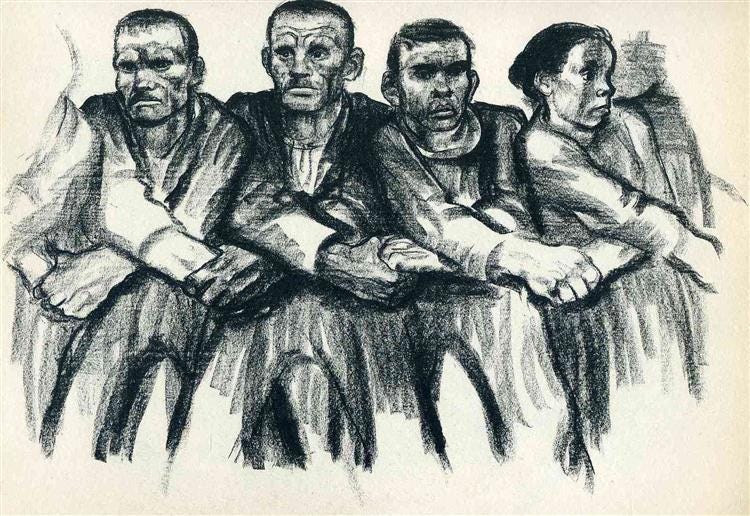

People with institutional power are pathetic. We are not supposed to say it; the official story is that political power, in men at least, is glamorous, alluring, thrilling—the ultimate aphrodisiac. Yet anyone who cares to look will see the truth hanging out as plainly as an unclothed emperor’s…belly. When not momentarily appeased by an outrageous amount of luxury and bootlicking, aspiring kings and kingmakers prune in a bath of pettiness and paranoia that leaves them selfish, dishonest, and cruel. It is not inspiring. It is not admirable. But, like many repulsive states, it can, regrettably, exert an erotic pull.

There may be no better place to observe this ugly phenomenon than the capital of the United States, where government contractors amass garages full of sports cars they can’t be seen driving and people are so desperate to escape their self-loathing that, for years, the District has held the country’s highest percentage of “excessive,” “heavy,” and “binge” drinkers. (The CDC’s terminology shifts over time.) DC’s prominent figures usually obtain their stature through inheritance, ruthless manipulation, venality, or a combination of all three. Accordingly, they earn only a craven imitation of respect, and their dim awareness of this unsatisfying bargain sparks more sadism. The hideous, aggrieved egos of once unpopular kids who now feel that they’re part of an elite (and the equally hideous, congenitally entitled egos of pampered prep-school grads on the cusp of receiving their God-given due) thrive within Supreme Court appointees and low-level nobodies alike. Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but it turns out that even thimblefuls of power can have the same effect.

The first paragraph of Shane’s essay has the forceful, declarative energy that the phrase ‘opening salvo’ was made for. People with institutional power are pathetic—we’re one sentence in, and it feels as if we’ve walked into a gunfight. We are not supposed to say it, Shane continues (which has the effect of making me feel an instantaneous respect for Shane, who is saying it), because the official story is that political power, in men at least, is…the ultimate aphrodisiac. Shane confronts this flattering image by unveiling an emasculating, embarrassing image of reality: Yet anyone who cares to look will see the truth hanging out as plainly as an unclothed emperor’s…belly. When not momentarily appeased by an outrageous amount of luxury and bootlicking, aspiring kings and kingmakers prune in a bath of pettiness and paranoia that leaves them selfish, dishonest, and cruel.

After those 4 sentences—precise and cruel—Shane shifts to short, staccato sentences: It is not inspiring. It is not admirable. Part of the technical excellence of this opening is how Shane varies her sentence length; 1 opening sentence that is crisp, sharp, and easy to read; 3 longer sentences (the second even deploys a semicolon and em dash); and then 2 short sentences that, coming after the linguistic complexity of the previous ones, give the reader a bit of a reprieve. And they sustain our alertness; they help us continue. The last sentence of the opening paragraph (But, like many repulsive states, it can, regrettably, exert an erotic pull) seems to double back, injecting Shane’s pitiless critique with some complexity. The powerful are pathetic and repulsive, and yet—they remain, somehow, compelling.

The second paragraph shifts from power in the abstract and gives us a concrete site: Washington, DC. Here, the specificity of Shane’s observations (government contractors amass garages full of sports cars they can’t be seen driving) makes this paragraph entertaining and even more cutting. There’s a velocity to this paragraph, as Shane characterizes the hideous, aggrieved egos of America’s politicians, ending with this devastating remark: Absolute power corrupts absolutely, but it turns out that even thimblefuls of power can have the same effect.

Three ways to begin, in personal essays

The essays below (by Alyssa Battistoni, Lucy Grealy, and Andrew Solomon) begin by introducing us to a person and a situation. They efficiently and discreetly give context, like time and place, and set up the central problem of the essay—the struggle that the person is engaged in, and why it matters.

Open with what you didn’t know or understand (Alyssa Battistoni)

I’ve reread Alyssa Battistoni’s ‘Spadework,’ from n+1’s spring 2019 issue, many times since it was first published. From the start, you see that Battistoni’s essay will have the stakes and narrative intensity of a really great story. (It’s helpful for me to think of personal essays as stories: they have characters, settings, plots; their endings should make the entire piece feel whole.)

In many stories, the protagonist starts off not knowing or understanding something; through their (usually difficult) experiences, they arrive at a new, hard-won way of seeing the world. Here’s how Battistoni begins:

In 2007, when I was 21 years old, I wrote an indignant letter to the New York Times in response to a column by Thomas Friedman. Friedman had called out my generation as a quiescent one: “too quiet, too online, for its own good.” “Our generation is lacking not courage or will,” I insisted, “but the training and experience to do the hard work of organizing — whether online or in person — that will lead to political power.”

I myself had never really organized. I had recently interned for a community-organizing nonprofit in Washington DC, a few months before Barack Obama became the world’s most famous (former) community organizer, but what I learned was the language of organizing — how to write letters to the editor about its necessity — not how to actually do it. I graduated from college, and some months later, the global economy collapsed. I spent the next years occasionally showing up to protests. I went to Zuccotti Park and to an attempted general strike in Oakland; I participated in demonstrations against rising student fees in London and against police killings in New York. I wrote more exhortatory articles. But it wasn’t until I went to graduate school at Yale, where a campaign for union recognition had been going on for nearly three decades, that I learned to do the thing I’d by then been advocating for years.

The first paragraph of Battistoni’s essay contains many useful, conventional techniques. Start with a specific scene. Give just enough context (In 2007, when I was 21 years old). Include quotes or dialogue. She uses these techniques to describe a young person with strong convictions: Our generation is lacking not courage or will…but the training and experience to do the hard work of organizing…that will lead to political power.

What happens next? The second paragraph begins with a confession: I myself had never really organized. Battistoni explains where her convictions came from (a internship, occasional attendance at protests and demonstrations), but she also describes how inadequate those experiences were: what I learned was the language of organizing—how to write letters to the editor about its necessity—not how to actually do it. Through these details, we’re beginning to understand some of the broader themes of the essay: youthful naiveté, a desire to do good and change the world, the uncertainty and mysteriousness of how to actually do so. As she runs through examples—Zucotti Park, a strike in Oakland, demonstrations in London and New York—it feels as if there’s something accelerating, something moving forward.

It’s the last sentence of the second paragraph that gathers together all of this material to establish the story of the essay, the story that we will read next: But it wasn’t until I went to graduate school at Yale, where a campaign for union recognition had been going on for nearly three decades, that I learned to do the thing I’d by then been advocating for years. It feels right to have this explained here; at this point, I understand her previous experiences and convictions, and I feel invested in her story. And part of the investment comes from understanding that this isn’t just about Battistoni; it’s also about the particular moment in history created by Occupy Wall Street and police brutality protests and graduate student unionization.

Open with an eccentric personal behavior (Lucy Grealy)

I took an online class last year with the writer and editor Nadja Spiegelman (who edited the much-loved Astra Magazine). One of the great rewards of the class was being introduced to the memoirist Lucy Grealy’s 1993 essay ‘Mirrorings,’ which later became her critically-acclaimed memoir Autobiography of a Face.

The essay, subtitled ‘A gaze upon my reconstructed face,’ begins:

There was a long period of time, almost a year, during which I never looked in a mirror. It wasn't easy, for I'd never suspected just how omnipresent are our own images. I began by merely avoiding mirrors, but by the end of the year I found myself with an acute knowledge of the reflected image, its numerous tricks and wiles, how it can spring up at any moment: a glass tabletop, a well-polished door handle, a darkened window, a pair of sunglasses, a restaurant's otherwise magnificent brass-plated coffee machine sitting innocently by the cash register.

At the time, I had just moved, alone, to Scotland and was surviving on the dole, as Britain's social security benefits are called. I didn't know anyone and had no idea how I was going to live, yet I went anyway because by happenstance I'd met a plastic surgeon there who said he could help me. I had been living in London, working temp jobs. While in London, I'd received more nasty comments about my face than I had in the previous three years, living in Iowa, New York, and Germany. These comments, all from men and all odiously sexual, hurt and disoriented me. I also had journeyed to Scotland because after more than a dozen operations in the States my insurance had run out, along with my hope that further operations could make any real difference. Here, however, was a surgeon who had some new techniques, and here, amazingly enough, was a government willing to foot the bill: I didn't feel I could pass up yet another chance to "fix" my face, which I confusedly thought concurrent with "fixing" my self, my soul, my life.

One of the perils of being a Proust reader is that you start to see a bit of Proust in everything. In the cadence of the first sentence (There was a long period of time, almost a year…) I can’t help but think of the beginning of In Search of Lost Time, which begins: For a long time, I went to bed early (in Lydia Davis’s translation) or For a long time, I would go to bed early (in the Moncrieff/Kilmartin/Enright translation). But this might just be my reading of it.

But—if I’m trying to be more objective—what the first sentence does is explain an eccentric behavior: I never looked at my face. The next 2 sentences explain how difficult this was in practice: This wasn’t easy…I began by avoiding mirrors, but by the end of the year I found myself with an acute knowledge of the reflected image. The first paragraph is only 3 sentences long; much of the length comes from the last sentence, which describes the many mirror-like surfaces where Grealy might catch her reflection: a glass tabletop, a well-polished door handle, a darkened window, a pair of sunglasses, a restaurant's otherwise magnificent brass-plated coffee machine sitting innocently by the cash register.

These are lovely, satisfyingly specific images. But the sheer number of them is also creating a subtle bit of suspense: it seems like it’s actually quite hard to avoid her reflection! So why is she doing so? It could be a tragically common—and therefore ordinary—level of body dysmorphia. But the second paragraph makes it clear that there is something specifically difficult for Grealy, more so than other women. Here she does a bit more context-setting: At the time, I had just moved, alone, to Scotland and was surviving on the dole; and before that, I had been living in London, working temp jobs. Now the story is situated in time and space. And she starts offering details—a plastic surgeon; nasty comments about her face that hurt and disoriented her; more than a dozen operations in the States—which start to sketch out the problem in her life, and how severe it is.

By the end of the second paragraph, we understand the setup: that she is in Scotland so she can see a specific plastic surgeon, and she thinks of this as her potential salvation. The last sentence has a certain awkward grace to it—it’s quite long, but the beginning helpfully summarizes what’s going on (Here, however, was a surgeon who had some new techniques, and here, amazingly enough, was a government willing to foot the bill) and why it matters to Grealy. I didn't feel I could pass up yet another chance to "fix" my face, which I confusedly thought concurrent with "fixing" my self, my soul, my life.

What I admire about this line is that, although Grealy’s experiences are extremely specific (we learn in the next few paragraphs that she was diagnosed with jaw cancer from a young age, which left her with a disfigured face), she is gesturing at a universal human experience. It’s common, I think, to feel that some specific thing about you must be fixed—and only then will you be good enough, only then will your life go well.

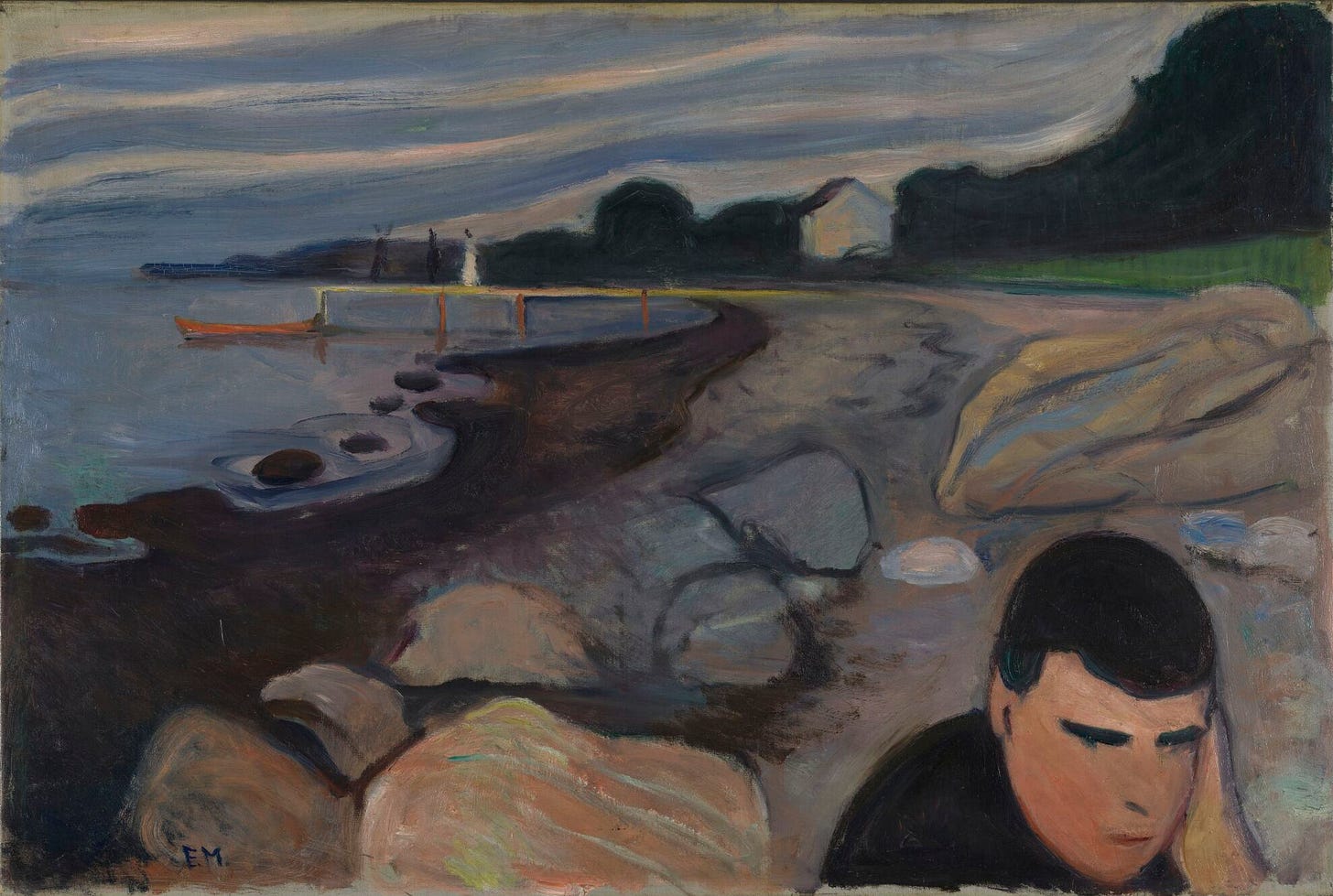

Open with a contradictory mystery (Andrew Solomon)

One way to create an instantaneous feeling of tension—a mystery that the reader must solve, by continuing onwards—is to point out something contradictory and hard to explain. That’s how Andrew Solomon’s remarkable ‘Anatomy of Melancholy,’ published in 1988, begins:

I did not experience depression until I had pretty much solved my problems. I had come to terms with my mother’s death three years earlier, was publishing my first novel, was getting along with my family; had emerged intact from a powerful two-year relationship, had bought a beautiful new house, was writing well. It was when life was finally in order that depression came slinking in and spoiled everything. I’d felt acutely that there was no excuse for it under the circumstances, despite perennial existential crises, the forgotten sorrows of a distant childhood, slight wrongs done to people now dead, the truth that I am not Tolstoy, the absence in this world of perfect love, and those impulses of greed and uncharitableness which lie too close to the heart—that sort of thing. But now, as I ran through this inventory; I believed that my depression was not only a rational state but also an incurable one. I kept redating the beginning of the depression: since my breakup with my girlfriend, the past October; since my mother’s death; since the beginning of her two-year illness; since puberty; since birth. Soon I couldn’t remember what pleasurable moods had been like.

I was not surprised later when I came across research showing that the particular kind of depression I had undergone has a higher morbidity rate than heart disease or any cancer […] Attempting to understand this strange malady, I plunged into intensive research shortly after my recovery. I started by attempting a coherent narrative of my own experience.

The first line (I did not experience depression until I had pretty much solved my problems) sets up the mystery. We’d expect someone to feel depressed if their life was going poorly. But, as Solomon explains, there were good things in his life (publishing my first novel; had bought a beautiful new house, was writing well) and difficulties that he was able to overcome (my mother’s death three years earlier; had emerged intact from…a two-year relationship). After presenting this evidence, he uses the 3rd sentence to summarize: It was when life was finally in order that depression came slinking in and spoiled everything.

The rest of the paragraph has a slow, reassuring rhythm. It helps that the longest sentences are lists, with a legible structure to them. There’s the list of painful realizations that still, to Solomon, offered no excuse for his depression—and there’s some gentle humor here, when Solomon goes from perennial existential crises, the forgotten sorrows of a distant childhood (which might understandably distress someone) to slight wrongs done to people now dead, the truth that I am not Tolstoy (which suggest an exaggerated negativity). The second-to-last sentence is also a list, where Solomon tries to identify potential beginnings for his despair: since my breakup with my girlfriend, the past October; since my mother’s death; since the beginning of her two-year illness; since puberty; since birth (more tragic exaggeration!)

The second paragraph deftly uses the personal (I was not surprised later) to move to the societal (when I came across research showing that the particular kind of depression I had undergone). After elaborating on some details, which I’ve omitted, Solomon ends by writing: Attempting to understand this strange malady, I plunged into intensive research shortly after my recovery. I started by attempting a coherent narrative of my own experience.

The introduction has accomplished a very useful goal: we what this essay is going to be about. It will tell us about Solomon’s depression and recovery, and also give us a broader societal view.

Three recent favorites

“All media is training data” ✦✧ A celebratory winter recipe ✦✧ Janet Malcolm’s collages

“All media is training data” ✦

I’ve been fascinated by the artist and composer Holly Herndon for years. She’s done some incredibly interesting projects with music and machine learning/AI—like a machine learning model, developed with her husband Mat Dryhurst, trained on Herndon’s voice. As she told the New Yorker in 2023,

“I’ve never really fetishized my voice…I always thought my voice was an input, like a signal input into a laptop.” Holly+ can use a timbre-transfer machine-learning model to translate any audio file—a chorus, a tuba, a screeching train—into Herndon’s voice. It can also be used in real time or be fed a score and lyrics: last year, Herndon gave a TED talk that opened with a recording of Holly+ singing an arrangement by Maria Arnal, a Catalan musician. It was a performance Herndon could never do. “These beautiful, melismatic runs—you have to study that stuff for years,” she said. (She also does not speak Catalan.) Several months later, Herndon released a track in which Holly+ covers “Jolene,” by Dolly Parton. It’s glitchy, with oddly placed breaths and slurred phrases, and is weirdly compelling. A free version of Holly+ is available online. When I uploaded a clip of sea lions barking, it returned a grunting, stuttering, portentous motet.

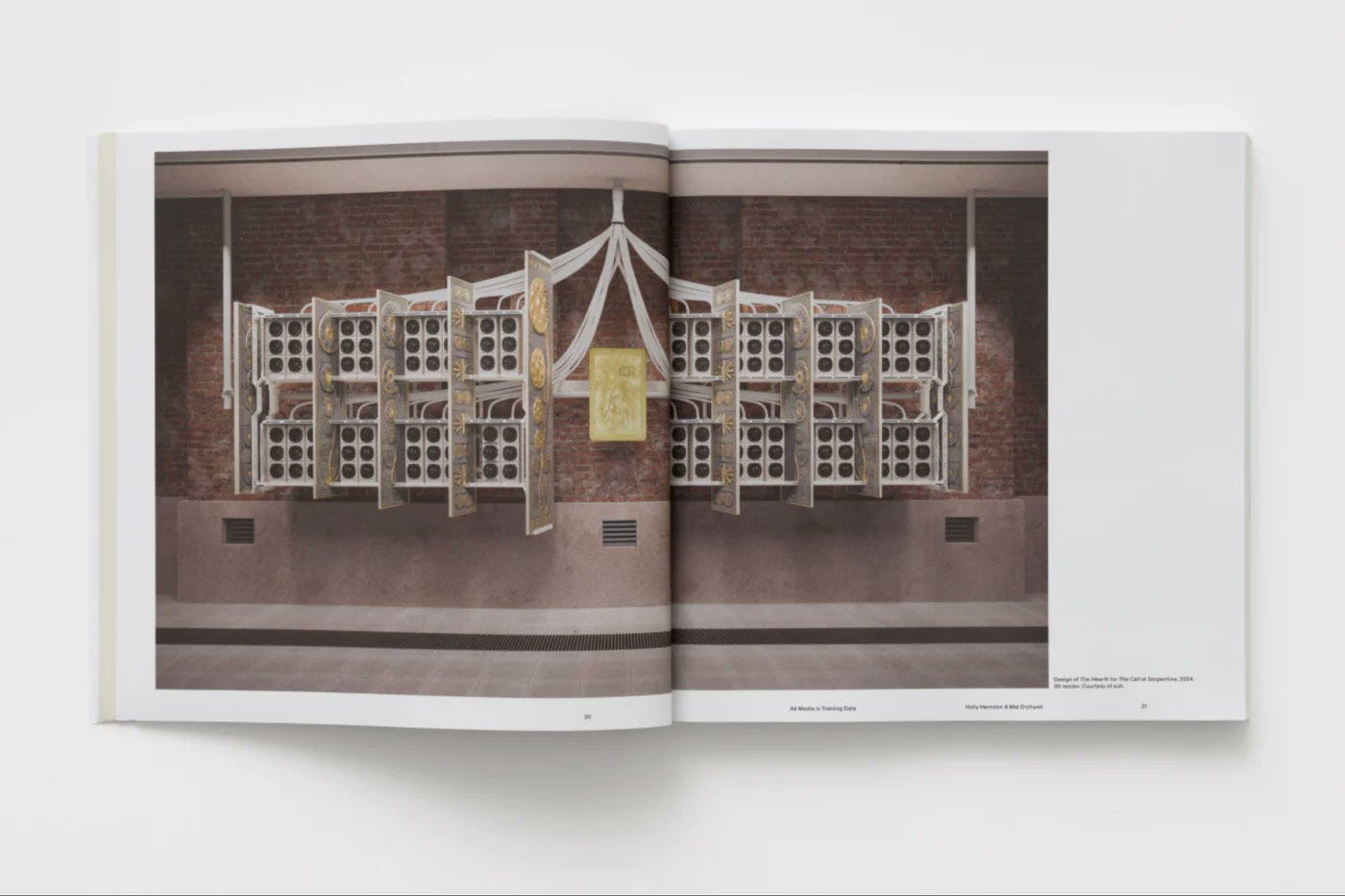

To accompany Herndon and Dryhurst’s latest solo exhibition in London (open until February 2), the Serpentine has published a book titled All Media is Training Data that includes their work alongside essays by the theorist Benjamin Bratton, the journalist Liz Pelly (whose book Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist came out this month), and others.

I’m really trying to not buy too many books this month—but I think I will get a copy of this one, which is beautifully designed by Eric Hu. The title, by the way, is from Herndon’s proposition that “If all media is training data, including art, let's turn the production of training data into art instead.”

For more of my thoughts on AI art, read—

A celebratory winter recipe ✦

Last weekend, I stayed in and made Meera Sodha’s beetroot, walnut, and smoked tofu claypot noodles. The beetroot/walnut combo feels very earthy and cozy in the winter. I really recommend this recipe—it takes an hour and a half, but about 40 minutes are just waiting (I read a book while standing next to the stove), and the result is really special and flavorful. And it’s vegan!

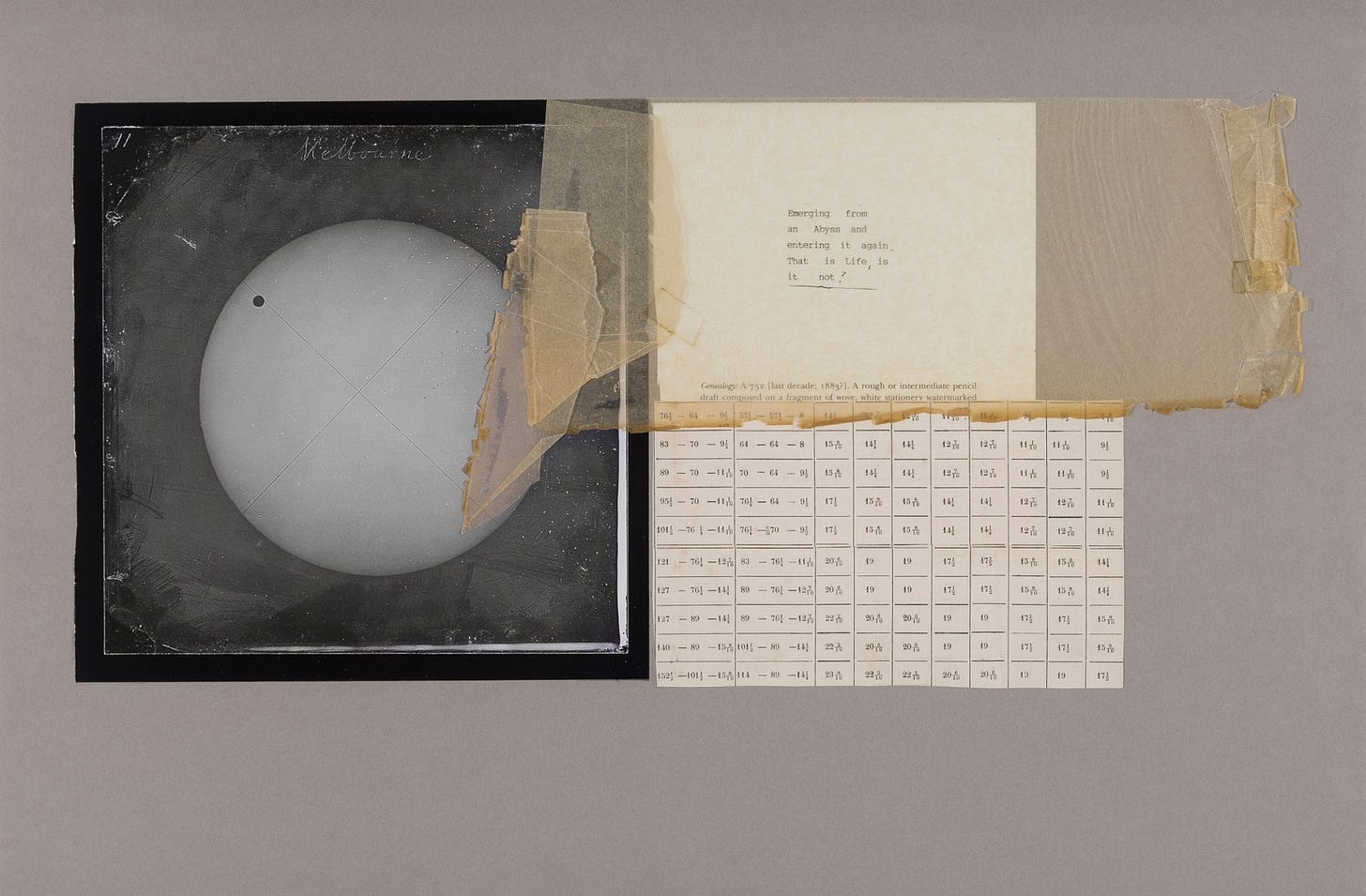

Janet Malcolm’s collages ✦

I’m currently reading Janet Malcolm’s Forty-One False Starts (which includes her essay on Gossip Girl), and the opening essay—where Malcolm profiles the painter David Salle—includes a brief mention of Malcolm’s collages.

Malcolm was, of course, a peerless journalist and writer. But it’s exciting to see people like her experiment in other disciplines, too! I enjoyed this Artnet article on her collages and photographs, and Austin Kleon’s blog post on her bookmark collages using paper ephemera.

Thanks for reading, as always, and I hope your January resolutions (to read more, write more, take greater pleasure in life, and so on…) are going well!

I’m paraphrasing; I can’t remember exactly what either of us said!

This was really helpful to the beginners who wants to dabble in writing essays. 👌🏼

Wonderful wonderful piece, Celine. I find copying to profound too because it unlocks a creativity found through another mind, — which for someone just starting out, is immensely beneficial. Hemingway (who I'm not the biggest fan of if we're being honest here) started out by copywriting Steins' The Making of Americans, after all, and that book's singular prose comes through in his prose. He took the lessons with him, clearly.

An additional resource that I've found to really enjoy is https://www.typelit.io/

though, I will say, it doesn't quite beat sitting with an essay or a book that you truly admire and rewriting it by hand or verbatim into a word doc.