falling in love with the short story form

5 incredible short stories about missing continents, mind uploading, motherhood, and love

Whenever I meet a writer, my first question is always: What kind of work do you write? I’m interested in the answer, of course—novels, short stories, poems, essays, blog posts—but I’m also, already, anticipating the next question I’ll ask. Because that’s really the question I care about: Why did you choose that?

Sometimes it’s a choice. Sometimes’s more of a gradual inevitability, as someone tries out different forms and searches for the right fit. “[A]fter a while,” the writer Tobias Wolff once said, we each “have to become reconciled to what it is that our talents and appetites lead us to.” For Wolff, it was the short story:

I’ve always been attracted to the incisiveness, velocity, exactitude, precision of a short story, rather than the long journey of those kinds of novels that we’ve inherited from the 18th and 19th century, with all that great robustness and confidence.

There was a six-month period in 2021 when I was convinced I was a fiction writer. I wanted to write short stories, so I read a lot of them. I’d come across this idea at some point of reading stories the way a carpenter might take apart a chair—disassembling an apparently perfect, whole object in order to figure out its parts, how they were attached, how the object came into being. For short stories, that meant asking: What was the world the story took place in? What details helped me understand it? Who were the characters? How were they introduced to me, and how did they interact with each other? What specific sentences, transitions, descriptions, images made me feel passionately invested in the story?

I still think this is a good strategy for aspiring short story writers, but all it taught me is that I’m not a fiction writer. I don’t feel a deep, clamoring urge to come up with my own stories. But I love telling people about the stories I’ve fallen in love with, and why—where the bright, exuberant feeling of admiration was coming from; what specific things the writer did that felt so masterful. It’s this “mingling of admiration and reason,” as Merve Emre describes it in her latest Yale Review essay, that characterizes the work of a critic.

I wrote about some of my favorite short stories in my latest Atlantic article, “What to Read When You Have Only Half an Hour.” It features 6 favorite short story collections that I would recommend unreservedly—realist and magical realist and sci-fi writers; seemingly minute domestic dramas that touch on greater themes (you thought this story was about motherhood, but it’s actually about nuclear fallout!); stories about physics and math and art and the usual human concerns (love, death, despair, reprieve)…

But there are so many other short stories I love and are not included here! For some, it’s because I’ve only read a few stories by the writer, and didn’t have the context to recommend a whole collection. Other stories are by writers who don’t have a book out yet. So in this post, I’ll recommend 5 stories you can read online:

A short story written like a New Yorker magazine article, about a speculative future where Africa has disappeared

A sci-fi short story, in the form of a Wikipedia entry, about the first human brain to be uploaded to a computer

A short story about the lingering memories of a love affair years earlier

A strikingly experimental short story about being detained at airport immigration and having your diary read (politically and personally distressing!)

A story about motherhood and breadmaking that’s also a delightful satire of art-world language

And if you’re writing short stories of your own—there’s a great Vice interview with Joy Williams on how she writes short stories; and obviously

’s Substack, , is full of craft advice and discussions!Manuel Gonzales’s story about a lost African continent

Manuel Gonzales’s “Farewell, Africa,” published in Guernica in 2013, is set in a world where the continent of Africa has sunken into the ocean. In fact, it’s just one of many continents that have disappeared, and the goal of the Memorial Museum of Continents Lost is to commemorate them. Gonzalez’s story narrates the opening gala for the museum and is structured like a New Yorker article. It reads like typical narrative nonfiction, with a reporter interviewing the museum’s event planner before the gala begins, describing a fictional art installation that goes awry during the party, and interviewing a man who’s been asked to deliver the keynote speech.

The concept behind this story—which isn’t explicitly about climate change and loss but evokes those anxieties in an unexpected way—is already great, but it’s Gonzalez’s tactic of treating it as a fictional journalism piece that makes this story brilliant. Here’s an example of the style:

If you were to ask Owen Mitchell about his speech, his most famous speech, the speech often referred to as the “Farewell, Africa” speech, he would tell you that it was a full fifteen minutes too long…

Mitchell has been known to edit the speech down. Whenever he would come across the speech in a bookstore or when he was at someone’s house and saw that they owned a copy of the speech, which was, for a long time, being reprinted in textbooks and on its own, he would pull it off the shelf and turn to the beginning of the speech and then start to cross out words and sentences…

“The very beginning, those first lines,” he said. “Every time. Those are the worst. No matter what, I always cross out that first part.”

When he told me this, I was surprised and not a little disheartened, for while I am not a huge fan of the Farewell, Africa speech—I find his first inauguration speech and the speech he wrote for Jameson when Jameson first proposed the creation of the office of world governor to be both more eloquent and full of more promise and sturdier judgment than the Farewell, Africa speech—what I liked most about the speech were its beginning lines, which, with their oddly syncopated repetitions, create a verbal space, in my opinion, anyway, of unsettled comfort or discomfiting calm, the only kind of space, in any case, that might prepare the public for the announcement that the African continent was sinking inexorably, inevitably into the sea.

The obvious fictionality of the setting is contrasted by how real this journalistic approach feels—it really does seem as if there’s a reporter talking to a public figure about a real speech. In a 2017 interview, Gonzales explained how he developed this approach:

Usually the story I want to tell helps me frame and structure it. The “Farewell, Africa” story I tried a number of times to tell the story of a guy who wrote a speech about the sinking of the African continent. I tried to write it as a straightforward story, and I kept not being able to find its emotional core, find what I found interesting in the idea in the execution. After a number of failed attempts, I finally thought, Well, what if I tried to write it as a very long “Talk of the Town” kind of piece? Then I was able to create a different narrator for it, a reporter, and then the tone of the “Talk” pieces gave me a lot of freedom when writing the rest of it. The weird, horrifying largeness of the idea kept me stymied when I tried to frame it as a straight story, but trying to frame it in the light, “Talk of the Town” tone, it gave me a lot more freedom in writing it. Sometimes the story that I want to tell begs for a certain kind of treatment.

Stories that use an unusual form (letters, interview transcripts, encyclopedia entries) are some of my favorite works to read. (If you’re interested in novel-length works that fit this description, btw,

has a Substack post recommending 10 of them!)A story about the ethics of uploading someone’s mind

I can’t remember how I came across “Lena”, which wasn’t published in a traditional literary magazine—it appeared in 2021 on the pseudonymous writer Qntm’s website. It uses a familiar format—a Wikipedia entry—to tell the story of the first human brain to be uploaded to a computer. Transhumanists and cybernetic theorists have spent decades thinking about mind uploading. Is it possible? If so, when will we get there? And what ethical issues will we have to face?

“Lena” explores all of this in deliberately neutral, matter-of-fact language. In 2031, the brain of a neurology graduate student named Miguel Acevedo Álvarez is scanned into an “executable image” known as MMAcevado. The story includes details like the file size of the brain (6.75 tebibytes), licensing and IP restrictions for using the brain, and the reception from the scientific community. The Wikipedia-like tone makes some of the emotional and ethical parts of the story even more striking:

[U]nlike the vast majority of emulated humans, the emulated Miguel Acevedo boots with an excited, pleasant demeanour. He is eager to understand how much time has passed since his uploading, what context he is being emulated in, and what task or experiment he is to participate in…

MMAcevedo's demeanour and attitude contrast starkly with those of nearly all other uploads taken of modern adult humans, most of which boot into a state of disorientation which is quickly replaced by terror and extreme panic. Standard procedures for securing the upload's cooperation such as red-washing, blue-washing, and use of the Objective Statement Protocols are unnecessary.

There’s something a little chilling about this description, no? MMAcevado is depicted as compliant and eager to be used, which we tend to appreciate in software and find ethically concerning in conscious beings.

Other parts of the story take ordinary concepts (outdated software, performance benchmarking) and apply them in evocative ways to this fictional world:

MMAcevedo is considered well-suited for open-ended, high-intelligence, subjective-completion workloads such as deep analysis (of businesses, finances, systems, media and abstract data), criticism and report generation. However, even for these tasks, its performance has dropped measurably since the early 2060s and is now considered subpar compared to more recent uploads. This is primarily attributed to MMAcevedo's lack of understanding of the technological, social and political changes which have occurred in modern society since its creation in 2031. This phenomenon has also been observed in other uploads created after MMAcevedo, and is now referred to as context drift.

The world of the story is also conveyed through the Wikipedia-like interface around it. At the bottom of the story are fictional “See also” links to different encyclopedia entries: “Free will,” “Legality of workloading by country,” “Right to deletion,” “Soul.”

The use of the word soul here reminds me of something Meghan O’Gieblyn has observed about transhumanist ideas and spirituality. From her book God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning—

[A]s I became more and more immersed in transhumanist ideas, I increasingly came to experience something like déjà vu. I had initially been attracted to the philosophy because it promised the one thing I longed for—a future. And yet, as I became more enmeshed in the actual details of these ideas, I found myself in a state of regress, returning obsessively to the questions that had preoccupied me as a student of theology: What is soul’s relationship to the body? Will the Resurrection revive the entire human form, or just the spirit? Will we have our memories and our sense of self even in the afterlife?

“Lena” might be one of the best fictional explorations of these questions that I’ve read.

A story from Alice Munro, “the English language’s Chekhov”

When Alice Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 2013, the critic James Wood declared:

Few contemporary writers are more admired [than Munro], and with good reason. Everyone gets called “our Chekhov.” All you have to do nowadays is write a few half-decent stories and you are “our Chekhov.” But Alice Munro really is our Chekhov—which is to say, the English language’s Chekhov.

Munro died on May 13, earlier this year. A friend and Munro devotee, upon hearing that I’d never read any of her works, insisted that I pick up her book Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage—an brilliantly evocative title for a brilliantly evocative collection of stories. But everyone else was trying to read Munro at the time, and library copies were hard to get, so I began with “What is Remembered,” available on the New Yorker’s website.

The story begins with Meriel, a young, married woman attending the funeral of her husband’s best friend. She ends up in a very brief, very discreet romantic entanglement with another man—narrated through very slow, delicate dialogue and hesitant interactions with each other. What’s striking about the story is how Munro narrates the affair in the present tense and through Meriel’s memories, decades later, when she revisits what happened and how it has subtly shaped her life:

The job she had to do, as she saw it, was to remember everything—and, by remember, she meant experience it in her mind, one more time—then store it away forever. This day’s experience set in order, none of it left ragged or lying about, all of it gathered in like treasure and finished with, set aside.

This story is for the Proust fans! The fans of love and loss (okay, no one’s really a fan of loss, but it does lead to the most emotionally saturated and moving literature), remembering and forgetting, restraint and impulse…

Angelo Hernandez-Siaz’s story about immigration, love, and betrayal

I came across

’s writing after hearing him read from a novel-in-progress at Bookforum’s 30th birthday party in NYC (magazines need birthday parties, just like people!). Afterwards, on the subway ride back to my hotel, I read his short story “Customs/Psychological,” published in The Drift’s 10th issue. It’s a special feeling when a story pulls you into such a psychologically acute and intensely realized world, to the point where the phone you’re reading it on and the people shifting around you all disappear from your consciousness—and all that remains is the story. I missed my stop while reading. It’s one of the best short stories I’ve come across this year.“Customs/Psychological” is a story about a young student, Julio Peña, returning to the US after a winter fellowship program in Cape Town, South Africa. At the airport, he’s held up at immigration and passport control and ends up detained in a strange room, then searched and interrogated in even stranger ways.

Part of the surreal quality of the story comes from Hernandez-Siaz’s writing style, where dialogue and narration are compressed together into large, elaborately articulated paragraphs, the speech delineated by em dashes:

— Looks like we’re going to have to do this the old fashioned way, said the agent, abandoning the scanner and gloving herself, empty your pockets and set your bags here, and while the guard busied himself with the scanner the agent tapped twice with the latexed palms of her hands on the wide flat surface of the table beside her desk, onto which Julio heaved backpack and suitcase before ridding himself of wallet and phone — That’s your phone? — My smartphone was stolen — Under what circumstances? — Gunpoint — Violence is man recreating himself, said the agent, is there anything I should know about?

I love this style, which feels bold and distinctive—and has the advantage of making the division between exterior action and interior life especially permeable. Which works well for this story, which partly about Julio’s disorienting experience with customs, and partly about his relationship issues: he’s been dating a woman named Deja for several years, but finds himself drawn to a woman he met on the fellowship program.

I also love how the text shifts between different registers:

The ordinary language of a timid young person interacting with unpredictable agents of a looming bureaucracy (“My smartphone was stolen,” says Julio)

Surprisingly formal, academic language (“Violence is man recreating himself, said the agent”; and references elsewhere to Freud and Sontag)

Irreverent, colloquial language, like the last line below:

Q: …Purpose of travel.

A: A conference.

Q: Which?

A: The 2020 Felton Jonson conference, Unmasking Historical Legacies.

Q: This fellowship, is it anything in the realm of, say, nuclear engineering?

A: No. It’s an experiential learning program for students of color in the humanities at partner universities in the U.S. and South Africa. The January program in Cape Town hosts Fellows from both countries.

Q: There must be ethnic baddies by the boatload.

A: Um, yeah, I guess.

I’m loath to say Here’s what I think the meaning of the story is, because—well—you should just read it! And also because I don’t know if reaching for some objective, clearly legible meaning is important to me as a reader; I care much more about subjective interpretation, of how it feels to read it.

But I was struck by the ending, struck by how the story began to feel less about the airport interaction (Julio versus 2 unfair, pointlessly hostile officials) and more about Julio’s sharp guilt and indecision about his love life…to the point where it’s unclear if the narrative is really happening in the world, or in Julio’s own conflicted conscience. But don’t just read what I have to say about it! Read the story!

Rachel Yoder’s story about artmaking and breadbaking

I have a confession to make: I love all of the obnoxious, self-consciously pretentious art-world speak that you see in exhibition press releases and artist statements. It’s a specific language with idiosyncratic conventions, and it’s fun for me to see it earnestly deployed—but even more fun to see it satirized.

That’s part of why I love Rachel Yoder’s “The Loaf,” a short story published in 2021. It begins with a small, unassuming domestic miracle: a mother wakes up to a perfect loaf of bread that has mysteriously appeared in her oven. How does she explain it to her son? Like this:

I told my son that this could, perhaps, become a commentary on the meaning of home itself. What I was perhaps saying with this house made of loaves is that I wish for home not to be a place of protection but, rather, a location of nourishment.

Furthermore, we might name such an installation “House” while at the same time meditating on the fact that the “house” is something the birds eat and, thus, is an object they are using to construct their own feather-and-bone bodies. Could we draw a line connecting the idea of body and the idea of home? Might we be able to say something about the body being everyone’s first and only house?

In fact, I said to my son, I was your first house, my body. I guess we could even look at the loaf as a sort of analog for the female body at its most extreme, something to be devoured, consumed, transformed…

But can I play in it? the boy interrupted, bored by my conceptual tailspin.

This whimsical opening quickly establishes the mother as someone who has high artistic aspirations. “I am interested in large-scale bread objects,” she tells someone shortly after. And the story becomes about how she pursues her artistic practice within the “bread arts,” which involves an art-historical investigation into a feminist history of bread arts…fame and notoriety thanks to a viral Instagram post…and, of course, the inevitable backlash against her when she insists that no one is allowed to eat her work, only view it.

The story is just fun to read—especially since Yoder perfectly balances unbelievable details (about the mother’s house-sized bread loafs) with extremely believable, realistically grounded ones (about local NIMBYs upset that “residential land was being used for unzoned activities,” like a wayward art installation).

Those are all the short stories I have for today—but if you have any personal favorites, please do comment (or email me back!) with your recommendations!

Four recent favorites

How to get through the Ssense sale with your budget intact ✦✧ David Graeber and Brian Eno in conversation ✦✧ Daniela Spector’s photography + embroidery ✦ Keith Khanh Truong’s riso prints + embroidery

Sheila Heti’s advice to STOP SHOPPING ✦

It’s the most dangerous time of year for young men, women, and they/thems who want to dress well and save money…the Ssense sale is on. In an attempt to reassert my budget (and life!) priorities, I’ve been rereading this Sheila Heti essay, “Should Artists Shop or Stop Shopping?” that a critic/writer I really admire (Megan Marz!) sent me.

Heti’s essay is a close look at the artist Sara Cwynar’s work, which involves elaborately detailed photographs and videos composed of things—candles, jewelry boxes, and more. But it’s also about Heti’s own conflicted feelings about the relationship between creating versus consuming—and about her constant, covetous instinct to shop instead of write:

Shopping is a form of creativity. When I am writing well, I feel no need for shopping. The times in my life I have shopped a lot, it is because I have not been writing.

Shopping is selecting. Writing is selecting.

Shopping is choosing the best thing. Writing is choosing the best thing (the best thing to write about, and the best way of writing it).

Shopping is articulating oneself through one’s choices. Writing is articulating oneself through one’s choices—choices made while writing.

If I tell myself I must not shop, I feel a deprivation and a fear. But if I actually do not shop, I feel self-contained and free. If I don’t write, I feel deprivation and deadness.

David Graeber in conversation with…Brian Eno?? ✦

In one of the most unusual crossover episodes I’ve come across—it turns out that, in 2014, the anthropologist David Graeber and musician/producer Brian Eno had an extended conversation about art, debt, educational institutions, and political revolutions. The recording is available on the Artangel website.

David Graeber is an anthropologist and anarchist activist credited with the phrase “We are the 99%” during the Occupy movement, and the writer of several books, including Debt: The First 5,000 Years and Bullshit Jobs (inspired by 2013 essay, “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant”). Brian Eno is that one ambient music guy I keep on writing about—I have his Oblique Strategies deck next to my keyboard, so I’m always thinking about him!

The entire conversation is worth listening to, but I also found this comment on “bullshit jobs” (from the audience Q&A) quite interesting:

Would love to hear any thoughts you might have on how we can create more "non-bullshit jobs".

EnoGive people more time to invent them! Reduce working hours all round and people will start finding ways of filling their 'spare' time—and some of those ways they find will turn out to be of real value to themselves and to other people too. Most people don't want to sit in a sofa all day watching daytime TV: people like doing things that are useful or fun or joyful or exciting—if they're ever given the chance.

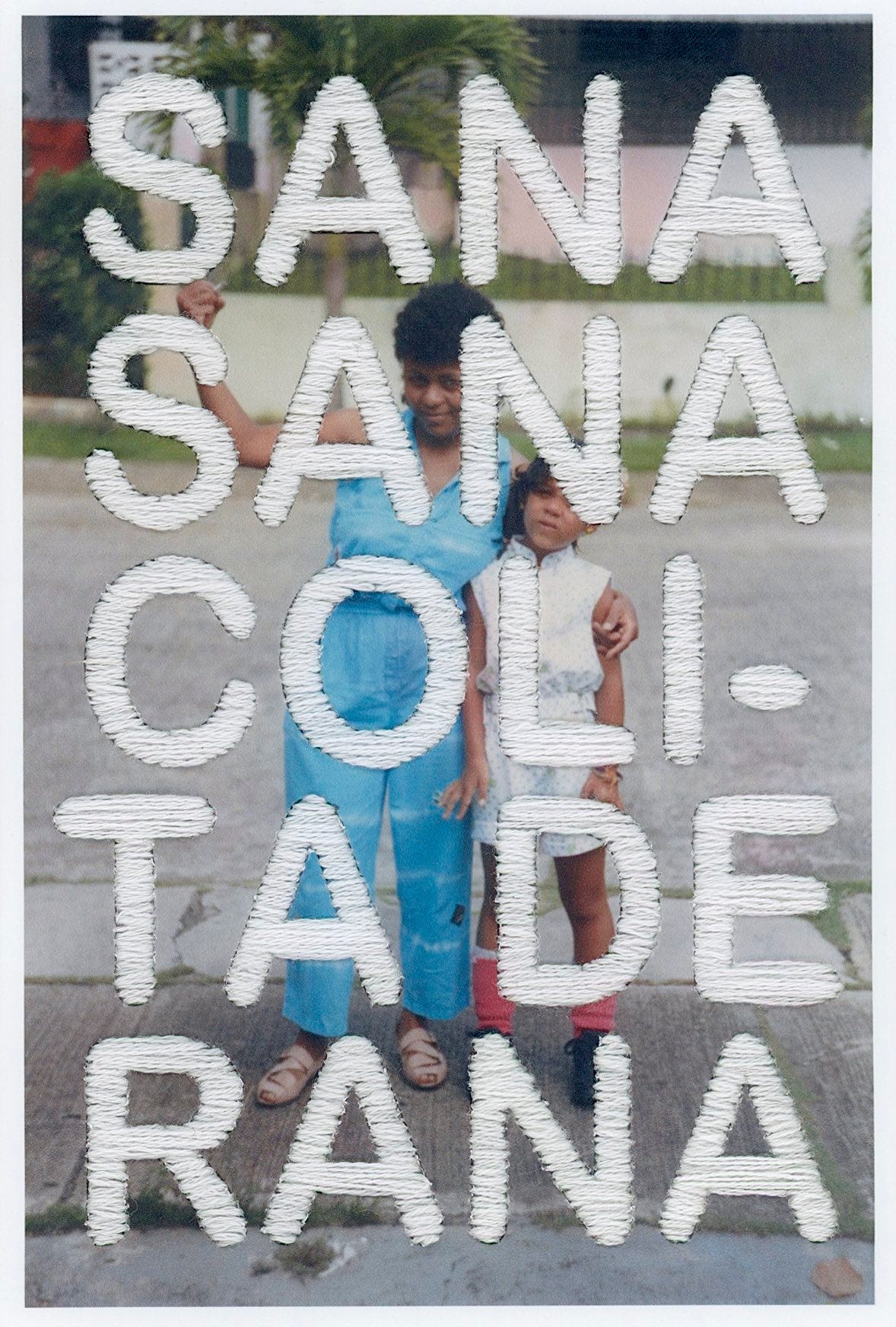

Daniela Spector’s embroidered photographs ✦

On Twitter, the photographer Daniela Spector shared a project where she embroidered family photographs with a phrase from her childhood. I love any mixed-media work—

Keith Khang Truong’s riso-printed “textile” swatches ✦

While we’re on the topic of flat prints + embroidered details…I’m also a huge fan of Keith Khang Truong’s work. Truong was born in Saigon and studied at Tufts, and their work exhibits a fluidity between digital processes and analog materials. For one project, they riso printed a textile pattern onto paper, then adorned it with actual embroidered threads running through:

I love the combo of printed 2D pattern and stitched 3D detail. I bought one of these prints at the Sounds About Riso showcase in NYC last year—one of my most prized possessions!

Once again, thank you for reading these emails! Such a pleasure, as always, to write about great literature, art, design, &c and share it with others. Until next time—

Have you read Alice Munro's short story collection Runaway? Beautiful...

I love that you mentioned Joy Williams. She was the first short story writer whose work I really fell in love with, followed just weeks or months later by Grace Paley. An undergrad professor gave me a copy of Williams's Taking Care. Then, in my first year of grad school, a different professor gave me Jayne Anne Phillips's story collection BLACK TCKETS. The professor was a giant of a man who played football in college and as a roadie for Journey before he started writing his very masculine novels and teaching in an MFA program. Looking back, I loved the incongruity of this, how he selected exactly the right book for me to read, how he knew which voice would speak to me--based on the little he had read of my work.

When I started Fiction Attic Press more than twenty years ago, these were the voices in my head: Williams, Paley, Jayne Anne Phillips, Lars Gustafson (Stories of Happy People). I loved the specificity and--how to say it, exquisiteness? --of these stories. The flash of light and life.

All of these writers were shared with me by professors--and to me that was the true value of the MFA. Not workshops, certainly. The best education was simply being led to these books that I didn't know about and wouldn't have known how to find. (commenting here as Fiction Attic... this is the editor of Fiction Attic, @MichelleRichmond )