everything i read in october 2024

the case for reading Flaubert, going to raves, emailing your crush, and losing control

There are many lofty reasons to read—or information, say, or for assistance with the project of self-actualization. But the real reason I read is usually more humble: I need something to do with my time!

It’s conventional, now, to talk about time as something we never have enough of. Between work and school and childcare and social obligations, plus the uneasy feeling that we should be working out more, replying to emails more promptly, and somehow making time for our creative pursuits…it seems like there just isn’t enough time. And certainly not enough time to waste.

But obviously we are also, always, looking for new ways to waste our time. The latest dating-related hot take in The Cut. The newest controversial Bookforum review. The ceaseless quest for new content means that, no matter how little time we have, we’re always looking for more things to do with it.

And sometimes there’s too much time in our hands—too much emptiness, too much uncertainty. I’m in limbo right now—about to begin a new job, about to move overseas, and beset with various bureaucratic delays. All of October, I was thinking of following lines from Mieko Kanai’s novel Mild Vertigo:

She found that she was just as busy as ever without really being able to say what occupied her days, and all that formless time sliced up into sections slipped past before she knew it.1

Formless time unsettles me. It’s why I read: so I can shape time, structure it, and spend it on something meaningful. Which is why I read 10 books in October:

2 novels

6 nonfiction books on techno, mental health, plagues, mortality, modernity and the climate crisis

A collection of poem-shaped things

And a collection of love letter-shaped things

Below, brief reviews of each book—plus some favorite October links!

Books

Novels

I read two novels that are both masterpieces in their own right—one from the 19th century, and one from our own.

The first was Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856), a novel about a beautiful young woman whose longing for love and luxurious objects eventually ruins her life.2 I put off reading Madame Bovary for years, because I assumed (incorrectly!) that it would be tedious, unrelatable, and excessively sanctimonious. It’s not easy to approach a novel that’s often described as a seminal work of literary realism. It’s true—and it also makes Madame Bovary sound dull and virtuous to read, like chewing multivitamins. If only someone had told me that it was full of love affairs and misguided situationships!

And perhaps I would have read Flaubert’s masterpiece a lot sooner if someone had said to me: This is a novel about a young woman who reads too many romance novels, becomes attached to certain fantasies because of them, and never manages to escape her delusions. Because we all have certain fantasies about love—inherited from TV shows, novels, parents, friends—that are harming us, in ways we may not fully understand.

To live with dignity, I think, requires a commitment to actually perceiving reality as it is, and not as you want it to be. I have a certain distaste for trying to extract lessons from novels—a novel is not a self-help book!—but the lessons from Madame Bovary might be:

Don’t delude yourself

Budget carefully

Easier said than done, whether you’re a 19th century fictional character or a 21st century office worker.

The other masterpiece I read is Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai (2000), about a young American woman named Sibylla who moves to London, has a one-night stand with a mediocre writer, and becomes pregnant. To insulate her son, Ludo, from an intellectually disappointing father, she decides to raise him alone. Well, mostly alone. She also has him watch Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 film, Seven Samurai, so Ludo can be exposed to positive male role models.

Ludo grows up to be something of a child prodigy. At the age of 11, he’s learned “five major trade languages and eight nomadic languages,” including Greek, Japanese, Norse, and Swahili. (And he’s mathematically gifted as well.) I tend to dislike stories of young geniuses—which usually fetishize an unattainable level of intelligence, and make me feel dispirited about my own, profoundly ordinary mind. But DeWitt’s novel feels more encouraging. Why? It’s partly because the novel isn’t focused on his talents, but rather his longing to figure out who his father is. And it’s also because DeWitt has a very clear agenda: To convince us, the readers, that we can expect more from ourselves and our children.

In the afterword, written in 2016, DeWitt writes:

We don’t…live in a society where libraries have…the sort of collections that might inspire exploration of great literary repertoires outside school. (We don’t generally find even a collection of Oxford Classical Texts, with relevant lexica and grammars…) We do live in a society where the humanities are increasingly dismissed as impractical, and whatever counts as STEM is A Good Thing because practical. But we don’t live in a society where every schoolchild has Korner’s The Pleasures of Counting, or Steiner’s The Chemistry Maths Book, where every library has a copy of Lang’s Astrophysical Formulae…So Ludo looks impressive not only to [other characters]…but to rather a lot of reviewers. Perhaps he should, perhaps he shouldn’t; perhaps we should really be more interested in the unknown capabilities of the reader.

Reading The Last Samurai is an invigorating experience. It’s so charming—so genuinely touching and adorable and funny! And there’s something quite exciting about the expectations that DeWitt has for her characters and readers. She thinks we can be better than we are. We can learn new languages; we can deepen our knowledge of mathematics. Why not try?

Memoirs & essays

There’s so much I want to say about Emily Witt’s Health and Safety: A Breakdown, a memoir that beautifully combines the personal (a relationship falling apart) and the social (America’s struggles with race, school shootings and COVID). Witt is an investigative journalist and writer for the New Yorker, and her memoir begins by explaining how her interest in psychedelics led her to the NYC techno community.

This aspect of the book has received a lot of attention, but some of the coverage—like this article in the NYT—had the unfortunate effect of making Health and Safety sound like a scene-y party reporter’s book. A lot of my techno friends were very skeptical of the book! But if you’re interested in dance music, it’s a beautifully written and psychologically introspective account of why people get drawn into techno and raves—and the social and political complications that result. Witt also discusses her experiences reporting on the Parkland school shooting and the Black Lives Matter protests in Minneapolis, and uses this context to discuss whether dance music—which, in the US, draws from a long lineage of Black and queer subcultures—can truly be radical.

I loved Witt’s memoir, and I’ve been to some of the nights she describes. The careful, introspective approach she takes helped me think about what techno means to me, and why spaces dedicated to it have felt so important in my life.

I also read 2 essay collections that are, essentially, elaborations of LRB articles:

Adam Phillips’s On Giving Up, named after his remarkable LRB essay of the same name. Discusses “giving up” in a negative context (suicidality, deferring or destroying one’s dreams) and a positive context (giving up on one’s delusions, in order to live more fully). Includes a profound and very insightful interpretation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Jacqueline Rose’s The Plague, which elaborates on her essay “Pointing the Finger.” The essay was published in the first few months of COVID, and discusses how the pandemic revealed political and social inequities. Has an extensive discussion of Albert Camus’s novel The Plague.

If you’re interested in psychoanalytically-inclined literary criticism, both collections are worthy but uneven reads. The essays originally written for the LRB are truly phenomenal…but both collections lack a certain coherence!

Poetry & gossip

Earlier this summer, I was asked by The Believer to review a new essay collection by Lucy Ives, the poet, novelist, art critic, and comp lit scholar. (Isn’t it terrible when people seem to be good at every genre of writing?) I was tremendously charmed by Ives’s prose, and it made me want to find some of her poetry—or, more accurately, her liminal, experimental poetry-ish writing.

I ended up buying a copy of Lucy Ives’s The Hermit from Medicine for Nightmares, an excellent bookstore near 24th St. Mission BART in San Francisco. The Hermit is made up of 80 numbered entries, written in a disarming and nearly diaristic tone. The entries are laden with references to literary theory and philosophy, but it’s all very accessible and endearing. Two of my favorites:

15.What if a person will always be a few steps from life, whatever this is, and what if this person will feel dissatisfied, imperfect on account of this distance? What will we say of them? Do they become a character typical of their time? And, if such a person cannot become such a character, what is the use of them?

And this one:

It’s also worth noting that Lucy Ives has a delightfully retro website—which I actually came across on a design blog years ago, when I wasn’t even interested in contemporary literature!

My friend Chandler also lent me his copy of I'm Very into You: Correspondence 1995–1996, which contains emails between Kathy Acker and McKenzie Wark. Acker, who died in 1997, has become something of a cult figure for her transgressive, iconoclastic writing. Wark is a media theorist at the New School in NYC and has written about cyberspace, contemporary art, and raving. In the emails, Acker and Wark flirt obliquely and then explicitly, while exchanging thoughts on Bataille, bisexuality and books. If you’re extremely voyeuristic and have some familiarity with Acker and Wark’s writing, this is a fun (and very quick) read.

Nonfiction

I hate Halloween (more specifically: I hate buying single-occasion outfits), so on October 31 I stayed in and finished Oliver Burkeman’s Meditations for Mortals. Burkeman is an S-tier self-help and productivity book writer, and his gift comes from a deeply-rooted distrust of the whole genre of productivity advice! His previous book, Four Thousand Weeks, argues that most time-management advice is philosophically bankrupt. It’s all about trying to get everything done—instead of accepting that you’ll never check off all your todos, because, well, you’ll die at some point. (Maybe sooner than you think.)

Only by accepting the fundamental finiteness of human existence, Burkeman argues, can we start to make decisions about how to spend our time. It’s a sobering conclusion, but a useful one. Meditations for Mortals elaborates on this theme. It’s less revelatory than Four Thousand Weeks, but still worthwhile. One of my favorite insights comes from Burkeman’s concept of productivity debt, where “we overlay [an] everyday sense of obligation” (towards our colleagues, children and others) with a feeling that we are morally obligated to be productive. It becomes a kind of “existential duty,” Burkeman writes:

the feeling that we need to get things done not only to achieve certain ends, or to meet our basic responsibilities to others, but because it’s a cosmic debt we’ve somehow incurred in exchange for being alive. As the philosopher Byung-Chul Han has written, ‘we produce against the feeling of lack.’ Our frenetic activity is often an effort to shore up a sense of ourselves as minimally acceptable members of society…

The productivity-debt mindset turns success into a kind of punishment: each new accomplishment merely sets a higher standard that you now feel you’ve got to reach next time around, so it becomes even harder to pay off your debt than it was before.

For more self-critical self-help advice, read—

I also read Hartmut Rosa’s The Uncontrollability of the World, which Burkeman references. Rosa is a German political scientist and sociologist, and The Uncontrollability of the World is about our desire to perfectly understand and control the world—and why this project is doomed to fail.

The driving cultural force of that form of life we call “ modern” is the idea, the hope and desire, that we can make the world controllable. Yet it is only in encountering the uncontrollable that we really experience the world. Only then do we feel touched, moved, alive. A world that is fully known, in which everything has been planned and mastered, would be a dead world…Our lives unfold as the interplay between what we can control and that which remains outside our control, yet concerns us in some way. Life happens, as it were, on the borderline.

What’s fundamentally uncontrollable? Trying to sleep. Falling in love. Whether a potential friend or love interest likes us too. Our health. Being moved by a work of art.

The Uncontrollability of the World feels like a better version of a Byung-Chul Han book.3 By this, I mean: short; contains a sweeping theory about What’s Wrong With Modernity (but the diagnosis is profoundly humanistic, not reactionary and revanchist); feels like a “serious” and “intellectual” read, but is easily assimilated into your existing worldview. If you read and liked James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State or Donella Meadows’s Thinking in Systems, this book is very complementary!

Finally, I read John Doerr’s Speed & Scale: A Global Action Plan for Solving Our Climate Crisis Now. What, Doerr asks, would it take to limit global warming to no more than 1.5° C? Doing so would require cutting global emissions in half by 2030, and reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

Doerr’s book is an attempt to map out a path towards that goal. It was interesting to read this—it’s so different from the climate-related books I typically read (such as Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline, a book I recommend unreservedly), which take an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist approach to understanding the climate crisis. Doerr is a venture capitalist, so he’s much more focused on how capitalism can be used to decarbonize the energy grid, shift consumer behaviors around environmentally damaging consumption, and fund nonprofits devoted to conservation. Doerr’s book was invigorating—it’s nice, actually, to have someone say, Here’s what we could do, and clearly and cogently outline some tactical possibilities for facing global warming. I have quite a few reservations about whether effective capital deployment can, actually, fund technological and sociopolitical change, but Speed & Scale is one of the better arguments for it!

Articles

I’ll close by recommending 4 links—on tech, fiction, political change, and nature—that I’ve been texting many of my friends lately:

Tech execs as problematic prophets ✦✧ “I was hired as an assassin” ✦✧ Why do we insist on believing that art and literature can save the world? ✦✧ How precision leads to poetry

On tech execs as problematic prophets ✦

If you’re interested in a sociologically-inflected analysis of Silicon Valley culture, I can’t recommend

’s “The Cult of the Founders” enough! Farrell applies Max Weber’s concept of the “routinization of charisma”—which Weber used to analyze the structure of religious institutions, like the Catholic Church and Tibetan Buddhism—to Elon Musk’s leadership of Twitter.Musk is doing such a terrible job as Twitter CEO because he is a cult leader trying to manage a church hierarchy. Relatedly – one of SV’s culture problems right now is that it has a lot of cult leaders who hate the dull routinization of everyday life, and desperately want to return to the age of charisma.

As they grow, organizations founded by divinely charismatic leaders must shift to a bureaucratic mode in order to grow and survive. “Cults,” Farrell writes, “don’t scale.” Farrell’s essay is a nice complement (counterpoint?) to that Paul Graham essay on founder mode versus manager mode that made the rounds a few months ago…and the core anxiety that startups face as they scale up.

“I was hired as an assassin” ✦

The world’s funniest English-language writer might be Patricia Lockwood, whose 2021 novel No One Is Talking About This was a pitch-perfect depiction of being terminally online and addicted to Twitter. Lockwood also writes poetry and essays, and one of her greatest hits is the essay “Malfunctioning Sex Robot,” which begins like this:

I was hired as an assassin. You don’t bring in a 37-year-old woman to review John Updike in the year of our Lord 2019 unless you’re hoping to see blood on the ceiling. ‘Absolutely not,’ I said when first approached, because I knew I would try to read everything, and fail, and spend days trying to write an adequate description of his nostrils, and all I would be left with after months of standing tiptoe on the balance beam of objectivity and fair assessment would be a letter to the editor from some guy named Norbert accusing me of cutting off a great man’s dong in print. But then the editors cornered me drunk at a party, and here we are.

One woman, informed of my project, visibly retched over her quail. ‘No, listen,’ I told her, ‘there is something there. People write well about him,’ and I saw the red line of her estimation plunge like the Dow Jones…‘Please tell me you’re writing something about Updike’s 9/11 book,’ another said. ‘Can’t do that,’ I responded, ‘because I’m pretty sure I would die while reading it, and that would be another victim for 9/11.’ Taste and tact had departed hand in hand; I had been reading too much John Hoyer Updike.

In a 1997 review for the New York Observer, the recently kinged David Foster Wallace diagnosed how far Updike had fallen in the esteem of a younger generation. ‘Penis with a thesaurus’ is the phrase that lives on, though it is not the levelling blow it first appears; one feels oddly proud, after all, of a penis that has learned to read.

A good introduction is everything. A good introduction can draw me into an essay about Updike, a writer I have no particular investment in and no real desire to read, simply because I want to know what Lockwood has to say!

I should add that I was reminded of the essay after

posted a note about it. Nussenbaum’s newsletter is also worth a read! His latest post, “Having a Kid Is Already Fucking Me Up and He Hasn't Even Been Born Yet”, has an excellent introduction as well:The most anxiety-inducing part of taking psychedelic drugs—especially those first few times—happens when you’re still sober. Or at least, it did for me. It was always during the anticipation, the hour-ish interregnum while I waited for whatever it was to kick in, that I felt the strangest. I knew I’d just done something that was going to change me—perhaps irrevocably, but at the very least, for the next six to eight hours—but nothing had actually happened yet, and all I could do was sit tight, my head whirling, my stomach an infinite pit, bracing myself for what was coming, even as I knew I didn’t really have any idea what that was.

I didn’t appreciate that feeling at the time, in my rush to become the kind of jaded explorer who had seen it all before. But when it faded away, with age and experience, a part of me started to miss it. It’s easy to be nostalgic for things you didn’t actually enjoy at the time, maybe even easier than it is for less ambiguous pleasures.

Turns out, though, that feeling wasn’t gone forever. Lately I’ve been hit with its echoes, as I count down to the start of a completely different experience.

I suppose the title already gave it away: I’m having a baby. My vocabulary is full of strange new words, the package deliveries have reached letters-down-the-Dursley’s-chimney levels, and my ChatGPT history is stuffed with questions I probably should have asked a doctor. Welcome to my parenting blog.

Why do we insist on believing that art and literature can save the world? ✦

One of the greatest writers and most careful thinkers on Substack is

. I wrote last month about how much I enjoyed Christman’s essay collection, How to Be Normal, which touches on masculinity, the American midwest, and becoming culturally literate.Now I’d like to recommend a brief and excellent newsletter post, “The People Whose Job It Is To Care About Art and Culture Are Always the First to Abandon It,” which contains a very useful discussion of whether literature is actually capable of addressing the problems of the world: genocide, war, conflict, and ordinary human cruelty.

The difference between literature and other things that people do…is that, for some reason, literary people are constantly asking themselves whether they have any right to do their thing in a time of _____. The world will always fill in _____. Your own life will fill in _____ if the world miraculously manages to stay at peace for a minute. Maybe somewhere there is an introspective plumber who asks herself why she merely unclogs toilets in a world where shit overwhelms us. But I doubt that it’s half of what plumbers talk about…and I doubt that it’s something their trade publications regularly run self-doubting articles about. I doubt that plumbing companies spent the summer of 2020 putting out statements about how plumbing practices, as we know them, are rooted in capitalism and colonialism (which they can hardly help being)…questioning whether they themselves should continue to exist, and then vaguely pledging to “be better.” Granted, a plumber is useful in a day-to-day way that a writer usually isn’t — but that’s part of my point. The scale of the things that artists ask themselves to fix, and then get mad at themselves for not fixing, are so great that they could equally serve as an indictment of a given plumber. Or a given anyone.

How precision leads to poetry ✦

My friend Hua and I have been discussing how much ordinary and lovely language is contained in technical descriptions of the world. If you want to write poetic language, you can learn a lot from descriptions that aren’t even trying to be beautiful! They’re simply trying to capture reality, as precisely and clearly as possible.

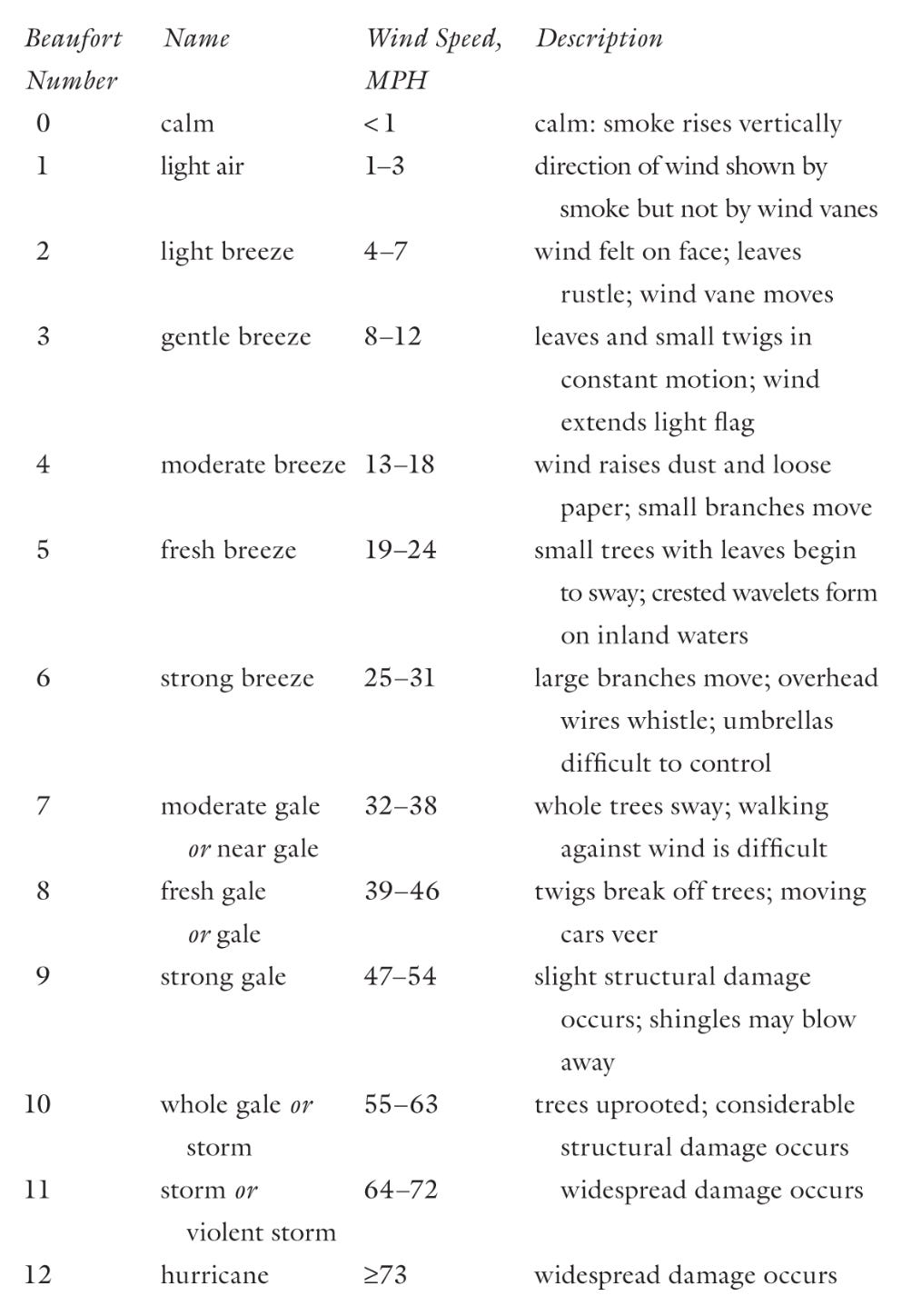

One of the best examples, made popular by the renowned short story writer and translator Lydia Davis, is the Beaufort wind scale:

There is a precision in these descriptions that rises to the level of poetry. Beaufort 2: wind felt on face. Beaufort 5: crested wavelets form on inland waters. Beaufort 8: moving cars veer.

Where else can we find descriptions like these? (Not a rhetorical question! If you have examples, please comment, DM, email back, &c—I’d love to know.) One place I’ve been looking at is this website selling heirloom fruit trees, which has a lovely description of an apple with a distinctive blue sheen to it:

The Blue Pearmain apple tree was first recognized around Boston in early 19th century. Henry David Thoreau sang the variety's praises in his essay, Wild Apples. As the name suggests, the Blue Pearmain apple has a unique bluish bloom over dark purplish skin which makes these apples glow like plums against the tree's foliage. The raised russeting resembles tiny daggers linked with a fine mesh. Crisp, tender, fine-grained flesh with rich and mildly tart flavor. Orchardists describe apples harvested from the Blue Pearmain tree as "heavy in hand" (dense) referring to the noticeably higher specific gravity. The Blue Pearmain apples have also been a longtime favorite for cider.

There’s some incredible language here: apples that glow like plums against the tree’s foliage…I learned that russeting is a word (it refers to the copper-brown, roughened patches on fruits)…the description heavy in hand has a kinetic vitality to it…

For more on the art and technique of description, read—

An image from my life enters your screen

This newsletter is also, covertly, functioning as propaganda that insists on the vitality of the Bay Area’s literary and artistic culture. To that end, here’s a photo of me from an event hosted by Small Press Traffic in early October.

Small Press Traffic is a Bay Area poetry organization and archive (they’re celebrating their 50th anniversary this year!), and they hosted a reading with the poet and novelist Renee Gladman. Readings are so great! You show up, discreetly observe everyone else’s outfits, await compliments on your own, and try to befriend strangers that may or may not become recurring characters in your life.

For more on San Francisco’s history, politics and culture—

Thank you for reading yet another (overlong, overly enthusiastic) newsletter from me! This is the 10th monthly reading roundup I’ve published, and it’s been such a nice way to discuss great books—and, okay, some disappointing books—with other readers and writers. If you’ve read any of these books, I’d love to hear from you!

Mild Vertigo holds a special place in my heart—the first bit of literary criticism I published was a review of Kanai’s novel for the Cleveland Review of Books. Extremely grateful to Philip Harris for editing this piece and for teaching me so much about book reviewing in the process!

It feels strange to try and describe famous novels—when tens of thousands of writers, over the past few centuries, have also described and discussed Madame Bovary. But I’m endlessly interested in how people describe well-known works in their own idiosyncratic ways. If you’d like to share your one-sentence description of the novel, please comment!

Nate Gallant, in a post for

, noted that Byung-Chul Han is “as fashionable as he is prolific.” While the quality of his analyses can be uneven, reading Han is still a pleasure:Personally, I am generally very engaged by the axiomatic grandeur of BCH’s writing. I don't agree with all of it, but I am glad to follow [him]. His examples…are sometimes confusing, and potentially trite…Other moments, however…are very intriguing and productive.

Great quote from Kanai

Introductions - yes! I once wrote an essay about the importance of reading introductions.

Here is my one sentence summary of Madame Bovary: "A cautionary tale about a woman who doesn't know who she is and doesn't spend her time trying to find out."

Celine, Thank you for your reviews and reflections. Food for my literary soul!