everything i read in february 2025

3 novels and 2 films on love, despair, and loss ✦ and how to read Hannah Arendt for the first time

Some of the most meaningful experiences in life just aren’t very fun. It feels bad to say that, like a betrayal. We want meaning and joy to be inextricably linked; we also want goodness to come with beauty, and ethical behavior to always be rewarded. But what if it isn’t? (It often isn’t.)

Comfort reads, for me, are narratives that avoid these conflicts. The hero pursues a dream and succeeds, ultimately sacrificing nothing: They’re loved, admired, wealthy, happy. This basic plot appears in a lot of mediocre writing, but also a lot of great writing—Jane Austen’s marriage plots; Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You; Lily King’s Writers & Lovers; Banana Yoshimoto’s novels. These novels often steer their protagonists through treacherous ground—financial precarity, the grief of losing a parent, and enervating mental health struggles.1 Which is why the happy ending, once it arrives, feels hard-won and necessary. Why should a fictional character’s life be hard? Why shouldn’t they get everything they want?

It’s comforting to read about characters who don’t have to compromise, don’t have to choose. But straightforward love stories have their limitations, as the novelist Adelle Waldman, in an essay for the New Yorker, observed:

Lionel Shriver argued that “fiction writers’ biggest mistake is to create so many characters who are casually beautiful.” What this amounts to, in practice, is that many male characters have strikingly attractive female love interests who also possess a host of other characteristics that make them appealing. Their good looks are like a convenient afterthought.

This is, unfortunately, sentimental: how we wish life were, rather than how it is. It’s like creating a fictional world in which every deserving orphan ends up inheriting a fortune from a rich uncle.

All this to say: in February, I read books and watched films about conflicts that appear in love and romance. Not very cheerful, is it? But sometimes what I want from art isn’t comfort, but catharsis: I want something that understands how difficult life can be, and how seriously we have to approach it. Below, brief reviews of:

3 novels on love and despair—Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina, Eva Baltasar’s Permafrost, Antonio di Benedetto’s The Suicides (all translated!)

2 films on thwarted desire and jealousy—Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (after the Thomas Mann novella), Chantal Akerman’s La Captive

The other theme of my February was the difficulty of doing personally meaningful work! And so I read:

1 philosophy book on labor, work and action—yes, it’s Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition

2 artistic self-help books—for those determined to write and put their work out there, but struggling with procrastination and self-consciousness

Novels

There’s really no good way to describe Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina, so let’s start by describing Bachmann herself. My copy of the novel included a very good introduction written by Rachel Kushner, who first heard about from a man who called Malina “a very important work by a major Austrian writer.”

In “important” and “Austrian” and “work,” I computed that its author, a woman, was in fact an honorary man…The way he announced the existence of Ingeborg Bachmann suggested that he believed, consciously or not, that she belonged to the world of men; perhaps she even derived from it. Anything is possible. Whether consciously or not, I put a claim on her, as someone to study, on account of her status as an honorary man.

But the novel itself is very much about being a woman in a man’s world. The protagonist is a woman living with one man (Malina), having an affair with another (Ivan), and haunted by disturbing memories of her father. It’s not totally clear which events of the novel are real or imagined—it feels like the woman’s psyche is on the verge of collapse—but once I accepted this, it was an incredibly fun read!

Bachmann has such a disorienting, enthralling style—here’s a good example of it:

I also read the Catalan poet Eva Baltasar’s Permafrost, translated by Julia Sanches. I love reading novels by poets—they handle language in such inventive and irrepressibly playful ways. Permafrost is about a young lesbian woman who wants to die and also wants to sleep with as many women as possible; it is, as a result, helplessly funny and genuinely pathic. It’s a quick read, full of quotable moments, and some very touching familial dynamics. The protagonist feels misunderstood from her mother and sister, but—towards the end of the novel—she develops an unexpected rapport with her niece, leading to some very touching scenes of intergenerational care.

My last novel of the month was the Argentinian novelist and journalist Antonio di Benedetto’s The Suicides, translated by Esther Allen. It’s an charmingly picaresque novel about a young journalist asked to investigate 3 suicides. He does so doggedly but also distractedly; much of the novel is taken up with his various flirtations, as he languishes after different women (especially Marcela, a photographer working at the same news agency) and laments how everyone seems to be in a relationship already. And he’s brooding: as he investigates the suicides, he can’t help but think about his father, who committed suicide at 33—the age that the journalist is approaching.

The Suicides is admirably balanced, always, between meditative pathos and humor. It ended up complementing Baltasar’s Permafrost perfectly, as both revolve around depression, romantic disinterest (and somewhat heartless protagonists), and difficult family relationships.

I should note, too, that it’s the NYRB Classics Book Club’s February selection—one of my favorite ways to discover new books, as I wrote about for One Thing last year:

Philosophy

Hannah Arendt is one of those great writers that—for many years—I’d never read, just read about. Back in 2021, I read At the Existentialist Café by Sarah Bakewell (here’s my brief Goodreads review), which touches on Arendt’s early life and education, her relationship with Heidegger, and her key works. And later, in 2023, I read Deborah Nelson’s Tough Enough (one of my favorite nonfiction books of the year!), which has a whole chapter on Hannah Arendt’s style and ideas. This kind of reading-around an intimidating intellectual figure is very useful, I think—it’s a way of working up the courage to actually approach them.

But when I—finally!—read Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition this February, it was because I’d learned a few other tactics for reading books that seem difficult and imposing:

Create an arbitrary emergency. When the Arendt scholar Samantha Rose Hill posted ‘An invitation to read The Human Condition,’ where she invited others to read Arendt’s 1958 book in January, I realized that having an arbitrary deadline would finally make it possible for me to read the book. I didn’t quite make it—I finished on February 1—but if not for Hill, I wouldn’t have started the book at all!

Don’t read alone. Hill promised weekly talks on the book (posted as videos in her newsletters) and Zoom calls for those who could make it. I never ended up joining the Zoom calls, but the videos were quite useful! And whenever I read through a difficult passage, I told myself that someone, somewhere on the internet, surely had an explanation that would help me. (As usual, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy had a useful, if dense, explanation of the book.)

Do it out of love and curiosity, not out of obligation. Arendt is better known, I think, for The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem. I’ve checked out both from the library multiple times, and never managed to read them—they felt like obligations, especially in that sickeningly anxious, politically activated 2016–2020 period in American politics. Ultimately, I read The Human Condition because my friend nikhil had sent me Nathan Becker’s blog post on Hannah Arendt and living a wasted/active life. I loved Becker’s introspective, very personal discussion of Arendt’s ideas, and how he applied them to thinking about design (the profession we share!)

So: What’s the book itself like? Well, it’s a hard book to sum up—she touches on so much (including: the problems of modernity; old/new definitions of privacy; the unpredictability of political action). But here are 5 memorable things I got from it:

Arendt’s arguments are very rooted in Greek and Roman conceptions of the good life. She begins by criticizing the idea that the vita contemplativa (centered around introspective inaction) is better than the vita activa (which Aristotle and others treated as a negative example of being too restlessly active). Arendt champions the vita activa, which for her has 3 parts: labor, work, action.

Labor is anything you do to sustain your life on a basic, biological level, like eating. Work is something you do to make a more durable, extrinsic thing: designing and building a chair, for example. Action, for Arendt, is specifically political action, and is inherently a public and social act. You can’t act in isolation; you’re always acting in situations full of other people, who can respond to your action by debating, agreeing, disagreeing, enacting, blocking, &c.

For Arendt, labor is necessary but dull work that makes humans just like any other animal. Work involves more distinctive human traits and the creation of more enduring meaning—designing a chair, for example. But action, to Arendt, is to be the thing that makes human life significant and important.

She has an extremely funny passage where she basically says: I’m about to criticize Marx, but I’m not like other Marx critics!2

She also has a beautiful passage on how poetry, of all the art forms, is the “closest to thought.”3

Artistic self-help

I’ve written before about reading philosophy books as self-help, but I’m also an ardent reader of, well—ordinary self-help books! In February, I read 2 very useful books on writing more and sharing more work.

The first was Hillary Rettig’s The 7 Secrets of the Prolific (usefully subtitled The Definitive Guide to Overcoming Procrastination, Perfectionism, and Writer's Block). Rettig begins by saying that, for her, a “prolific” writer isn’t someone who’s achieved “some fixed arbitrary standard of productivity, but someone writing at their own full capacity.”

What prevents someone from writing at full capacity? Procrastination. But where does the procrastination come from? It comes, Rettig suggests, from a “self-abusive litany” that makes people afraid of failure (or afraid that, perhaps, they’ve already failed) and the consequent “ego demolition” that will result. Rettig’s book very usefully describes some of the emotional triggers for procrastination, and the concrete actions that help someone enter a more “compassionately objective” state, where they can write easily and take the quality of their work seriously—without falling into a disastrously self-critical mindset. It’s a really useful book, and I have to thank john d. zhang for recommending it to me!

In turn, I’d like to recommend his excellent essay from last May about the unfair and painful aspects of romantic love—

I also read Austin Kleon’s Show Your Work!, a book that is exactly as long as it needs to be (this is high praise!) and dense with generous, useful ideas.4 The book, subtitled 10 Ways to Share Your Creativity and Get Discovered, is about how to share your work online when you really, really hate self-promotion. Kleon’s advice, to the compulsively shy, is to abandon the belief that work must be perfect—and, indeed, that we must be fully formed as artists/writers/musicians/&c—before it can be shown. Sharing what we’re working on, Kleon writes, can help us find community and advance our work:

Writer David Foster Wallace said that he thought good nonfiction was a chance to “watch somebody reasonably bright but also reasonably average pay far closer attention and think at far more length about all sorts of different stuff than most of us have a chance to in our daily lives.” Amateurs fit the same bill: They’re just regular people who get obsessed by something and spend a ton of time thinking out loud about it.

One of my favorite ideas in Show Your Work!—perhaps because it so closely reflects my own approach to writing this newsletter—is the importance of sharing your reference points. “We all have our own treasured collections,” Kleon writes, whether it’s physical collections of novels and records, or “mental scrapbooks” that shape our taste and work. All this, Kleon stresses, is worth sharing and attributing properly:

Your influences are all worth sharing because they clue people in to who you are and what you do—sometimes even more than your own work…

If you fail to properly attribute work that you share, you not only rob the person who made it, you rob all the people you’ve shared it with…Attribution is all about providing context for what you’re sharing: what the work is, who made it, how they made it, when and where it was made, why you’re sharing it, why people should care about it, and where people can see some more work like it. Attribution is about putting little museum labels next to the stuff you share. Another form of attribution that we often neglect is where we found the work that we’re sharing. It’s always good practice to give a shout-out to the people who’ve helped you stumble onto good work…I’ve come across so many interesting people online [this way]…I’d have been robbed of a lot of these connections if it weren’t for the generosity and meticulous attribution of many of the people I follow.

Films

I watched 2 films this month—both film adaptations of early 20th-century literature! The first was Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971), a film adaptation of the Thomas Mann novella. It always takes me a while to enter into the world of an older film—the cinematography, the dialogue, the use of music all feel very different! But once I settled into this film, about a composer visiting Venice for a recuperative holiday, I was quite moved. The composer ends up falling in love with a young boy at the same hotel, but grows increasingly agitated by the strength of his passion and the anguish of feeling that his affection is immoral and futile. A beautiful film—if you can enjoy an aestheticized misery.

The second film was Chantal Akerman’s La Captive (2000), a film adaptation of the fifth volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. This was a difficult film for me! I love Proust (and probably mention him in every newsletter I send), and I’m very drawn to Akerman’s work…but this was my least favorite volume of Proust’s novel! Unfortunately, this meant that La Captive, which depicts the protagonist and his love interest (Albertine in the novel, Ariane in the film) in a claustrophobically paranoid relationship, was just—not fun. Akerman perfectly captures how it felt to read The Prisoner, with its agonizing, repetitive depiction of a love affair getting worse and worse.

But here’s what I did love: the opening scenes and the very charming dialogue; the color palette of the film (just consistently extraordinary); the realization that I have a very specific image of some of the characters of In Search of Lost Time and the mannerisms I expect from them. (The actress playing Ariane/Albertine was much more timid than I imagined she would be!)

Articles

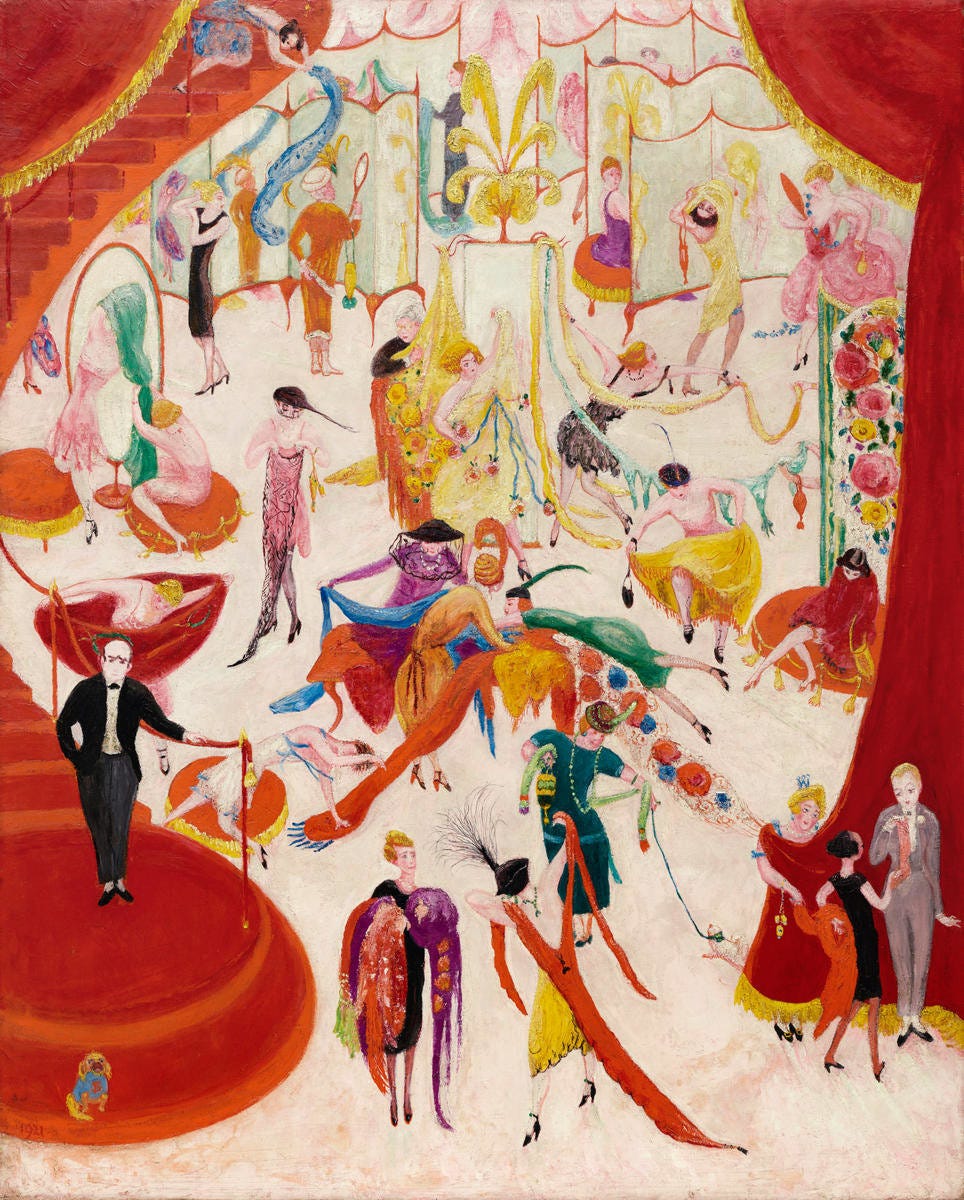

On painting. A recent newsletter from the critic and essayist BDM convinced me to change my phone background to a Florine Stettheimer painting. (The monied buy her paintings from Christie’s; the rest of us admire them in museums or on our screens). Here’s a lovely essay from Adam Gopnick about the “luxury and ecstasy” of Stettheimer’s seemingly ingenuous paintings:

Stettheimer’s deliberate simplification of drawing, her repetitive figure style, and her relentlessly additive, crowded compositions can at first evoke “outsider art.” But there are two types of outsider art, one made from below and one from above. There is the outsider who is, at first, indifferent to the possibility that money might be made from art, and then there is the outsider who needs to make no money from her art…Stettheimer, like Proust, her beloved literary hero, enjoyed the detachment provided by wealth, the luxury—shared by Edith Wharton, Gerald Murphy, and Cole Porter—of making what she wanted.

If you want to read more about Stettheimer, I also loved Johanna Fateman’s review of a Stettheimer biography for 4Columns.

On Charles Atlas and capturing dance in film. I’ve started reading more art and film criticism, which, unlike literary criticism, has the challenging—and ennobling—task of translating images, color, sound, and motion into a sequence of relatively still, placid sentences. The art critic Jennifer Krasinski is brilliant at this—I loved her review of the moving image artist Charles Atlas’s exhibition. Atlas collaborated with Merce Cunningham, Leigh Bowery, Yvonne Rainer, and other influential figures in dance and performance. The review is awash with exuberance and genuine pleasure, and I loved the ending:

Though Atlas is not strictly speaking a documentarian, his work is also an archive from times of great cultural courage. Memory is short for most things, but I remember the year Giuliani became mayor of New York in 1994. One of his first orders of business: dust off an old law that made dancing illegal in venues that didn’t hold a cabaret license. You couldn’t even wiggle your ass in front of a dive-bar jukebox without getting shouted at by the bartender. Though that time has now passed, a part of me has held on to the belief that public expressions of joy are inherently acts of insurrection. This may explain why I felt a rush of hope for the future—the first I’d felt in some time—when, in Atlas’s video, the sun set and the lights came up on a shot of Bunny in an off-the-shoulder evening gown, her wig cascading like a champagne fountain. A beat with a brass section kicked in, and, as she began to strut and sing, two visitors sitting on a bench in the gallery got up and started dancing.

On the energy transition (if we can manage it). The nice thing about having a newsletter is that I don’t need to justify (well, too much at least) a sharp turn from art to climate. A colleague shared this article from Foreign Policy’s February issue, which soberly considers why we’re experiencing record highs in renewable energy usage—and simultaneous highs of oil/coal usage:

What has been unfolding is not so much an “energy transition” as an “energy addition.” Rather than replacing conventional energy sources, the growth of renewables is coming on top of that of conventional sources…This was not how the energy transition was expected to proceed. Concern about climate change had raised expectations for a rapid shift away from carbon-based fuels. But the realities of the global energy system have confounded those expectations, making clear that the transition—from an energy system based largely on oil, gas, and coal to one based mostly on wind, solar, batteries, hydrogen, and biofuels—will be much more difficult, costly, and complicated than was initially expected.

On the economy. Eugene Ludwig’s insightful “Voters Were Right About the Economy. The Data Was Wrong”, for Politico, explains how economic indicators like the unemployment rate, weekly earnings, inflation (measured with the CPI), and GDP are measured—and why he believes they fail to capture America’s lived economic reality.

For 20 years or more, including the months prior to the election, voter perception was more reflective of reality than the incumbent statistics…[which] paint a much rosier picture of reality than bears out on the ground.

On Gen Z’s double disruption. kyla scanlon has an excellent deep dive on Gen Z’s perceptions of the economy, and how young people are reacting to the “double disruption…of AI-driven technological change and institutional instability” that makes conventional career paths much more unstable than a generation ago (or even a half a decade ago!).

Thanks for reading, as always! For regular readers: my apologies for the lack of newsletters in February…but I’d always rather show up in your inbox with something worth saying!

Hope you’ve had a February full of affection and care, and that March is good to you.

I’ve really been looking for an excuse to throw enervating (something that drains your energy, exhausts you of your vitality and joie de vivre) into a newsletter!

Here’s the Arendt passage, at the beginning of The Human Condition’s chapter 3, ‘Labor’:

In the following chapter, Karl Marx will be criticized. This is unfortunate at a time when so many writers who once made their living by explicit or tacit borrowing from the great wealth of Marxian ideas and insights have decided to become professional anti-Marxists…

In this difficulty, I may recall a statement Benjamin Constant made when he felt compelled to attack Rousseau…“Certainly, I shall avoid the company of detractors of a great man. If I happen to agree with them on a single point I grow suspicious of myself; and in order to console myself for having seemed to be of their opinion…I feel I must disavow and keep these false friends away from me as much as I can.”

I find this very funny (if discreetly so) and charming!

From Arendt’s The Human Condition, chapter 23, ‘The Permanence of the World and the Work of Art’:

Poetry, whose material is language, is perhaps the most human and least worldly of the arts, the one in which the end product remains closest to the thought that inspired it. The durability of a poem is produced through condensation, so that it is as though language spoken in utmost density and concentration were poetic in itself…

Of all things of thought, poetry is closest to thought, and a poem is less a thing than any other work of art; yet even a poem, no matter how long it existed as a living spoken word in the recollection of the bard and those who listened to him, will eventually be “made,” that is, written down and transformed into a tangible thing among things, because remembrance and the gift of recollection, from which all desire for imperishability springs, need tangible things to remind them, lest they perish themselves.

In contrast, a book that I think is far too long is Rick Rubin’s The Creative Habit. Books that aren’t particularly idea-dense frustrate me—it feels like they don’t respect the reader’s time enough. But one of the most useful things I got from The Creative Habit is Rubin’s emphasis on releasing work into the world at the right time, instead of hesitating and revising it forever:

When you believe the work before you is the single piece that will forever define you, it’s difficult to let it go. The urge for perfection is overwhelming. It’s too much. We are frozen, and sometimes end up convincing ourselves that discarding the entire work is the only way to move forward. The only art the world gets to enjoy is from creators who’ve overcome these hurdles and released their work. Perhaps still greater artists existed than the ones we know, but they were never able to make this leap. Releasing a work into the world becomes easier when we remember that each piece can never be a total reflection of us, only a reflection of who we are in this moment. If we wait, it’s no longer today’s reflection. In a year, we may be guided to create a piece that looks nothing like it. There is a timeliness to the work. The passing of seasons could dissipate the value the work holds for us.

i look forward to your monthly roundups each month!!

Lovely round up!