everything i read in november 2024

a bad reading month and a good film-watching month ✦ feat. anime classics, Vietnamese & Iranian slow cinema, and Sean Baker's Anora

A confession: I came very close to not finishing any books this month. Halfway through November, I realized I’d started 4 books but finished none of them.1 The problem wasn’t the books. They were beautifully written, intellectually gripping, exciting. This meant I kept on trying to take notes, which was useful but tiring, and whenever I became too fatigued to continue, I would put down my current book and pick up another, and then the same thing would happen again. I began to feel upset: all these great books in the world, brimming over with information and beauty, and I couldn’t finish reading them!

What was the problem? Well, in November I also started a new job and moved cities. But reading, even for pleasure, doesn’t feel optional for me—I suffer when I don’t do it, in the same way that people with fitness routines suffer when they haven’t gone to the gym/swimming pool/yoga studio for some time. Not reading, not working out—these things are excusable when I’m busy, but that doesn’t mean it feels good.

“Exercise,” as

wrote earlier this year, affects “your overall outlook and sense of agency, and that informs everything else. It’s a spiritual endeavor.” He’s writing about physical exercise, but the same is true of intellectual exercise as well. Which is why, in the last 2 weeks of November, I forced myself to do a little bit of both!Below, brief thoughts on:

3 books: Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake; Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others; and

’s novella Money Matters, which is 15k words long (the typical novel, for context, is closer to 90k) and is really what got me back into reading this month!4 films: the anime Perfect Blue, 2 slow cinema films (Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry and Phạm Thiên Ân’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell), and Anora!

and 5 links on the loneliness epidemic, Rachel Cusk, and computational research

Books

Rachel Kushner’s novel Creation Lake ✦

I don’t quite understand why, out of all the novels I could have read this month, I ended up reading Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake. Yes, it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Yes, it’s a new release. Yes, it’s a spy novel set in France that is partly told through emails and partly about a commune of idealistic eco-activists—all things I love.2 But reviews were mixed, which made me—initially, at least—afraid to commit to the 400 page novel.

Some critics loved Creation Lake. Anahid Nersessian’s NYRB review described the novel as “a thriller, a history of the French left, a survey of academic theories about the prehistoric age, and a philosophical novel about human nature. It is also a dazzling work of fiction: brisk, stylish, funny, moving, and, unexpectedly, piercingly moral.” Others hated it: Brandon Taylor’s LRB review called it “a sloppy book whose careless construction and totalising cynicism come to feel downright hostile. As I read, I kept wondering, why did you even write this?”

Ultimately, it was the charged nature of the book—how it seemed to inspire tremendous admiration and antagonism—that made me want to read it. I wanted in on the debate! I wanted to have my own opinion, to figure out where I stood with the novel. I was especially intrigued by how differently people responded to the protagonist, a woman identified only by her alias Sadie Smith.

Sadie was once employed by the FBI to covertly infiltrate left-wing activist groups, but after a job gone wrong—she was accused of entrapment and fired—she’s now a freelancer. When the novel begins, Sadie is in France trying to infiltrate the Moulinards, an eco-activist commune led by Pascal Balmy, a charismatic bourgeois man trying to style himself after Guy Debord, the Marxist theorist and filmmaker. As part of this assignment, she strategically seduces one of Balmy’s childhood friends, so she can show up at the commune as someone safe, vetted, trusted. She also breaks into the email account of Balmy’s mentor, Bruno Lacombe, an elderly French radical who has left anti-capitalist organizing behind. Instead, he lives in a cave (this is actually one of the more believable parts of the novel!) and occasionally emerges to write long emails about Neanderthal art and Polynesian seafaring techniques.

Sadie seems, on the surface, to be a glamorous figure. The glamour is heightened, at least initially, by her cool and unimpeachable cynicism. Once she arrives at the commune, she’s unsparing in her assessment of the gender politics (regressive) and the sincerity of its members:

Whether people cultivate an exterior meant to signal their politics, or they cultivate, instead, a strait-laced appearance that does not signal their politics, their self-presentation is deliberate. It is meant to reinforce who they are (who they consider themselves to be).

People tell themselves, strenuously, that they believe in this or that political position, whether it is to do with wealth distribution or climate policy or the rights of animals. They commit to some plan, whether it is to stop old-growth logging, or protest nuclear power, or block a shipping port in order to bring capitalism, or at least logistics, to its knees. But the deeper motivation for their rhetoric—the values they promote, the lifestyle they have chosen, the look they present—is to shore up their own identity.

It is natural to attempt to reinforce identity, given how fragile people are underneath these identities they present to the world as "themselves." Their stridencies are fragile, while their need to protect their ego, and what forms that ego, is strong.

This observation appears halfway through the novel—about the point when I put Creation Lake down for a week, unable to finish. It was not because of Sadie’s cynicism. It was because Sadie seemed to be all cynicism, purely motivated by craven considerations. Creation Lake gives Sadie a lot of detail, but not a lot of depth. We learn very little about why she’s employed to spy on the Moulinards, and Sadie doesn’t seem to care at all. She reminds us, repeatedly, that all she really cares about the money.

But is that how people work? Everyone wants something more than money. The most interesting novels, even the ones about money and class, are about figuring out what that is. People often don’t want money alone; they want respect, security, admiration, revenge. So there was something mysterious to me about Sadie—I was being asked to believe that she was really just a professional, fundamentally incurious about anything outside of the job description, only interested in getting paid. And I struggle to believe that this is how people work.

There is, actually, one thing she does care about more than money. She begins to care about Bruno Lacombe and his emails. “To enjoy Creation Lake,” Sam Sacks wrote in his review for the WSJ, “it’s necessary to be charmed by Bruno’s erudite email monologues, because this novel, surprisingly, lacks suspense…Kushner presents a realistic depiction of spycraft that consists mostly of waiting around.” Sadie is mostly waiting around, caustically observing the commune, drinking a lot of beer, reminiscing about her career as a covert operative—and we’re waiting around with her. Bruno’s emails are great—and I’m more than a little sympathetic to eco-activists, which helps—but it never became clear to me why Sadie liked Bruno as much as I did. She seemed to be interested in his emails because the novel already included them, and not because there was some intrinsic quality of her character and history and disposition that drew her to them.

Before I began reading the novel, I believed myself to be someone who didn’t need morality or idealism in a novel. I actually hate many novels that are obsessed with moral purity and ethical correctness; I find them sanctimonious and unsatisfying. But Kushner’s Creation Lake poses a problem, because in theory it’s the kind of novel that I would like! It seems to be a novel about the pure and impure motivations behind activism; the ways we try to agitate against environmental disaster, or simply give up trying; it’s also full of interesting and insightful observations. But the lack of ideals—really, of motivations that could be coherently and usefully ascribed to the protagonist—frustrated me.

It’s also very slow reading. “I wanted to write,” Kushner told the Guardian, “an ideas novel that’s not boring, an ideas novel that someone can read and read.” The ideas are certainly there, but the suspense is not. Especially at the end—the climactic scene of the novel feels, essentially, arbitrary; Sadie’s assignment almost gets fucked up, and then it gets resolved through a deus ex machina that comes out of nowhere and is not particularly satisfying to read. And yet I find myself—despite all these negative things I’ve said!—still very intrigued by the novel. Maybe because I want to understand how I could like so much of it and then feel so disillusioned by its nihilism. Maybe because I’ll read interviews with Kushner where she discusses her research, the real-life spy stories she drew on for Sadie’s story, and I feel excited by the project of Creation Lake again. I’ve already read the novel, but in my head I am busy constructing a different novel—a novel where Sadie believes in something, anything.

I will say—if you do read Creation Lake, I’d suggest pairing it with Infinite Light, a Botticelli-inspired ambient album that

(the former editor of Resident Advisor) recommended in a recent post. I finished Kushner’s novel while listening to “Anima Mundana,” which Ryce describes as “Gregorian chant smudged to a Cocteau-like shimmer.”It’s actually perfect for the novel—there is the weight of history, the idealized surface of European art and culture…set against the strange, isolated loneliness that so often shows up in ambient music, which made reading the final scene of Creation Lake, with Sadie gazing up at the stars, feel especially poignant. And I liked how Ryce wrote about the album, too: how it uses

old-fashioned elements—strings and choir-like vocals—to conjure up a sound that feels old, but not quite baroque…it's a bit like watching an AI try to recreate a beautiful 500 year-old painting, occasionally stuttering and glitching on the way. You know that it's artificial, but it's hard not to be bowled over anyway.

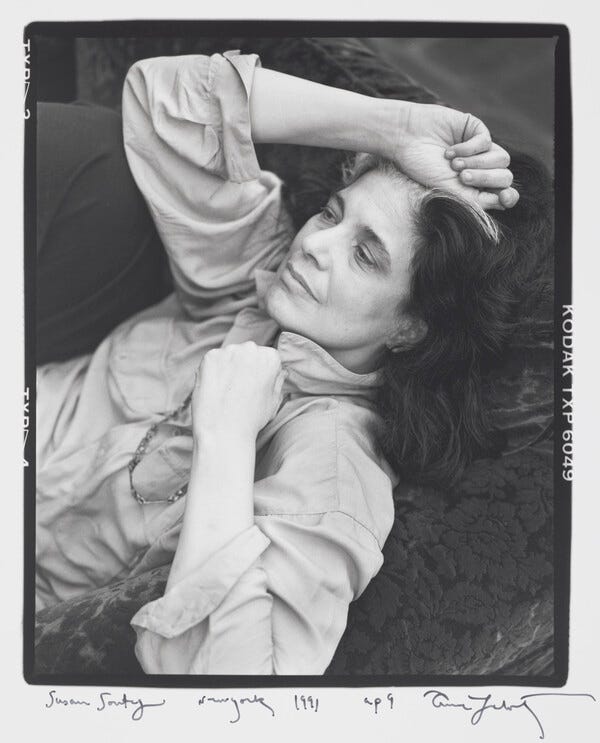

Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others ✦

My understanding of Sontag is incomplete, eccentrically so. Until recently I hadn’t read any of her books, although I did read Deborah Nelson’s Tough Enough (one of my nonfiction picks for the best books I read in 2023), which devotes a whole chapter to Sontag; and I also read Sigrid Nunez’s memoir about living with Susan Sontag sometime this summer.3 And a few years ago, I read a few entries from her published diaries. The extended universe of Susan Sontag is extremely interesting! But I’d started to feel guilty about this—when was I going to read Sontag herself, Sontag the iconic and legendary critic?

Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others is a book-length essay about photography, war and memory. Sontag is preoccupied with how photography tries to capture violence, genocide, suffering—and whether such photographs can have moral force, or if they merely produce a kind of self-satisfied and shallow feeling of horror. “One can feel obliged,” she writes, “to look at photographs that record great cruelties and crimes. One should feel obliged to think about what it means to look at them, about the capacity actually to assimilate what they show.”

Sontag is, broadly speaking, critical of the power of such images—and the ways in which their viewers participate in the pageantry of suffering. “Our sympathy” when encountering such images, she argues, “proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence.” The assumption is that photographs of other people’s pain will activate some useful feeling of care, but they can also distort. Photographs can shape “what catastrophes and crises we pay attention to, what we care about, and ultimately what evaluations are attached to these conflicts.” And “in a world saturated, no, hyper-saturated with images”—the book was published in 2003, and the number of images we’re confronted with has only increased—”those [images] that should matter have a diminishing effect: we become callous. In the end, such images just make us a little less able to feel, to have our conscience pricked.”

Sontag’s essay came out during a time of war—the Iraq War in particular. But we have our own wars now, our own atrocities and genocides. And Sontag’s confrontational approach—with its skepticism of photography, and simultaneous insistence on the ethical importance of what the photographs depict—feels useful and relevant, especially when it comes to photographs of Gaza.

Naomi Kanakia’s Money Matters ✦

One of my favorite articles this year was

’s essay in Dirt, where she discussed how contemporary literary fiction doesn’t talk enough about money. “One of the pleasures of reading 19th-century novels,” she writes,is that authors write openly about money. Take for instance Mr. Bennett, the patriarch in Pride and Prejudice, whose £2,000 a year makes him amongst the wealthier members of the gentry. With that sum, he can comfortably maintain a large household, with a full complement of servants and carriages. On the other hand, he is no Mr. Darcy, who with his £10,000 a year has an immense manor house and accompanying grounds…

But after World War I, writers started to use a kind of code…Money forms a backdrop to [Hemingway’s] The Sun Also Rises, but it's pretty light on the specifics of how much of it each character has…This vagueness becomes an endemic part of Anglophone letters after WWII, as novels develop an intensely interior quality that divorces them from the world of money and manners.

Why are many contemporary novels so coy about money? In the real world, at least, we know—even if we hate to admit it—that money creates constraints on everything. Especially when it comes to love. The cultural obsession with tradwives and hypergamy and marrying up and sugar babies—or, in more polite and veiled contexts, the intense scrutiny applied to the jobs and education listed on someone’s Hinge profile—all testify to how important money is in matters of the heart. Relationships respond to the material conditions of people’s lives, like if one person makes $200k a year and the other person makes $50k. Or if one person is getting $2k a month from their family. Or if one person stands to inherit a great deal, and the other person is—even though no one really wants to admit it—conscious of that fact, aware of it.

It’s very exciting to read someone who’s a critic and a fiction writer, because you can see how their theories of literature map to their actual practice. Which is why I loved ’s Money Matters, a novella published on Substack last month. It’s 15k words long (the typical novel, for context, is closer to 90k) and has an intensely concentrated and very pure consideration of love, money, sex and sincerity.

Money Matters is about a young man named Jack who doesn’t really want to work for money. It helps that his recently deceased gay uncle has left him a house. Jack intentionally became close to his uncle—knowing that the rest of the family had distanced himself, and that the uncle might very well be generous to the one family member still in touch with him. The question for us, as readers, is: Is this selfish of Jack? Exploitative? Or is it simply how people operate when it comes to love and money—where, as Kanakia notes, “the selfish and selfless” are inevitably bound up in each other?

So the novella is about money, and it’s about the games people play when it comes to flirting with, sleeping with, and falling in love with each other. I found the psychological insight in Money Matters very compelling—here, for example, is Jack thinking about two of the women in his life:

The thing he liked about Cynthia was the same thing he liked about Mona, and about himself—they all played the game at a very high level. You could call it 'manipulation' if you wanted, but it wasn't—it was just the game, the only thing that mattered. The game of getting your needs met by other people. Most people played it poorly, haplessly, pathetically—you met them and you more or less immediately knew what they wanted from you, but there was no incentive to give it to them, because they had no ability to intuit your needs and meet them in return. So these losers just wandered around forever, pathetically unloved, ruining relationship after relationship through their own obtuseness.

Of course being able to play the game didn't mean you'd win, because the more skilled you were, the more subtle your needs became…in Jack's case he didn't just want sex, didn't just want fun and excitement and emotional support, he wanted an extra thing too: money.

This makes Money Matters sound nihilistic. It’s not really—I actually find it to be quite fundamentally optimistic, especially when it comes to the capacity of people to love each other despite having the wrong financial incentives for it. But it’s also a novel that realistically engages with how money and class and precarity and security shape our lives!

Films

Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue (1997) ✦✧ Phạm Thiên Ân’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (2023) ✦✧ Sean Baker’s Anora (2024) ✦✧ Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (1997)

An anime about parasocial obsession and stardom ✦

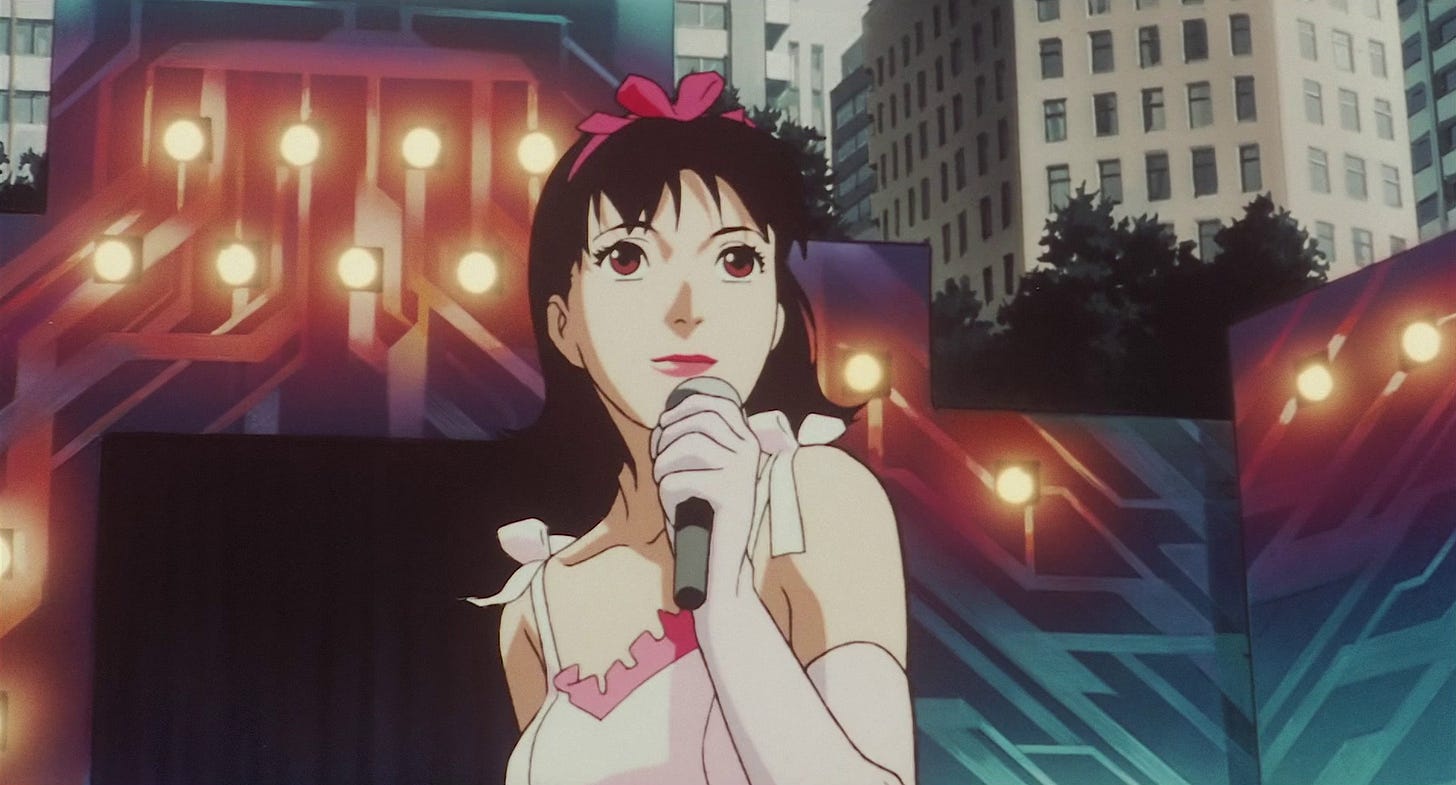

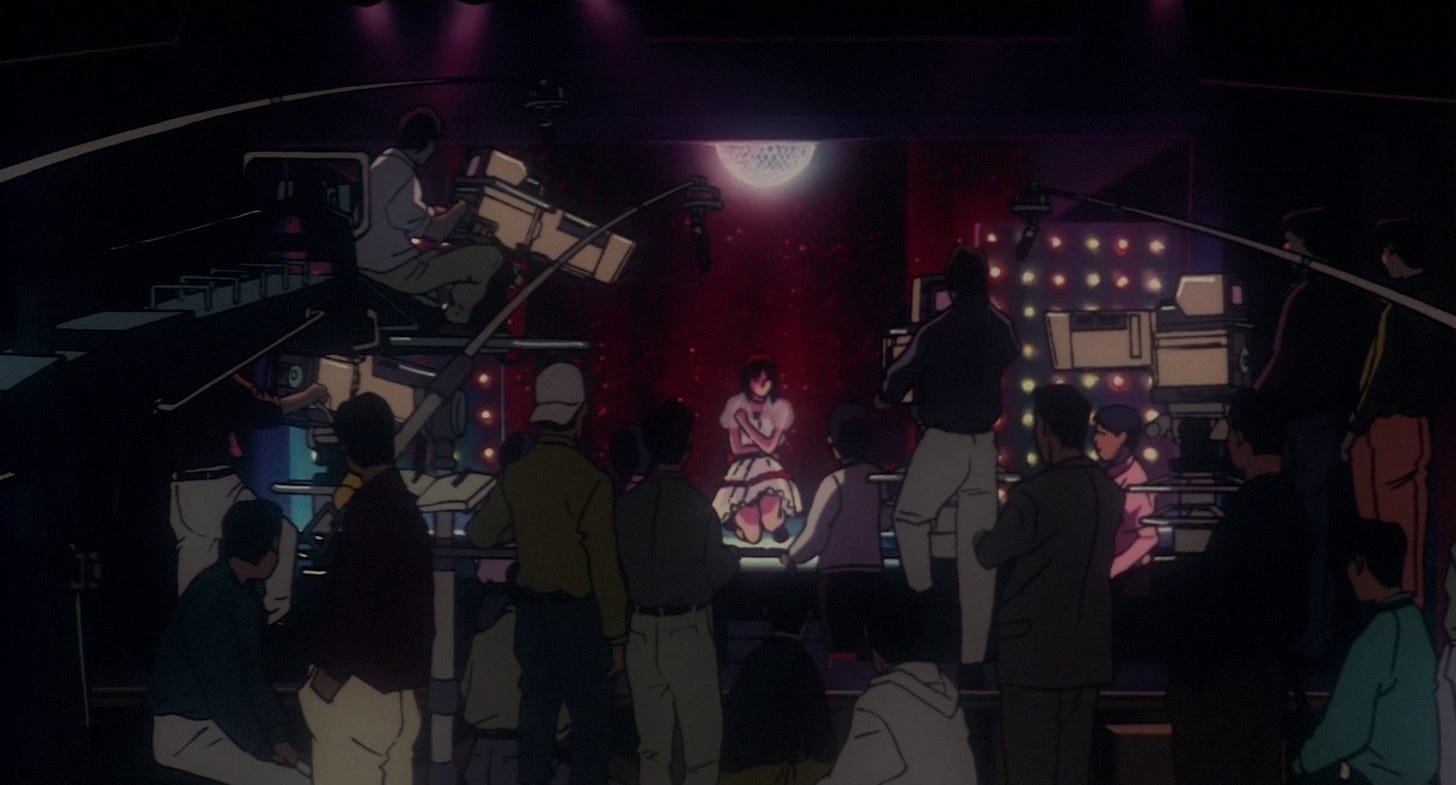

Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue (1997) is arguably one of the canonical anime films (along with Akira and Spirited Away). When I saw it in early November, I was struck by how contemporary it felt! The film is about a young J-pop star, Mima Kirigoe, who leaves her idol group to pursue an acting career. Her parasocially obsessed fans are upset by this, and their disappointment intensifies Mima’s fears that she’s making the wrong decision.

It’s the ‘90s, so at some point Mima buys a computer (I believe it’s an Apple II) and gets her manager Rumi Hidaka, a former pop idol, to teach her how to use it. Soon, she finds a fansite called “Mima’s Room” that is written as if it’s by her, and entries repeatedly emphasize how difficult acting is and how much she wants to return to singing.

The film does an incredible job of portraying Mima’s slow descent into psychosis, as real life, virtual life, and her acting life—she’s filming a TV show called Double Bind, which includes plotlines about mistaken identity and dissociative identity disorder—all blur together. Formally, the film is just brilliant. There are so many cuts that shift you from one scene filled with fearful anticipation, and then land you in a scene that seems to deliver some violent outcome (a closeup of flashing sirens, say) before a zoom-out reveals that the sirens are attached to a children’s toy car.

And on a thematic or content level, Mima’s fear of being surveilled by her fans and treated as inauthentic feels so underrstandable, given that she’s constantly being surveilled as a former pop idol and gossiped about whenever a new episode of her TV show is released! It’s just a great film about celebrity culture and media and parasocial obsession—probably one of the best films I’ve seen this year.4

A very slow, very good Vietnamese film ✦

I also watched Phạm Thiên Ân’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (2023), which won the Caméra d’Or for best debut feature film, at Cannes last year. It’s a 3 hour film about a young man, Thiện, who is now responsible for his 5-year-old nephew after his mother, Thiện’s sister-in-law, dies in a motorcycle accident in Saigon.

The opening scenes shift between the exuberant chaos of Saigon’s streets and the intimate repose of a spa. These are slow, elongated scenes—perfect for admiring Phạm’s extraordinarily precise compositions. For the first 30 minutes, I felt like I’d never seen a more beautiful film.

Then, frankly, I started to feel a little understimulated. Thiện brings his nephew back to the countryside for the sister-in-law’s funeral—this was extremely fascinating to me, since I know so little about Vietnamese Catholic culture!—and then he just sort of…listlessly goes around speaking to people? He speaks to an elderly veteran of the war; he catches up with a long-lost love, who he wanted to marry—sadly, she decided to become a nun instead. Meanwhile, the film inflicts several very long cuts of water dripping on foliage, water dripping off concrete buildings, and people gazing past each other with delicately sad expressions.

I managed to get through the film by:

Practicing my Vietnamese listening skills, which are not very good and therefore appropriately challenged by the range of vocabulary and regional accents in Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell; and

Speaking to my friend (we were watching it at home!) about the beautiful scenes, the composition, the lighting…and then eventually just about our lives. It’s very difficult—strenuous, really—to pay attention to five minutes of an empty mountain road. I’m exaggerating a bit, but still…

By pure coincidence, I was reading an old issue of n+1 a few weeks ago, and was very struck by Moira Weigel’s “Slow Wars,” which is all about internationally acclaimed, art house–y slow cinema films. “Since the turn of the millennium,” Weigel writes,

there have been few if any coherent national film movements. But internationally, a “slow wave” has swept the festival circuit. Many of the features taking prizes at Cannes, Venice, Berlin, and Toronto fit a profile. Their narratives are nondramatic or nonexistent. The scripts are minimal and repetitive, with little dialogue. They unfold in long takes, captured by still or nearly still cameras. Often the figures in the frame stay still themselves.

Who’s included in the slow wave? The Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang; the French director Chantal Akerman (I wrote about her tremendously tedious, tremendously beautiful Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles here); Béla Tarr; the Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami. When slow cinema is praised “as the antidote to Hollywood,” Weigel writes, the praise “draw[s] on such familiar oppositions: contemplation versus distraction, sensuous experience versus technologically driven simulation, grueling authenticity versus facile spectacle… It was not an accident that enthusiasm for slow film took off at the same time as the Slow Food movement. Both discourses praised slowness as a form of resistance to “globalization” or ‘Americanization.’”

American films are meant to be cheap, commercial, fast-paced, empty. Slow cinema films are European, Asian, culturally rich, philosophically relevatory. Weigel questions these binaries—and the assumption that slowness provides more meaning, more significance. And, as my friend

observed in “(in)action movie”:The dominant mode of contemporary cinema might generously be referred to as “contemplative” (or, less respectfully, called out as “boring”)…

Slow cinema feels like the cinephile version of #tradlife nostalgia, for a time when things changed at a less vertiginous pace than they do now. Languid and languorous, it whispers to us: the pace of change is too fast, so slow down, won’t you? But the fleetingness of such respite is made all too clear when the end credits start to roll and the lights in the theater come back on.

I like slow cinema a bit more than John, but point taken! Sometimes we are bored! And there is something about the retreat into slow, pre-technological nostalgia that feels so dissociated from daily life. Sometimes that’s nice. But you can’t really sustain yourself off slow cinema alone.

Anora is the great diasporic film of 2024 ✦

24 hours after watching Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, I watched a completely different film: Sean Baker’s Anora (2024), a fast-paced story of a stripper who gets swept off her feet by the son of a Russian oligarch. There’s a lot of sex, hedonism and complications with his family. Naturally. The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year.

The film deserves basically all the praise it’s gotten—it’s very funny, very sexy, and almost (as I told a friend after) too sharp and entertaining, especially when your senses have been numbed by a 3-hour Vietnamese slow cinema film. It’s also a really lovely portrait of a Russian-American diasporic community in NYC! There’s an early scene where the protagonist Anora, who works at a glamorously competitive strip club, first meets Ivan and he asks if she can speak Russian. She doesn’t speak it much, she says, but she can understand it if he does. That’s really the classic diasporic kid experience, isn’t it?

Anora is excellently written and excellently soundtracked, as we watch Anora’s Cinderella story improbably come together—Ivan is infatuated with her! He even proposes!—and then fall apart. The film really understands why people are drawn to fantasies of marrying up, marrying for money (which also, it must be said, facilitates marrying for love), and finding an escape from the degradations of financial precarity. As Rachel Connolly wrote, “You can see she feels it is too good to be true, that this nice, sweet guy with endless money would sort of arrive out of nowhere and offer her an immediate solution to many people’s biggest problem: How to get enough money to live a good life.”

And the film really understands why these fantasies fall apart when they meet reality, and how painful and hurtful it is for the people who want to believe them. I won’t spoil the film—but it’s very good, and the characters are so wonderfully and movingly acted. “Mikey Madison,” my girlfriend said later, “is a star.” She’s so perfect as this street-smart stripper who is brave and courageous and impetuous and strategic—and, despite all of that, totally out of her league when dealing with Ivan’s family.

I took the bus home from the theater listening to t.A.T.u.’s “All The Things She Said,” which is perfectly and memorably deployed towards the end of Anora:

A film about trying (not to) die ✦

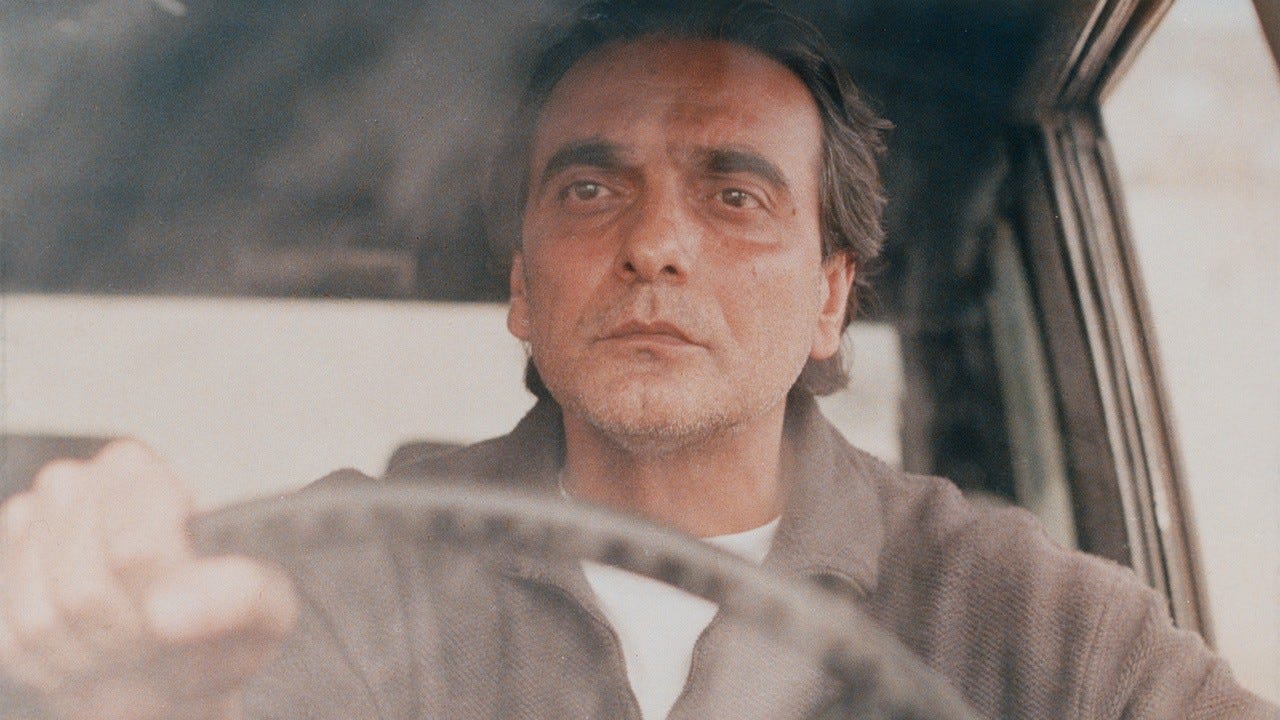

Then it was back to the slow cinema trenches for me: I ended the month with Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (1997). I’ve been meaning to watch a Kiarostami film for a while—ever since I read the critic and essayist Phillip Lopate’s A Year and A Day: An Experiment in Essays, which collects Lopate’s weekly blog posts from 2016. In one post, written after Kiarostami passed away at 76, Lopate wrote that Kiarostami was “not simply the greatest Iranian filmmaker but one of the two or three greatest filmmakers alive (and now I have to amend that last word).”

What a recommendation! And I loved this interview with Kiarostami, where the filmmaker talked about the usefulness and beauty of the moments “where nothing happens”:

The points where nothing happens in a movie, those are the points where something is about to bloom. They are preparations for blooming, similar to a plant which has not emerged from the earth yet, but you know there are roots there and something is happening…So when people tell me “Your movie slows down here a little bit,” I love that! Because if it didn’t slow down, then I couldn’t lift it again.

Kiarostami was part of the Iranian New Wave of filmmakers, which drew from Persian literature and from European art cinema. In Taste of Cherry, we follow Badii, a man driving through Tehran and then the countryside searching for someone to help him commit suicide. Despite this purpose, the film is actually quite funny! We watch Badii cruise around essentially trying to pick up men, who are unsettled by Badii’s overtures and disturbed by his desire to die. Why he wants to die is never really explained, and he insists that it doesn’t matter. All he needs is a little bit of help burying his body.

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem,” the playwright and novelist Albert Camus once wrote, “and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.” And it’s the seriousness of this question that creates such an engrossing tension in Taste of Cherry.

There are some very funny lines, like when Badii tries to convince an Afghan seminarist to help him die: “I know that your duty is to preach and guide people,” Badii says, “But you’re young. You have time. You can do that later.” But in the scenes where we wait—for someone to assist Badii, for Badii to make the final decision (to die or not to die?)—there’s an unbearable empathetic tension.

Essays & articles

I’ll close with a few quick links—on the loneliness epidemic, Rachel Cusk, and some exciting computational research in 2024!

Is the loneliness epidemic real? I loved “The Myth of the Loneliness Epidemic” by the UC Berkeley sociology professor Claude S. Fisher, which takes on the problem of contemporary anomie and assesses whether the social-scientific research supports it. “It is the widely-shared conviction, inscribed in our literature, politics, and folk wisdom, that modern life has degraded intimate relationships.” But many of the studies cited in support of this conviction have clear methodological flaws. What might be contributing to our perception of loneliness, Fisher suggests, are things like a therapeutic culture that encourages intense scrutiny and evaluation of our relationships, coupled with the rise of service journalism and conversations about the purpose of friendship in our lives. We are evaluating our friendships more than ever—and maybe that’s why we often find them wanting. I should also note that I discovered this via The Browser—a wonderful newsletter of that recommends 5 links a day. They also featured my divine discontent post last month!

Literary gossip: Much to say and much to discourse about in

‘s article for Vanity Fair, “Cormac McCarthy’s Secret Muse Breaks Her Silence After Half a Century.” Here is my very brief take: I appreciated Barney’s commitment to telling the story of Augusta Britt, who met Cormac McCarthy when she was 16 years old and estranged from her family, and McCarthy was 42. It is obviously relevant that this is an enormous age gap, but what’s interesting to me is that Britt seems—based on the quotes—to not believe she was romantically or sexually exploited. The more significant thing is that she felt very upset and hurt by how McCarthy used her in his fiction, and I really wish that Barney had dug more into that part—the ethics of how people are mobilized in an artist or writer’s work are very interesting to me, and very challenging!Literary criticism: I loved Elaine Blair’s “Towards a New Realism,” a review of Rachel Cusk’s Parade in the November 21 issue of the NYRB. Cusk is one of our greatest contemporary novelists (in my opinion!) but Parade—a novel about 6 artists who all, in various ways, draw out themes of gender and artmaking and how women are constrained by the world—has been criticized by some, including Andrea Long Chu, for its overt “gender fundamentalism.” Blair’s review is the most subtle and convincing discussion of this that I’ve seen so far; whereas Chu essentially implies that Cusk might be a TERF, Blair is more nuanced. “Cusk uses terms,” she writes, “whose definitions are fiercely contested, words laden with cultural, philosophical, and political freight.” She does this in order to imply that something is “denied and suppressed and darkly continuous in femininity,” but the novel itself does not convincingly explain what that is:

As a novelist, Cusk is of course not obligated to define her terms or proceed by argument…But a highly discursive novel does have to forge some sort of recognizable relationship to the vast flux of discourse on its chosen themes. Parade can neither absorb nor vault clear of…[discussions on] gender, art, domestic labor, and child-raising. Cusk seems to have settled on her own private usage of publicly circulating terms, her own restatements of much-theorized and widely debated propositions, but she has not developed a fictional world to support her idiom.

On computational research: I have a special affection for really, really good scientific writing, and

—a physicist and journalist for New Scientist—has an excellent new article, “Is there a cosmic speed limit on growth?” (first image below) that discusses some new research linking the halting problem (the difficulty of figuring out whether a computer program, once started, will ever stop running) to some fundamental physical limitations on how fast something can grow. I’m not very good at explaining this—that’s why we need writers like Callaghan! But if you, like me, studied computer science in undergrad and miss thinking about computability and complexity, this is a really delightful read.On mathematical quests: Callaghan’s article also led me to another article touching on a classic computer science problem! Earlier this year, Ben Brubaker—also a physicist turned science journalist—published “With Fifth Busy Beaver, Researchers Approach Computation’s Limits,” a deeply compelling article about Busy Beaver, a deceptively simple program that takes a tremendously long time to run. It’s the kind of article that makes mathematical research feel exciting, even epic:

Once upon a time, over 40 years ago, a horde of computer scientists descended on the West German city of Dortmund. They were competing to catch an elusive quarry — only four of its kind had ever been captured. Over 100 competitors dragged in the strangest creatures they could find, but they still fell short. The fifth busy beaver had escaped their clutches.

Of course, that slippery beast and its relatives aren’t actually rodents. They’re simple-looking computer programs that take a surprisingly long time to run. The search for these unusually active programs has connections to some of the most famous open questions in mathematics, and roots in an unsolvable problem as old as computer science itself. That’s precisely what makes the hunt so compelling. Three of the Dortmund participants summed up the prevailing attitude…“Though we know we cannot win the war against the mathematical law, we would like to win a battle.”

Thank you, as always, for reading this newsletter! If you have takes on Creation Lake or any of the films I described above—or, perhaps, if you have an enticing article about computational research to share with me?—please do comment, DM, reply to this email…I’d love to hear from you!

It’s the final month of 2024. Here’s to a peaceful, exciting, meaningful, and satisfactory end to the year. Take care and be well!

It’s fine, obviously, to abandon a book that doesn’t interest you. But what made November especially painful is that the books I couldn’t manage to finish were all very good, possibly even ideal for my interests. I basically read halfway through the following:

Fred Turner’s The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties, as part of a San Francisco–based book club organized by Lucas Gelfond. It’s a really fascinating monograph on how certain American ideals around media and communication were developed during WWII and persisted during the Cold War. There’s quite a lot here about the influence of ex-Bauhaus/Frankfurt School teachers on American education, and the book discusses figures like Margaret Mead, Theodor Adorno, and John Cage in an excitingly new light.

Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels’s Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, which I wrote about in my previous post, don’t deceive yourself.

- ’s The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption, which I fully intend to return to before the year ends! Kelleher has that rare quality I appreciate so much in a writer—a true commitment to beauty and aesthetics, coupled with a self-awareness (but not, importantly, an exhausting self-consciousness) about the perils of caring too much about beauty, to the point where you abandon your ethics and principles in its pursuit.

Elisa Gabbert’s The Word Pretty, a collection of essays that Gabbert previously published in the Paris Review, Catapult and elsewhere. Her writing moves so naturally and effortlessly between personal narrative and literary-critical analysis. It seems effortless, at least—I am starting to suspect that everyone with this style has worked hard on their writing to give the reader such a pristine, smooth experience! Or, as Verlyn Klinkenborg writes in his instructive and helpful Several Short Sentences About Writing, “Flow is something the reader experiences, not the writer.” Anyways, here’s one of the essays from Gabbert’s book:

To me, the epistolary novel is the best kind of novel, which is why I loved Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You—which is also partly told through emails!—so much.

I just realized that I never wrote about Sigrid Nunez’s Sempre Susan—I am perpetually finishing books on the very last day of the month, and those get left out of my Substack posts! But it’s very good; I recommend it unreservedly, for the voyeuristic/those with literary aspirations/both.

Now that we’re approaching the end of 2024, I’ve been trying to formulate what my favorite books, films, &c of 2024 will be. On the list of top films so far, in no particular order:

Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000) and

Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018), which I wrote about back in January

Gary Hustwit’s Eno documentary (2024), which I saw in May! I’ve also written about using Eno’s Oblique Strategies as a creative tarot deck, and how much I loved reading Eno’s diary My Year of Swollen Appendices

Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and

Éric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (1965), both watched and reviewed in June

Akio Jissôji’s This Transient Life (1970), which I saw in July and is one of the most philosophically and ethically intriguing films I’ve seen—also great if you are into Buddhist philosophy!

I'm not sure I'll ever read Creation Lake but I have to stump here for Eleanor Catton's Birnam Wood, which I reviewed (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/03/13/birnam-wood-book-review-eleanor-catton) and which I think is a very good novel about what seem to be similar subjects. So I recommend it! (My review is as un-spoiler-y as possible though not perfectly so.)

Celine, I just read the entire post and I loved your recommendations, but more than that I just loved your writing, your thoughts, your impressions on what you consumed and how you express that through your writing. Just beautifully written, and brilliantly curated. I have not written online in year , and just 3 weeks back I started writing on substack - and writers like you are a huge inspiration to me.