February! The month of love, love letters, eavesdropping on first dates at wine bars, spending too much money on books, and getting caught in a rare San Francisco rainstorm.

This month, I read 11 books, watched 1 film (Trân Anh Hùng’s The Taste of Things), and indulged in a moderate amount of consumerism: this lipstick from Byredo, and these placemats (with a silkscreen floral and checkerboard print) because I’d like to invite friends over for dinner more often! To me there is no greater act of love, platonic or romantic, than cooking for someone. A future post…?

But for now—some brief reviews of the books, essays, tweets, and music, and design artifacts I encountered in February!

Books

I read 11 books this month:

3 nonfiction books

1 essay collection from my NYRB book subscription

1 graphic novel from my New Directions subscription

2 book-length essays

1 historical fiction novel

1 artistic self-help books

and 1 ordinary self-help book that wasn’t…that good…

Nonfiction ✦

I read two books about cultural consumption and taste:

Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture, which discusses how algorithmic discovery on platforms like Netflix, TikTok, Spotify, and Instagram have changed our cultural consumption and tastes

David W. Marx’s Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change, which is a masterfully accessible and rigorous book about how cultural consumption, trends, and taste are informed by status-seeking behaviors

Both books manage to be very readable and friendly, while still referencing a wide range of theorists, critics, and sociologists—including Pierre Bourdieu and his 1979 magnum opus Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Bourdieu’s book is foundational to discussions of economic versus social versus cultural capital; how we define “high culture” versus “low culture”; how class position impacts your relationship to avant-garde art and aesthetics; and so many other topics I’m deeply interested in! I’ve been meaning to read it for a few years, and now feels like the right time—finally. I’m reading it for a very informal book club with two friends in San Francisco. If you’re reading it as well or want to share anything you particularly liked/disliked about it, please reach out!

I also read L.A. Paul’s Transformative Experience. Paul is a philosophy and cognitive science professor at Yale, and her monograph is about how we choose experiences that change us on a fundamental level—how we see the world, what we value, and what we enjoy. Examples of transformative experiences might be:

Eating something that has a novel, unprecedented flavor: We can’t know in advance whether we’ll like it or hate it. (Paul uses durians as an example; they’re such a deeply polarizing fruit, and other people’s experiences with them seem to offer no model for whether you might enjoy them)

Making a lifelong commitment (such as marriage) to someone: Doing so assumes that we will remain in love with each other not just for this day, or this week—but for a much larger expanse of our lives. But how can we decide if we want to commit, given that we don’t know who we’ll be in 10 years, much less our partners?

Choosing to have kids: There’s really no way to simulate what having kids is like, much less the specific kid that we might have and raise. Since this decision irretrievably affects your life and the child’s life (and other people, like a partner and family), shouldn’t you try and make the most informed decision possible? But how can you do so when you’ll never fully know what having kids is like until you do it?

Paul’s book is a meticulous and fascinating examination of why these kinds of experiences are so hard to make perfectly rational, informed decisions about. But she proposes a method for making decisions anyway: instead of trying to figure out what’s 100% good or bad for you, you can instead recognize that such experiences are intrinsically valuable, because they reveal something new to you, and then decide whether you want that revelation or not. This is a crude synthesis of a very interesting book—but if you’re interested in epistemology, phenomenology, and decision theory, I recommend this! It also pairs very well with Agnes Callard’s Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming, which is one of my favorite philosophy books.

Essay collections ✦

Earlier this month I wrote about book subscription services for One Thing. They’re offered by three of my favorite independent publishers (Fitzcarraldo Editions, New Directions, and NYRB Classics) and are a really lovely way to experience great literature and great graphic design:

This year, I’m subscribed to the New Directions and NYRB Classics subscriptions. The NYRB’s January 2024 selection was Cristina Campo’s The Unforgivable and Other Writings, which was electrifyingly good. The best moments in life (for a reader, at least) are when you find a great writer that was totally unknown to you before picking up their book, and the sheer force of their style—and the strength and power of their worldview—impresses itself upon you with every sentence.

The essays touch on myths and fairy tales (in a very psychoanalytic, Jungian way), Chekhov’s short stories, Proust, Catholic monks, Islamic carpets…but I think the best way to sell you on Campo’s book is really just to quote her! It feels like I’ve never read anything with such force and sensitivity:

What does any examination of man’s condition come down to if not a list—stoical or terrified though the list-maker may be—of his losses? From silence to oxygen, from time to mental equilibrium, from water to modesty, from culture to the kingdom of heaven. And there really isn't much to offset the horrifying catalogues. The whole picture seems to be that of a civilization of loss, unless one dares to call it a civilization of survival, since, in such a postdiluvian condition, dominated by immoderate and universal indigence, a miracle cannot be ruled out: the survival of some islander of the mind still capable of drawing up maps of the sunken continents.

I also keep on returning to this quote:

I love my time because it is the time in which everything is failing, and perhaps precisely for this reason it is truly the time of the fairy tale. And I certainly don't mean by this the era of flying carpets and magic mirrors, which man has destroyed forever in the act of making them, but the era of fugitive beauty, the era of grace and mystery on the verge of disappearance, like the apparitions and arcane signs of the fairy tale: all those things that certain men refuse to give up and love all the more, even as they seem to be increasingly lost and forgotten.

Graphic novels ✦

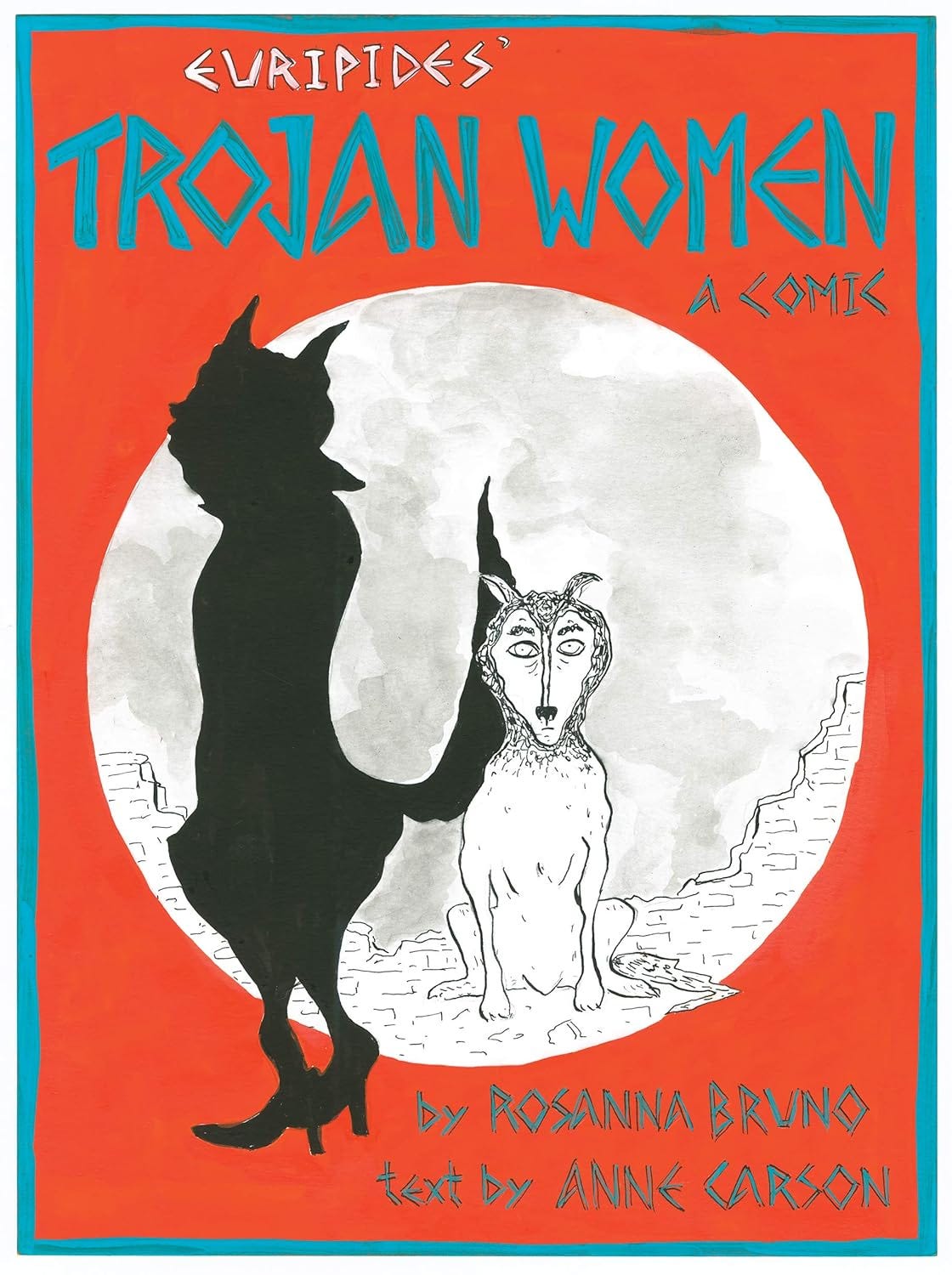

As part of my New Directions subscription, I received a copy of The Trojan Women: A Comic, an adaptation of Euripedes’s famous play. It’s written by Anne Carson (tumblr’s favorite classicist and poet!) and drawn by Rosanna Bruno. The writing style and art style are perfect together—it’s sometimes colloquial, sometimes crude, moving without being mawkish…

Book-length essays ✦

I picked up a gently used (and very cheap, only $2.76!) copy of Leila Guerriero’s A Simple Story: The Last Malambo from Dog Eared Books. It’s an extended essay about Guerrerio’s year-long obsession with the National Malambo Festival. Malambo is an Argentinian folk dance that is tremendously, almost masochistically difficult to perform. Within the malambo community, the national festival is the event of the year. To win is to see your economic circumstances transformed, forever—festival champions are highly sought after (and highly compensated) as tutors. But there’s an interesting ritualistic twist to the festival: once you win the malambo festival, you can never dance the malambo again.

Guerrerio is an exemplary literary journalist, describing the festival contestants in precise and deeply affecting language (translated beautifully from Spanish to English by Frances Riddle). Guerrerio also draws out great quotes from the people she talks to. One of the dancers recalls the advice a schoolteacher once gave him, about choosing a “steady job” versus his true passion:

Are you sure that’s what you want to do?…what you aren’t able to do when you’re young you’ll pass down to your children: failure, frustration.

I also reread Mark Doty’s Still Life with Oysters and Lemon, which is one of my favorite works ever. Doty is a renowned American poet and memoirist, and Still Life is an evocative meditation on how attention to art (Dutch paintings, in particular) and other objects can sustain us in the face of death. The book touches on the last years of Doty’s partner, Wally, who died of AIDS.

The language is beautiful, beautiful, beautiful (I even called a friend and read the first few pages to him on the phone) and seems to inspire beautiful writing from others, too. I love this essay by Martha Park, which uses Doty’s Still Life with Oyster and Lemon to reflect, with remarkable candor, on what it takes to do great work:

Every time I read this…I felt a creeping, ugly envy, not only for Doty’s transformative experience with art, but for his languid inward circling, his language leading steadily inward toward poetic precision. In his patient honing of language, allowing it to do its unfolding, deepening work, I could sense that ingredient so essential to good writing—time—a resource I’d had access to so recently, but could not seem to get back.

I was working a string of meager part-time jobs—teaching writing workshops online, selling buckets of popcorn at a movie theater, tutoring kids at an expensive private school, editing novels and articles for other writers…

Time had become an unseen, muscular force I could sense along the edges of any piece of writing I admired. I knew without making more time to write, I couldn’t do more than jot down what I saw each day—nothing beyond noticing, that bare minimum.

Novels ✦

Just one: Monique Truong’s The Book of Salt, a historical fiction novel about the private chef of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Stein and Toklas lived together at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris, and hosted a salon that various literary and artistic luminaries attended: Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway. They had a Vietnamese chef, and Truong’s novel imagines where this chef came from, what brought him to the household, and what the life of a closeted gay immigrant in 1920s Paris might have been like.

I enjoyed this novel, but it has the kind of descriptive heaviness and seriousness that seems endemic to historical fiction. In Truong’s novel, that heaviness is cut through with humor—the cutting observations of a household servant noticing all the hypocrisies of the bourgeoisie—so it works well, and I’d still recommend it! (Also, who doesn’t want to read Gertrude Stein fanfiction?)

But reading The Book of Salt reminded me why I rarely read historical fiction. I generally prefer a more light, supple, and experimental approach—think Laurent Binet’s HHhH (one of the best books I read in 2023), which is simultaneously a historical fiction novel about two Czechoslovakian men trying to assassinate Hitler’s chief of security, and an autofiction novel about Binet’s struggles when researching and writing it.

Artistic self-help ✦

I read two books that I’d broadly describe as artistic self-help. The first was Steven Pressfield’s Turning Pro. It’s one of those books that feels too embarrassing to recommend. The cover is ugly. The subtitle (Tap Your Inner Power and Create Your Life’s Work) is crudely direct. But the book is incredible.

Pressfield writes about his early life as an “amateur” (which he defines as someone unserious about their practice) and how he committed himself to writing like a professional, years before he saw any success as a writer. Here’s his description of the self-loathing and shame that amateurs often have:

My ambition was to write, but I had buried it…Everything I was doing in my outer life was a consequence and an expression of that terror and that shame…

In the shadow life, we live in denial…We pursue callings that take us nowhere and permit ourselves to be controlled by compulsions that we cannot understand (or are not aware of) and whose outcomes serve only to keep us caged, unconscious, and going nowhere.

The shadow life is the life of the amateur. In the shadow life we pursue false objects and act upon inverted ambitions.

I then read Verlyn Klinkenborg’s Several Short Sentences About Writing, which is that rare book-about-writing that actually teaches you how to write better on a sentence level, with exercises and examples. The first ⅔ of the book focuses on the unyielding, serious labor of writing well, which Klinkenberg defines as taking each sentence seriously:

Your job as a writer is making sentences.

Your other jobs include fixing sentences, killing sentences, and arranging sentences.

If this is the case—making, fixing, killing, arranging—how can your writing possibly flow?

It can’t.

Flow is something the reader experiences, not the writer.

The last third of the book gives examples of great writing (from writers like John McPhee and Joyce Carol Oates) and examples of bad sentences, with clear descriptions of what’s not working. So many books-about-writing are about the psychology and emotions around writing: Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, and Pressfield’s book. While I obviously love this genre of book, it’s nice to read something that actually teach me something about the craft of writing!

And then I read—this is definitely the most embarrassing book on the list—David J. Schwartz’s The Magic of Thinking Big. I’m conflicted about this book. It kind of feels like a manifestation memo for Mad Men-era businessmen, it gives advice on how to outflank unionization efforts at your company, and has some questionable anecdotes about how positive thinking can stave off cancer.

But, like a fool, I read the whole thing anyway…and it’s also a book with some fairly good advice about taking your ambitious seriously, consistently improving your skills, and living with great agency and optimism. Would I recommend it? I don’t know. If you have an embarrassing obsession with self-help books (like me…) and can stomach one that uncritically fetishizes wealth and corporate success, then this is an acceptable example in the genre. You just have to ignore the political context of, like, every other sentence.

Essays

Ben Lerner on reality and simulation ✦✧ Joshua Citarella’s advice for young artists and creatives

Ben Lerner on reality and simulation ✦

The poet and novelist Ben Lerner reviewed the artist Ed Atkin’s Pianowork 2 for the February 8 issue of the NYRB. Ben Lerner is one of my favorite writers, and this review expands beyond Atkins’s video art to think about the nature of intelligence, reality, simulation, and humanity:

If people reliably weep when you play “the saddest of all keys,” then D minor can be used as a kind of CAPTCHA test: if you don’t weep, you might not be a person…

I’ve always thought of artworks as a kind of CAPTCHA test I might not pass. Am I feeling the right things at the right pitch of intensity? What if I’m discovered to be lacking in some fundamental capacity—what if I’m the avatar or replicant? When I watch Pianowork 2 I’m not only moved and discomfited by my sense that Atkins’s digital model might be developing a capacity for pain, but I’m also made to reflect on the rightness or specificity of my own responses.

Joshua Citarella’s advice for young artists and creatives ✦

Earlier this month, the artist and internet culture researcher

shared “A Letter to Young Creatives”. In it, Citarella describes how his artistic practice has been shaped by projects that began as playful, unserious work. Bolding mine:Generally speaking, we can lump our projects into two categories, “the official artwork” and “the stuff we make along the way”. Artistic practice is always filled with interruptions and side quests. Today, I feel rather relaxed about opening an institutional show and instead I’m experiencing a lot of stress about an upcoming podcast with a 16-year-old meme poster. (Not what I might have expected.)

The lesson here is that we often don't know what the important work is while we’re making it…The artworks and essays that are on my syllabus today, in the universities where I teach, are largely things that were considered side projects and not the “official” gallery work. Simply put, we don’t know what is important until many years later.

If you’re solipsistic[al]ly making paintings in the studio, while shitposting with your friends on Discord, you may look back a decade from now and realize that the real work was actually what you were putting online. No artist begins with a fully realized practice. Ideally, we can hone this ability over time. Eventually the side project and the main project will intertwine. But don’t think about the situation you’re in as an interruption. It might just be the work.

Tweets

I know what you’re thinking: does this count as reading? Not really…but this month I came across two Twitter threads that felt genuinely intellectually influential to me.

One is about reading (and why philosophers and scientists should read older works), and one is about writing (and what makes for a banal versus insightful personal essay).

Why philosophers read old works, and why scientists should too ✦

People who are exclusively trained in STEM methodologies and ways of thinking tend to assume that fields progress linearly, and therefore newer research and work is always more useful than older research. This mindset assumes that reading Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is basically irrelevant to a contemporary biologist. When this mindset is applied to philosophy and other humanities disciplines, it leads to people asking: wtf is everyone doing reading works that are a thousand years old? Surely they’re outdated?

I really loved this Twitter thread from @pachabelcanon, which describes why reading older works is essential in philosophy, arts, and the humanities—and why it might be valuable to do the same in STEM, too. Some quotes (bolding mine):

philosophy is not science, and there is no reason to apply the model of progress from science onto philosophy. we have something similar in art: we read and listen to and watch the original works of Proust, Chopin and Bergman

we might talk about technical innovations spreading in the arts, like particular chemical paints, or film techniques, but we do not talk about progress as a whole. this is because each work of art remains a "singularity", and we wouldn't assimilate it to some statistical totality

the reason for my interlude into art is that works of philosophy are rather similar. it's not a good idea to think of works of philosophy, especially those in the canon (Plato, Kant, Heidegger etc) as offering a bunch of basic ideas or insights that we can take up detachedly […]most texts from the canon are ... I would say, "fractally complex". like if you read Kant and you come back with the same information you might get from a Wikipedia summary, ur doing something wrong

[…] my own controversial pov is that we should learn from the humanities in the sciences, and read more original work, because i suspect that working through original works (supplemented with modern textbooks) help to evacuate the sense of scientific problems and solutions

What makes for a good personal essay? ✦

Here’s the thing. I love the essay form, but I’m often suspicious of the personal essay form, as typically practiced online. So many personal essays rely on a highly confessional tone—it can feel a bit like oversharing or traumadumping, tbh?—that just doesn’t hit for me somehow.

But earlier this week I attended a personal essay workshop with Matt Ortile, where he linked a great Twitter thread on what makes personal essays good or bad. Ortile is the former executive editor of Catapult, which published hundreds of incredible personal essays before being shut down—I’m blaming Elizabeth Koch for this one. (What’s the point of being a Koch Industries heiress and creative writing MFA graduate, if not to use your familial wealth to throw money at writers?)

In the Twitter thread, Helen Rosner (the food correspondent for The New Yorker) describes a two-turn structure for the personal essay:

A friend once used the phrase "professional confessional" about people who can't stop writing about themselves despite doing it neither interestingly nor competently, and, well, it's a phrase that's on my mind today

In most good personal essays, the narrative arc is the evolution of the author as an individual, and they should evolve at least twice:

I have an experience, it changes me.

I learn more about the experience and/or about my first change, and that changes me again.

[…] Most of the bad/boring Profesh Confesh essays stop after (1). The writer is passive, reactive: A thing happens to them, it affects their life, the end

[…] (2) is goddamn hard — it requires intense self-reflection and self-criticism. Personal essaying is basically brutal solo therapy! But…(2) is necessary, otherwise it's just Profesh Confesh crap, and fuck that.

Music

February was quite hectic for me—I’ve learned a very painful lesson about how much writing I can do alongside a full-time job! I spent a lot of time writing at home and being exceptionally antisocial, and playing the same 3 mixes on repeat.

One was this mix by Melbourne-based producer and DJ Tangerine. It opens with slow, melodic reverberations and then shifts into a very exuberant, high-BPM place—

—and this CCL mix. I specifically keep on returning to 34:00, where the song “Renegasm” comes in, and the slow, contained langour of the next twenty minutes…

—and then this LOIF mix. My housemates and I threw a housewarming last month and at some point in the evening I discovered that a friend had taken over the Bluetooth speaker in the laundry room and was playing this:

Design

Package design for everyday ingredients ✦✧ An interview with the designers of Migrant Journal ✦✧ Vintage book covers for Guillaime Apollinaire’s poems

Package design for everyday ingredients ✦

The designer and art director

writes weekly posts on the package design for a particular product—mostly foods. Her 14th installment is focused on SALT and includes the much-revered Maldon sea salt.Because I am a woman who loves DECADENCE and CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION, I basically always have Maldon salt on hand. A staple!

An interview with Offshore, the design agency behind Migrant Journal ✦

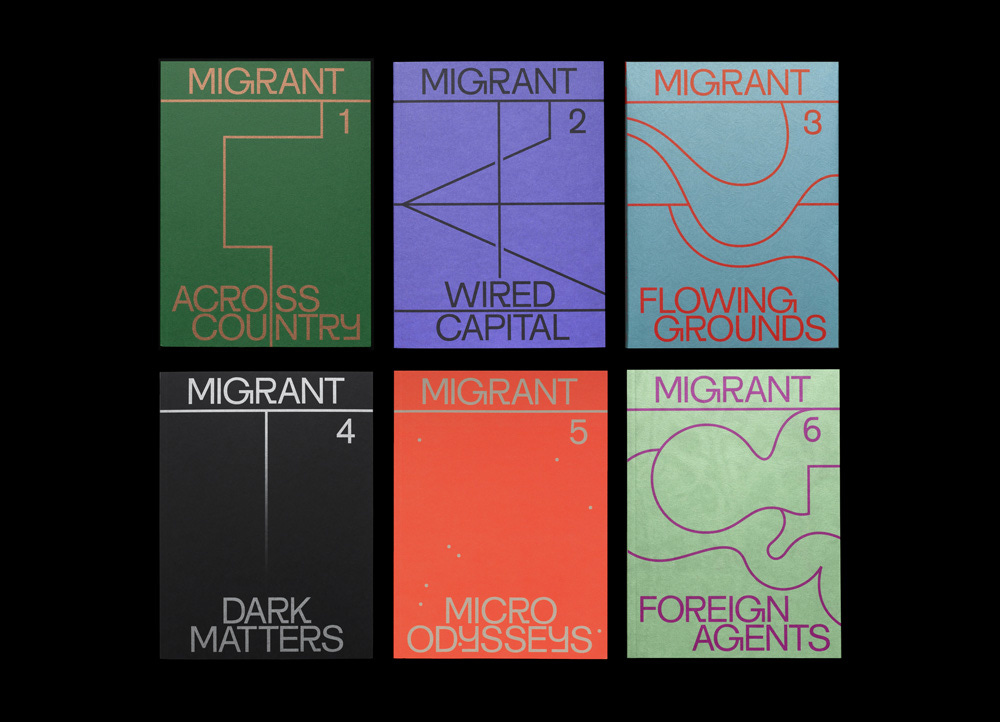

I’ve long admired the graphic design and editorial approach of Migrant Journal, which explores “the circulation of people, goods, information, fauna and flora around the world and the transformative impact they have on space”.

I also admire how they’ve chosen to publish exactly six issues. It’s sad when a good magazine ends, but there’s something to the discipline of deliberately ending a project—not dragging it out, but committing to a fixed set of issues before moving on to other things.

Migrant Journal was published by Offshore (the design practice of Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miler). There’s a nice interview with them on the Harvard GSD’s website, where they touch on their latest project for the GSD and their motivations for publishing a magazine:

The decision to produce a magazine, and not make a website or a book, was purposeful. We strongly believe that printed publications can create a reading experience that lasts longer than most ephemeral bits of information on the internet. As soon as it’s online, it’s lost in the stream of information, and we didn’t want this. Print is still the technology that ages better than any other carrier of information.

I have so much more to say about print books and physical information structures—and how they might, ultimately, be more enduring (and easier to archive and preserve) than digital content. But that might be a topic for another post…

Book covers for Guillaume Apollinaire’s poetry ✦

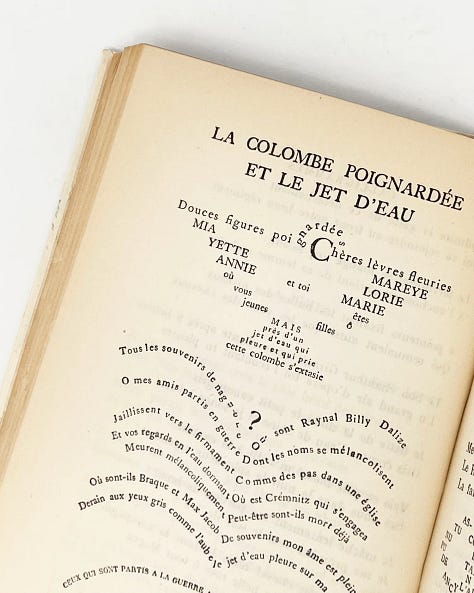

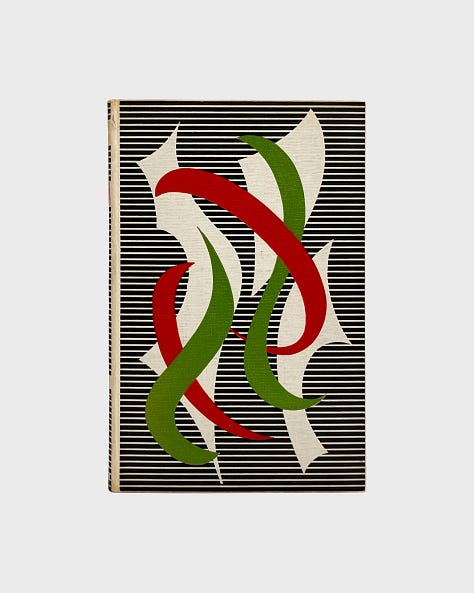

I continue to be obsessed with modernist book cover design—specifically, for the 1945 edition of Guillaume Apollinaire’s Calligrammes (left) and a 1944 edition of Alcools; Poèmes 1898-1913 (right).

Apollinaire was an avant-garde poet who wrote highly visual, typographically exuberant poems. The covers feel so perfectly suited to his style, with bold lines and intersecting, interwoven shapes:

I’ll just close by saying: thank you for reading, emailing, commenting, and generally discussing BOOKS and CULTURE and IDEAS with me! Wishing you all a month full of love, and a spring bright with possibilities. ✦

Love Still Life with Oysters and Lemon endlessly!

11 books in a month is astounding. thanks for sharing your recs!