everything i read in january 2025

4 books on religion, health, work, art ✦ and favorite links on archival practices & power

When people ask me, ‘What kinds of books do you read?’ I never know what to say. I suspect I’m not alone in this. Obviously, people tend to prefer certain books, films, songs—but I don’t know how many people will say that they just read sci-fi, only watch noirs, prefer hyperpop above all else.1 The best descriptions end up feeling very specific and very vague: Books about fatally flawed people who keep on going. Films about crushing on someone in a decadent setting. Music that feels pure and shot through with light.

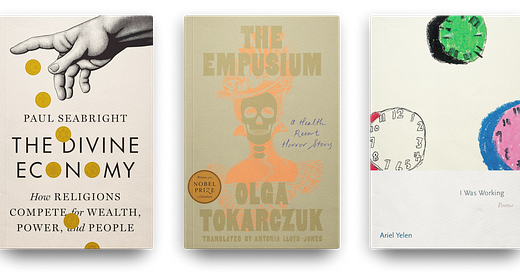

My philosophy on reading can be summed up as: Don’t discriminate, but be discerning. I’d hate to dismiss a book for the wrong reasons—but I do want to feel opinionated about what I’m reading. In January, I read 4 books: nonfiction, fiction, poetry, essays. I can’t figure out any real theme to these books (though the cover designs are predominantly beige-tan-cream-buff). I just liked them! And I think some of you might like them, too.

Below—brief reviews of 4 books in 4 different genres; 2 films about disco (as glamorous as you’d expect) and insurance fraud (more glamorous than you’d expect); and some design and music recommendations.

Also, a quick note about some other newsletter appearances:

- asked me to recommended 3 of my favorite newsletters for ‘Your favorite newsletter’s favorite newsletter.’ I was also very touched by other people’s recommendations for mine!

- has interviewed some of my favorite writers (of newsletters, essays, books), and I was delighted to be interviewed on my reading life! So if you’re curious about my reading and notetaking habits, why I think YA fiction can cultivate a lifelong commitment to literature, and (extremely personal) advice on how to read more…

Books

In January, I read 4 books in entirely different genres:

A nonfiction book about religion and economics (Paul Seabright’s The Divine Economy)

A novel (Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium)

A poetry colllection (Ariel Yelen’s I Was Working)

An essay collection (Janet Malcolm’s Forty-One False Starts: Essays and Writers)

Religions are a little bit like corporations

My first book of the year was the economist Paul Seabright’s The Divine Economy: How Religions Compete for Wealth, Power, and People. It was longlisted for the FT’s book of the year, along with

’s The Unaccountability Machine (one of the most intellectually original and exciting books I read last year! I wrote about it last September).Although many people associate modernity with a decline in religious belief, The Divine Economy opens with a great deal of empirical evidence saying that it hasn’t. Even though many religions center around beliefs that seem inconvenient, unnecessary, and easily disproven, they continue to gain adherents and influence. To understand this, Seabright argues that we can’t just look at a religion’s ideology. We have to understand how religions operate:

They recruit, raise funds, disburse budgets, manage premises, organize transport, motivate employees and volunteers, and get their message out. They do this while being keenly aware that they compete—for funds, loyalty, energy, and attention—with other religious organizations, potentially no less inspiring than they are, as well as with secular rivals and the pull of lassitude, indifference, skepticism, or outright hostility…

Religions, in short, are businesses. Like most businesses, they are many other things as well—they’re communities, objects of inspiration or anxiety to observers from outside, cradles of ambition and frustration to their recruits, theaters of fulfilment or despair to those who invest their lives or their savings within them.

Thinking of religions as businesses lets Seabright come up with unusual and fascinating ways to understand religion. He uses the concept of a platform business, for example, to explain why people don’t switch churches easily. And he observes that the Catholic Church operates with just 4 levels of hierarchy points out how remarkable it is that the Catholic Church operates with just 4 levels of hierarchy (the pope, cardinals, bishops, priests)—a surprisingly flat organizational structure. This organizational structure, Seabright suggests, was essential to the Church’s ability to expand internationally, especially in areas colonized by European powers. But it also made the Church particularly bad at handling sexual misconduct and abuse.

The book is exceptionally well-structured. Each chapter begins with a (genuinely) fascinating anecdote from Seabright’s fieldwork, which illuminates some strange or unusual quality of religion. The anecdote then sets up a question: Why have some religions lasted longer than others? What’s the right relationship between religion and politics? Why do people devote their money and time to religious institutions, and what benefits are they gaining in return? To answer these questions, Seabright incorporates research from a number of fields, including economics, sociology, history and psychology.

The Divine Economy is honestly staggering in scope; I couldn’t do it justice in my brief Goodreads review, and I’m really just scratching the surface here! But I loved reading this book, and it’s excellent for people who love big, comprehensive, Theory of Everything reads. It’s also a book that respects rigor and respects its readers: whenever Seabright incorporates quantitative or qualitative research, he’s careful to note things like the strengths/weakness of different types of data; or competing theories of certain phenomena, and why Seabright favors one over the others.

A new novel riffing off a classic

The Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story (translated by Antonia-Lloyd Jones) is about a young Polish man, Mieczysław Wojnicz, who visits a sanatorium in the mountains hoping to be cured of tuberculosis.

I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I’ve written about tuberculosis sanatoriums (and the influence they’ve had on modern architecture!) in a previous post—

The novel is Tokarczuk’s take on Thomas Mann’s great novel, The Magic Mountain, which I’ll confess I haven’t read—but Chris Powers’s review in The Guardian describes some of the similarities, including: ‘a playfully intrusive narrator…vivid descriptions of food…homoeroticism (both novels include Freudian schoolboy memories involving the fondling of pencils), two characters who engage in never-ending intellectual arguments, and a foreboding sense of European culture standing on the threshold of the slaughterhouse of the first world war.’

The novel is so immensely pleasurable to read, thanks to Tokarczuk’s great gift in sensory and psychological description. There aren’t many novelists who are exceptional at both! The sensory description helps establish, very early on, what’s so charming and quaint and—because this is a horror story, too—unsettling about the little mountain town of Görbersdorf, where Wojnicz is staying. The town is situated in a densely forested area, and Wojnicz regularly walks through the woods to gather mushrooms and be in nature:

No woods are lovelier or more intoxicating than a beech forest. At this time of year the leaves were already dark red, spreading a purple vault overhead that separated Wojnicz from the gray of the autumn sky. Silvery tree trunks supported this colossus, creating naves and chapels. The light that fell in here was mottled by the stained-glass windows of the treetops, where every leaf was like a piece of crystal playing with the light…Wojnicz walked along…[to] tabernacles hidden in holes in the trees, altars materializing on the mossy trunks of toppled beeches. This church was not at all definite, like a man-made church, but a place of constant change: of water into life, and of light into matter.

Wojnicz is staying at a guesthouse with several other men—mostly older than the young, earnestly naive protagonist—and these other characters are sketched out in humorous and specific ways. One of Tokarczuk’s translators, Jennifer Croft, has said that what drew her to Tokarczuk was ‘her psychological acuity, her ability to distill the essence of a person…and set in motion relationships that might charm and shock us at the same time, all while feeling both familiar and fresh.’

This psychological acuity is present throughout the novel—like in this description of another guesthouse resident:

He had a habit of interrupting his interlocutors…a sign of impatience toward others, which was fundamentally the driving force of his existence. He was impatient because everything fell short of his imagination and expectations, as if what he thought about the world came from other, higher realms of the spirit. Moreover, since his youth he had been sure he was unique, but somehow the world was unable to accept the fact. Everything about him said: I already know, I have long since known what you want to say. Over the years, this was joined by the feeling that he had experienced more than others—this fact gave him great satisfaction, but also locked him inside himself, for it confirmed his belief that it was a waste of time to enter into interaction with others, as they would not understand any of what he said, and he would not learn anything interesting from them. So he remained in the highly superior conviction that he was a thoroughly tragic creature.

Or in this evocative description of getting drunk:

Wojnicz was always surprised that after drinking a certain amount of the oddly savory alcohol, at first everyone was very talkative, but later on, the more of it they drank, the shorter their sentences became, and the more of them were left unfinished, as if some force were snapping off their endings, rendering their words incomprehensible…

They were all overcome by a sort of thickening feeling, which made it hard to move because of weakness or disinclination. As if the world were built of plywood and were now delaminating before their eyes, as if all contours were blurring, revealing fluid passages between things. The same process affected their ideas, and so the discussion became less and less factual, because the speakers had suddenly lost their sense of certainty, and every word that had been reliable so far now acquired contexts, entailed allusions, or flickered with remote associations.

I’ve only read 2 of Tokarczuk’s novels, but in both I was amazed by how fresh and wonderfully precise her images are. The image of the world ‘built of plywood…now delaminating before their eyes’; and elsewhere, how drunkenness often involves ‘feeling as if every movement is divided into small pieces, made up of individual pictures.’

But I don’t want to give the impression that the novel is all lovely images and character portraits. The plot is great—with Wojnicz befriending unexpected people and learning disturbing secrets about others—and the ending felt quite satisfying. Certain concerns run through the story: a reverence for nature; historical beliefs in the intellectual inferiority of women; the importance of treating sickly or unusual people with dignity. One of the most moving scenes occurs at a doctor’s office, where Wojnicz—who has felt ashamed all his life of his body—is told by the doctor:

Inside all of us there's a feeling of not being of standard value, the belief that we lack something that everyone else possesses. All our lives we must come to terms with this sense of inferiority, overcome it or harness it to the cart of our ambitions and our ruinous pursuit of perfection. But what is perfection, does anybody know?

Even a spreadsheet can be poetic

For the past few months, I’ve been reading a lot of individual poems from Loré Yessuff’s poembutter newsletter. Each email is simple, small and lovely: an image at the top, a poem underneath, and a custom color palette that draws out the beauty of the chosen artwork. (Recent poets featured: Aracelis Girmay, Steven Duong, Natasha Rao.)

I’ve loved many of the poems Yessuff recommends, so I was excited when she mentioned that one of her favorite collections from 2024 was Ariel Yelen’s I Was Working. You can read the first poem from the collection, ‘I Was Working,’ in BOMB. It opens with a striking image:

My second job was waiting in a window

behind the window of the job I was on

the clock for…

One theme running through the collection is the minute uncertainties and anxieties that hide behind the concept of work-life balance, especially for artists/writers with a day job. Here, for example, is a passage from ‘In Free Time’ on the consolations of copying and pasting in Excel:

When you’re sad it is

A relief to point

Cursor on corner

Of cell then drag it

Right, light up the page

Of little white bricks

With a square that says

These boxes will live

Be copied, pasted

Echo in excel

While others will fade

Into abstraction

Another theme is the intense pleasure and insecurity that great art inspires. I love the poem below for its directness and humility—and for using the title to open directly into the poem:

I’m depressed to only now have discovered

This great poet

Imagine if I’d discovered her earlier, I’d be rich

Oh! the poems I would not have written, inspired

By reading her

Had I read her earlier, I would’ve thought this

Is it—and the desire to write

Would drain from my body

In service of us all

And I would move on

To making money

To acting, maybe

Or farming

Or simply to being of use in some other

Less painful way

I’ll leave you with one final quote, from the perfect poem for January. In ‘New Year Poem with Green Flooding,’ Yelen writes:

The mechanics of how one

Lives life

Astound me, and yet

They’re all I’ve ever known

I don’t want the job of hating my job

I want to flood things with love

Like the green flooding in

Forty-one false starts to the year

I also read the esteemed journalist Janet Malcolm’s Forty-One False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers. The title comes from Malcolm’s 2014 profile of the painter David Salle, where Malcolm gradually assembles a portrait of Salle—his discipline, wealth, injured ego, ‘dead-serious connoisseurship,’ and ‘reckless inventiveness’—by repeatedly restarting the essay. Reading it feels like going through a museum exhibition of conventional opening strategies—something I’ve been focusing on in my own writing—and it’s exciting to see where Malcolm goes with each new beginning.

What else is in the essay collection? A remarkably insightful essay on Edith Wharton and her cynicism about women; an essay on the legacy of the Bloomsbury Group (largely focused on Virginia Woolf and her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell) and how famous figures are remembered by their families; an essay on Gossip Girl, which I wrote about in my previous post:

Reading Forty-One False Starts reminded me of why essays are so exciting—and how much a great writer can do with them.

Films

Early on in January, I watched Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco (1998) at a screening in London with a director Q&A after. The film is about two young women working in publishing—Charlotte (left), compulsively cruel and seemingly self-assured, and Alice (right), who feels like the heroine of the film—and their nights out at a Studio 54-esque disco club in NYC. Last Days depict the kind of shimmering, exuberant joy of dancing and meeting people who become friends, enemies, lovers…but there are also very realistic scenes of Alice waiting nervously for someone to speak to her, and awkward conversations between friends who don’t really like each other!

The Last Days of Disco was Stillman’s third film. In the Q&A after the screening, Stillman said that some of the most ‘pleasant’ days working on his second film, Barcelona, ‘were the days we were shooting at the disco…I thought that two beautiful girls dancing…could be really cinematic.’ And so: The Last Days of Disco, with all the beautiful shots of people dancing against a dark, glittering background. The film also has such a delightful verbal dexterity: there’s so much talking, so many intelligent and funny and cheeky lines.

For the film and fashion nerds: I enjoyed

’s interview with Loreta Lamargese, a gallery director who happens to own the specific top that Kate Beckinsale’s character wears in the film! The interview touches on what they both love about the film, with Lamargese saying:I was embarrassingly late to Last Days of Disco. It’s one of those movies I always thought I’d seen but had probably just accessed through Tumblr images. My first watch was on a casual at-home movie date with my fiancé…He’s often embarrassed he’s missed film canons, whereas I have a silly minor in cinema which forced me to have seen a lot. But in this case, we were both like, ‘how did we get this far without having watched it?’

Obviously, I loved it. Chloë Sevigny to me is New York, so it makes total sense to put her through the cinematic time machine and have her occupy the most iconic slices of NY history, like Studio 54. I think we hold an idea of these histories as pristine and pure, in contrast to our present which is always already under occupation by some infiltrating force. So it’s a smart and funny move to have the story begin at the end, when the whole thing is crumbling and these girls are clawing their way into something that’s already over.

For some reason (tremendous laziness about leaving the house in January) I didn’t go to see any newer films: Babygirl (my friends had mixed reviews), The Brutalist (the reviews here are decidedly not mixed and I really want to see it!)…

But I did have a little film night at home devoted to Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), a film noir produced during the Hays Code era, when Hollywood strenuously avoided showing profanity, nudity, and other ‘perverse’ and immoral content. The film, though, is about a wealthy woman’s affair with an insurance salesman, and their plot to murder the woman’s husband and collect a life insurance payout together.

What’s remarkable about Double Indemnity is that it makes the attraction and tension between Stanwyck and MacMurray feel very compelling—you do see how MacMurray would risk his job for it!—without showing a lot of physical contact between them. My fiancée found the film through the critic and essayist

’s excellent newsletter on cinematic sensuality and accompanying film recs on Letterboxd. After watching one film on the list, I now trust Bastién’s recs completely. Maybe a good list to go through for Valentine’s Day?Image, text, sound

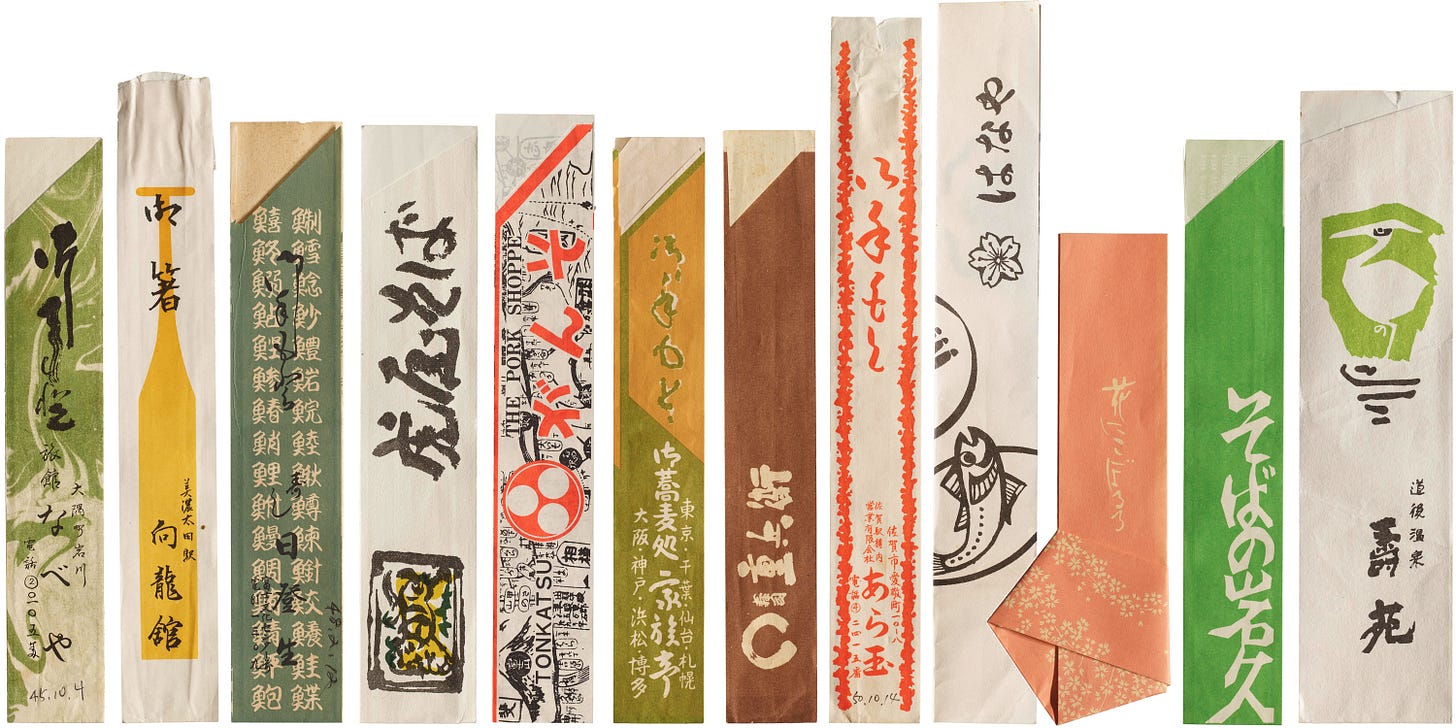

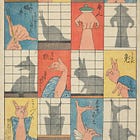

On personal archives and graphic design. In a gift to graphic designers everywhere, the Letterform Archive has scanned 500+ Japanese paper chopstick sleeves (above) donated by Susumu Kitagawa. Writing for the Letterform Archive’s blog, the designer and professor Angie Wang described them as ‘emissaries of Japanese typography and culture.’ Personal archives are a wonderful way to preserve ephemeral design artifacts—another delightful example of this is

’s project to scan 200+ lai see (below) and share the wide range of designs.

On power. I’m starting to think that the best ‘scene reports’, if you want to understand how political/technological power operate, come from conference reports, not party reports. For The Baffler’s January issue, Megan Marz attended an HR tech conference to see how companies are responding to—and sometimes exacerbating—concerns about hiring bias, income inequality, and AI’s impact on jobs:

I scanned into a room where the president of an ATS maker was going to talk about AI’s effects on job candidates…I thought the ATS guy might finally give me some insight into the inventions of his heedless ilk, the ones causing all that distress back out in the world.

I was taken aback when he started speaking, because he did not actually seem heedless at all. Unlike most of the speakers I heard before and after him, his descriptions of workers’ concerns seemed rooted in reality, rather than the wishful projections of technology companies…He didn’t have to say structural problem to bring me back to the reality that this was one.

For him, of course, it was a business opportunity. He was part of what I would come to see as a savvy minority of people and companies capitalizing on AI fatigue. I was beginning to feel it myself: the conference was oversaturated with more than forty AI sessions. Greenhouse was introducing features designed to help with problems AI had supposedly exacerbated.

And I’m still thinking of the journalist

’s ‘Live Free or DEI’ from last September (the iconic headline helps!), where Del Valle attends a pro-natalist conference to trace the disturbing alliances between anti-DEI academics and eugenicists who insist on a racial hierarchy of intelligence. More on this in Del Valle’s newsletter about researching and writing the piece!On music and place. For the technologists frantically catching up on China’s latest AI innovations—maybe you can catch up on Chinese musical trends as well? I love reading

, a newsletter about mostly independent/alternative music from China, and I enjoyed this recent installment on Douban’s favorite albums of 2024. They really like Jay Chou and…Clairo? I also enjoyed this Chinese shoegaze recommendation:Thank you, as always, for reading. This month’s books, films and links roundup is arriving a week later than planned—but I’ll be in touch soon! The next few newsletters you’ll receive will touch on:

Anti-algorithmic music recommendations (and Liz Pelly’s excellent new book, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist)

Meeting people online/becoming friends offline

Discussing literature and diversity with integrity (and what that meant in 2015 versus 2025)

…and an interview with an essayist that I admire tremendously!

I really do love hyperpop, though! It’s the genre of music that makes me feel like I’m mainlining caffeine and can take on anything in life.

Excellent thanks - some great recommendations… I’m now listening to the Chinese music

Finding that I’m really starting to look forward to these m!