What should we read in order to become intellectually perceptive, emotionally mature, self-actualized individuals? Or—if that’s too difficult a question—what should we read in order to become, at the very least, better thinkers and writers? Here’s what Lydia Davis, the great American writer and translator, recommends:

Read the best writers from all different periods; keep your reading of contemporaries in proportion—you do not want a steady diet of contemporary literature. You already belong to your time.

One failure mode, as Davis emphasizes, is to only read contemporary literature. If you’re a young woman who wants to write fiction, it’s useful to read zeitgeist-y contemporary writers like Sally Rooney, Ottessa Moshfegh, Elena Ferrante, and Mary Gaitskill—but you’d be missing a great deal by not reading Clarice Lispector and Edith Wharton. (And for nonfiction writers, the late, great art critic John Berger wrote in Confabulations about the risks of being temporally myopic: “Today most analyses and commentaries about events…start their accounts too recently.” To analyze issues like “migration and economic insecurity” as if they only began in the 1990s, Berger suggested, was to “drift towards insubstantiality.”)

But another failure mode is to be the kind of person who’s excessively dismissive about contemporary literature, accusing it of being irredeemably lesser, unambitious, and parochial in its concerns. Equally parochial, and perhaps more annoying, I’d argue, is being the type of guy who only reads James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, and Cormac McCarthy—and disdainfully believing that his contemporaries have nothing to offer him. As the literary

wrote recently, if you want to publish a novel, you need to be reading recently published work. “[W]hy,” she asks, “do you expect readers today to read your book if you aren’t even reading your peers’ books?”

To these 2 failure modes (reading only in the present, and reading only in the past) I’d add a 3rd: Reading only in a few genres, instead of venturing out. “I feel some disdain,”

confessed in her newsletter, “when I meet someone (almost always male) who claims to read only business, leadership, and personal development books.” I feel the same way! How much of the human experience is available to you if you only read books about how to scale your startup? And how are you going to be an interesting and original thinker—which, at the very least, might help you come up with an interesting business model—if you’re reading the same Cal Newport–core books that all your peers are reading?1All this to say that, in July, I kept on thinking about Davis’s advice (“Read the best writers from all different periods”), as well as my own desire to read widely—different genres in fiction, different topics in nonfiction. Here’s how the month shaped up:

Fiction: 3 novels (published in 2024, 2023, and 1835) and 1 short story collection

Academic: I finished 1 book of video game history, and ambitiously started a few other books on philosophy, political science, and art history

The category I couldn’t really name: 2 works of experimental writing (it doesn’t quite feel right to call them “novels”—you’ll see what I mean!) and 1 poetry collection

Criticism-adjacent: 1 handbook on art criticism, and 1 collection of personal-narrative-slash-lit-crit essays

Other: 1 self-help book (the much-maligned genre I can’t quit; why would you not want to help yourself feel a greater sense of certainty and courage in your life??)

Oh, and I watched 4 films, all by profoundly different directors (Éric Rohmer on a Monday, Ari Aster on a Tuesday). Below, brief reviews of the 11 books and 4 films I finished—and the usual collection of recent favorites at the bottom!

Books

Novels

I read Rachel Connolly’s debut novel Lazy City (2023), about a young woman who returns to her hometown, Belfast, to grieve after the disorienting and shocking death of her best friend. I admired how Connolly wrote about the aftermath of a loss: resisting over-explanation about how the death happened, and focusing more on the protagonist’s struggle to process the death and find a way to move forward in life. I also loved the very charming, interpersonally insightful, and funny descriptions of the protagonist catching up with old friends and old situationships. Connolly is especially good at narrating all the subtle social maneuvers that occur on a night out:

The way it’s worked out with the seating at our table, I’m trapped beside Joanne, in a conversation about the new-build flats she has been to view this week…We’ve known each other for years, but our level of conversation never seems to progress beyond this. Over time I’ve started to think there is a type of person who, no matter how much time you spend with them, you never seem to get to another level of knowing them…

The worst of it is that I can hear a better conversation happening just to my left…close enough that I can hear everything that’s being said if I tune in, but the way we’re positioned I’d have to fully turn my back on Joanne to join the conversation properly. Everyone in that conversation seems to be laughing, enjoying themselves. I’m searching for a polite way to reorient myself away from Joanne and the new-builds; I down my drink and get up to go to the bar to facilitate it.

I then read Honoré de Balzac’s The Lily in the Valley (1835, but newly translated into English by Peter Bush this year) and wrote a somewhat irreverent summary of it here:

I feel a special obligation to apply the colloquialisms of my generation (“milf,” “simp,” &c) to Balzac because I’d like to emphasize how fun he is to read—and how fun many of these late, great, canonical writers are! People read them and loved them because they were the best form of entertainment you could get, pre-TikTok (and often, I’d argue, the best form of entertainment you can get post-TikTok.)

I’d really like to read more Balzac—like one of the novels or short stories from his sweeping, multi-work La Comédie humain, which features over 4,000 characters. Here’s a lovely review essay in the LA Review of Books, by Elena Comay del Junco, about the joys of reading Balzac’s fiction; and I also liked

’s post on Balzac’s “short (and unfinished) guide to beautiful living”: Treatise on Elegant Living.I also read Rosalind Brown’s Practice (2024), which I’ve been looking forward to for a few months. I was mildly disappointed. The novel is, theoretically, everything I would like: A day in the life of a young woman with an earnest devotion to literature, featuring phenomenologically precise and excessively detailed descriptions of her state of mind, surroundings, and futile attempts to write an essay. But even I—with my immense affection for plotless novels where nothing happens—felt that there was really too little plot in Brown’s novel. The protagonist spends all day trying to write an assigned essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets and not texting her maybe-boyfriend back.

The novel is very #dark academia aesthetic in the most pure way possible—all Oxford undergraduate vibes, no real stakes or intensity. The last novel I read that was set in an Oxbridge-like environment was Jo Hamya’s Three Rooms (there’s a lovely interview with Hamya over on

), which was much more attentive to issues like class privilege, economic precarity, and the struggles of being a young person trying to build a career—and so the neutered environment in Practice, where no such considerations intrude, made the novel feel like an idealized and unrealistic “life of the mind” novel.Short stories

I finished ’s Ghost Pains, published by And Other Stories (which is quickly becoming my new favorite publisher of contemporary writing). Lots of brilliant and impeccably stylish stories—the first one, “The Party,” opens with:

The party was a failure. I can’t even tell you what a failure it was. There are no words. Only a great pain in my chest when I wake up. On the veranda. It’s better when I sit in the chair. Oh, but then I can see around. The gauzy curtains, pushed by the breeze! The glasses on the floor. Little ghosts! Last night the American walked around sniffing at them like a dog. He said, Who would leave all these dead soldiers behind? I couldn’t say. I am American as well, but lately I haven’t been feeling quit myself.

Stories like this activate the intensely curious (some would say nosy) part of me. Why was the party such a failure? The first half of the collection is basically hit after hit, like an incredibly funny story about a faintly dissatisfied woman on a honeymoon in Tuscany—

It occurred to me…that what I truly missed was being engaged. Now there’s a vacation. You can get away with anything when you’re a fiancée. One day I was a bride-to-be. The next, a smoker. Shortly after that I started jogging…

—and the exceptionally strange and delightful “Weimar Whore,” about a woman who “overdosed on the media of the interwar period…[and] couldn’t keep both feet in the now,” believing herself to be living in Weimar-era Germany and fretting over hyperinflation in appointments with her psychiatrist. I’m now quite tempted to buy the newest print issue of the Cleveland Review of Books (Vol 2.1), which features a short story by Stevens and work by several other writers I like:

, , , and . (I have a copy of vol. 1—it’s excellent.)Academic

For a forthcoming review essay—more on this soon! well, “soon”—I read the game designer turned historian Chaim Gingold’s Building SimCity: How to Put the World in a Machine, published by the MIT Press earlier this summer. The book describes how Will Wright and others created SimCity, an iconic simulation game first released in 1989, drawing on ideas from control theory, cellular automata research, and children’s educational approaches that prioritized self-directed play. Stewart Brand, the cofounder of the Whole Earth Catalog, described the book as “the best account I’ve seen of how innovation actually occurs in computerdom.”

I’ve also been picking away at a number of other books that touch on, as the meme goes, “the intersection of art and technology.”2 Some of these are research for forthcoming essays; some are simply for my own leisurely research:

The philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art, which I’ve been meaning to read for years. It’s genuinely so insightful, fascinating, and clearly argued. I really do believe in games as an art form, and Nguyen’s book offers useful ways to analyze them—not merely by comparing them to literature and film, but by looking at the distinctive qualities of games and software.

The political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Scott passed away on July 19. Seeing Like a State, his most influential book, was read and admired by fairly divergent audiences—the NYT’s obituary notes that it was read by “the free-market libertarians of the Cato Institute and the lefty theorists of the Occupy Wall Street movement.” The political scientist

’s recent newsletter post, on the influence Scott’s book had on technologists, has been a helpful reference. I also loved the historian ’s essay on the influence Scott had on him, which—as a bonus!—addresses the accusation that professors “indoctrinate” their students, and offers a more nuanced perspective on how teachers influence and guide young minds.The philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s Love's Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature, after a brief discussion on Substack Notes about Nussbaum!

Sofian Audry’s Art in the Age of Machine Learning. Audry has a fascinating background: He was a grad student in the AI researcher Yoshua Bengio’s lab in the early 2000s, when “artificial neural networks were regarded by the majority of AI researchers as a dead end,” before becoming involved in Montréal’s energetic new media arts community. The book was written in 2021, well before ChatGPT kicked off the present fervor around generative AI, but in some ways, this (relative) datedness makes the book more interesting—it’s easier to see how many recent “trends” in AI art are part of a longer history.

Not explicitly a scholarly monograph, but somewhat adjacent—the art critic, activist, and curator Lucy R. Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, about the emerging conceptual art movement. “Conceptual art,” writes Lippard,

means work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or “dematerialized.” Sol LeWitt distinguished between conceptual art "with a small c" (e.g. his own work, in which the material forms were often conventional, although generated by a paramount idea) and Conceptual art "with a capital C" (more or less what I have described above, but also, I suppose, anything by anyone who wanted to belong to a movement).

And to round this all off, I’ve been reading passages of C.P. Snow’s The Two Cultures, a book that expanded on an influential 1959 talk that Snow—a trained chemist turned novelist—gave about the cultural and intellectual divide between scientific culture and what Snow calls “traditional culture,” and which we might today think of as the humanities. This is of great interest to me, as someone who “grew up,” so to speak, in predominantly STEM environments, and then was “socialized” into the arts and humanities.

I’m not sure if I’ll finish all of these books! One thing I’m trying to remind myself is that scholarly reading often operates by different rules than Goodreads-style reading. By which I mean: I shouldn’t push myself to read an entire book just because it increments some totally arbitrary number—like my Goodreads “reading challenge” goal—that I’ve decided represents whether I am reading enough.

The goal of reading, for me, is to think more clearly, deeply, and (ideally) originally—and then write essays that contain those qualities. Sometimes that requires reading an entire book; sometimes it means reading just the specific chapter, or specific passages, that help me frame an argument.

(But I would really like to finish Nguyen’s book…and Scott’s book…and Audry’s book…)

Experimental writing

There are certain writers that activate a completionist devotion in me—their style is so strange and compelling that I need to read all their works. One of those writers is the French photographer and writer Edouard Levé, who conveniently has just 4 books.

In July, I finally obtained a copy of Leve’s Oeuvres/Works, which contains 533 descriptions of artworks that Levé has not yet produced, but might like to. (He later executed some as photography projects, and at least one as a novel.)

Here’s a selection of my favorites:

32.The instruction manual of a piece of translation software is subjected to translation, twice, by that same software, from a foreign language and back again. The work consists of a copy of the original guide alongside the pretty different, doubly translated text. [RIP Levé, you would have loved Translation Party!]

39.After drawing up a list of his thousand favorite words—nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs—a man chooses texts he doesn’t like and replaces words in them with those he does like. Twenty short, unpleasant, and sensible texts are turned into enjoyable, absurd ones. [Someone make an Oulipian website for this!]’s approach to making a documentary about Eno]

286.A text recorded on compact disc, using a new track for each sentence, is played at random. There are forty-eight thousand four hundred ways of selecting two sentences from the two hundred and twenty sentences that compose the text, ten million six hundred and forty-eight thousand ways of choosing three sentences, and two billion three hundred and forty-two million ways of choosing four. There is practically no chance that the text is read in the order it was written. [Very reminiscent of Brian Eno, or of

I also picked up a copy of Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, which seems to be one of the books that really kicked off the fragmentary, autofiction-y trend in contemporary writing (or popularized it, at the very least). Immensely readable, thanks to Zambreno’s appealingly conversational writing style, her lovely depictions of her friends, and the numerous meditations on other films and writers that inspire her. I bought my copy from Womb House Books in Temescal, Oakland, CA—my friend Eliza visited the bookstore and was incredibly impressed by the selection there. So was I. The woman who runs the bookstore is incredibly nice and also organizes author events and book clubs—you can hear about upcoming events through the newsletter

.3Poetry

Despite my deep affection for reading on a screen (sacrilegious to many, I know!), it’s not really ideal for experiencing poetry. On paper, or in person, is much better. In July, while co-writing at my friend Hua’s home and feeling exceptionally sleepy and lazy, I borrowed her copy of Victoria Chang’s The Trees Witness Everything and (perhaps too quickly) read my way through the collection. Two poems I liked:

I read Chang’s Obit a few years ago and was profoundly moved—it’s one of my favorite poetry collections! Each poem is in the form of an obituary, like “My Mother’s Teeth” and “Caretakers,” and the way that Chang pushes this template in unexpected ways, poem by poem, is so incredible. I liked The Trees Witness Everything, but didn’t feel as moved by the end of it.

I also attended the poet Adrienne Chung’s reading at Book Passage in San Francisco’s Ferry Building. Chung is exceptionally gifted at moving between subtle, psychoanalytically-inflected poems and irreverent sonnets about the trappings of contemporary life: TikTok, mommy issues, and visions of Carolyn Bessette. The poems she read were from her book Organs of Little Importance (the title is inspired by a line from Darwin’s On the Origin of Species), which I read and loved last autumn. (If you’re curious about the poems, try reading “Perfect,” also published in The Yale Review.)

Criticism-adjacent

From n+1’s table at the SF Art Book Fair, I bought a copy of Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism, which collects 25 essays and interviews about the practice, philosophy, and politics of writing art criticism. Beautifully printed, a pleasure to read, very thought-provoking.

I also read ’s The Possessed: Adventures With Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, which humorously narrates Batuman’s adventures as a comparative literature PhD student at Stanford. This is more entertaining than it sounds, since Batuman offers up entertaining descriptions of great Russian novels:

I was brought to mind of a novel I had always liked, but never quite understood: Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov (1859), the story of a man so incapable of action or decision-making that he doesn’t get off his sofa for the whole of part 1. In the first chapter, Oblomov receives various visitors…A socialite rushes in, talks of balls, dinner parties, and tableaux vivants, and then rushes away, exclaiming that he has ten calls to make. “Ten visits in one day,” Oblomov marvels. “Is this a life? Where is the person in all this?” And he rolls over, glad that he can stay put on his sofa, “safeguarding his peace and his human dignity.”

She’s also very warm, and very funny, when describing her grad school misadventures, like a summer in Uzbekistan taking intensive language classes with whimsically strange teachers:

[A] poet compared his beloved’s upper-lip hairs to the feathers of a parrot feeding a pistachio to the beloved’s lips. To help me appreciate the richness of this poetic image, Dilorom drew a picture of it in my notebook. It was terrifying.

Self-help

As a characteristically fearful person who nevertheless has to quiet those fears in order to handle life’s challenges (getting a bartender’s attention at 10pm on a Friday; finding a stranger to talk to at a reading where I know absolutely no one; asking beautiful men/women on a date)—I know that, in theory, it’s very important to not be stopped by one’s fears! However, in practice I typically want to flee from any challenging situation and curl up at home, reading a safe and undemanding book.

To indoctrinate myself into more agentic, competent, and generally courageous behavior, I am constantly reading self-help books. This month’s selection was Susan Jeffers’s Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway, which insightfully points out that basically everything in life is scary:

We fear beginnings; we fear endings. We fear changing; we fear “staying stuck.” We fear success; we fear failure. We fear living; we fear dying.

“One of the insidious qualities of fear,” Jeffers notes, “is that it tends to permeate many areas of our lives.…if you fear making new friends, it then stands to reason you also may fear going to parties, having intimate relationships, applying for jobs, and so on.” Jeffers’s book argues that life is unavoidably challenging—and that the goal isn’t to fear those challenges, but rather build trust in our ability to handle anything that we’re faced with. It’s a fairly quick read with obvious insights, but still encouraging.

I’m not sure if it’s at all obvious—but I get very anxious every time I write these newsletters (surely this newsletter is the one that will be tragically and obviously dumb, poorly-received, &c), and I need to remind myself that the fear of writing something dumb is less important than the possible rewards of putting something out there. At some point, fear becomes boring. Doing something about the fear starts to feel more interesting.

Films

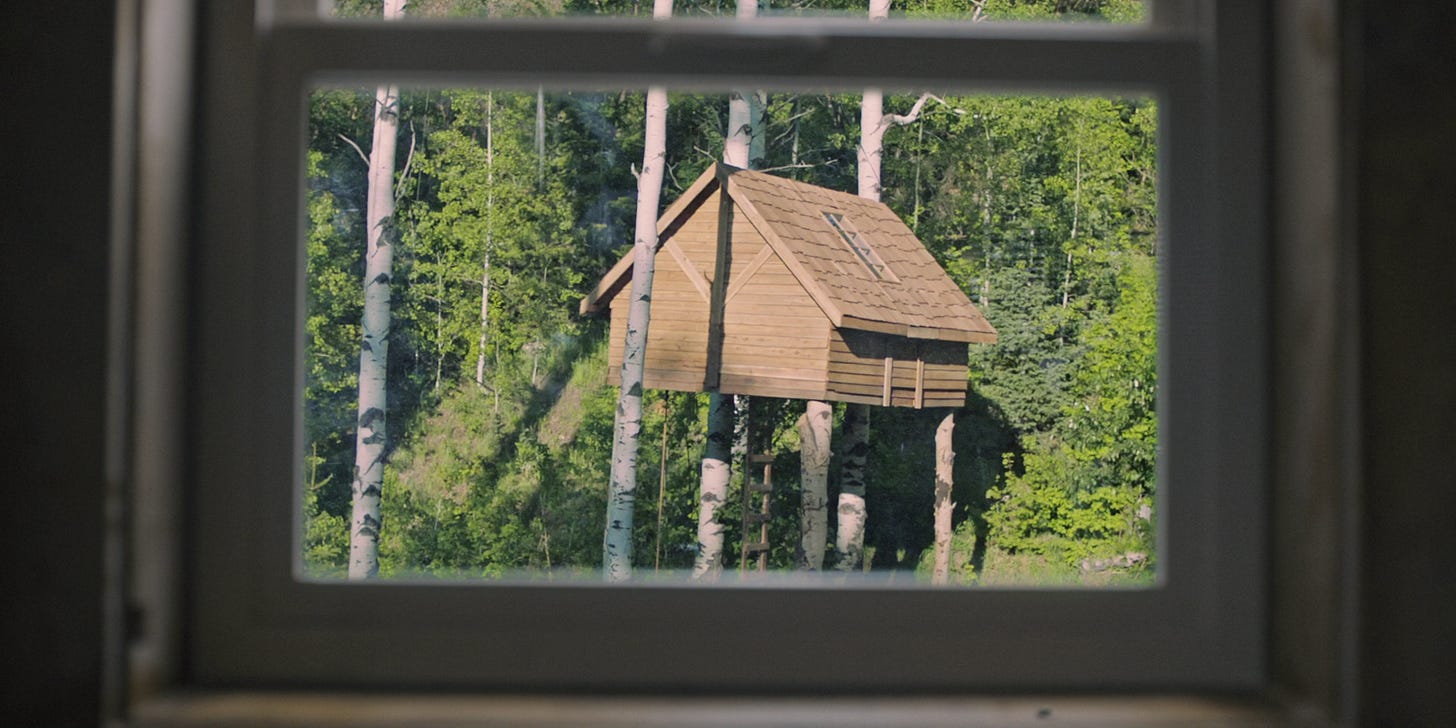

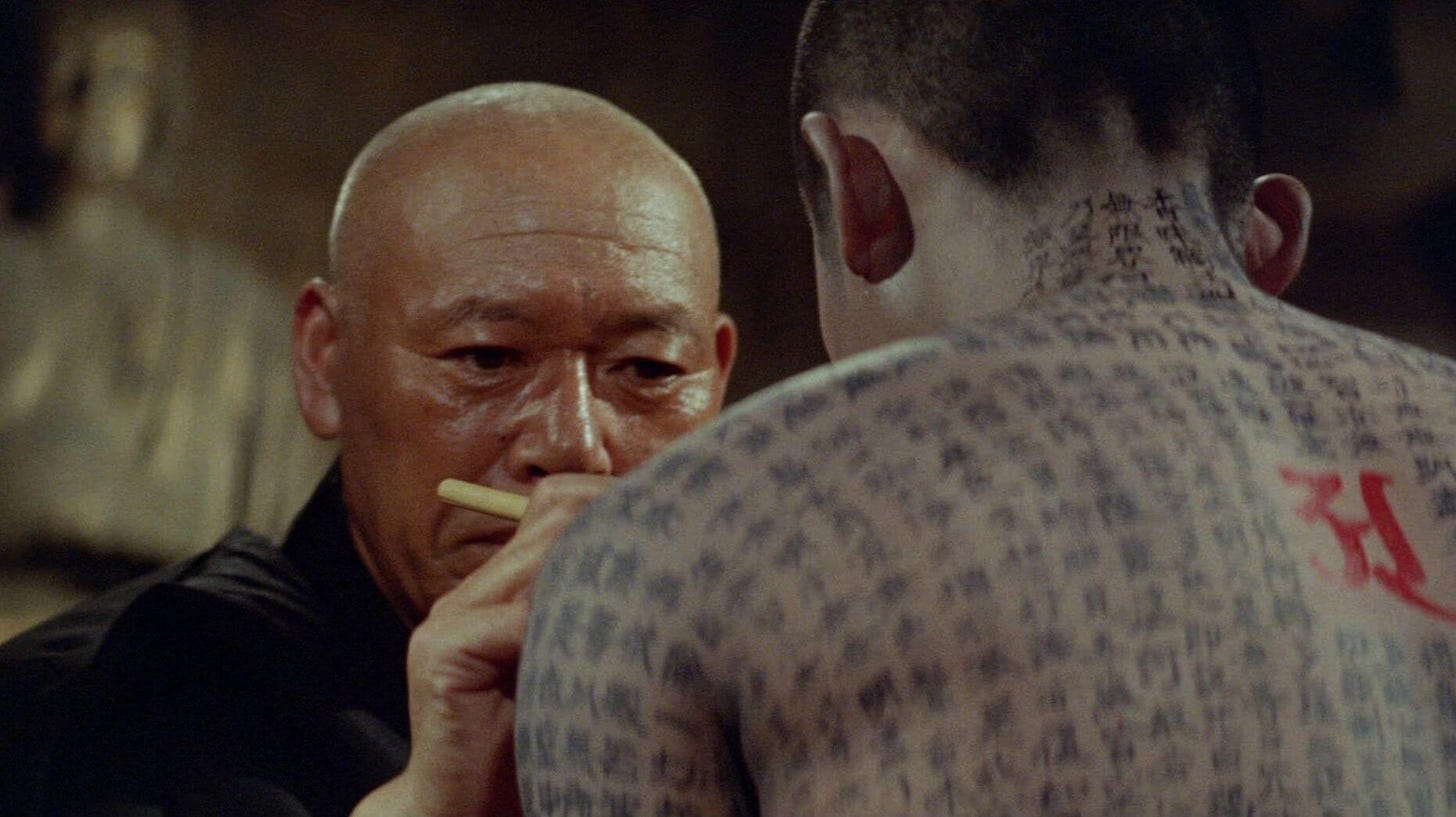

I watched Éric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (1969), about Jean-Louis, a Catholic engineer (right, in the image above) whose romantic ideals are challenged by his interactions with the glamorous, flirtatious divorcée Maud (left) and a young woman named Françoise who he falls in love with at Mass. This is my second Rohmer film, and I do really enjoy how his characters just linger around, late into the night or in leisurely midday scenes, discussing their love lives/philosophy/mathematics in extensive and obscurely charged detail.

For reasons that remain obscure to me, I then decided the perfect follow-up was Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), which opens on the morning of a an elderly woman’s funeral and slowly depicts the way in which the woman’s daughter, her daughter’s husband, and her two grandchildren are affected by her death—in typical generational-trauma ways but also uncanny supernatural-horror-genre ways. An incredibly good and incredibly terrifying film (I had trouble sleeping afterwards, tbh).

I attended one day of the Fraenkel Film Festival—11 nights of films chosen by artists represented by the Fraenkel Gallery—where I watched Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) and Akio Jissôji’s This Transient Life (1970). Both films were chosen by the photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto.

Kwaidan was just okay. It’s an anthology film with 4 Japanese ghost stories, which all felt excessively pathic and predictably plotted—except for the last one, “In a Cup of Tea.” It opens with a very particular framing device: The voiceover narration describes a collection of Japanese stories that include a number of unfinished stories. “Why were they left unfinished?” the narrator asks. “Maybe the writer got lazy…or maybe death [stopped] his [pen]?”4 The film goes on to depict a writer working on a deadline (his publisher is visiting later that day) and writing a story about a warrior who sees an uncannily cheerful face in the reflection of a cup of tea, and can’t shake off this stranger’s continual presence in his life. Both the warrior’s story and the writer’s story close in a satisfyingly horrible way. I have a great deal of affection for these stories-within-stories—it feels very modernist! But I wasn’t particularly moved by the first 3 stories in Kwaidan.

But This Transient Life—I loved this film!!! (It seems to be available on the Internet Archive, too.) The first of Jissôji’s Buddhist trilogy, the film depicts an older sister and younger brother in a well-off Japanese family and their incestuous relationship—and the various people (the family’s naive houseservant, a Buddhist monk) that are caught up in the brother Masai’s schemes. Halfway through, the film swerves unexpectedly so that it is less about sexual taboos and more about Buddhist philosophy—a swerve that I can’t even begin to describe adequately, but felt extraordinarily unexpected, unsettling, and enthralling to experience.

The film is, well, kind of fucked up. But it’s visually remarkable—there’s an opulently kinetic scene where the brother and sister chase each other around the house—and the most interestingly unsettling film I’ve seen in ages. Anyways, if you’re a Mishima reader, you should have no problem watching This Transient Life. In a 1971 review of the film for the New York Times, Roger Greenspun described it as:

evocative, ironic, lyrical, bitter, grotesque, sensuously beautiful, contemplative, active, philosophical—and — quite elaborately, lustful…the kind of imperfect, enormously ambitious movie that again and again, and at the most unlikely moments, breaks through its pretensions to a genuine complexity of vision.

I was hoping to see Gary Hustwit’s Eno (2024) documentary for the 2nd time—after seeing it at the SF premiere in May—but I didn’t buy tickets for Tuesday evening’s screening, and it’s now sold out!!!

For my May book and film reviews, see:

This is the worst thing that’s happened to me all month (which obviously means that, all things considered, it’s been a very good July. I’m reading Literature™ and I’m experiencing Cinema® and I’ve eaten twice my weight in Rainier cherries. I love summer!

Three recent favorites

What makes Norwegian literature so good? ✦✧ Ceramics for the tinned fish fans ✦✧ Trance tracks for summer ✦

What makes Norwegian literature so good? ✦

A friend of mine, currently residing in Sweden, texted me a few weeks ago to say “There are structural reasons why the Norwegians are dominating literature.” Norway has Jon Fosse, of course, the latest winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature—but there’s also Knausgaard, Vigdis Hjorth, and Dag Solstad. (I urge everyone who likes long sentences, complicated marriages, and existential crises—in literature, at least, if not in life—to read Solstad’s Shyness and Dignity immediately!)

I began to understand some of the structural reasons for all these literary luminaries after reading Ida Lødemel Tvedt’s “The Norway Model: How the Scandinavian country became a literary powerhouse.” Tvedt’s article, published in The Dial, examines what makes Norwegian literature especially appealing to international readers—and it’s an insightful portrait of how literary translation happens. One of my favorite passages:

Karl Ove Knausgård, Dag Solstad and Jon Fosse — the three most internationally acclaimed Norwegian writers alive — all have personas that fit with foreign imaginations of “the north.” Each of these writers, in his own way, is gruff, nostalgic and, one might argue, reactionary, longing for a different world, one that would fit him better. All three have a hermit vibe, eyes lit with dreams of God or Marx…Somewhere in my notes I have quoted the American critic James Wood calling them “Norwegian literature’s Little Brain, Big Brain and Galactic Brain,” but I can’t find the citation anywhere and thus suspect I have made it up. Are these long-haired neurotics Great Writers, or are they 1) really good-looking (Knausgård), 2) really good at writing opening scenes and caricaturing his contemporaries (Solstad) and 3) gnostic and icy and unapologetically boring (Fosse)? Will these authors hold up a hundred years from now? I think they might, but for now, who knows. I profoundly love books by all of them, but regarding their Greatness, the jury is out. It is like asking: Are French New Wave films good, or do they just have really nice eyeliner?

Ceramics for the tinned fish fans ✦

Good Friends is an online home goods shop that carries some of my favorite…things…like La Galine utensil rests and Brickett Davda plates (hot take: they’re better than Heath ceramics!). Whenever I feel like pointlessly generating a thing to want, I’ll do a quick browse of their website. This ceramic dish is $24 and seems like the ideal useful useless object—technically functional, but in a very specific and niche way.

Trance tracks for summer! ✦

I’ve been obsessed with “Wish Siren,” a new track from the LA-based trance DJ space master (also a friend who I admire immensely!), which opens with a faintly uncanny, almost reverential sequence of resonant echos before steadily ascending into an exuberant feeling of catharsis.

I love literature, and I love language—but there is something particularly moving about the pre-verbal art forms of music and dance. Even the greatest writers never quite access the emotional immediacy and transcendence that music can attain so effortlessly. Each art form has its particular forms of greatness. It’s humbling and exciting to be reminded of this.

I like Cal Newport, to be clear, and Deep Work is an S-tier self-help/productivity book for me. But even Newport is reading people like Edith Wharton—the 20th century American novelist who was the first woman to win the Pulitzer—and the renowned New Yorker journalist John McPhee. Many of the self-help writers copying his style aren’t doing the same!

Out of all the satirical tweets about the prevalence of this phrase, my favorite might be this one, by Christine H. Tran:

My work sits at the intersection of art & technology. It's jaywalking at the intersection. It's blocking the intersection. My work has caused a 10-car pile up at the intersection of art & technology.

Despite the word womb, it’s really not a TERF-y bookstore—when I stopped by, there were several copies of the artist and critic Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition.

I attempted to transcribe the subtitles in the Roxie Theater, in the dark, and I honestly can’t read my writing to figure out if stopped is the word I wrote down—and in the moment, I also couldn’t recall if the subtitles used the word pen or brush.

i loved this whole post and your thoughts on each piece of writing! i’m definitely in the headspace of trying to be consistent and diverse with my reading goals

Agreed! “The goal of reading, for me, is to think more clearly, deeply, and (ideally) originally—and then write essays that contain those qualities. Sometimes that requires reading an entire book; sometimes it means reading just the specific chapter, or specific passages, that help me frame an argument.”