good artists copy, ai artists ____

not anti-AI, not pro-AI, but a secret third thing ✦ and 13 propositions for AI as an aleatory art

For Charli XCX fans, this summer is (or was) brat summer. But for San Francisco technologists and venture capitalists, it’s felt more like generative AI’s coming-of-age summer. The tech slowdown seems to have skipped over generative AI—I keep on meeting VCs investing in the area, and startup founders speaking rapidly and urgently about “multimodal AI models.” Generative AI can grow up to be anything! It can be an artist, journalist, novelist, economist or scientist! Its future is full of possibilities—vague, unrealized, but deeply exciting possibilities.

And then, of course, I log on, and scroll through post after post about why AI will destroy art, literature, culture, society, and human existence—or why AI is fake, overhyped, expensive, unreliable, and pointless. I have too much humility (or too little specialist knowledge, perhaps) to pick a side.1

But I’m interested in these questions, and especially the question of AI’s impact on art. Unfortunately, 80% of AI art writing suffers from 1 of 2 problems:

The people who understand AI don’t understand (or truly value) art and literature

The people who do understand art and literature, in turn, don’t really understand AI—and are deeply fearful of it, hostile, or both

Exceptions exist, such as Sofian Audry—the new media artist and scholar who also worked in Yoshua Bengio’s deep learning lab in the early 2000s. Audry is willing to take the aspirations of AI researchers and artists seriously, and in late 2021, they wrote a book about what art in the age of machine learning might look like. AI art was a nascent discipline: There weren’t too many people writing hot takes about AI art then, but there were still artists exploring what was possible: Holly Herndon (musician), Anna Ridler (visual artist), and Lillian-Yvonne Bertram (poet).

In late 2022—a year after Audry’s book came out—ChatGPT was launched. Its immense popularity is what really made the possibilities of AI accessible to the general public, and has kicked off a greater reckoning with the artistic possibilities—and consequences—of the technology. A lot of AI art created right now isn’t that great, to be honest. It struggles with people’s faces—but it’s getting better all the time. Most of the outputs are shameless derivatives of existing works—but I think that says less about generative AI, and more about a very human tendency towards the familiar.

I genuinely think we’re in the early days of understanding how artists, musicians, and writers might use generative AI. It’s an emerging technology, and it takes time to see how a technology ends up reshaping artistic practices and purposes. (The historian Lois Rosson, in an essay for Noema last year, notes that many conflicts around AI art echo 19th-century debates about photography’s potential for art.)

So in this post, I’ll try to follow Audry’s example and write about what it might mean to make art with generative AI. This won’t be a how-to, and it won’t be specific to any models or products we have today. What I want to do, instead, is focus on:

What art is (and isn’t), and whether the artist can really be “replaced” by AI

What AI art can learn from Fluxus, an interdisciplinary art movement of the 1960s–70s that included figures like John Cage, Yoko Ono, and Nam June Paik—and embraced chance, uncertainty, and new technologies

And 13 propositions for what AI, as an art form, can offer in art, music, and literature

I’m writing this as someone with a professional interest in AI (I’m a software designer) and a personal interest in art (I read Sternberg Press books for fun). And, frankly, I’m writing this as a frustrated reader. Generative AI is not an uncomplicated, straightforwardly good thing for art, culture, and creativity—but it’s also not, I think, an obviously bad and useless technology for artists.

Back in 1959, the British physicist and novelist C.P. Snow lamented what he saw as the “two cultures” of intellectual life: STEM on one side, the arts and humanities on the other, both refusing to take the other seriously. These two cultures have, for the most part, developed two opposing narratives about AI.

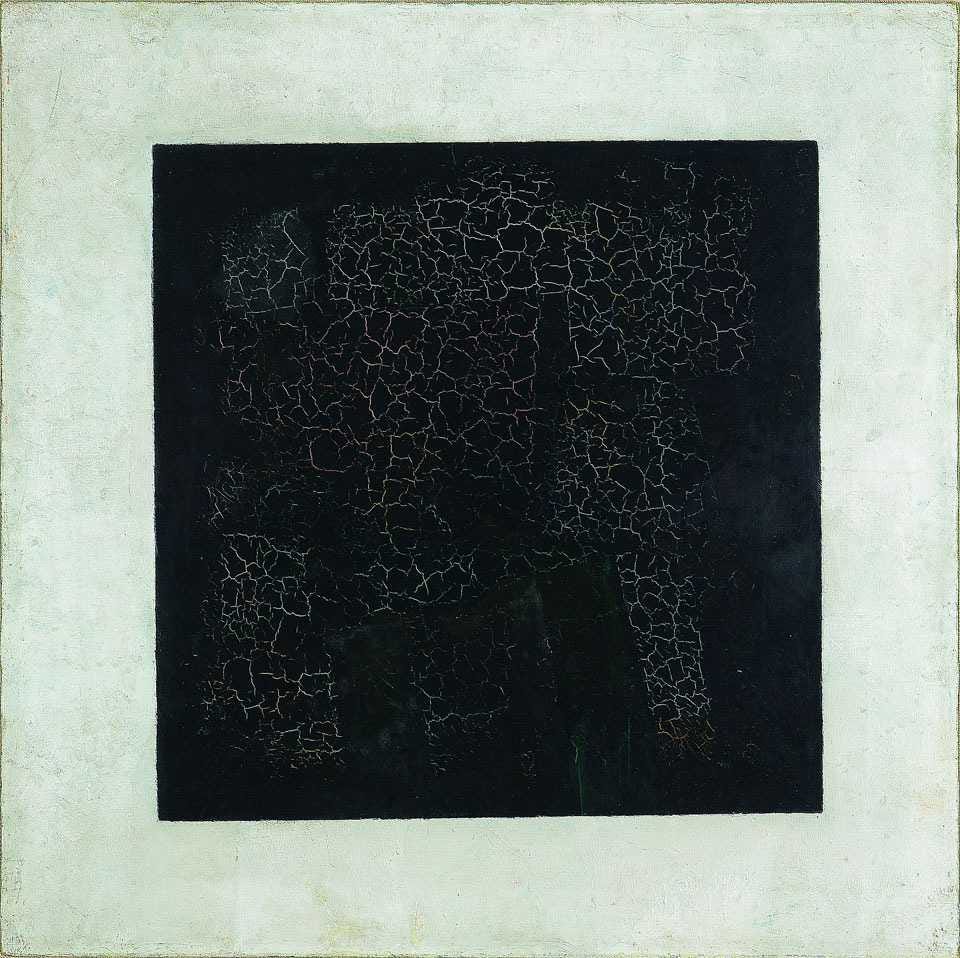

But as someone who thinks that Norbert Wiener (the cybernetics guy who theorized about “black boxes”) and Kazimir Malevich (the art guy who painted the Black Square) are both useful figures to know about…well, I’d like to find a way to think about AI from a technological and humanistic perspective.

What I won’t be discussing: the ethics of collecting data and training models; copyright and ownership; automation and labor and job loss; existential risk; the environmental consequences of AI. These topics are necessary parts of the debate around generative AI art—they’re just not my focus today.2

What is (and isn’t) art

Much of the writing that addresses questions like Can AI create art? Will AI replace artists? assumes that the writer and reader have a shared understanding of what art is. But—for reasons I’ll explain below—this assumption means that the people who answer Yes or No are talking about completely different kinds of art, and not really understanding each other.

So let me propose a somewhat crude distinction between 2 kinds of art:

Art consumed as a commodity, or used to sell a product. For many people, these kinds of works might not qualify as “art” at all, because they’re not intended to create an autonomous aesthetic experience. Their aesthetic qualities are often subservient to a functional purpose. This category of art includes:

An illustration made for a company’s marketing blog, where the intention is to just have some image, any image to draw the reader in. While the illustrator may have more serious ambitions for their work, the client is often indifferent to it. They just need an image because people click links with images

A stock photo of a generic object—a lily?—intentionally created to be repurposed in another visual work

A portrait serving a straightforward functional purpose (corporate headshot, wedding photos), retouched in generic ways (lens correction, white balance)

Marketing copy for a new beauty brand’s product page, software release announcement, &c

Royalty-free “lo-fi chill beats” for a YouTuber to put in their video

Art that isn’t consumed but experienced aesthetically. These artworks have the capacity to alter our perceptions: of ourselves, certain concepts, the history or present or future of the world. Many of my favorite visual artworks reorient my perception of beauty (making a beautiful thing boring, making an ugly thing interesting); many of my favorite literary artworks change my perception of morality (by depicting the outcomes of invisible injustices, perhaps) or time. These works are more culturally ambitious, and has a certain amount of cultural agency: It can intervene with the world and change it, and change us. I use agency deliberately here—as the historian Ron Richardson writes about object agency, we don’t just “use” objects in the world; “we too are changed by the objects we engage with.” This category of art includes:

An editorial illustration made for the cover of The New Yorker, or a painting included on the cover of the NYRB, where the emphasis is on expression, meaning-making, and interpreting a concept or feeling in a visually memorable way. The artist is encouraged, even expected, to have a distinctive style and approach

A photograph by Wolfgang Tillmans of lilies in a plastic water bottle, instead of a vase—where the goal isn’t simply to depict these objects neutrally, but evoke something through their juxtaposition (why aren’t the lilies in a more conventionally beautiful vase?)

A portrait photograph by Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, or Nan Goldin. All 3 depicted LGBTQ subcultures at a time when being visibly gay/queer, or deviating from existing gender norms, was poorly understood and highly stigmatized

Ambient music by Brian Eno, which—like the royalty-free lo-fi chill beats—are meant to be background music, but are also a statement that Eno is making about what music is/isn’t/can be

The distinction here is between art as commodity and art as cultural agent. Think commercial art versus fine art. Copywriting versus literary writing. The same type of thing (illustration, photograph, paragraph, song) can aspire to different purposes.

Art as commodity

When people claim that AI can “replace artists,” they’re often relying on the first definition of art. “Art,” in these contexts, is a decorative adornment that serves a clear, functional purpose. The artist is more easily replaced with another, similarly skilled artist. For that reason, it’s not a stretch for pro-AI people to believe that the artist can be replaced with AI.

My own stance on this, for what it’s worth, is a bit more skeptical. I think we will see the deskilling of certain forms of art labor—certain tasks will become easier and cheaper to do with AI, and the job functions that focused on that will become increasingly precarious, or be eliminated all together.3 Graphic designers will use AI to generate things like “drone photo, white background” instead of buying images from Shutterstock. Self-published authors will use AI to generate “futuristic cyberpunk neo-Tokyo book cover” and skip the graphic designer entirely. And CEOs and execs are already trying to replace in-house copywriters with AI. But in the short term, it feels premature to wholesale replace these roles with AI. Illustrators and copywriters do not just make images and produce text—they help people understand what they’re asking for and what the goal of the image or text is. They align stakeholders! In many jobs, what people deliver is less important than how they deliver it.

I sometimes feel like AI can do that is the 2024 version of looking at a logo design, or an ad campaign, and going, I could have made that. But the ability to technically reproduce an existing work is not the same as having the ability to bring that work into being.

In “Graphic Design Criticism as Spectator Sport,” the renowned graphic designer Michael Bierut writes about spending 2 years trying to help UPS with a brand redesign. The company was afraid of change, and Bierut—and 2 other design agencies, it turns out—never managed to sell the client on a redesign.

Four years later, however, a different agency succeeded in redesigning UPS’s logo. As Bierut writes,

Was it better than the logos we had presented? Not necessarily. But Futurebrand had done something that we and the others had failed to do: they had convinced the client to accept their solution.

The basic starting point of Graphic Design Criticism as a Spectator Sport is "I could have done better." And of course you could! But simply having the idea is not enough. Crafting a beautiful solution is not enough…you still have to go through the hard work of selling it to the client. And like any business situation of any complexity whatsoever, that process may be smothered in politics, handicapped with exigencies, and beset with factors that have nothing to do with design excellence. You know, real life.

What Bierut is saying about design applies to many art-as-commodity situations. Today, the role of a human is to a) make the thing, and b) handle the organizational and interpersonal complexity that results whenever you collaborate with others. AI doesn’t solve that problem, and is likely to increase that complexity in unexpected ways. You can’t really replace a worker without changing all of the processes that they’re involved in.

And if catastrophic job losses and increasing economic inequality happen, it is not—strictly speaking—something that AI itself is doing. It is something that humans do with AI. “Technology,” the historian Melvin Kranzberg famously observed, “is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”4 The impact that new technologies have on society is shaped partly by intrinsic qualities of the technology itself, but partly (maybe even mostly) by the human values around it.

Art as aesthetic experience

When people claim that AI will never be able to make real art and replace artists, they’re usually focused on art that is experienced aesthetically—art that changes our perceptions.

One such work is the experimental composer John Cage’s 4’33”, which is intended to change the audience’s perception of sound. Unlike most musical scores, the score for this work instructs performers to not play any instruments for 4 minutes and 33 seconds. A performance of 4’33” can feel like a provocation—a challenge to our preconceived notions of what music should be like.

The work comes out of Cage’s belief that the distinction between silence and sound, music and not-music, was arbitrary—silence is never really silent; and any auditory stimulus can be experienced as music, even if it’s not intentionally created by a trained musician. Someone who experiences 4’33” might, afterwards, have a totally different perception of silence, and a renewed attentiveness to ambient sounds that were previously ignored or undesired.

Works like this alter our perception of the world, and alter the culture around an art form, because they respond to what’s come before in a novel and unexpected way. It’s hard to imagine AI coming up with an idea like this, for two reasons:

It’s not in the training set. AI’s strength and weakness (in many cases, something’s fatal flaw is intimately associated with its greatest strength) is that it riffs exceptionally well off of what’s come before. But while Cage’s 4’33” had precursors—other compositions had used long passages of silence—the concept of an entirely silent piece was still fairly original. Generative AI tends towards certain aesthetic motifs that dominate the dataset, and it takes real effort to produce something strikingly divergent.

It involves unexpected domain transfer. It’s not even clear that Cage was familiar with some of the obvious precursors, like a composition by Alphonse Allais that included 24 empty measures. But Cage was deeply influenced, throughout his career, by an entirely different domain: Zen Buddhism. In the art curator Alexandra Munroe’s words, Cage had a “conception of Zen as a technique to activate perception,” and through works like 4’33”, he advanced the idea that art could be “a catalyst for direct insight into nature, consciousness, and being.” By asking audiences to be receptive to the supposed emptiness of silence, he was also asking audiences to experience reality in a fresh, unmediated way, and to notice how their consciousness responded to the sounds of the world.

Humans are, I think, naturally interested in this kind of domain transfer—applying spiritual revelations into the creation of experimental music. While many artists agree that you need some knowledge of a field’s history in order to do radical work (learn the rules in order to break them), some level of domain transfer might allow someone to create formally radical and innovative artworks, even if they haven’t consumed the entire canon of their discipline. But AI seems to function in the opposite way: It requires large amounts of training data (although many researchers are trying to develop more economical models), and it’s hard for models to adapt their knowledge to substantially new domains.5

Works like this also have the capacity to change us, as we make them. As Cage once wrote, “Our business in living is to become fluent with…life…and art can help this.” And elsewhere: “Art…is not self expression but self alteration.” Artmaking isn’t just something we do for the outcome; it’s something we do for the process, which includes the process of becoming the person with the taste, knowledge, sensitivity, agency, and ambition to produce the outcome. The most revelatory experience of art may come from the making, not merely the experiencing.

In a recent post, the writer Venkatesh Rao proposed a taxonomy of different kinds of “creators.” There are two modes of writing, he suggested: writing instrumentally and writing metaphorically. “Instrumental words,” Rao writes, “try to change the world in predictable ways, while acquiring some sort of legible extrinsic reward.” Instrumental artmaking is what I’ve described above—art that acts as a commodity, that is meant to perform a predefined function. But the kind of writing that Rao is most interested in is writing that functions as metamorphosis:

Metamorphic words…attempt to change the author in unpredictable ways, which you can think of as an intrinsic reward of sorts…If you don’t like, or are bored with, who you are right now, whether as a writer, or more generally as a person, you can write yourself into an unpredictable new version. It’s a kind of disruptive self-authorship lottery.

Human existence is characterized by a perpetual dissatisfaction, a divine discontent, with who we are now, and what our world looks like now, compared to what it could be. Change is unpredictable; we rarely know how things will turn out in the end. But we still invite it, still seek it out.

Artmaking is, for many, an essential part of enacting these changes. As long as we desire to change ourselves and our reality, we will continue to create art. AI might be our companion in this effort, a useful and invigorating collaborator, but it is not capable of changing us alone. We need to actively participate and author that change.

For previous writing on changing ourselves, in unpredictable ways—

Stealing Fluxus ideas

I have great faith in humanity’s continued interest in art as an aesthetic experience and cultural agent of change, and it’s hard to imagine people automating away those things. But artists have always used new technologies in unexpected, expressive ways, and it’s likely they’ll do the same with AI.

In thinking about what artists might do with AI, I keep on returning to Fluxus, the art movement that began in the 1950s and saw Cage as the “spiritual father of Fluxus.” The Fluxus movement included artists, poets, composers, and musicians, and many of their works are clearly informed by Cage’s approach to composition.

I mentioned a few other Fluxus artists—Mieko Shiomi, Nam June Paik, and Alison Knowles—in an earlier post! Scroll down to the “Five recent favorites”:

My interest in Fluxus led me to Chance, a book edited by Margaret Iverson and part of MIT Press’s Documents of Contemporary Art series. I love this series—and wrote about it in an early newsletter post—and the insights it offers on contemporary artmaking are especially relevant to AI art.

There are 4 ideas from Chance—largely drawn from Fluxus artists like John Cage, Yoko Ono, and George Brecht—that suggest some interesting directions for AI art:

AI as an aleatory art

The flaws of the medium become its signature

Prompt engineering as performance art

Psychoanalyzing the corpus of human knowledge

Below, a discussion of these ideas—and a tentative manifesto for what AI art should be.

AI as an aleatory art

The term aleatory refers to anything dependent on random or stochastic processe (like rolling a die, or using the result of a random number generator). Thanks to the avant-garde composer Pierre Boulez, the term was often used in the 20th century to describe art that used chance to create, produce, or perform a work.

One of the most famous examples of aleatory musical composition is John Cage’s Music of Changes, where he used the I Ching, a Chinese divination text, as a random number generator to determine the duration of particular sounds, and the tempo of the music, and other qualities. But the Fluxus artists sought to use aleatory approaches in nonmusical ways, as well. “The methods of chance and randomness,” the artist George Brecht wrote,

can be applied to the selection and arrangement of sounds by the composer, to movement and pace by the dancer, to three-dimensional form by the sculptor, to surface form and colour by the painter, to linguistic elements by the poet.

I’d like to propose that we think of generative AI as a technique for producing aleatory artworks. Much of the angst around AI, to me, comes from observing the stochastic, indeterminate, unpredictable nature of it—and framing these things as flaws. But in aleatory art, these qualities are useful and productive: They invite the artist to produce works through different processes, which lead to different aesthetic outcomes.

The art historian Dario Gamboni, in an essay for Cabinet, describes chance as “a creative ally.” It’s common, Gamboni notes, for conversations about chance in art to be “limited by the habits of binary or dualistic chance…the implicit expectation to find only chance or, instead, no chance.” Discussions of AI in artmaking, I’d argue, are limited by the same binary thinking: Either the AI is doing all of the art, or it’s doing none of it. It may be more fruitful to think of the artist’s agency and the AI’s contribution along a more spectrum—the artist can gently or firmly guide the AI to produce an artwork.

Using chance—however much or little the artist chooses—is still, in Gamboni’s words, characterized by

the search for, or the welcoming of, a foreign intervention that promises or imposes an unknown and unexpected result. This is the case whether a metaphysically transcendent quality is attributed to this foreign character or not, and it accounts for the centrality of the use of chance in the movements dedicated to the pursuit of innovation and in twentieth- and twenty-first-century art at large.

The flaws of the medium become its signature

Thinking of AI as an aleatory art might allow us to see the problems of generative AI in a new light. Many attempts to use generative AI are hindered by the following problems:

Generative AI often gets things wrong

It has unexpected outputs that can feel deeply unsettling

It’s unexplainable

These qualities can make generative AI useless, frustrating, and sometimes deeply concerning in many business contexts. For artists, however, I’d argue that each of these flaws offers exciting artistic possibilities.

What if we thought of AI as producing fictions that are evoked by reality, but not exclusively derived from reality?

What if we sought out that unexpectedness, and saw it as a tendency that could be harnessed to create divergent, novel aesthetic experiences?

While decisions made in a corporate or governmental context might prioritize explainability, do we really need it in art and aesthetic experiences?

Explainability has become a central preoccupation for AI critics and ethicists, but as the journalist Dan Davies notes in The Unaccountability Machine (which I discovered through Henry Farrell’s fascinating essay “Seeing Like a Matt”), explainability is not just a problem with AI. We already have an explainability problem with faceless bureaucracies and organizational policies that might make life-changing decisions—denying someone coverage for a particular healthcare problem, say—with no ability to explain how that decision occurred and how to appeal it.

And when it comes to AI, it’s not clear that explainability can actually be prioritized alongside other AI ambitions:

The dream of AI research is still of the prospect of ‘getting out more than you put in’…‘explainability’, for all that it’s seen as an important ethical goal, is practically a contradiction in terms when applied to a system that you also want to see as intelligent…

[T]here’s no real magic to an ‘artificial intelligence’ if it is explainable in this sense. The process of explanation is intrinsically demystifying – it’s the means by which you explain how the conjurer put the rabbit into the hat and then pulled it out.

But the possibility of something like real magic is a huge part of the attraction of AI. The dream has always been to create a machine that can come up with original thoughts, have ideas that its creators couldn’t predict and can’t explain.

Obviously this can be ethically fraught and deeply concerning. But there are other places in which a certain level of mystification and unexplainability is deeply appealing to us. In art, I don’t always need to know how the artist created something, and how the artwork functions. The core obligation of the artwork is to move me, not to make itself legible to me.

There are other, smaller flaws with AI art, of course: The unrealistic faces, the jerky motions, the occasional plunge into uncanny-valley territory. But for those flaws, I can’t help but think of a much-quoted passage from the musician Brian Eno’s A Year with Swollen Appendices, a diary and essays from 1995:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit — all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided. It’s the sound of failure: so much modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar sound is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.

One contemporary example of this, with digital technology and art, is the intense nostalgia people have for the crudely ugly aesthetic of 1990s GeoCities websites. Many of those websites were archived and commemorated through One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age, a project run by the artists Olia Lialina and Dragan Espanschied.

As web technologies became more expressive and powerful, the crude qualities of these early websites—the limited typefaces, unsophisticated layouts, and details that were considered unprofessional (glittering GIFs, custom cursors)—were replaced by sleeker, “better” website designs. As Lialina writes in her influential essay “The Vernacular Web,” the “web of amateurs [was] soon to be washed away by dot.com ambitions, professional authoring tools and guidelines designed by usability experts.”

But now that websites can look better than this, many web designers are—as Eno predicted—cherishing and emulating the GeoCities aesthetic. The Gossip’s Web directory, created by the artist and programmer Elliott Cost, has hundreds of examples of websites made in the last few years that intentionally evoke the qualities that were “weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty” about early websites. I suspect that the flaws of today’s generative AI models will, eventually, be seen with a similar level of nostalgia.

Prompt engineering as performance art

At this point, I should probably explain what first made me connect Fluxus with AI art. Earlier this year, I took a class with the artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed, who introduced me to the Fluxus artist George Brecht and his event scores—which, as I’ll explain below, have some enticing similarities with AI prompts.

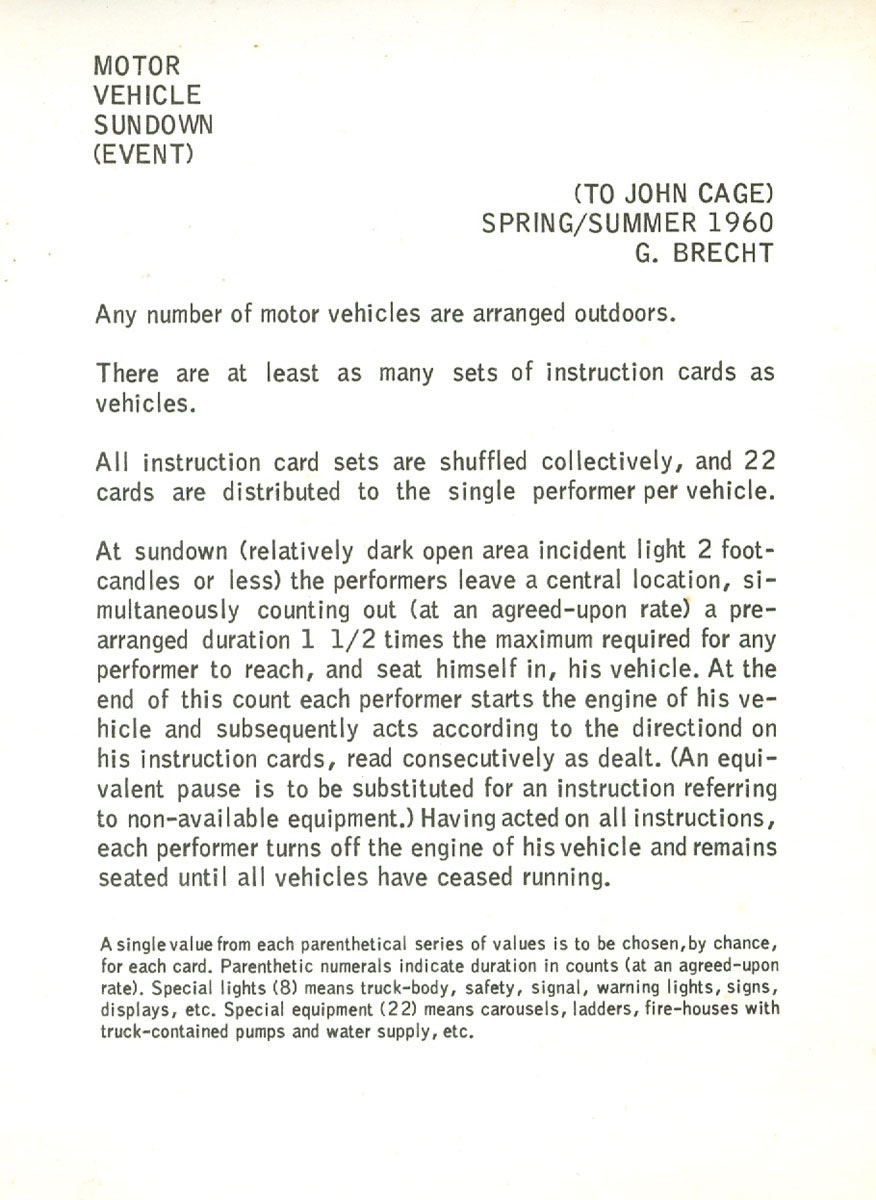

George Brecht was an avant-garde composer and conceptual artist who, after studying with John Cage, developed the concept of an event score. Event scores were instructions to perform certain actions in a loosely specified manner. Here’s an example from one of Brecht’s most well-known event scores, Motor Vehicle Sundown (1960).

The score requires some number of performers (the exact number is unspecified), who each operate a vehicle for the piece. Each performer is given a set of 22 randomly assigned cards from a deck, and is then asked to perform the instructions in order. The instructions looked something like this:

“Parking lights on (1–11), off”

“Sound siren (1–15)”

“Strike hand on dashboard”

—where the numbers in parentheses represented a range of numbers that the performer could pick from. Picking 5 meant that the action had to be performed for 5 seconds.

To me, Brecht’s event scores are strikingly similar to the prompts one might give to a generative AI model. An event score is a text, created by an artist, that can have multimodal outputs.

More broadly, event scores and other conceptual art–like works separate the intention of a work with its execution—a separation that feels quite similar to how we might separate a prompt from an output in AI, or a program from a particular execution.

In Fluxus, the intention of a work began with the event score created by the composer or artist. The score acted as a “template,” as Julia Robinson wrote in ArtJournal, that loosely defined the possible outcome. Because the scores included intentional flexibility (like the number ranges) or unintentional ambiguity, different performers and contexts would lead to different aesthetic outcomes.

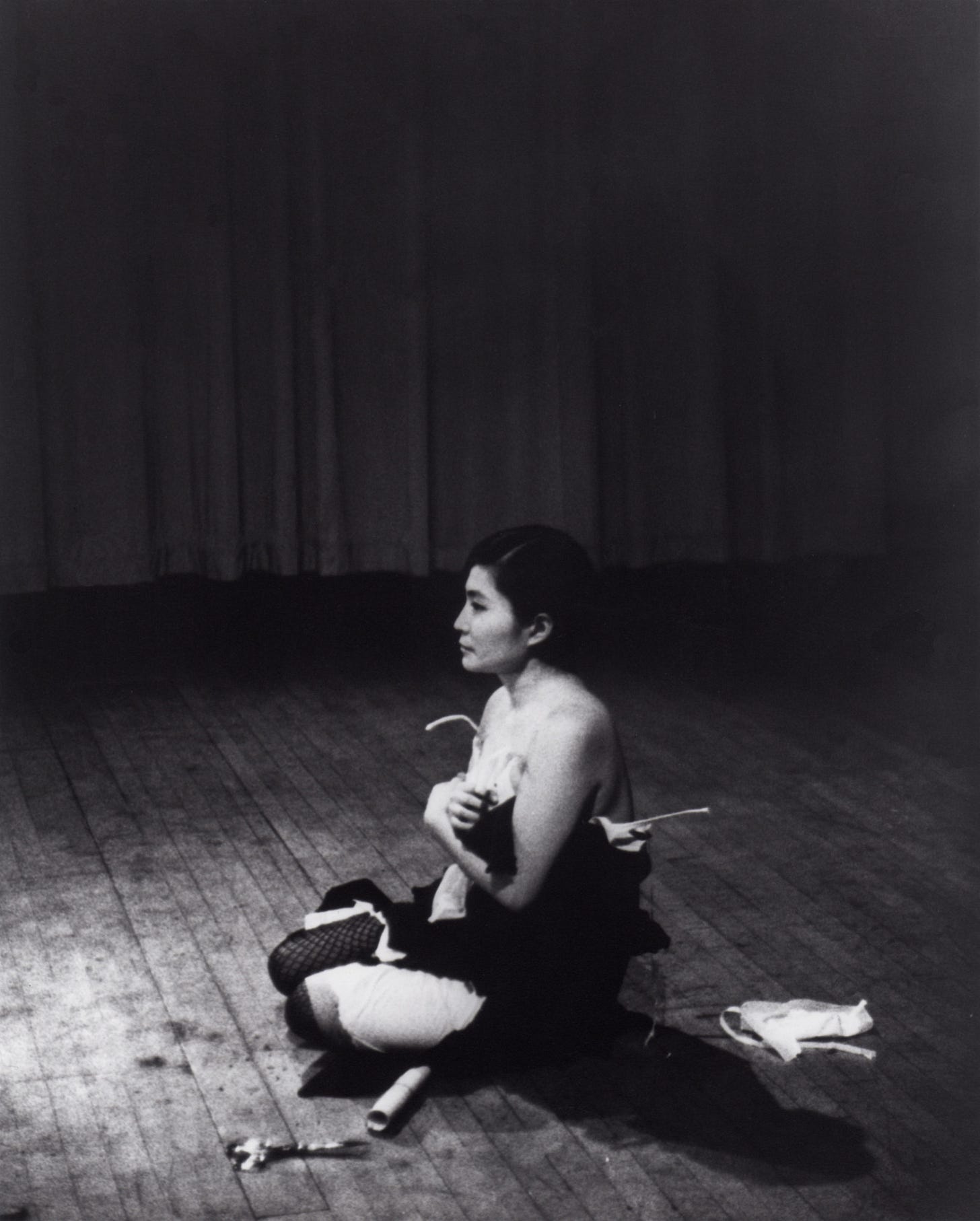

An event score was often treated as an artwork unto itself. “The early Fluxus scores,” the art historian Alexandra Munroe wrote, “were characterized by clarity and economy of language…They could be performed in the mind as a thought, or as a physical performance before an invited audience.” The artist Yoko Ono, who along with Brecht was one of the first to “experiment with the event score and its conceptual language as a form of art,” was thrilled by the possibilities of treating instructions as art, and inviting others to realize the artwork by executing the instructions:

I think painting can be instructionalized…[an] artist…will only give instructions or diagrams for painting…The painting starts to exist only when a person followed the instructions to let the painting come to life.

Ono’s enthusiasm was so great that, in May 1962, she exhibited a collection of instructions for paintings—without any actual paintings. It was, Ono said later, '“one of the most exciting moments of my life. It was great! It was fresh! It was a revolution!”

The cultural historian Jacquelynn Baas offers some examples of Ono’s most significant instructional works. There’s the evocatively described Water Piece (1964):

Steal a moon in the water with a bucket.

Keep stealing until no moon is seen on the water.

—and her earlier Secret Piece (1953):

Decide on one note that you want to play. Play it with the following accompaniment:

The woods from 5 a.m. to 9 a.m. in summer. [98]

“The only sound that exists to me,” Ono said in a 1966 lecture, “is the sound of the mind. My works are only to induce music of the mind in people.”

But Ono did execute some of her instructions, including the well-known Cut Piece (1964). The separation between the description and execution, however, is profoundly compelling.

In generative AI, perhaps we can think of the prompt as an artistic piece itself, where the artist articulates a class or template of possible works. An AI model could then be a specific performer, and the output it offers—in response to the prompt—is a particular instantiation, today’s performance, of the work.

The prompt as the artistic piece, generic class of possibilities, and then the AI output as a particular instantiation—the performance, the output, but only in this particular moment.

Some final thoughts on prompt writing and engineering:

After a lovely conversation with the singer and music scholar Ty Bouque recently (who I met through Substack!), I’ve started to think of the interaction between a human and AI model as a form of structured improv. It’s a conversation in which the prompter doesn’t know how the AI model will respond. And continuing the conversation means that both parties (the human and the AI) are committed to responding and building on top of the other’s actions.

The Chance book includes an interview with the Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles, whose statements are usefully applied, I think, to AI art. On authorship: “I try to distance myself from a pathological approach to the artwork (As something only the artist can produce). I prefer to imagine pieces that can be made by anyone at any time.” On instructions: “There is a similarity between [my] instructions and musical notation. One day I’d like to make instructions so perfect that a piece could be accurately reproduced.”

The book also includes an interview with Brian Eno, who describes his fascination with the avant-garde composer Cornelius Cardew, who was also influenced by Cage. (It seems as if all experimental musicians of the 20th century interacted with Cage’s ideas in some way!) Cardew’s approach, as Eno describes it, was to

suggest a set of rules and conditions, which are actually the piece of music, and then an individual performance is one possible outcome of those rules and conditions…Instead of building a house…it is like designing a seed. You plant it and it grows into something.

Cardew’s work gave Eno the idea that “an artist didn’t finish a work but started it. design the beginning of something, and the process of releasing the work is the process of planting it in the culture and seeing what happens to it.”

Psychoanalyzing the corpus of human knowledge

While Iverson’s book Chance primarily focuses on Fluxus artists, she touches on other art movements of the 20th century that incorporated chance events—including surrealism. For the surrealist André Breton, chance occurrences,

by virtue of their apparently fortuitous, accidental character, bypass one’s consciousness and intentionality, thereby giving access to an otherwise inaccessible reality.

But what seems accidental and entirely spontaneous is, to the psychoanalyst, a potential sign of a deeper, submerged logic at work. As Iverson writes:

The unconsciousness is an interference apparatus that produces slips of the tongue, mistakes, sudden failures of recall, and so on…In [psycho]analysis all these mistakes can supposedly be interpreted as having unconscious intentions, so they are not really mistakes at all.

Reading this, I can’t help but think of the mistakes and failures of AI that reveal some kind of insidious bias. Language models that can’t help but repeat, compulsively, racist or sexist beliefs. We, the conscious and civilized humans teaching AI to be a productive member of society, can’t help but react with fear to these outputs. So we try to fix the problem—we ask the AI to repress the racism and sexism and other biases that it has learned from its training data, from its context.

For many, the biased output of generative AI is a problem. But it’s a problem that reveals the structure of society and culture. The responses that a generative AI model gives us can reveal the unconsciousness of humanity, society, and the archives—and sometimes, what’s in our collective data unconsciousness is horrible! It reveals the traumas that we think society has “gotten over” or dealt with, long ago; it reveals the compulsive repetitions and reenactments of the past.

I’m interested in what we might learn—and the kind of art we might create—if we approach AI’s flaws from a psychoanalytic point of view. Psychoanalysts often see subconscious tendencies—especially the negative ones—as rich with information and context. That’s certainly true of AI; biased outputs tend to reveal the structure of society’s biases. We perceive, in a synthesized aggregate form, how the history of images tends to exclude certain faces (or depict them in consistently flawed ways); how certain people’s words were and weren’t recorded.

We shouldn’t uncritically incorporate those biases into AI artworks, but we also can’t easily avoid them. If we take the psychoanalytic tradition as a guide, we may decide that these biases can’t be fully repressed—they’ll show up in unexpected and destructive ways. What if we accepted their presence and instead created art that tries to engage with, understand, and process those biases?

13 propositions for AI as an aleatory art

If you’ve made it this far, I hope you’re somewhat open to (or maybe even excited by!) how artists might use AI to create aleatory art and conceptual art. The history of art has always been shaped by new technological possibilities and processes. While most of the AI art I see today isn’t especially ambitious nor aesthetically significant (for my tastes, at least), I also believe that it’s possible to create great art with AI. And it’s already happening.

So I’ll close, now, with a kind of tentative manifesto. Here are 13 propositions for how artists can use AI:

Meaningful art requires total authorship. In 2022, the technologist and VC Diana Kimball Berlin wrote about the concept of total authorship in generative AI. Total authorship, Berlin writes, “means end-to-end responsibility for a creative work, with a single human imagination making every meaningful decision along the way.” Total authorship could look like the machine learning artist Anna Ridler’s approach to Mosaic Virus (2019), where Ridler assembled her own dataset (by taking 10,000 tulip photographs), hand-labeled them, and then created video art installations using the data. Ridler’s process, she wrote, was meant to convey that “[t]here is always a human decision…[when] using AI.” But total authorship doesn’t have to be this labor-intensive. Artists can use preexisting datasets and models for their work—but they have to accept artistic responsibility for how this shapes the possible artworks produced.

Meaningful art requires material literacy and technical fluency. In physical art and design disciplines, practitioners are encouraged to develop the material literacy required to fully understand and express their aesthetic intentions. An artist creating ceramic pieces, for example, can be more expressive if they understand the material qualities of the clay and glazes they use; how a kiln works; how the firing process transforms the physical substances they rely on. For generative AI, material literacy might require developing sufficient technical fluency in how AI works. An artist that uses premade models has a more limited range of expression than an artist that can train their own. Luckily, many of the tools required to work with AI are getting more accessible all the time—and there’s more and more educational material online. In middle school, I taught myself basic graphic design and web design skills through sites like Abduzeedo, Tutsplus, A List Apart, and Stack Overflow. What are the equivalent sites for aspiring AI artists?6

AI art should embrace disciplinary fluidity. One of the interesting things about AI (especially as multimodal input and output become more sophisticated) is that an artist who’s technically fluent in AI might be able to bootstrap—or partially replace—the need for traditional literacy in a particular domain. I’m quite good with Photoshop (2D raster graphics) and decent in Illustrator (2D vector graphics); I know basically nothing about video editing. But generative AI models might allow me to repurpose some of my existing knowledge to generate short films. That said, I don’t think AI will entirely replace the need for basic aesthetic fluency—the best prompts for AI image generation generally exhibit a fluency with basic photographic terms (depth of field, double exposure) or cultural references (cyperpunk, Escher-like, Ghibli-like). And I suspect my generated short films will be significantly worse than if I had a deep understanding of film history, theory, and practice.

Use chance to escape conscious control and let go of unnecessary constraints. Art often requires agency, intentionality, and control. But total control and intentionality can be exhausting, especially since it fences you into your current tastes, predilections and tendencies. “As you go on,” the conceptual artist (and gifted teacher) John Baldessari once said,

you get better and better at making things look good, and you have to set up stumbling blocks so that you can escape your own good taste, and even that creeps in a lot.

By escaping your own tastes, you might end up with something usefully novel and exciting. The German artist Gerhard Richter saw chance as “essential” to his artistic practice:

[Chance] destroys and is simultaneously constructive, it creates something that of course I would have been glad to do and work out for myself…I now see it as…something entirely positive.

Constraints create the voice. Chance—especially the kind of chance offered by generative AI—adds some useful stochasticity and unexpectedness to the artistic process. But an artist never fully surrenders to randomness; inevitably, the artist creates certain constraints through the prompts entered and the elaborations offered. In 1966, the artist Allan Kaprow wrote that:

After all the shock of playing around with chance operations wears off, they seem much like using an electronic computer: the answers are always dependent on what information and biases are fed into the system in the first place. If dullness is built in, the chances are that dullness will come out.

The use of chance, Kaprow insisted, “is a personal act,” and inevitably revealed the ambition or laziness of the artist using it. John Cage “has gone to elaborate lengths” to make music which seems to disavow Cage’s intentional control. And yet: “the music is always recognizably Cage and often of very high quality. Others, imitating his approach, sound exactly like imitators and their work is dead.” When an artist uses chance procedures, they may not be the author of the output. But they become the author of the system that produces the output. (In AI art, the system could simply be the conversation that produces an output—but it could also be the conversation and the fine-tuned model and the training data.) And that system can create dull art—or deeply exciting, transformative art.

The process is the art. The idea that I’m most excited by, from Fluxus event scores and 20th century conceptual art, is that art is not just about the work. It can also be about the process of creating the work and documenting how it happened. In 1969, the sculptor Robert Morris said in “Notes on Sculpture, Part IV: Beyond Objects” described how exhausted he by art that was merely the “craft of tedious object production.” He was interested, instead, in art that centered “chance, contingency, indeterminacy—in short, the entire area of process.” The focus on process, Morris wrote,

refocuses art as an energy driving to change perception…What is revealed is that art itself is an activity of change, of disorientation and shift, of violent discontinuity and mutability, of the willingness for confusion even in the service of discovering new perceptual modes.

Why is process so interesting? Perhaps because it shifts the emphasis away from the artwork as a standalone object, and recontextualizes art as a human process, where human intentionality and intention is present throughout—even if chance procedures and artificially intelligent agents are used to create the object. The poet David Jhave Johnston’s ReRites (2017–8) is a particularly useful example of incorporating the process into the art. Every morning, Johnston generated some text and then created screen recordings of him editing the output, carving down the raw slab of machine-generated text into a more intentional form. The resulting texts became a box set of books, which were exhibited in a space alongside the videos.

The biases are the art. Contemporary artists often use their works to interrogate how various archives (defined as collections of historical records, often formal/institutional) shape our understanding of history and the present. Art about archival practices often draws attention to the biases present—like the people whose words are absent from the archives (because they were illiterate, perhaps, or their experiences were assumed to be historically insignificant and irrelevant). AI art could do the same. In the poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s A Black Story May Contain Sensitive Content, Bertram generated texts using 2 different models: GPT-3, and GPT-3 trained on texts by the renowned Black poet Gwendolyn Brooks. The output reveals the different conceptions of Blackness and race that each model has learned from its data.

The framing is (increasingly) also a part of the art. When you look at a Rembrandt painting, it’s easy to feel that the authenticity and allure of the artwork rests in the object. It’s hard to fake that level of skill, and it’s deeply impressive to observe. How will this change with AI, given its potential to generate faithfully imitative new Rembrandts and convincing deepfake photographs?7 My guess is that authenticity and allure will no longer reside in the object, but in the framing. To assess authenticity, we’ll look at everything around the object (the metadata, if you will). Who published this work? Who disseminated it? What’s the story behind this work? How plausible and compelling is that story? Similarly, the allure of the work will come from the entire experience—not just the artwork, but the process, the documentation…and the persona, too, of the artist. All this will contribute to a certain mythology around the art and invest it with meaning and value. Brian Eno has an intriguing take on this in A Year with Swollen Appendixes. Part of an artwork, Eno argues, is the “frame” constructed around it. The frame is

the world surrounding the work – the thoughts, assumptions, expectations, legends, histories, economic structures, critical responses, legal issues and so on and on.

In music, Eno suggests, the frame—which includes a musician’s approach to fashion, lifestyle and publicity—has typically been seen as subservient to the music itself. But, Eno asks, “Who said music should be at the centre of the experience?” What’s considered worthy of artistic attention, Eno notes, is itself an artistic decision. For AI, perhaps this means that a single image will no longer be asked to bear the entire weight of an artist’s intentions. Instead, the artist might present an AI-generated image along with documentation about their process of data collection, training, fine-tuning, and so on. (This is essentially what Bertram and Ridler did when sharing their AI artworks.)

AI will shift what is easy/hard to accomplish, and thereby shift what is artistically interesting/boring to create. When mass-produced perfection becomes easy, artists, designers and craftspeople often respond by creating works that have intentional roughness, sloppiness, and imperfection. Handmade ceramics that are unevenly shaped or glazed. Digital photos with noise and lens distortions added. As AI gets better at generating hyperrealistic deepfakes, I suspect that some artists will respond by creating intentionally low-fidelity, more gestural, loosely detailed works. Which brings me to:

“Realism” is not the goal, it’s a tool. What was hard to accomplish (crisp, high-fidelity photorealism) will become cheap and unremarkable to produce. Technical excellence alone will not create a great artwork, and photorealistic output is just one of many options for artistic expression.

Truly singular aesthetic experiences will become possible. I keep on thinking about Brian Eno’s observation that, prior to the invention of the record, “every musical event was unique: music was ephemeral and unrepeatable, and even classical scoring couldn’t guarantee precise duplication.” The record changed this, by capturing a specific performance into an analog storage medium, allowing people to hear a performance “identically over and over again.” Records helped people access more musical experiences—but those experiences were never unique. “It’s possible,” Eno wrote in 1995,

that our grandchildren will look at us in wonder and say, ‘You mean you used to listen to exactly the same thing over and over again?’

Gary Hustwit’s documentary Eno, released earlier this year, is a brilliant way of subverting this in film. Hustwit collaborated with the technologist Brendan Dawes to create a system that generates a new version of the Eno documentary for each screening. The system draws from hundreds of hours of footage to create a 100-minute film, so each screening is essentially unique. This concept can be easily applied to other domains, like music (which Eno has explored) and literature.

Meaning is created by the receiver/audience/culture, not (just) by the artifact and creator. In many ways, this proposition extends the idea that The process is the art. Certain Fluxus artworks were presented in an incomplete state. Brecht’s event scores, and Yoko Ono’s pieces, were intended to stand alone as text-based artworks. But they could also be enacted by people, and a new artwork—a combination of the written score and a specific performance of it—would emerge. In generative AI, perhaps the artist can create a system that responds to the user’s interactions, accepts the user’s own prompts, and then creates an artwork that is partly authored by the artist, and partly by the audience.

Be receptive to the unexpected. Unpredictable outcomes are not a problem, they’re the point of AI as an aleatory art. I’m drawn to what Eno has said about the unpredictability inherent to Fluxus event scores:

The unpredictability of the outcome…is what makes the conceptual couple [of] instructions/performances fascinating: this uncertainty gap between the imagination of how the piece should be or should look and…the various interpretations…For Fluxus artists, everything was about intention and misunderstanding.

And, in the introduction to Chance, Margaret Iverson perfectly captures what is exciting about aleatory processes, and their potential to destabilize and defy our intentions.

It would, of course, be unbearable if our intentions were regularly frustrated. Yet there is something terribly arid, not to say mechanistic, in the idea of a world where all our purposes result in predictable consequences, where we are completely transparent to ourselves and where intentions always result in expected actions. We value the degree of interference in human intentional activity offered by the unconscious, by language, by the…computer, by the instruction performed ‘blind,’ In short, we desire to see what will happen.

One final thought. I wrote this because there seems to be a mutual disdain between the “AI people” and the “arts/humanities people.” Unfortunately, I don’t really feel at home on either side. I couldn’t pick a side in the wordcels versus shape rotators debate of 2022, either, as someone simultaneously committed to:

Rotating shapes (in my head, but also in Figma)

And rearranging words (in my head, but also in the Substack editing interface)

This newsletter is mostly about literature and culture, but I don’t see these interests as separate from my interest in tech—especially since our experience with literature and culture is constantly being transformed by technology.

Four recent favorites

My favorite deepfake ✦✧ The limits of data and defining “good art” ✦✧ Where’s the 21st century version of Bell Labs? ✦✧ Yu Su’s newest track

My favorite deepfake ✦

My favorite AI-generated images from last year were @seoulthesoloist’s Himalayan Ambient images, which appeared to show Buddhist monks setting up some synthesizers at the top of a mountain, and then settling in for a peaceful ambient music session.

The images are low-resolution, and the usual AI artifacts (bulbous, strangely articulated hands, arms that meet the body in anatomically uncanny ways) are present—but there’s still something delightful about these images to me! When these images were shared on Twitter and Tumblr, a number of people responded with sentiments like: I want so badly for this to be real / I wish this were real.

The artistic problem with generative AI, to me, is not that it’s not real enough yet. The problem is that very few people are creating AI imagery that people want to believe in. People will participate in fantasies that are sufficiently evocative and enchanting—erasing, if necessary, the “unreal” parts to make the fantasy more complete.

The limits of data and the definition of “good art” ✦

The philosopher C. Thi Nguyen (who, in a past life, was also a food writer for the L.A. Times!) has a new essay, “The Limits of Data,” published in Issues in Science and Technology. Nguyen offers a very useful way to think about what quantitative data can and can’t do. Data that is easy to aggregate and scale across different contexts, Nguyen notes, is necessarily impoverished—it excludes contextual information that cannot be interpreted outside of that context.

Nguyen’s essay is also relevant to my post because it opens with a funny and tragic example of how ML/AI engineers try to understand art:

I once sat in a room with a bunch of machine learning folks who were developing creative artificial intelligence to make “good art.” I asked one researcher about the training data. How did they choose to operationalize “good art”? Their reply: they used Netflix data about engagement hours.

The problem is that engagement hours are not the same as good art. There are so many ways that art can be important for us. It can move us, it can teach us, it can shake us to the core. But those qualities aren’t necessarily measured by engagement hours. If we’re optimizing our creative tools for engagement hours, we might be optimizing more for addictiveness than anything else. I said all this. They responded: show me a large dataset with a better operationalization of “good art,” we’ll use it. And this is the core problem, because it’s very unlikely that there will ever be any such dataset.

Where’s the 21st century version of Bell Labs? ✦

Our lives are indelibly shaped by certain 20th century technological innovations, like the transistor, cellular telephones, the C programming language, and UNIX. These 4 inventions, and many others, came from Bell Labs.

Bell Labs is one of those improbably productive institutions that exist, here and there, in the history of technology. Members of Bell Labs won 10 Nobel Prizes and 5 Turing Awards. Over at Construction Physics, Brian Potter has written an incredible deep dive into what made Bell Labs so powerful—and why there’s no 21st century version of it. “The world that Bell Labs thrived in no longer exists,” Potter writes. “To push technological progress forward, we'll need to understand both why Bell Labs worked and why it no longer could.”

Yu Su’s newest track ✦

In my second-ever Substack post, I wrote briefly about my love for the experimental musician Yu Su, who was born in Kaifeng and now lives in London:

Yu Su’s newest track, “Avanvera,” opens with low notes and an indistinct, low voice threaded through them—before a shimmering, slow ascent that feels like an monk’s patient hike up a shaded, forested mountain slope.

I’m not good at keeping up with new releases—but I do keep up with the truly delightful newsletter Concrete Avalanche, which features independent and alternative music from China. Here’s the post that brought “Avanvera” to my attention—along with some other electronic, folk, and “dungeon synth” music:

An image from my life enters your screen

I am so, so sorry for this exceptionally long newsletter installment—and thank you for making it all the way here! Things I’ve been up to (besides thinking about Fluxus, conceptual art, and AI):

Actually taking notes on my reading instead of letting the information wash over me (slow reading, I’ve learned, leads to fast writing)

In Barcelona listening to electronic music

In Helsinki celebrating love, friendship, formal attire, and everything beautiful in this world (which is to say: I attended a wedding)

Here’s a photo of me waiting at a bus stop in Helsinki…on my way to see the home of the iconic Finnish architect and furniture designer Alvar Aalto…and eating a Finnish Karelian pie (karjalanpiirakka):

My next post will be the usual everything i read in august: fiction, nonfiction, essays, &c). The post after that will (probably) be about Aalto’s architecture and why I’ve returned from Finland completely ryebreadpilled.

Thank you, as always, for reading this newsletter! I’d love to hear your hot/lukewarm/cold takes on AI art. Wishing you a lovely summer and a beautiful week ahead—

And also, isn’t AI an emerging technology? As in: still emerging? How is everyone so certain? All we can say is that AI is overhyped for now; expensive for now; environmentally damaging for now but also, regrettably, likely to be environmentally damaging in the future.

That seems to be the typical arc of nearly all industrial developments in an insatiable growth-oriented economy—thanks to the Jevons paradox, where improvements in resource/energy efficiency are offset by increased demand, so that technological advances meant to decrease resource usage tend to have the effect of increasing it.

But here are some articles that have stayed with me, re: the problems of generative AI—I’d also be interested in other people’s recommendations!

On the ethics of collecting data and training models—Caroline Hasken’s “The Low-Paid Humans Behind AI’s Smarts Ask Biden to Free Them From ‘Modern Day Slavery’” in Wired, May 2024. The Nigerian-American artist Mimi Ọnụọha’s The Future Is Here!, commissioned by London’s The Photographers’ Gallery in 2019, also depicts the workers that label and annotate data for ML/AI models.

On copyright and ownership—I keep on thinking about a particular AI copyright dispute from 2018, when the French art collective Obvious sold an AI artwork for $350k USD. After the sale, the AI artist and developer Robbie Barrat tweeted that the output closely resembled a neural network he trained and open-sourced. You can read more about this in The Verge (“How three French students used borrowed code to put the first AI portrait in Christie’s”) and Artsy (“What the Art World Is Failing to Grasp about Christie’s AI Portrait Coup”). Of course, there are other contemporary debates around copyright, re: how LLMs have been trained on large swaths of content online (produced by users who see no economic benefit from the technology)…and how text-to-image models can be used to unintentionally—or intentionally—create work that rips off another artist or illustrator.

On automation and labor and job loss—Aaron Benanav’s Automation and the Future of Work (Verso, 2020) is a good broader overview of the history of automation and its economic impacts. (I have to confess: I only read half of it, and that was 4 years ago, so if you’ve read the whole thing, please let me know what you thought…) I also think Astra Taylor’s concept of “fauxtomation” is helpful—in “The Automation Charade” (Logic Magazine, 2018), she describes how automation “is both a reality and an ideology,” and narratives of technological automation can obscure the human labor that is still required, despite new tech and tools.

On existential risk—I’m not going touch this one, lmao. There are 10,000 AI newsletters on Substack, go read their takes on this!

On the environmental consequences of AI—the seminal paper for this is probably Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell, and Angelina McMillan-Major’s “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” (FAccT, 2021). After discussing some recent benchmarks of CO2 emissions from training LLMs, they write that

When we perform risk/benefit analyses of language technology, we must keep in mind how the risks and benefits are distributed, because they do not accrue to the same people…[and] it is well documented in the literature on environmental racism that the negative effects of climate change are reaching and impacting the world’s most marginalized communities first. Is it fair or just to ask, for example, that the residents of the Maldives (likely to be underwater by 2100) or the 800,000 people in Sudan affected by drastic floods pay the environmental price of training and deploying ever larger English LMs, when similar large-scale models aren’t being produced for Dhivehi or Sudanese Arabic?

Deskilling doesn’t have to lead to mass proletarianization of art workers—the technologies that automate some tasks can, simultaneously, offer new art-labor opportunities for people to retrain into.

I briefly looked into some of the historical literature around this when working on a research project about the Jacquard machine and its impact on textile designers in 19th century Britain, and one of the most interesting papers I read was the historian James A. Schmiechen’s “Reconsidering the Factory, Art-Labor, and the Schools of Design in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” where he optimistically argues that newly mechanized processes ended up generating more demand for art labor, not less. He also suggests that workers created new educational structures—and demanded them from the British government as well—so that they could train for those new opportunities.

It may actually be wishful thinking to claim that Kranzberg’s first law of technology (Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral) is “famous” among people who are not historians of technology. But it should be! Technology is never intrinsically good nor intrinsically evil, but it does tend to amplify existing power structures.

Kranzberg’s law also suggests that different social, economic, and cultural contexts can alter how a technology is used. For more details (and for the other 5 laws, though the first one is really the most quotable), you can read Kranzberg’s 1986 lecture.

This claim (that AI is not particularly good at adapting knowledge from one domain to another) is actually the one I’m least sure about—I don’t have a deep technical understanding of how transfer learning works, and how different the possible tasks and datasets typically are. If you’re more familiar with this, please reach out!

This isn’t a rhetorical question! It’s a serious one. Are artists learning about AI technologies and tactics through various Discords? Specific Twitter accounts? If you’re familiar with this, please let me know in the comments!

A recent post by Evan Armstrong for Every argues that AI images are now indistinguishable from real ones: “Deepfake images are totally believable, easily made by anyone, and cost less than 10 cents to make.”

Armstrong provides some compelling—which is to say, concerning—examples, but he also argues that the problem isn’t the AI-generated content. It’s the way our platforms work for all kinds of content:

[T]he workflow for these AI creators is identical to that of an employee at any other media company: Make something, distribute it through your favorite channels, get paid, and repeat…Because the primary usage of these platforms is distraction and entertainment, truth is secondary.

Thus, the problems of AI-generated content are the same as those of creator-generated content…AI’s only material change is that it makes the images, captions, and videos that make us feel that way cheaper and more convincing. The lies that could be told with Microsoft Word or Adobe Photoshop are just easier to tell with AI tools.

…It may be intellectually easier to blame AI as the problem when the issue resides in people and platforms.

i feel like this is the most careful consideration of this conflict I've read so far. I think the tech can rly help ppl better hone their observing skills and can help ppl get the core structures of like paintings and pictures done more reliably so they can focus on more of the details .

and with writing, being able to simulate the voice of a certain writer to learn more about how they might write something can help people better predict analogous translations in other situations when they dont have the model available. like i made a custom LLM based on Joyce's Finnegan's wake to just simulate more kinds of word puzzles that i can use to figure out interesting ways to take a story that i might have taken a lot longer to think of on my own or would never thought of because of writer's block

My mind is still whirring after this one. Thank you!