everything i read in june 2024

13 books about art, psychology, gender, and gradient descent ✦ and 3 films about women's labor, family, and love

Lately, I’ve been asking people what their idea of a “summer read,” “beach read,” “vacation read” is. How much, really, do our reading tastes shift by season and location?

I’ve noticed a few tendencies in my own life. I’ll pick out bigger books in the winter (like Mircea Cărtărescu’s 672-page Solenoid, which I read in January last year) . “Classic” novels are also a winter read, because I’m afraid of the commitment involved—even though some of them (like Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina) end up feeling fast-paced and incredibly absorbing. I seem to believe that, in winter, my reluctance to leave the house will make it easier to finish a work.

In contrast, summer is the season of short, swift reads. I want novellas; I want book-length essays; I want anything that can be experienced fully in short, intense bursts. Last June, that meant I was reading Dan Fox’s Pretentiousness: Why It Matters (brief, opinionated, encourages smugness) and McKenzie Wark’s Raving (a short and exciting invitation to go out and dance more with your friends!).

And this June? I read 13 books this month, including:

4 novels by Constance Debré, Sigrid Nunez, and Rachel Cusk (all fairly short!)

3 poetry-ish books, including one collection that uses algorithms (like gradient descent) as inspiration for various poems

2 memoirs about mental health

1 academic monograph

2 self help-ish books about how to schedule your intellectual/creative work

I also watched 3 films (brief reviews below!), made Ottolenghi’s asparagus and gochujang pancakes every weekend (it’s such an amazing recipe for a Sunday brunch at home!)…and scrolled through an enormous quantity of content to pick out 4 favorite articles on architecture, music, food, and…self-sabotage.

Books

Novels

I read the French writer Constance Debré’s Playboy and Love Me Tender, both translated by Holly James and published with Semiotext(e)/Native Agents. Debré grew up in a family described as the “French Kennedys”: one of her grandfathers was the prime minister of France; her father was a journalist and opium addict (a very upper-class addiction, I think!); her mother was a model. Debré married a man, had a son, and worked as defense attorney before jettisoning her polite, bourgeois life—out of boredom, she explains—to come out as a lesbian and write novels.

Playboy, her debut novel, describes her new life and its love affairs, which are variously intense, cool, hesitant, confident, searingly passionate, mercilessly confined to just sex—not love. Buy this book for your lesbian friend who’s a little bit butch (maybe has a motorcycle) and goes around breaking people’s hearts! It’s a very compelling and fast read.

Love Me Tender, the sequel, reveals more about Debré’s old family life—and how, after she separated from Laurent, he weaponized her lesbian relationships to accuse her of being a dangerous influence on their son and prevented her from seeing Paul for nine months: “like a pregnancy,” Debré writes, “but the wrong way around.”

Debré’s style is quite cool and direct, but her pain and misery comes across quite clearly. Early on in the book, she describes how Laurent applied for sole custody, accusing Debré herself of incest and pedophilia. The evidence: Debré introduced her son to a gay friend, and she has books on her shelves by writers like Georges Bataille and Hervé Guibert. The novel chronicles Debré’s real-life fight in the French family courts to see her son, her liaisons with various women, and her bracing anger. Debré’s ability to describe painful things with an unflinching lack of self-pity reminds me of Virginie Despentes’s King Kong Theory, which takes on sexual violence and assault with a similar sharpness.

I also read Sigrid Nunez’s The Vulnerables, after Katy Waldman mentioned it in her New Yorker essay “What Covid Did to Fiction.” At the beginning of lockdown, Waldman notes, it seemed as if it could offer time to write: “the slenderest of silver linings, jumbled up with terror and frustration.” Readers are now reaping the rewards—or suffering the consequences—of literature produced during the pandemic. Waldman offers some enticing similarities between Nunez’s novel and Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence, and it’s this particular description that made me want to read both:

Nunez’s and Erdrich’s novels both express a fear of perseveration, of having too much time to dwell on lost time. They admonish their readers that, if denial is one form of avoidance, allowing your history to prevent you from living what life you have left is another.

Nunez’s novel is about an older woman who, during Covid, ends up housesitting for a wealthy acquaintance in order to care for a parrot. It’s also a very sweet story of intergenerational friendship—partway through the story, a young man moves in after fleeing his disapproving family. The narrator is suspicious of him and upset to be sharing her space. But he’s more open to befriending her: after observing her inability to cook (the narrator eats grilled cheese sandwiches and avocado toast every day), he makes conspicuous offerings of homemade vegan food and edibles. It’s a charming story that reflects back some of the anxieties of the pandemic years (the guilt, uncertainty, and occasional social hostility) without feeling too heavy.

The last novel I read this month was Rachel Cusk’s Parade. The novel shifts between a large cast of characters, including 6 artists—all enigmatically named G—drawn from real-life figures. The first G we’re introduced to is a well-regarded male painter (based on Georg Baselitz) who insists that women can’t paint. As G’s wife reflects:

She wondered whether it was her own indefatigable loyalty to him, her continual presence by his side, that had brought him to this view. Without her, he might still be an artist but he would not really be a man. He would lack a home and children, would lack the conditions for the obliviousness of creating, or rather would quickly be destroyed by that obliviousness. So she thought that what he was really saying was that women could not be artists if men were going to be artists.

Other Gs in the novel include the sculptor Louise Bourgeois (well-known for her uncanny, large sculptures of spiders); the Black painter Norman Lewis; and, at the very end, the filmmaker Éric Rohmer. (He was easy to identify, since I’d recently reread Becca Rothfeld’s essay for Cabinet about the rigorous separation Rohmer kept between his film life and his domestic life as the Mass-attending, married, deeply sober Maurice Schérer.)

In many ways, Parade feels like an interesting synthesis, as Maya Solovej noted in her Baffler review, of 2 of Cusk’s earlier novels. Like Second Place, it’s consumed with the question of how women make art, or are constrained and denied from doing so, as in Cusk’s previous novel Second Place. Like Outline, it’s a novel that resists a single, subjective view of the world—preferring, instead, to venture in and out of multiple people’s life stories.

I found Parade beautifully written and formally so remarkable; but it also, as Andrea Long Chu notes in her review, a book with a very particular view of womanhood, and women’x anxieties. “Cusk,” Chu writes,

is one of those rare writers whose genius exceeds the depth of her own experience. She has taken some fine observations about bourgeois motherhood under late capitalism and annealed them, through sheer intensity of talent, into empty aphorisms about the second sex.

The empty aphorisms are certainly there—like when the painter’s wife, mentioned above, seems to defer entirely to her husband’s genius as a painter, saying: “How had he understood this nameless female unhappiness inside her that made madness such a temptation?” I mean—what nameless female unhappiness is this, that is treated as so universal and yet is so foreign to me? (I prefer to think of my happiness as an ordinary human unhappiness.)

But since Chu published her review, it’s been quite weird to see the usual tweets show up (Well, I won’t be reading Rachel Cusk at all now!) as if Chu’s project is to “cancel” some well-known writer instead of going more deeply into their work and revealing the aesthetic and ideological commitments in them. That project is valuable for Cusk’s fans and detractors.

I loved reading Parade; I also loved Chu’s critique of Parade, since it deepened my experience of the novel; and those sentiments do not—imo—need to conflict with each other at all.

Poetry

I read 3 poetry books in June. The first was The Best American Poetry 2023. Each year’s installment feels very much shaped by the guest editor. For 2023, the editor was Elaine Equi, who I love for her uncomplicated, direct sensitivity (“Ghosts and Fashion” is a lovely example of her style). So I really, really loved this selection of poems. Two of my favorites: Alex Dimitrov’s “The Years” (previously published in the New Yorker) and J. Estanislao Lopez’s poem about wifi, which I posted on Substack Notes a few weeks ago:

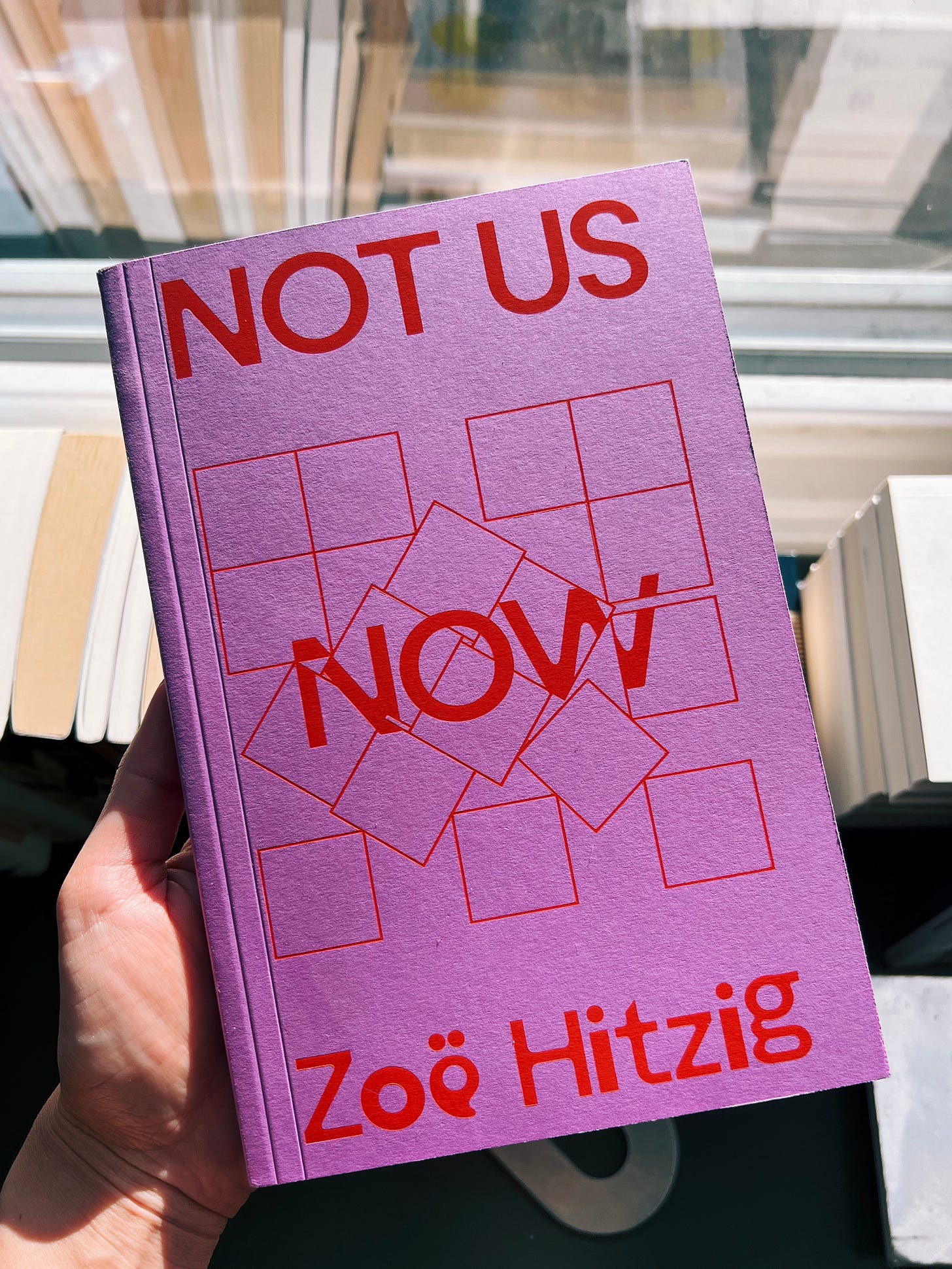

I also bought a copy of the poet and economist Zoë Hitzig’s Not Us Now at her San Francisco book launch last Sunday. The launch featured a very exciting reading experience—the computer scientist, artist, and composer Jaron Lanier would play a brief musical piece on an unusual instrument; then Hitzig would read a poem; then Lanier would play another piece. The

The first part of Not Us Now features several algorithm poems, with titles like “Bounded Regret Algorithm” (previously published in the Yale Review and one of my favorite poems of the collection), “Greedy Algorithm,” and “Zero-Regret Algorithm.” At the reading, Hitzig noted how philosophically and psychologically “weighty” these terms are—what does it mean to describe an algorithm as regretting its past actions? And what does it mean to design an algorithm that avoids regret (something that humans are always trying and failing to do?

And lastly, I read Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet because I am a young person trying to work on my writing, and Rilke is such an encouraging and gentle person for young writers! Even his more didactic advice is full of open curiosity and wisdom:

Don’t write love poems; avoid at first those forms which are too familiar and habitual: they are the hardest, for you need great maturity and strength to produce something of your own in a domain where good and sometimes brilliant examples have been handed down to us in abundance. For this reason, flee general subjects and take refuge in those offered by your own day-to-day life; depict your sadnesses and desires, passing thoughts and faith in some kind of beauty – depict all this with intense, quiet, humble sincerity and make use of whatever you find about you to express yourself, the images from your dreams and the things in your memory.

Rilke also exhorts young writers to not be exhausted by the smallness and ordinariness of their lives: “If your everyday life seems to lack material,” he writes, “do not blame it; blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to summon up its riches, for there is no lack for him who creates and no poor, trivial place.”

Memoirs

I read two memoirs broadly around mental health—by the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner and the American psychologist Marsha M. Linehan.

I highly, highly recommend Marion Milner’s A Life of One’s Own for people who love any of the following: London, keeping a diary, highly introspective writing that draws out something about the broader human condition…

Milner’s memoir came about because she started a seven-year project to keep a diary and understand the nature of her happiness and unhappiness. There’s quite a lot of psychological research on the therapeutic utility of journaling—the social psychologist James Pennebaker is one of the best-known researchers in this area. Some of you may be familiar with his work because it was featured in a Huberman podcast episode last November…but I first heard about Pennebaker through a difficult-to-find but extraordinary book Writing as a Way of Healing by Louise DeSalvo, who taught memoir writing at a CUNY school for many years.

I also read Marsha M. Linehan’s Building a Life Worth Living: A Memoir. Linehan is the creator of dialectical behavioral therapy, one of the earlier Western therapeutic methods to explicitly incorporate Zen Buddhist ideas, and one of the most clinically effective treatments for highly suicidal people and those diagnosed with BPD. I really admire Linehan—she went through incredible mental health struggles in her teenage years and early twenties, and vowed to help others escape the same suffering. Her memoir goes through her personal mental health struggles, as well as her career as a researcher and her attempts to synthesize certain psychotherapeutic approaches (especially the importance of the therapist/client rapport) with behavioral approaches. She also writes quite movingly about how she’s brought together her Catholic faith with the more secular world of science.

Essay collections

I also read Lucy Ives’s An Image of My Name Enters America: Essays. I’m actually procrastinating on my review of Ives’s book by writing this post, so not much to say about it yet! More soon!

Academic monographs

A friend lent me a copy of Jane Ward’s The Tragedy of Heterosexuality ages ago, and this felt like the right month to read it! We’ve been told, Ward writes in the intro, that “heterosexuality makes people happy, while queerness produces difficulty and suffering.” But there’s a strange paradox in straight culture: While straightness is supposed to be natural and default, we’re also told that “men and women naturally find each other difficult to tolerate,” and may even hate each other. What’s up with that? As the online meme goes, Are the straights OK?

Ward is not invested in dunking on straight people; rather, she wants to understand the various narratives that construct such difficult relationships between men and women. Ward focuses specifically on certain genres of heterosexual self-help, including 20th century advertisements for how housewives can keep their husbands happy, and contemporary pickup artists and all the books/courses/workshops on how to seduce women. “Like many personal and relational crises of the twentieth century,” she writes in the chapter on pickup artists, “men's heterosexual misery has been met with a neoliberal intervention —a multilevel industry offering an array of packaged services.” Meanwhile, women often end up as heteropessimists.

Ward’s book is mostly about diagnosing the problem, but the final chapter offers some intriguing suggestions. I mean—it’s a hard problem. I don’t know if there are easy solutions, nor easily synopsized solutions. But Ward suggests that certain aspects of queer culture—the sense that one has in some ways “chosen” one’s attractions and can take pride in them (rather than feeling a sense of shame at being biologically compelled towards them) might be useful for straight people. Not in a straight Pride parade way, but more like…maybe stop treating attraction to the opposite gender as this horrible, detestable thing (because the opposite gender is so cruel, unfeeling, foreign, and other)?

It helps, Ward suggests, to see “heterosexuality as a cultivated desire” that involves some agency, and not merely something one is a victim of. Here’s where I confess that I always find it annoying when straight women say “ugh, I wish I wasn’t attracted to men,” because surely there is something fun and enjoyable about that attraction? The fact that one’s attractions also produce suffering—and that the suffering can be compounded by structural and societal forces—is not a reason, imo, to fully disclaim those attractions and feel ashamed of them. You are who you are; you like who you like.

Anyways, I feel embarrassed that on the last day of Pride month I’ve just written 3 paragraphs about straightness, but maybe here’s a justification—as part of making queerness normal, we also have to abolish this view of the world where straightness is the default, and anything else (being lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, &c) is a special condition.

For more on LGBTQ identity—specifically: using philosophy to think about whether it’s OK to “gatekeep” queer identity—you can also read:

Self-help

I hesitate to call this self-help (which some people understand as a derogatory term)…but I really like books that give me practical, concrete advice on how to live and do the work I care about, and Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Artists Work is excellent in that regard. I’ve been meaning to read Daily Rituals for some time, which reveals how great artists, intellectuals, and scientists like Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Francis Bacon, Franz Kafka, René Descartes, Sergey Rachmanioff, and many others worked. I’m trying to set up a very structured writing schedule this summer, so concrete examples—both people with day jobs (like Franz Kafka) and people blissfully without (like Gustave Flaubert and, later on in her life, Jane Austen)—are incredibly helpful! The usual themes show up: waking up in the morning, having a regular routine… here’s an example from Henry Miller’s life:

As a young novelist, Miller frequently wrote from midnight until dawn—until he realized that he was really a morning person. Living in Paris in the early 1930s, Miller shifted his writing time, working from breakfast to lunch, taking a nap, then writing again through the afternoon and sometimes into the night. As he got older, though, he found that anything after noon was unnecessary and even counterproductive…Two or three hours in the morning were enough for him, although he stressed the importance of keeping regular hours in order to cultivate a daily creative rhythm. “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life,” he said.”

I also read Cal Newport’s Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout. I’m starting to think that Newport’s books circle around the same themes, with slightly different articulations and a new set of reference points. Slow Productivity is good, but it’s not novel; Newport describes a “philosophy for organizing knowledge work” that is less obsessed with the hours you spend at work, and more focused around the “languid intentionality” practiced by great writers like John McPhee or Jane Austen. The principles are: Do fewer things; work at a natural pace, obsess over quality.

It’s basically what he wrote about in Deep Work, updated slightly for the post-Covid world and the Zoom/Slack/Microsoft Teams–induced fatigue that many knowledge workers are experiencing. One problem that Newport acknowledges—and is also, honestly, the biggest flaw in trying to actualize his suggestions—is that many people with office jobs cannot actually set the boundaries needed to follow his principles. How can you do fewer things when your manager assigns you more work than you can do with deep, deliberate focus? How can you work at a natural pace when your company culture is obsessed with speed (and struggles to accept tradeoffs between speed and quality)? Newport offers some suggestions for the humble employee caught between aspirations and reality—I’m curious how well they’d work in practice.

Films

“No more hot girl summers,” I told a friend at the beginning of June. “This is going to be my FILM BRO SUMMER.” Or film girl summer, I guess? Because the first film I watched was the Belgian director Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, her debut film and also—as of 2022—the #1 film in the British Film Institute’s list of the greatest films of all time. (Any such list is, of course, highly contingent on who’s voting. Every decade or so, the BFI invites film critics, curators, archivists, and academics to submit a list of their top 10 films. In 2022, they asked over 1,600 people for their picks.)

Jeanne Dielman is about 3 days in the life of a widowed Belgian housewife as she makes breakfast, shops for groceries, pays her bills, boils potatoes, makes dinner for her teenage son, occasionally performs sex work. It’s 3 hours long and, as my friend Zach noted, is a particularly relentless example of type 2 fun: remarkably boring in the moment, remarkably interesting after you’ve watched it. The intolerable repetitive banality of each day is the point, and it’s reinforced through each action—the potato peeling, the coffee making—occupying a similar amount of time on-screen as it would in real life. There’s a “revelatory tedium” to the film, as Jessica Winter noted. “Akerman rewards the viewer’s attention by recalibrating it” towards the most minute details. The first day in the main character’s life is stable, reassuring, ordinary. On the second day, we begin to notice small slips, creating an “invisible gas of apprehension, then dread.” It’s a remarkable film, and endlessly interesting to discuss—even though, when I was watching, I could hardly bear the boredom.

I also watched the Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story, #4 on the BFI list. It’s a story about an elderly couple that goes to Tokyo to visit 2 of their children—who are politely uninterested in spending time with their parents and occupied with their jobs, children, lives. It’s one of their daughter-in-laws—the wife of their second son, who died during WWII—that ends up taking them around town.

When I watched it with a friend (this newsletter sponsored by all my friends who own large TVs so that I don’t have to!!!), I kept on saying, plaintively: But where is their filial piety? I found myself identifying quite deeply with the elderly couple—who are mild-mannered and understanding, but still feel their children’s lack of care. But positionally speaking, I’m much closer to the adult children. What do we owe our parents? And what kinds of familial norms are retained in a time of cultural dislocation and change? Tokyo Story reveals the stakes of these questions, but it doesn’t commit to a very didactic answer. It’s a lovely film—very lovely, very heartbreaking.

I also watched Trần Anh Hùng’s The Scent of Green Papaya and had decidedly…mixed! feelings on it! Earlier this year, I watched his latest film, The Taste of Things, and was very moved by the attentive focus on cooking and dining—the film opens with the elaborate preparations for a gourmet meal—and the love story between a wealthy man and his employee Eugenie. The Scent of Green Papaya, his debut film, shares those themes—but the cooking is much simpler (not a problem, to be clear), and the love plot as well (this is the problem).

The film is gorgeous—and I appreciated the chance to practice my Vietnamese listening skills, which are extremely poor at the moment!—but it is basically all vibes and questionable plot. However, the film is quite cute in that it stars Trần’s wife, Trần Nữ Yên Khê, who he’s collaborated with for many of his projects—she was the art director for The Taste of Things.

Links

Four final links for you—on architecture, music, food, and self-sabotage. (Admittedly the last category is not like the others…but it is also a core part of the creative/intellectual experience!)

Architecture

I’ve been fascinated and horrified by the slow-moving architectural disaster described in Ian Parker’s “Kanye West Bought an Architectural Treasure—Then Gave It a Violent Remix” for the New Yorker. Briefly: Kanye West (needs no introduction, hopefully) bought a home by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando and proceeded to destroy it.

For fans of Ando—and I count myself among them—there is something gruesomely fascinating about this piece. Ando originally trained to be a boxer before falling in love with architecture, and in true autodidactic fashion, educated himself through informal coursework (night classes, correspondence classes) and visiting buildings by other great architects. He established his own firm in 1968 and has since worked on private residences, art museums, churches, and other projects. Ando has won the Pritzker Prize, among other architectural awards, and is revered by many. “[A]n appreciation for Ando,” Parker writes, “can take the form of veneration”:

For very wealthy people who spend some of their wealth on art, no living architect seems more likely to make them feel that they’re buying not just a fine home but the work of a major modern artist. An Ando house will require expensive and exacting construction; it will have a controlled, sober beauty that photographs well and that plainly communicates contemporary, if not avant-garde, taste. And it will be rare. The client will receive personal validation of the most tangible, bombproof kind. Ando has said that, after being introduced to potential clients, “my decision to accept their projects depends mainly on their personality and aura.” An American real-estate agent who has had some interactions with Ando recently told the Wall Street Journal that “it was like working with God.”

If you’ve visited Naoshima, Japan—known as Japan’s “art island” for the sheer density of contemporary art museums and site-specific works—you’ve probably experienced some of Ando’s work.

Kanye West also visited Naoshima (he’s just like me!), and namechecked Ando in one of his songs (okay, less like me). The truly unrelatable thing is that Kanye West bought an Ando-designed mansion in Malibu, California and then proceeded to hire a handyman to rip out the cabinetry, plumbing, doors, staircases, HVAC, and lighting. After the damage was done, Ye seemed to have a crisis of faith—contacting a more experienced architectural firm to restore the mansion to its former glory, and then contacting the Oppenheim Group (made famous through the TV show “Selling Sunset”) to try to sell the house as-is. As the New Yorker piece notes—with incredible understatement—

[I]t’s hard to do architecture in bursts of enthusiasm and grandiosity. Ye is serious about buildings…and he has unusual reserves of creative insight and energy, as he has at times himself observed. (“I am Warhol…I am Shakespeare in the flesh.”) His urgency can be attractive; as he once said, in a conversation with a design publication, “I don’t want to be dead when the world starts getting good.” When [the Swiss architect] Olgiati worked with him, he praised Ye’s radicalism and called him “probably the most interesting client that an architect can have.” But the path from an idea to a built thing is long, expensive, collaborative, and difficult to reverse…

In a recent conversation, [one] architect, who requested anonymity, told me that some of his senior partners met with Ye…Ye had been “full of visions,” but “the feeling was that there is something about architecture that requires a little bit of contemplation. And, maybe, a little bit of patience.”

Music

Even though I know nothing—like truly! nothing!—about music production, I’ve been enormously inspired by this 2022 interview with Tony Price, the Canadian producer, DJ, and graphic designer.

I’m deeply fascinated by how musicians and producers work. Maybe it’s because that music, like literature, is an art form that exists over time—you can’t glimpse the whole work in a single instant (as you can with visual art), and have to experience it moment-by-moment, through the experience of reading or listening. (I’m always excited to discover new ways to connect 2 disciplines—this one comes from Danielle Drori, who teaches at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research!)

Or maybe it’s because music, like design, is a discipline that is indelibly influenced by new technologies—changes in software and hardware can’t help but make their imprint on how designs look and how music sounds. That’s something Price touches on beautifully in the interview, when he describes how audio that is too “clean” feels artificial to us—even though the signifiers of a rough, authentic sound can be just as artificially constructed:

I am very inspired by, maybe even obsessed with the artificiality of recorded sound. There is nothing “natural” about recorded sound or music. The amount of hiss, crackle and noise, enhanced by layers of compression that accompanies a recording of radio chatter or music from the 80’s or 90’s is aesthetically appealing because as all of these artifacts stack up, it’s as if they are inviting you through a portal into some alien past.

…we’ve hit a point where having a song or recording that sounds too “good” or too “clean” also signals a sense of unwanted artificiality. When it comes to music technology, so much energy and so many resources were spent for decades trying to find a way to “clean up” sound, eliminate hiss, hum, crackle. We went so far into this idea that we started to hate what we were hearing and we’re now at the stage where every other week there is a hot new plugin or piece of gear that purports to replicate old, noisy gear to a tee.

This is what I meant when by talking about some sort of ‘machinic unconscious’, the vast network of sonic artifacts that lie beneath, between, inside, and at the edges of all recorded sounds…In my productions I try to enhance, exploit and exaggerate these qualities…not only because I like how old things sound, but also because I feel that by letting these machines speak, they might tell us something about ourselves that we might not be hearing.

I also loved Price’s perspective on making music that is explicitly nostalgic, explicitly referencing and recalling the past:

[I]t’s become popular to take the stance that a culture engulfed by “retromania”, “hauntology” or “formalized nostalgia” is a regressive one plagued by some sort of artistic impotence that has ruined the world. This is definitely a point of view that I have at times shared but it’s just miserable to look at the world in this way, really. It’s no fun. In reality, if I hear a well-written song on the radio that is an overt pastiche of an 80’s production by Jam & Lewis or Trevor Horn, I’m going to turn it up. Some of the best pop music of the last decade was straight up 80’s aesthetic revivalism. I’d even argue that producers like Sophie…used the sounds of 1980’s production as a launchpad into levels of sonic futurism that were never possible up until that point…

I was raised by Polynesian and Greek parents who were very active club-goers in those cultural circles in Toronto in the 1980s. I’m always going to have an inclination towards the sounds and grooves of freestyle, boogie and house music as that’s what I was raised on. Should I actively try to avoid making music that speaks to my soul because it’s philosophically “bad” to try and replicate the sounds of the past? We have access to so much music and so much software and cheap recording equipment that it is inevitable that we would end up emulating the past. I think we need to stop with the eggheaded negativity and just have a good time!

Yes! Let’s all just have a good time! Although I don’t think negativity is always unwarranted—which brings me to my next link…

Food

On my last visit to London, I was splitting a bottle of wine (several bottles of wine, to be perfectly honest) with 5 other people at my girlfriend’s flat. At some point we began discussing Vittles, which began as a humble London-based newsletter about food and is now, basically, an influential independent magazine that everyone I know seems to subscribe to. (By “everyone,” I mean 4 of the 5 people I was with—but how often can you say that about any Substack?)

Vittles has restaurant recommendations, of course, but there are also excellent personal essays/recipes (these are not the kinds of posts where you skip down to the ingredients list! the essay parts are actually good!), highly food history articles, and—my favorite category—critical reviews that also serve as trend reports.

Earlier this month, Jonathan Nunn—the founder of Vittles—published a three-restaurant review that also examines a new tendency in British dining.

This new style was eclectic in its references, taking in Americana, French grande cuisine, Japanese ferments and nostalgia for British industrial foods. The menus blended high and low without distinction, plating produce from some of the best farms in the UK with condiments you could find on a supermarket shelf. For reasons nominally related to sustainability, whey was often involved. The naming of dishes—oysters with green glitter sabayon, rabbit glazed in fig leaf and Szechuan daikon—was irreverent, polyglottal and held a healthy disrespect for national boundaries.

Nunn doesn’t name this style (though he shares some candidates: modern global, condiment cuisine, haute leftovers) but the way he describes it—a kind of internationalist cuisine that exuberantly throws XO sauce into a French dip or Lao Gan Ma into an Italian pasta, all done in a way that feels domestic and humble and accessible—feels quite familiar in American dining too.

Nunn’s critique of this style is less the “wealth of reference points” it contains, and more about the homogeneity of the reference points—and how, perhaps, the exciting flavor combinations are covering up a certain level of technical immaturity. The review is basically a well-executed pan—in the style of Ann Manov’s review of Lauren Oyler’s essay collection. At one restaurant, located in “an airleess unit of a London Fields new build,” Nunn writes about “two dishes [that] were bad in a way previously unknown to me.” This is how he opens a paragraph about a formally innovative meatball parmigiana—the innovation being a single large meatball instead of many—that was served raw on the inside and then, after Nunn sent it back, cooked to “the texture of a Wilson tennis ball.”

This school of cooking, Nunn suggests, is typically burdened by its “fussiness, a tendency towards needless decoration and a refusal to let flavours speak for themselves, like someone anxiously trying to explain a joke they just told.” Devastating.

But Nunn’s review isn’t purely a takedown—and really, many of the best reviews are negative because they are so attached to the discipline at hand (whether it’s literature or food), and eager to see practitioners do better. Restaurants can mature over time, too. “For all their flaws,” Nunn notes, “these chefs have the…potential to change how we eat, but only if they evolve how they cook. The best thing that this Peter Pan cuisine can do is grow up.”

Self-sabotage

One thing I’ve noticed about advice on writing: It’s often very boring. It’s boring because the things you have to do are very boring and obvious: You have to start projects, and you have to finish them, and then you have to submit them or publish them.

And yet. We don’t always do the obvious things. Why not? That’s the subject of R Meager’s profoundly insightful and useful Substack post, which is 10% about academia and 90% about a form of self-sabotage that exists in all industries: Not submitting your work, not publishing your work, not doing the things you obviously must do if you want a career.

“Failing because you took a series of actions that would inevitably produce failure,” Meager notes, “is a surprisingly common feature of adult life.” And it doesn’t just happen with our jobs:

People who want to be in relationships but refuse to do online dating or speed dating or join a book club or give their number to a stranger in a bar. That’s self-sabotage. Or how about people who want a loving, emotionally available partner but marry a workaholic or some other kind of avoidant personality. Or they do find that relationship, but they cheat on the person, or are so unkind and unloving that the person leaves. There are parents who want their kids to call them, but say cutting or judgmental or overbearing things when they do. Lonely people who want closer friendships, but who don’t text the friends they have; or they text them, but they don’t tell them the truth about their lives or show them who they are. All of this is sabotage. It’s everywhere. We like to hear stories where this is the middle. In real life, there are stories where this is the end.

I have been the lonely person that Meager is writing about—I’ve felt lonely and also somehow incapable of doing the things that would help ease that loneliness, and even solve it. When I think about that period in my life, I feel a certain sense of pain—so many little acts of self-sabotage! I’m lucky to not feel that way anymore—but it’s not just luck; it also required a change in perspective, and a change in my behaviors.

Part of that self-sabotage, btw, was because I believed that city I lived in was culturally deprived and had nothing interesting going on, and therefore I simply couldn’t have an interesting life there! Here’s the manifesto I really wish my younger self had read—

Part of the change in perspective required accepting that I couldn’t control or guarantee certain things. I could text a new acquaintance and they might not text back. I could have a nice time with a new friend and they might dislike me quite a bit, and not want to see me again. Because I was afraid of these outcomes, I simply wouldn’t text the new acquaintance, wouldn’t schedule time with a new friend—a horrible and obviously self-defeating lack of agency! I had to accept the possibility of rejection in order to give myself the opportunity for actual, rewarding connection. And this is also something that Meager analyzes perfectly:

The routine theory you hear about self sabotage is that it gives us the illusion of control. I don’t think that’s right: it gives us the reality of control. It is possible to have control in life, in the sense that it is possible to guarantee your own unhappiness. And that can be safe — if unhappiness is familiar, and even in some ways preferable, to encountering a version of yourself that scares you. The versions of ourselves we will not tolerate are powerful. I think that self-sabotage is often activated purely to retain control over whether we encounter them.

The truth is that we can’t guarantee anything. Maybe the next date will be a disaster. Maybe the next writing project will be ignored by the audience we hope to impress. But also—maybe things will go well. If we stop self-sabotaging. If we sacrifice our desire for control and certainty.

What does it mean to experience “personal growth”—that indistinct, essential thing that we keep on searching for? As Meager concludes,

[It] probably looks more like finishing your projects. Or at least understanding why you don’t want to finish them. And if you’re avoiding something, there’s a part of you that doesn’t want to do it. You need to be in dialogue with it, no matter how much it horrifies you, or how thoroughly you’ve buried that part. Enough already.…You have to press send. Finish your projects.

So that’s what I’m doing. I’m pressing send.

That’s all for June! (“That’s all,” I say, having inflicted thousands of words on you. My July resolution will be to edit a bit more rigorously!) If you’ve read any excellent books, essays, poems, &c this week—please let me know! And if you’ve read any of the works I’ve mentioned, I’m of course very interested in your thoughts.

Have a beautiful summer. It’s stone fruit season (except for the southern hemisphere). Buy some peaches and read something you’ve been “meaning to” get around to!1

About once a quarter, my girlfriend and I will text each other about how we really should, this time, finally read José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia.

how do you read so much/what is your reading schedule like?? sorry if this is a repetitive q and you've addressed it before. earnest question, i am so impressed!

also re: scent of green papaya - i feel like that feature laid the groundwork for the style that Tran later grew into. it's kind of amazing that it was all shot on a soundstage in france... and two decades later, taste of things feels like a delightful INDULGENCE. like, he's saying, i've been scrappy, let me now show off how masterful i am! love both films for very different reasons.

This is incredible, thank you. Excited to read your other posts.