everything i read in september 2024

Sally Rooney season ✦ books for cinephiles ✦ and the best book you'll read under 100 pages

Every month I sit down and embark on the Sisyphean task of summarizing all the books I’ve read recently. Why? Practice, mostly. When I started writing book reviews, I realized that very basic questions, like “What is this book about?” and “Was it good?”, take quite a lot of skill to answer!

So these monthly posts were supposed to give me more practice—instead of waiting for an editor to commission a review (which might mean writing a book summary every few months or so), I could write 5 or 10 mini-reviews a month and get better, faster. It felt important to write in public, too; alone, I could get lazy and tell myself, Not this month, I’m busy!

That’s why I began writing this newsletter—as a form of public notetaking and writing practice. What I didn’t expect was that, in the process of flinging these posts into a void, I would actually hear from people who were reading these little summaries. This wasn’t meant to be real writing! It was just practice—practice for something else more important and real. “The lesson here,” the artist Joshua Citarella once wrote, “is that we often don't know what the important work is while we’re making it…you may look back a decade from now and realize that the real work was actually what you were putting online.”

What’s the real work, anyway? Is it reading? Or is learning from the reading? Is the real work what gets published by a “real” magazine, or is it getting to have that thing called a community—people who are reading and writing and thinking about similar things? I have a “real” review coming out soon, which I’ve revised and edited much more carefully than these posts. But I don’t know if I’d be able to finish those larger projects without the small, steady sociability of writing on Substack and hearing from people.

Reading is, often, a solitary pursuit. Which is why I (and people like you, apparently) race to the internet as soon as we’ve finished a book…to discuss! To debate! To discourse!

Anyways, for today’s discursive entertainment, I’ll offer up my September reading: 11 books, mostly novels…but also an incredible Helen DeWitt novella and a nonfiction book about cybernetics and complex systems. Oh, and a film that will break your heart. (Especially if you’re gay.)

Novels

Sally Rooney season

I read Sally Rooney’s latest novel, Intermezzo—as well as Beautiful World, Where Are You, which came out in 2021 but I’d somehow never gotten around to reading. Intermezzo is about two brothers grieving the death of their father, struggling towards a closer relationship with each other, and also figuring out their romantic lives. The oldest brother is torn between his ex-girlfriend and a younger woman who is, basically, his sugar baby? The youngest brother is trying to restart his chess career while wooing an older woman who works for an Irish arts council in a rural town.

Intellectually and formally, Intermezzo feels like the most ambitious of Rooney’s novels, but Beautiful World—which features two women writing emails to each other and reflecting on art, capitalism, fame and love; while entangled, of course, in unnecessarily complex love affairs!—is more romantic, I think. I also have a soft spot for an epistolary novel. More people should be writing letters to each other! Fictional people, but also real people…

But I’ll save my full Sally Rooney thoughts for a separate post.1 It is so exciting to feel part of something, Sally Rooney Season, where everyone is reading and discussing her books in a spirited, invested fashion. I understand why people get into sports! It’s great to participate in a collective fervor!

However, here are 5 links to other Rooney reviews—with some additional thoughts:

I keep on sending becca rothfeld’s “Normal Novels” (which came out in 2021 but remains relevant!) to my friends, which discusses Rooney’s background as a top-ranked debater and the intense effort she puts into writing highly readable, consumable novels. This effort is contrasted by Rooney’s insistence that all this is natural, all this just happened. Rothfeld also makes the very persuasive argument that, “[i]f Rooney’s books have true precursors, they are not Austen’s tense novels of manners but commercial romances that specialize in a certain sort of fantasy fulfillment.”

It makes perfect sense to me that Andrea Long Chu, normally a prickly and demanding literary critic, wrote a fairly positive review of Intermezzo. For Chu, I really think an author’s politics are paramount, and both Chu and Rooney have been outspoken about the genocide in Gaza. Chu is also someone who believes, quite strongly, that what we want sexually is not always conveniently aligned with our gender politics. Which is very much a key anxiety of Rooney’s novels—all these women who, at the end of the day, are satisfied by fundamentally normative heterosexual relationships. (Mostly: Conversations with Friends features a sweet friends-to-lovers romantic arc between two young women, and Intermezzo has an intriguingly non-monogamous ménage a trois, though it’s my least favorite subplot of the novel.)

Jessi Jezewska Stevens (whose short story collection Ghost Pains is incredible—truly—some of the most exciting short fiction I’ve read this year!) has an excellent newsletter post elaborating on how Rooney incorporates Wittgenstein’s philosophy (specifically on language games). Reading Intermezzo, and reading Stevens’s discussion, almost made me want to “get into” Wittgenstein, even though (as you’ll see from the rest of this post…) I have far too much to read already!

And finally, I loved that BDM’s review of Intermezzo in the Wall Street Journal focuses on the relationship between the 2 brothers, which felt exceptionally moving to me…I didn’t really care for the romantic entanglements in this novel, but the sibling relationship! That I cried over! From McClay’s review:

Siblings: They’re easy to lose. For most of your childhood, should you have a brother or a sister, they’re inescapable; their presence can be oppressive. But then one day you move out on your own and keeping in touch with your siblings turns out to require an act of will. It’s easy to drift apart without ever meaning to, as work and romance take over. A sibling relationship may fade amid adult chaos and lingering resentments, the sibling remaining in memory both more and less than a friend. But if you can hold on, even if you sometimes hate each other, even if the other becomes at times an unbearable reflection of the way your life didn’t go—that’s one more kind of love sustained in this world, and that alone would make it worth trying to do.

McClay has also created a power ranking of the great, good, mediocre, and genuinely bad reviews of Rooney’s new novel. Including:

Henry Oliver’s review of Intermezzo focuses on the younger brother, Ivan (the chess-playing one!) and how Rooney writes about neuroatypicality and what it means to be “normal,” socialize “normally,” and function well in the world. I loved this review because I related the most to Ivan—whose internal narrative is compulsively, almost tragicomically obsessed with systematizing and analyzing the world in charmingly specific ways. Here, for example, is how Ivan watches people set up for an evening chess event:

Ivan is standing, wanting to sit down, but uncertain as to which of the chairs need to be rearranged still, and which of them are in their correct places already. This uncertainty arises because the way in which the men are moving the furniture corresponds to no specific method Ivan has been able to discern…

Standing on his own in the corner, Ivan thinks with no especially intense focus about the most efficient method of organising, say, a random distribution of a given number of tables and chairs into the aforementioned arrangement of a central U-shape, etc. It’s something he has thought about before, while standing in other corners, watching other people move similar furniture around similar indoor spaces: the different approaches you could use, say if you were writing a computer program to maximise process efficiency. The accuracy of these particular men, in relation to the moves recommended by such a program, would be, Ivan thinks, pretty low, like actually very low.

I found these passages quite charming, honestly! And Oliver’s review does a careful close reading of how Ivan’s internal monologue works compared to his older brother Peter’s. Peter, in the novel, is a polished, urbane, erudite barrister who treats his brother as an intellectually incompetent, politically unsophisticated child. (I didn’t like him; can you tell?) One of the most moving events in Intermezzo, to me, is how Peter learns to take Ivan seriously. And I liked how Rooney handled their relationship, and how she complicates the question of who is more capable, more high-functioning, when it comes to interpersonal affairs.

Rooney shows us that you can have a neurodivergent person and a non-neurodivergent person who both struggle with the question of how to interact with other people. And in many ways, Ivan does a much better job of that—the resolution of the plot does not pick between the brothers.

Rooney’s constant challenge to her readers is to ask—but who really is normal? If you are continually looking at the external part of a person, as Ivan’s mother does to him and as he does to his mother, you won’t ever understand them.

Non-Rooney novels that I really wish I could discuss with someone

Part of the pleasure in reading a Sally Rooney novel, I think, is that you’re guaranteed to find someone to discuss the story with! That’s not true, sadly, of 2 other novels I read and enjoyed this month. But if you’ve read either, do let me know!

Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind, about a woman adjuncting in NYC and coping with the minor humiliations of being precariously employed in a declining field…and a miscarriage…and a friendship with a charming and very needy friend. Beautiful, measured, somewhat heavy-handed prose. I really love Smallwood’s literary criticism, so I was curious what her novel would be like! I enjoyed it, but it left me tremendously dispirited—which, interestingly, never happens to me with Smallwood’s book reviews, which take on unhappy topics with an invigorating level of cheer. Some of my favorites: “Never Done: The impossible work of motherhood,” which I thought was beautiful and moving—even though I feel much more charitably about Sheila Heti’s Motherhood than Smallwood does. (Heti and I aren’t mothers though, and Smallwood is; could that be why?) And “A Reviewer’s Life,” for the Yale Review's summer issue, about the economic reality of being a freelance book critic.

Lydia Davis’s The End of the Story. Towards the end of September, I stayed at an Airbnb in upstate New York that had an unusually good selection of books, including Lydia Davis’s one and only novel. I’m a Davis devotee (I’ve read all of her books, except her latest short story collection and essay collection) and The End of the Story had all the usual Davis tropes: a disintegrating love affair, a protagonist laboriously reconstructing what happened, anxieties about the frailty of memory…I do think she is better as a short story writer, but this was still quite fun!

For the cinephiles

I’m finishing up my film bro summer with 2 cinematically-themed books:

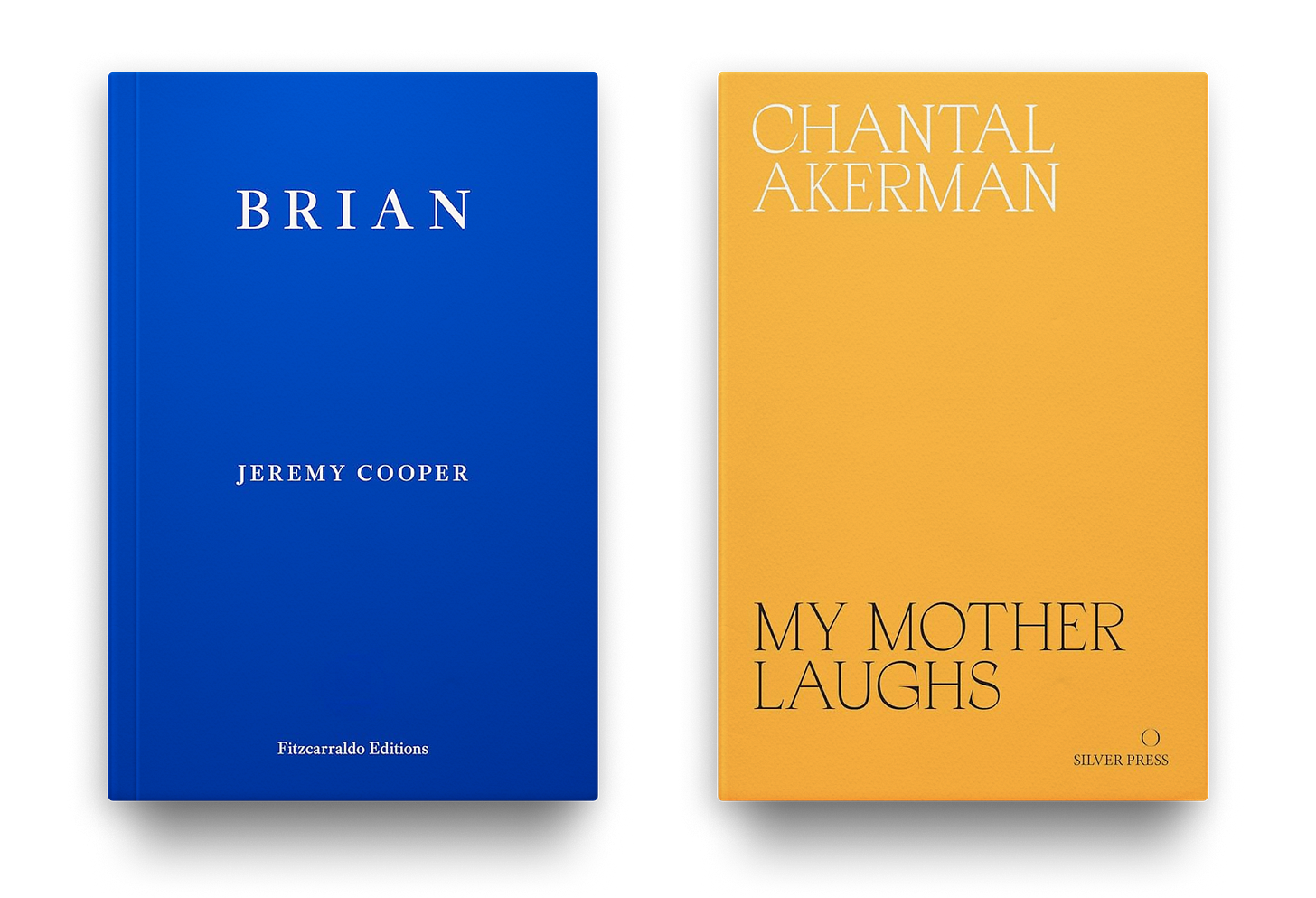

Jeremy Cooper’s novel Brian, which follows a socially stunted cinephile over the course of a few decades. I really did not like it—I might even go so far to say that I resented this book. The main character, Brian, lives and works in Camden, London and lives a quiet, regimented life. He starts becoming a regular at the BFI theater in Southbank, slowly familiarizing himself with the other “buffs” (all men) and developing a taste for directors like Michael Haneke, Yasujirō Ozu, and Chantal Akerman. The book is laden with film references, but doesn’t really describe any of the films in a really visceral, phenomenological way—it’s all facts and details that lie flat on the page. There is a vague gesture at suggesting that, by being so devoted to film, Brian gradually develops leftist political views and a greater capacity to connect with others, but the prose involved feels very clunky and unconvincing. Jeremy Cooper has another book, Ash Before Oak, that’s supposed to be quite good…but reading Brian has made me really hesitant about picking it up!

Thankfully, right after that I read and loved Chantal Akerman’s My Mother Laughs—a memoir-ish book where the renowned film director reflects on her mother’s final days, her filmmaking career, and past love affairs. The text is very diaristic and has a spontaneous, unguarded intimacy to it, and Akerman includes family photographs and stills from her films throughout. I watched Akerman’s masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) earlier this year and found it quite moving—more of my thoughts here!

Commute-sized books

I also began reading the Italian novelist Elsa Morante’s Lies and Sorcery, which I’ve been meaning to read ever since Deborah Eisenberg reviewed it for the NYRB. It’s really good…it’s also 800 pages long!

I tend to get demoralized when reading a very long book, so I’ve been reading a few shorter ones to rest and recuperate:

Yōko Tawada’s Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel (144 very petite pages) is about a man living in Berlin, possibly going mad, and anxious about an upcoming academic conference Paul Celan, the poet and Holocaust survivor. But this description really doesn’t capture what’s fascinating about the book—what propels it forward isn’t the plot, but Tawada’s strange and alluring prose. Here’s an example—you’ll either love it or hate it:

Some time ago he shaved his head. The words that had settled in his hair were too much for him. Tibetan monks shave their heads because their hair is constantly thinking about naked women. Does hair think? Certainly. More than the brain does. It was a spontaneous act: the patient first cut off all the hair he could grab with a pair of office scissors without looking in the mirror…His girlfriend screamed like an emergency brake when she saw him.

"What have you done to your head? I don't want to be with a prisoner from a concentration camp!"

That's when he discovered she wanted to be with his hair, not with him. He took the hair out of the wastepaper basket, put it in an envelope, and mailed it to her with the commentary: "Here's your love back!" One might call this sentence harsh. Her asking what he'd done to his head was harsher still. She knows perfectly well what pain this sentence would cause him.The critic Dustin Illingworth (who I feel very positively about, because he tends to review all of my favorite translated novels) has a review of Tawada’s novel in NLR’s Sidecar blog. Also, if the quote above appeals to you, you must subscribe to Philip Traylen’s newsletter—he is possibly the strangest writer on Substack (non-derogatory) and has a similarly engrossing style!

Helen DeWitt’s The English Understand Wool (73 pages), which is a perfect, gemlike novella that you can eat up in a few hours—it’s Caltrain commute-sized! It’s about young woman named Marguerite, who was brought up in an inconceivably wealthy family—her mother brings her to the Outer Hebrides to shop for wool; to London to get tailor-made clothing; then back home to Marrakech, where her mother has arranged for a conservatory pianist to tutor Marguerite. In between chapters that inspire envy and voyeurism (exactly what is this family doing with their money??) are email exchanges between Marguerite and her editor at an American publishing house. It turns out that, at age 17, Marguerite’s parents disappeared—and the novella quickly shifts into a thrilling and strange heist/mystery story, with some vicious critiques of the publishing industry. Many of DeWitt’s stories are about brilliant, enigmatic, eccentric people besieged by the rampant commercialism and skepticism of the publishing industry, as this Vulture profile from 2016 details. Another common theme is serious intellectual ambition—something reflected in DeWitt’s own life:

DeWitt’s greatest heartbreak had come from the place that had first changed her life: Oxford. After a decade as a student and lecturer with no end to her distinctions and a thesis completed on the concept of propriety in ancient criticism, she had hoped Oxford would give her the sort of freedom…to write an epic work…But Oxford had changed: Thatcherization, credentialization, Americanization, i.e., the pursuit of narrow specialties in the name of job-seeking. She realized she wasn’t interested in writing about writers writing about writers writing about Euripides. She wanted to be Euripides.

Renée Gladman’s My Lesbian Novel (152 pages). I actually made a pact with a few friends to not buy any more books! this month, and then completely forgot about this at Gladman’s reading on Tuesday, which was hosted by Small Press Traffic (a Bay Area poetry organization celebrating their 50th anniversary!) and held at The Lab in the Mission. Gladman has such an obvious gentleness and curiosity—she gave a beautiful reading that made me completely forget about the pact and buy My Lesbian Novel. In it, a Gladman-like narrator speaks to an interlocutor about a novel she wants to write. I just have an endless appetite for these books-about-the-process-of-writing-books, and Gladman has an appealingly conversational style that, every now and then, is interrupted by an intensely beautiful poetic image.

Sometimes I finish a book and feel so completely, irreducibly happy to have read it—and all the images and sounds and characters are still alive in my mind—that it feels as if life can’t get any better than this.

Nonfiction

I spent the second week of September completely obsessed with the ex–investment banker, ex–economist, and now journalist Dan Davies’s The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions. I used to read books like this quite often—comprehensive, lucid explanations of the 2008–9 financial crisis and all the problems with our economy and how we try to regulate financial institutions and emerging technologies. And then I got sick of the entire genre, because so many of those books were bad and dull and it felt like a horrible, unsustainable obligation to read them!

Well, Davies’s book is none of those things—thank god. I felt so thrilled reading it! It’s very impressive when someone can make the history of cybernetics and management theory feel as exciting as a murder mystery, with cliffhangers at the end of every chapter. Which seems to have been Davies’s goal: “I wanted to write a sort of cybernetic political thriller,” he writes, “but it didn’t quite work out that way. It seems that in order to get to the point where the story begins, you need to write eight chapters explaining the construction of the murder weapon. But here we are.”

The book is basically about how systems can become unfathomably complex, and how consequential and terrible outcomes—like financial crises and racially biased decisions—can emerge from them, with no one clearly responsible or accountable. Davies has a particularly original take, which I summarized (but possibly not very accurately…I’m not an economist!) in my Goodreads review:

Essentially, he argues that that liberal democratic governments + large corporations have essentially structured themselves so that…they are not capable of processing information about risks and negative outcomes…

[which] has occurred, Davies argues, because the rise of economics as the discipline for modeling and understanding the world tends to flatten a fairly complex/information-rich world into a simpler one that fits with economic modeling approaches.

That, combined with neoliberalism (Davies makes the very intriguing and unexpected argument that neoliberalism, with its exclusive focus on profits and its assumption that the market contains all the intelligence you need to interpret the world, essentially acts as an information-reducing filter) means that large corporations, central banks, and governments have all become increasingly incapable of handling the complexity of contemporary life and political/economic systems.

This was a really invigorating book, and I suspect Davies’s book will be one of my favorite nonfiction reads for 2024. Speaking of which—I would love to hear your preliminary picks for the best books of 2024! December is coming up! (In, like, 3 months.) Reply to this email or leave a comment…I want to know what book has made you feverishly excited lately!

Essay collections

Just one, but it was really good—perfect, even: Phil Christman’s How to Be Normal. In my brief Goodreads review, I wrote that it “perfectly balances humor, rigorous introspection, lightheartedness, sincerity, pop-cultural fluency, and deep intellectual commitments.” Christman takes on topics that are simultaneously very core to contemporary life and tremendously cliché—masculinity, whiteness, middlebrow culture, bad movies, and Mark Fisher—and writes about them with such clarity and energy!

The “How to be Cultured” essays, for example—it is so easy to write about the desire to be “cultured” and “intellectual” and “informed” in a really tired way, but Christman writes about it in a very fresh and deeply considered way! And “How to Be Married”—so beautiful, beautiful because it makes marriage feel unfamiliar and exciting and imposing. “The reason to get married,” Christman writes,

is because you have met a person interesting enough that, death being inevitable, you’d prefer to experience it with them…

Marrying…was the best choice I’d ever make and that was part of the problem. A good marriage is a eucatastrophe: it ends a phase of your life well but decisively. Things are not the same.

There’s a lot I’d like to quote from this essay collection—here’s something I posted to Substack Notes a few weeks ago:

But yes, read this! I also think the essay “How to Be a Man” is a really fresh and good take on masculinity in the 2020s—but I’m not a man, so I’m not sure if I’m qualified to say? I just like reading about them.

Films

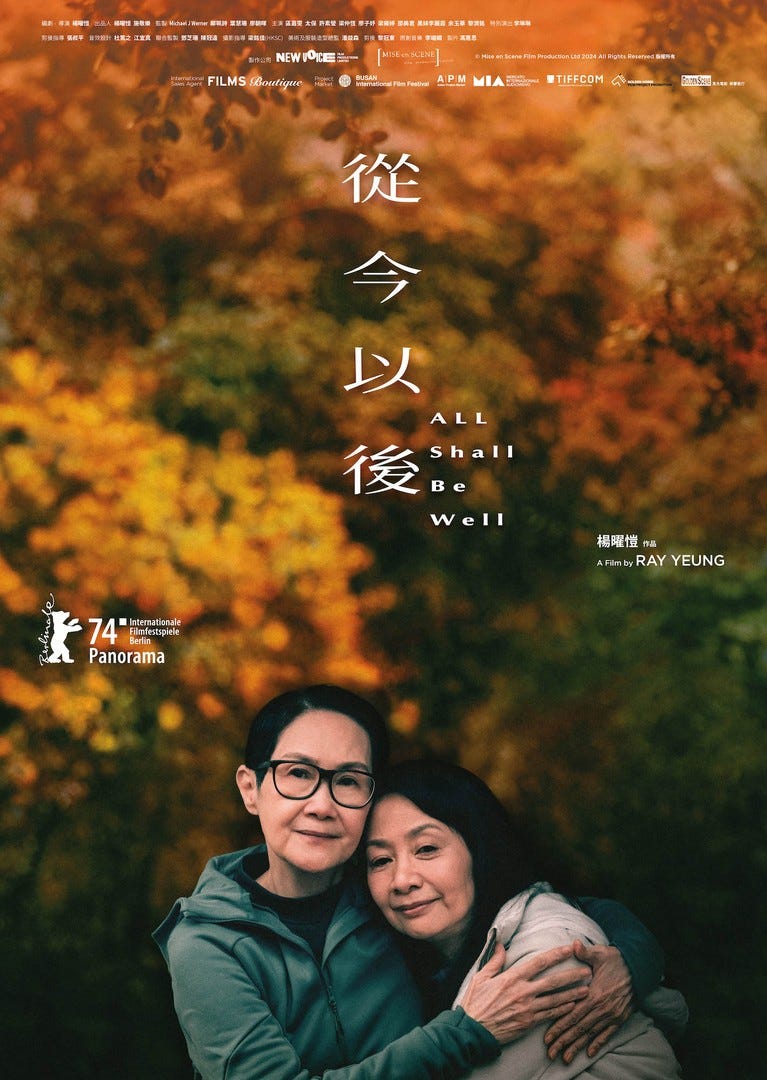

Just one—Ray Yeung’s All Shall Be Well (2024), about an elderly lesbian couple, Pat and Angie, in Hong Kong. The first part of the film feels like a charming slice-of-life narrative about Pat and Angie’s beautiful life together. There’s a very funny scene where Pat (left in the poster above) and Angie (right) are getting ready in front of a mirror. Pat applies moisturizer (I think?) to her face with these firm, vigorous little slaps; Angie, meanwhile, gently presses it into her face in elegant sweeping motions. It’s a cute depiction of a butch/femme dynamic.

The rest of the film, though…is sad! It’s tragic! I cried profusely! It’s not really much of a spoiler to say why—Pat dies unexpectedly, and Angie must cope with her grief and with Pat’s family slowly icing her out of key decisions about Pat’s burial and estate.

The family is portrayed quite sympathetically, though—as financially strained and very hesitant (but ultimately committed to) profiting from Pat’s death, even if it means kicking Angie out of the home they shared together.

While watching All Shall Be Well, I kept on thinking of the New Yorker profile of Edie Windsor—a computer programmer best-known for being the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case that finally gave same-sex couples the right to marry. I can’t even think about this profile without crying! Both the film and the real-life Supreme Court case use questions of property inheritance to open questions about…well, what rights should gay partners have? Legal rights, yes, but also social rights: being recognized as someone’s life partner, being involved in end-of-life and burial decisions…

Now I’m reading the New Yorker profile again and crying in a café in Potrero Hill. Time to wrap up this email!

I’ll forgo the usual list of favorites and share just one recommendation: the poet Zoe Tuck is teaching a workshop, “Reading and Writing through Hoa Nguyen,” through Small Press Traffic. I took one of Zoe’s “philosophy for poets” online classes last year and had a truly lovely time reading Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception with other writers. Zoe is a generous and exceptionally thoughtful teacher—it should be a great experience.

Here’s the course description of the new class, which begins on Sunday, October 27 and meets every other Sunday for 4 sessions:

As a group, the workshop will be reading [Hoa] Nguyen’s work and digging into the Small Press Traffic archive to engage the context in which it first appeared: lit mags and chapbooks of the '90s and early '00s.

Each class will involve discussion of Nguyen’s work and generative writing exercises. These exercises may include drawing details from daily life, the domestic, local ecology, or spirituality, and using techniques like imitation, translation, found language, divinatory tools (I-Ching, tarot), collage, and Oulipian procedures.

Thank you for reading and being part of my “literary” “community”…which, for me, basically means: people who love books and love reading and will share in the heady joys of praising a good book (or trying to understand a disappointing one) with me. I hope October treats you well!

Maybe. I do think that there are so many people writing about Sally Rooney, and so few people writing about the other books in this post…and perhaps it is more useful? interesting? exciting? to spend my energies telling you about a really good book on the history of cybernetics, instead of generating another Sally Rooney take. But we’ll see.

Glad to see that a Substack post can make me feel somewhat like this... "Sometimes I finish a book and feel so completely, irreducibly happy to have read it—and all the images and sounds and characters are still alive in my mind—that it feels as if life can’t get any better than this."

I loved this post so much and have so much that I could respond to.

Like you, after much resistance, I am so glad that I just allowed myself to read Intermezzo (and BWWAY). I was too old for the Harry Potter craze and this was my first time reading alongside everyone else and, like you, I get it.

I have a stack of copies of "The English Understand Wool" at home and it is my go-to gift to give to readers. It is a perfect book.