everything i read in august 2024

what books should you bring on a summer vacation? ✦ and 2 Taiwanese coming-of-age films

On the first day of August, I packed a suitcase and left for an extended summer holiday—2 weddings and 2 music festivals, with long stretches of time in between. Reading on a vacation feels different: I’m spending more time in transit, and I use books to occupy the dull monotony of waiting to board a plane, waiting for the plane to take off, waiting to disembark, waiting for passport control. And once I’ve arrived in a new, attractively unfamiliar city, whatever I experience there—architecture, climate, the energy of the people around me—ends up permeating the text.

But the languid glamour of reading on holiday! has been balanced out by working on 2 writing projects, and having to organize my time around the research, drafting, and editing required. Halfway through August, I came across a tweet that quoted Virginia Woolf’s diary—

—and that kind of anxious, fretful desire to do something, write something has filled up the last 2 weeks of August. When I’m working on a writing project, reading is never really just reading. I’m looking for information, ideas, a technique I can steal. “Whatever book I read,” Woolf wrote in her diary entry, “bubbles up in my mind as part of an article I want to write.”

All things considered, though, August was a lovely combination of leisure and intensive, energetic productivity. Below, brief thoughts on what I enjoyed this month:

5 books (2 nonfiction, 2 novels, and 1 diary)

2 films (a Taiwanese classic, and a recent Taiwanese-American debut)

Essays on art, AI, agriculture, and…intelligence agencies

And some favorite design artifacts (graphic design, textile design, jewelry design)

Books

Reading as vacation activity

There’s something deeply romantic about packing the perfect books for a vacation. But what should those books be? One strategy is to pick a book set in a particular country, or by a writer strongly affiliated with it. In the past, that’s meant bringing Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 to Mexico City (although I didn’t finish the book…I will someday!) and Søren Kierkegaard’s Either/Or to Copenhagen (which I did finish, because my flight there was delayed by several hours, and there was nothing to do on the plane except read).1

The other strategy I use is picking a book that’s thematically relevant to my vacation activities. In 2019, when I was still living in London, I visited Vienna for Christmas and brought Ornament and Crime, a collection of essays by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos. I was very interested in design and architectural history at the time, and most of my trip was spent at MAK (Vienna’s applied arts museum, which regularly exhibits industrial and graphic design artifacts) and walking around the city to see various Loos-designed buildings.

I combined both strategies for my weekend in Barcelona, which was largely planned around going to Parallel, a festival for ambient and techno music. The books I brought:

Javier Marías’s novel The Infatuations (which is set in Madrid, but close enough?), a beautifully engrossing story of a young woman who works at a publishing house and develops a semi-parasocial fascination with a couple that goes to the same café as her. When the husband dies unexpectedly, the woman ends up briefly—but memorably—caught up in the widow’s grief, as well as some unanswered questions about why the husband died. The writing style feels a bit like if Proust wrote a murder mystery—highly interior, lots of reminiscing and energetic mental speculation, even if all that’s happening is the protagonist staring at people on the street and observing social interactions in different people’s homes.

Brian Eno’s 1995 diary A Year with Swollen Appendices, which I’ve been meaning to read since Max Bittker tweeted about all the passages where Eno writes about being addicted to Photoshop and KidPix. Eno is often described as the father of ambient music, so this choice felt very appropriate! The diary is so charming—lots of details about Eno’s work with U2, David Bowie, and Laurie Anderson; dinners he cooked for his 2 youngest daughters; and his enormously wide-ranging and fascinating reading tastes. Also, before reading this diary, I thought the “swollen appendices” in the title were an oblique reference to Eno getting an appendectomy or something—it turns out it refers to the numerous essays appended to the end of his diary. Topics covered: “axis thinking” instead of binary thinking; designing screensavers; when celebrities should/shouldn’t be involved in charity projects; the pros and cons of defense spending as a driver of innovation; the purpose of art (for the artist and for society more broadly); and a list of “unthinkable futures.” It’s funny reading this book in 2024, when some of Eno’s futures have come to pass:

‘News’ is increasingly understood to be a creation of our attention and interests (rather than ‘the truth’), and news shows are redesigned as ‘think-tanks’ where four interesting minds from different disciplines are asked the question ‘So what do YOU think happened today?’…

Big changes in education: a combination of monetarism and liberalism creates a new paradigm wherein schools are expected to be run as successful business, manufacturing and research enterprises…People with lots of money give their children small ‘start-up’ companies for Christmas, or endow their kids’ schools with them.The anthology Chance, edited by Margaret Iverson. It’s from a series published by the MIT Press and Whitechapel Gallery (in London), where each book focuses on a theme relevant to contemporary art. This book was so densely packed with useful information—primarily about John Cage and the Fluxus art movement, with occasional discussions of Dadaism and data—that I found myself annotating (in pencil!) basically every page. Such an amazing book! I read ⅔ of the way through, but didn’t finish it—not because I lost interest, but because I simply couldn’t assimilate and digest that much information. I’ll return to the book when I’ve run out of ideas.

The last 2 books ended up being exceptionally useful for my last post on AI art—thanks to everyone who commented (or emailed me privately) with additional thoughts and reference points!

It was lovely to read A Year of Swollen Appendices and Chance, which both take on questions like: What is art? What is the artist’s role in defining a clear intention for a work, or leaving room for chance and collaboration? How do new technologies shape art?

Reading as research activity

The AI art post ended up being a classic example of research as leisure activity. I started reading about Fluxus and experimental/generative music purely for fun, and ended up accidentally constructing an essay on generative AI and how I think it should (and shouldn’t) be used for artistic production.

It’s always exciting when I write something almost accidentally, without really intending to develop a thesis or argument, but situations like that are rare. My other August writing project was something I’d pitched back in July—a review essay on a recent MIT Press book—and the research process was a little less leisurely and a lot more intentional. As part of my research, I read:

The philosopher (and former L.A. Times food writer) C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art. This was such an immense pleasure to read—Nguyen’s writing is so clear and precise and eloquent, and the book is such an exciting discussion of what counts as “art,” and how to think about different art forms and their distinctive modes of expression. If you’re interested in the book, here’s my brief Goodreads review of it, and a quote I posted on Substack Notes way back in July:

The political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State, which I picked up after C. Thi Nguyen mentioned it in his podcast episode with

. This is more than just an “AI podcast”— is a really excellent interviewer and brings on a wide range of academics and intellectuals to think about technology, culture, and cognition.Seeing Like a State is one of those rare academic monographs that end up developing broad popular appeal. When Scott passed away in July, the New York Times’s obituary noted that his research won fans across the political spectrum, “including the free-market libertarians of the Cato Institute and the lefty theorists of the Occupy Wall Street movement.” It’s also part of the “Silicon Valley canon,” as

noted on Twitter. It was quite helpful, honestly, to have a huge glut of obituaries and essays and posts and tweets discussing Scott’s legacy as I was reading the book—it helped me place his ideas in a broader context. I found ’s post especially helpful:

I’ve wanted to read Nguyen’s Games and Scott’s Seeing Like a State for a long time—I was really happy that this writing project helped me finally get around to it!

I tend to treat each writing project as an container for everything I’m thinking about at the time…and this particular essay is, loosely, a container for the following topics: 20th century computing and design history; videogames as an art form; how to write about software; utopian urbanist projects; how annoying it is that bike lanes, in most American cities, feel so cramped and unsafe. I can’t wait to share it with you all!2

Reading as a way of remembering a city

I’ve spent most of August in London, where I lived for 4 years until moving back to San Francisco. What I remember from that time:

Scrolling through Spareroom ads for warehouses in north London so that I could save money on rent during grad school (I ended up living in a more conventional flatshare instead)

Conversations at a friend’s birthday party about dancing at Dalston Superstore (I’ve never been, but it seemed like the kind of culturally significant destination that everyone gay and queer was supposed to have gone to already)

The exuberant energy in the city during bank holiday weekends

The defensive pride that people had about their accents, especially if they were Irish, from the north, or from the midlands

I loved my time in London! But I never felt like I was fully in, a local—by the time I left, I still felt like an over-eager American who had simply lingered a little longer than most tourists do. But I loved being on the edges of it all. I loved getting to say queue and greengrocer. I loved listening to people complain about their years at CSM. And that feeling of voyeuristically peering into the city, observing the culture from a fascinated, semi-intimate remove, is what it felt like to read Oisín McKenna’s debut novel Evenings and Weekends, which takes place in London.

The novel takes place over a bank holiday weekend in June 2019, and it follows a large cast of characters—mostly young, mostly gay or queer—as they fall in and out of love, keep secrets or confess them to each other, and struggle towards the lives they want. It really does feel set in London—not just incidentally taking place in the city, but completely shaped by it.

And I’m so impressed by how well McKenna handles all the people in the novel—the early chapters switch through 3 characters and their perspectives, but many of the side characters (a young man’s mother, the boyfriend of the guy he’s in love with) end up getting their own chapter too. It’s a bit cliché to talk about how novels can activate or train your sense of empathy, but I really felt that in McKenna’s novel—every character that seems like a minor figure in one person’s life is revealed to have a rich and well-realized inner world, and their own set of anxieties and aspirations.

I heard about the novel, by the way, through McKenna’s conversation with

in Interview Magazine. It’s a really fun and funny interview—and it touches on the class consciousness in Evenings & Weekends as well:

JOHNATHANI would say the book belongs to a new group of writers here in the UK, like Rose Cleary, for example, that’s addressing some quite serious issues of housing and gentrification and the damage it creates across communities.

MCKENNAI didn’t really think that I was setting out to write a book about gentrification and housing. I did think deliberately about the need to earn rent creating limits on people’s capacity for pleasure, and the push and pull of trying to have a rich life in the city while also having to earn money to live in often poor conditions. I guess it’s unavoidable if you’re speaking to the conditions of the world that you’re in.

Films

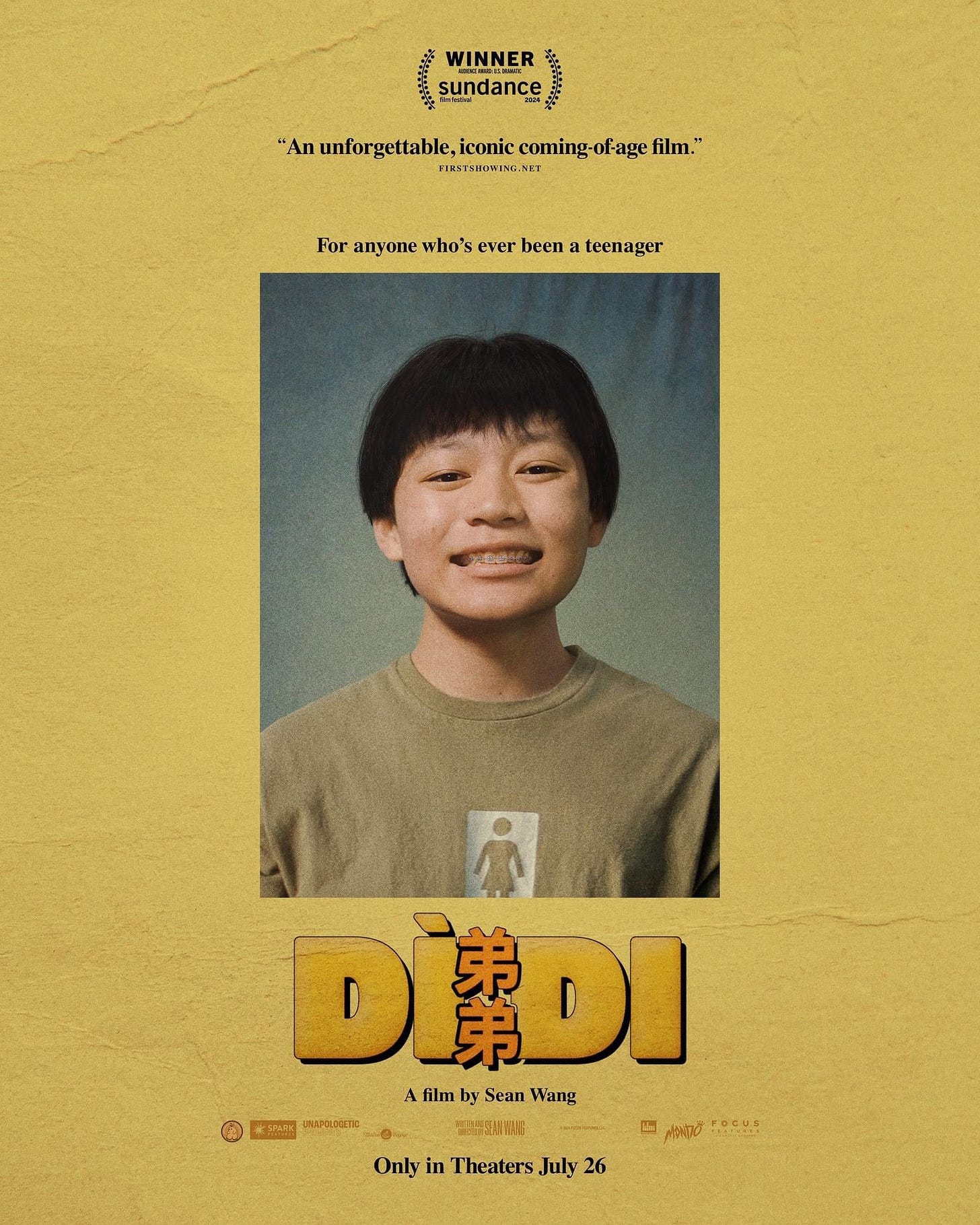

I also watched two films that were remarkably, gloriously, and very satisfyingly set in a place and time. The first was Sean Wang’s Dìdi (2024), a coming-of-age film set in the Bay Area. The film follows a young Taiwanese-American boy, Chris, in the transitional period between middle school and high school—but it’s also about that transitional period between teenagers using MySpace and using Facebook.

One of the earliest scenes shows Chris playing with a Livestrong wristband (remember those?); other scenes show him messaging friends on AIM, scrolling through his crush’s Facebook profile to check if she’s single, and checking an estranged friend’s top 8 on MySpace to see whether he’s still listed there.

Much has been made of the film’s depiction of second-generation Asian-American immigrant families (and it is really genuinely moving in this regard! many of the scenes are set in Wang’s actual childhood home in Fremont, too)…but the thing I’d really like to talk about is how it feels like a time capsule of a very particular moment in software and interface history. I was so impressed by how all these 2008 interfaces were recreated for the film—the instant nostalgia hit watching Chris post on his Facebook feed! It’s so rare to see online interactions depicted well in films (it often feels kitschy and artificial to me), so Dìdi’s approach felt like a revelation. From an IndieWire article about the film:

For “Dìdi,” Wang assembled a team of four animators and graphic artists, working off screenshots, to recreate the now-defunct 2008 internet from scratch. It was a surprisingly painstaking and time-consuming task to bring back to life a world so ubiquitous not that long ago.

“One of my favorite things, when I watch [“Dìdi”] with an audience, is every time you see that first desktop screen,” said Wang. “I can just feel the audience being like, ‘Whoa, OK. I have not seen all of that in so long.’ And then you hear the AIM notifications, and it’s just this dopamine hit. Everyone knows these user interfaces (UIs), but I don’t think they’ve just been shown in this way in this storytelling context”…

“You’ve heard filmmakers say screens aren’t cinematic, and every time you cut to a screen or a phone it just ruins the movie,” said Wang. “But for me, that was one of the things I was most excited by [in making] this movie.”

Wang’s years working at Google Creative Labs helped him use small interactions and gestures to convey Chris’s emotions:

“Our movie’s all about shame, so like, what does ‘delete’ mean, how does that communicate shame? How does a blinking cursor convey butterflies when you’re talking to your crush? I think all of those little things I learned at Google,” said Wang. “The nuances of a blinking cursor, micro mouse movements, deleting stuff and then typing it and deleting it again, that’s his internal monologue. And so it was like, ‘OK, how do we use all these tools for storytelling?’”

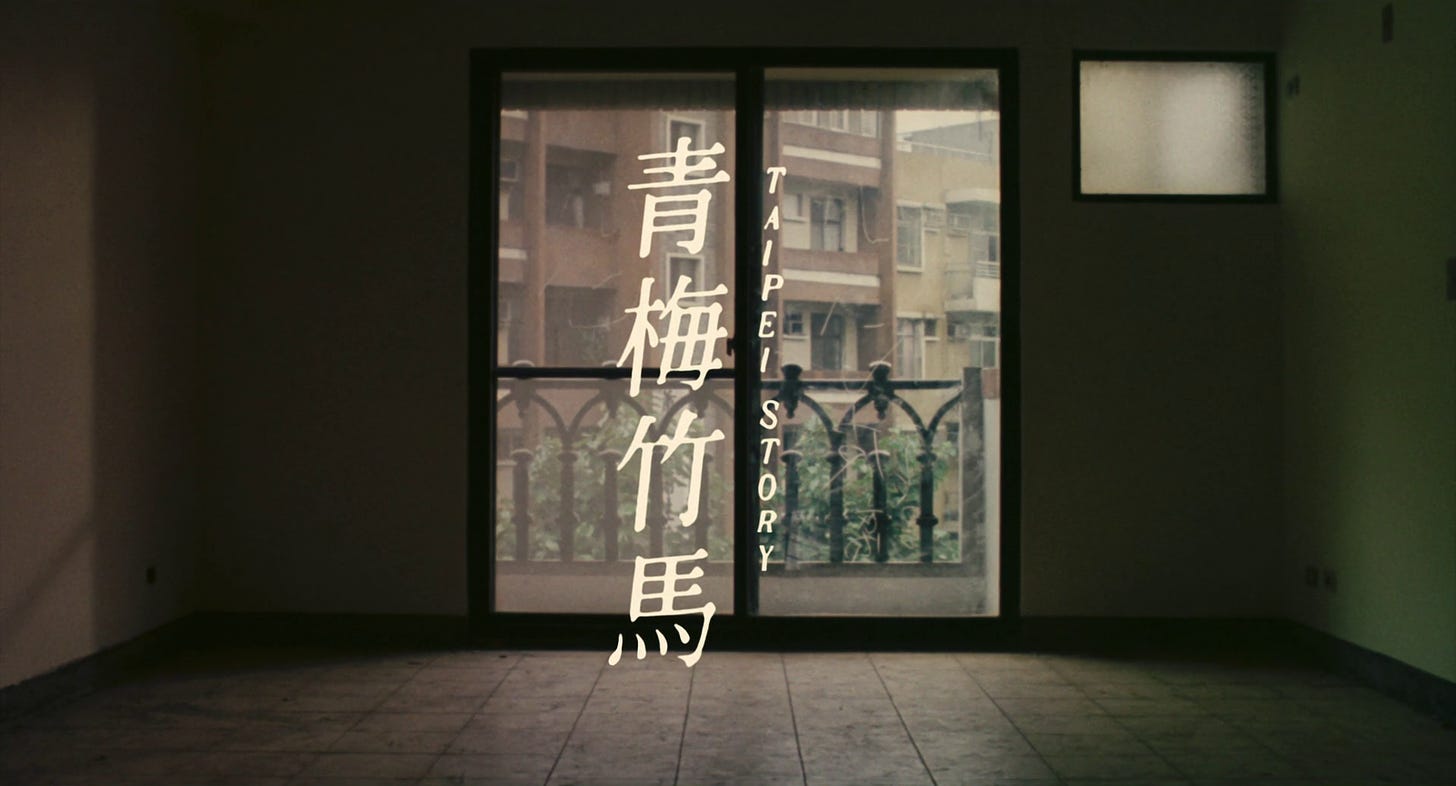

Quite a few of Dìdi’s scenes also felt like an homage to the Taiwanese director Edward Yang’s films. A week after seeing Dìdi, I watched Yang’s Taipei Story (1985) at the ICA.

In Taipei Story, Hou Hsiao-hsien (who cowrote the film and is a great Taiwanese director in his own right) plays Lung, a former Little League member who returns to Taipei after a stint in LA. His childhood sweetheart, Chin, is a proto-girlboss figure whose promising career is cut short when the company she works for is acquired, and her mentor leaves. Chin’s new boss tries to demote her to a mere secretary, so Chin quits—and spends her time lying in bed, reading, journaling, looking extremely stylish in an array of acetate sunglasses, and occasionally calling her mentor to try and get a new job.

I quite liked Andréa Picard’s description of Chin’s character:

Fashionably dressed with a chic hairstyle, and shielded by her dark sunglasses, Chin is a woman of the future, as so many of Yang’s female protagonists are, moving beyond the temporary solace of nostalgia despite the complicated vicissitudes of modern life. The men, however, rarely fare as well.

The film shifts between the strained, disintegrating relationship between Lung and Chen (who both have furtive, alternate love interests); the financial irresponsibility of Chen’s father and Lung’s attempts to bail him out; and other family members and friends all trying to make it work in a rapidly modernizing Taiwan—with some characters clearly winning economically, and others facing a brutal, precarious reality. If you have any extended family drama that involves a patriarch’s gambling addiction, and/or strained relationships between siblings who have moved to the US and siblings remaining in the homeland…well, this is a really great film, but it may be a bit too relatable!

I previously wrote about Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (his seventh and final film!) and how Edward Yang went from working as an electrical engineer in Seattle to becoming one of Taiwan’s most renowned film directors—

Essays

There’s far too much great writing online—and people keep on publishing new work all the time!—but my favorite essays in August focused on 2 topics: AI art, and the genocide in Gaza.

On AI art

In my recent post on AI art, I mentioned that “80% of AI art writing suffers from 1 of 2 problems: The people who understand AI don’t understand (or truly value) art…[and those] who do understand art…in turn, don’t really understand AI—and are deeply fearful of it, hostile, or both.”

One of the rare exceptions to this is the art critic Dean Kissick. In his 2022 column for Spike, “The Downward Spiral: Text-to-Image,” Kissick writes about the kitschiness of AI art—and how to use that kitschiness in novel and exciting ways:

In this age of repetition and mimesis we endlessly remake the past. Even our cutting-edge AIs are trained on the past…The images they make are “kitsch,” according to Clement Greenberg’s definition: derivative examples of low, popular culture that feed off of “the availability close at hand of a fully matured cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions, and perfected self-consciousness kitsch can take advantage of for its own ends.” They are imitations of life. They are imitations, often, of art and its effects. Their beauty, when they are beautiful, comes about by chance rather than purpose. These machines are trained to compose images objectively, so that even styles of expression might be reproduced mechanically and indifferently. Some leading research laboratories are developing the ability to program (imitations of) styles, to appropriate different artists’ styles as materials, and even to combine them. Mannerist artifice is blended with artificial learning. With good written prompts there’s a way, perhaps, I hope, of pushing kitsch so far that it becomes something strange and alluring, even moving.

Kissick mentions a few works he admires—like a DALL-E–generated image by Holly Herndon and Matthew Dryhurst—both musicians and interdisciplinary artists who are constantly experimenting with new technologies. He also mentions the digital artist Ezra Miller as an example of how “AI can be used in subtle ways, to add a wash of unreality to images.”

And Kissick mentions how working with generative AI to create images is particularly exciting for writers:

It’s a uniquely literary approach to image-making. Rather than trying to create images in the minds of your readers, or record sights you’ve seen in words, you attempt to conjure new images in the mind of an AI. You have to learn to describe something that may not exist, and to do so in language that’s tailored for the machine, that it can parse. It’s a radical jump from one form of creativity (writing) to another (computer-generated imagery), and, for a writer such as myself, unusually satisfying and immediate.

Even though it was written 2 years ago, I find Kissick’s essay much more compelling and insightful than Ted Chiang’s recent “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art,” for the New Yorker. The problem isn’t so much Chiang’s critique of AI art’s flaws (especially the concerns about LLMs copying artists and writers in derivative ways), but rather Chiang’s definition of art.

Chiang’s essay, like my own, opens by defining what art is, and what artists are doing when they make art. This is actually a crucial move in writing about AI—because the whole debate around whether AI can create art, and replace artists, only moves forward if the writer and reader can come to some meaningfully shared understanding of what these terms mean.

In his essay, Chiang proposes that

art is something that results from making a lot of choices. This might be easiest to explain if we use fiction writing as an example…to oversimplify, we can imagine that a ten-thousand-word short story requires something on the order of ten thousand choices.

But this accounting of art assumes that an artist or writer has total, autonomous control over every aesthetic and technical move in a piece. And I don’t think that’s true. The literary scholar Jon Repetti, in “Escaping a Hostage Situation,” has a beautifully worded counter to this:

In art, we don’t begin from choice, but from cliché, from a position of determination and dependency. And every actual choice we make in the production of an artwork is achieved by consciously cultivated tactics of resistance to cliché…A radically “chosen” artwork, an artwork that is actually composed entirely of free “choices” made by the artist, is inconceivable. We begin with our given materials, our shared language, our common history, and the overdetermined conditions of our socialization into that history.

While it’s always fraught to make comparisons between human consciousness and AI processes, I’ve often thought of writers as operating in a similar fashion to LLMs. Writers take in an enormous amount of existing language (by reading); they attempt to generate an output that is a response to a particular prompt (an idea they want to elaborate on, a story they want to tell) and context (the cultural moment they’re working within)…and the quality of the input has an enormous impact on the output. As the philosopher Peli Grietzer tweeted, “The actual good question isn't 'is generative AI literature' but 'is literature generative AI' (yes).”

But this isn’t to say that Chiang’s essay is completely misguided. (I should say, also, that I have a huge amount of respect for Chiang. I love his sci-fi short stories, and even recommended them in an article for The Atlantic earlier this year…and his 2023 essay, “Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey?,” is very good.)

As

notes in “Even if AI makes art, it may be bad for culture,” Chiang’s essay raises a number of significant concerns about how AI will affect artistic and literary production. Right now,The outputs of LLMs and other Large Models are, on the whole, blander and less interesting than human created art. As Alison Gopnik argues, they are very strong on imitation, but not on innovation. Even if you think that AI, or much simpler algorithms for that matter, can be used to generate art, you can still worry that the currently popular versions are going to make culture duller and more disconnected.

Farrell then quotes some of Brian Eno’s thoughts on variety and generativity in art to argue that LLMs do not, for now, produce enough variety to be interesting:

Many of the current criticisms of LLMs emphasize their tendency to “hallucinate” or make errors. From an Eno-esque perspective, the problem may be that they don’t make the right kinds of errors. Their imperfections tend to be repetitive, rather than to point towards interesting new possibilities. This is not to say that they cannot be used to create such possibilities, but that their central tendency is towards the easy creation of conformity rather than the generation of variety.

And I agree! Although I’m more optimistic about generative AI than Farrell and Chiang, I still think that much of the art created with Midjourney, DALL-E, &c right now is just…bad. It’s boring. Where is the better art? Is it even possible to push against the innate tendency of LLMs to be repetitive and average—and actually create something novel?

On Palestine

Two exceptionally good articles about the ongoing crisis in Gaza—the first is about civilian starvation; the second is on gay and queer Palestinians who are being targeted by intelligence services.

Mira Matter’s “Stone and Seed” discusses how the intentional starvation of a population, through state actions that destroy the agricultural capacity of a community and force them to be reliant on external aid, has been used as a tactic of oppression. It’s happening now in Gaza; it also happened during the Vietnam War with America’s use of Agent Orange:

As the historian Jessica Whyte has extensively documented, the prohibition on using starvation as a method of warfare was not codified until 1977.

In the preceding decade, Whyte details, the US had used Agent Orange and other chemical defoliants in Vietnam, arguing that crops were shielding Vietnamese combatants and therefore that destroying them was a legitimate tactic, even if such destruction also meant the destruction of resources necessary for life. As a result, it was in their interest to ensure the prohibition on starvation could be interpreted in such a way as to allow ‘comprehensive starvation sieges’ to remain legal so long as they targeted combatants, not civilians.

This ostensible distinction between the active – and therefore punishable – ‘combatant’ and the passive – and therefore innocent – ‘civilian’ has been exploited time and time again.

I really admire Matter’s essay (and

’s commitment to publishing work like this!) because it shows how food writing can take on topics of genocide, humanitarian law, and historical/ongoing injustice—in a very specific and well-researched way.- ’s “How Israel's Elite Intelligence Unit Targets Queer Palestinians in the West Bank” is an incredible work of investigative journalism that discusses how an Israeli intelligence service is targeting gay Palestinians and pressuring them to collaborate—or be outed to their families.

In July, I met with a former high-ranking officer with Unit 8200, the Israeli intelligence service that primarily intercepts communications and monitors the whereabouts of persons of interest. Among Israelis, there is a “bubble of secrecy” that sustains the idea of Unit 8200 as only a defensive agency that targets terrorists, he said. In reality, it has a substantial role in cultivating informants across the West Bank…

The former official said he and his colleagues were instructed to watch for Arabic words like “gay” and “affair” when monitoring communications of potential targets. “You write someone on Facebook or another application to create some connection. At first it has to look innocuous, so you start small, you start with something totally benign, and then you gradually kind of reach more and more and create a stronger relationship,” he said. “You also might bring up in some way or another that you know this person is gay. You don't have to threaten to create an explicit threat”…

“Israelis think we're targeting bad people—we're targeting terrorists—people who are violent, and that's also true,” the former Unit 8200 official said. “But if you want a second circle and third circle and a fourth circle, then anybody's a target. And if you can blackmail cooperation, then you want to try to assemble as much filth as possible.”In the last few decades, it’s been common for people to frame Israel as a beacon of LGBTQ progressivism in an otherwise homophobic region. But Chatelle’s article, to me, highlights how the Israeli state’s efforts in monitoring, controlling, displacing, and killing Palestinians supersedes any warm, fuzzy feelings the state might have towards gay and queer people. How many of the children already killed in Gaza were young gays and lesbians? How many of them have been denied a normal, dignified life—as people, gay or straight—because of Israel’s actions in Gaza?

It’s hard to not feel exceptionally helpless about what’s happening in Gaza now. I’ve taken solace in small actions that feel personally and interpersonally significant. Earlier in August, my friends and I hosted an informal coffee shop/café/closet sale/book sale in London. Thanks to everyone who saw my note on Substack about it and came by!

We raised £400ish for Medical Aid for Palestinians, and if you weren’t able to stop by, please consider donating directly!3

And for San Francisco residents—the novelist

helped bring a very important fundraiser to my attention. Lamea Abuelrous is the owner of Temo’s, a really lovely café in the Mission, and is raising funds to help her family evacuate Gaza. You can read more about Abuelrous and the community that came together to support here here.Four recent favorites

Magazine covers from the 1960s ✦✧ Book covers by Tom Etherington ✦✧ Kitchen textiles by KJP Studio ✦✧ A beautiful necklace

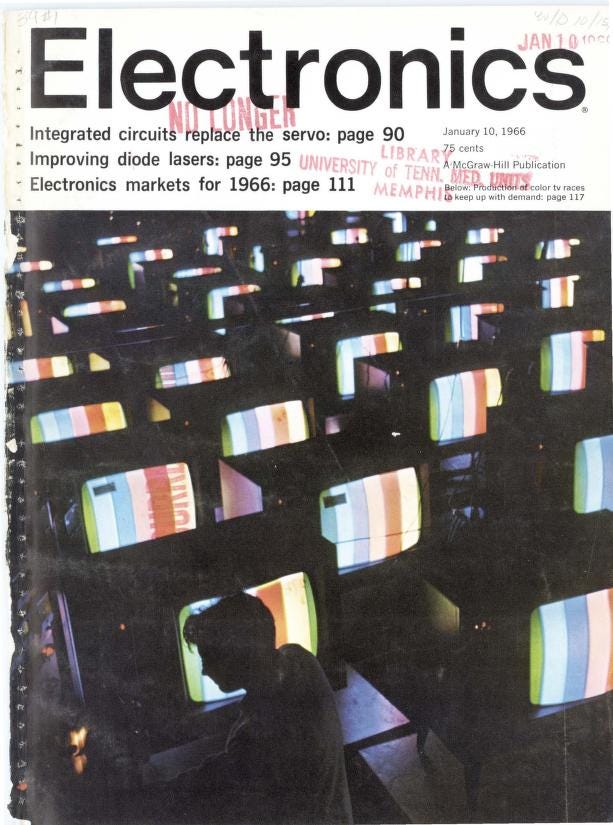

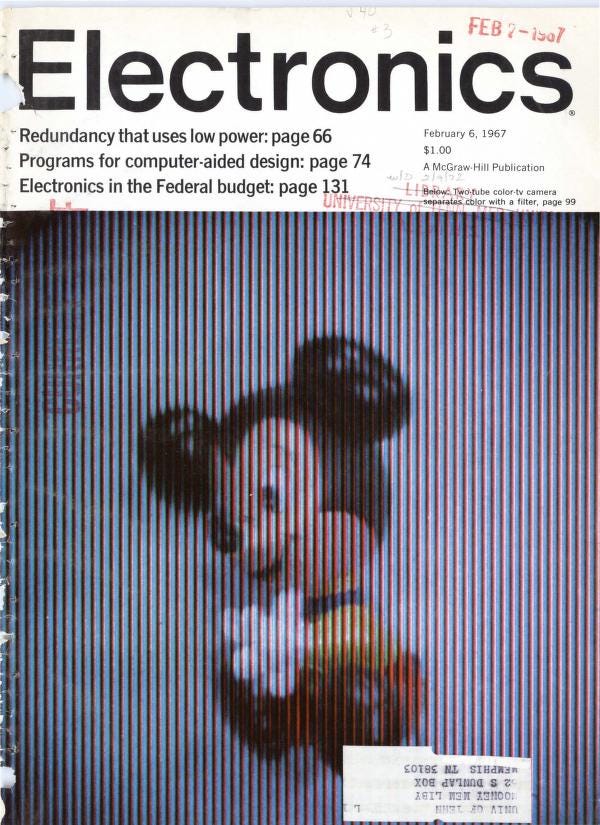

Magazine covers from the 1960s ✦

Thanks to Twitter, I discovered that the Internet Archive has scanned a number of Electronics magazine covers from the 1960s—I love the spare, restrained typography and the beautiful imagery. Two of my favorites:

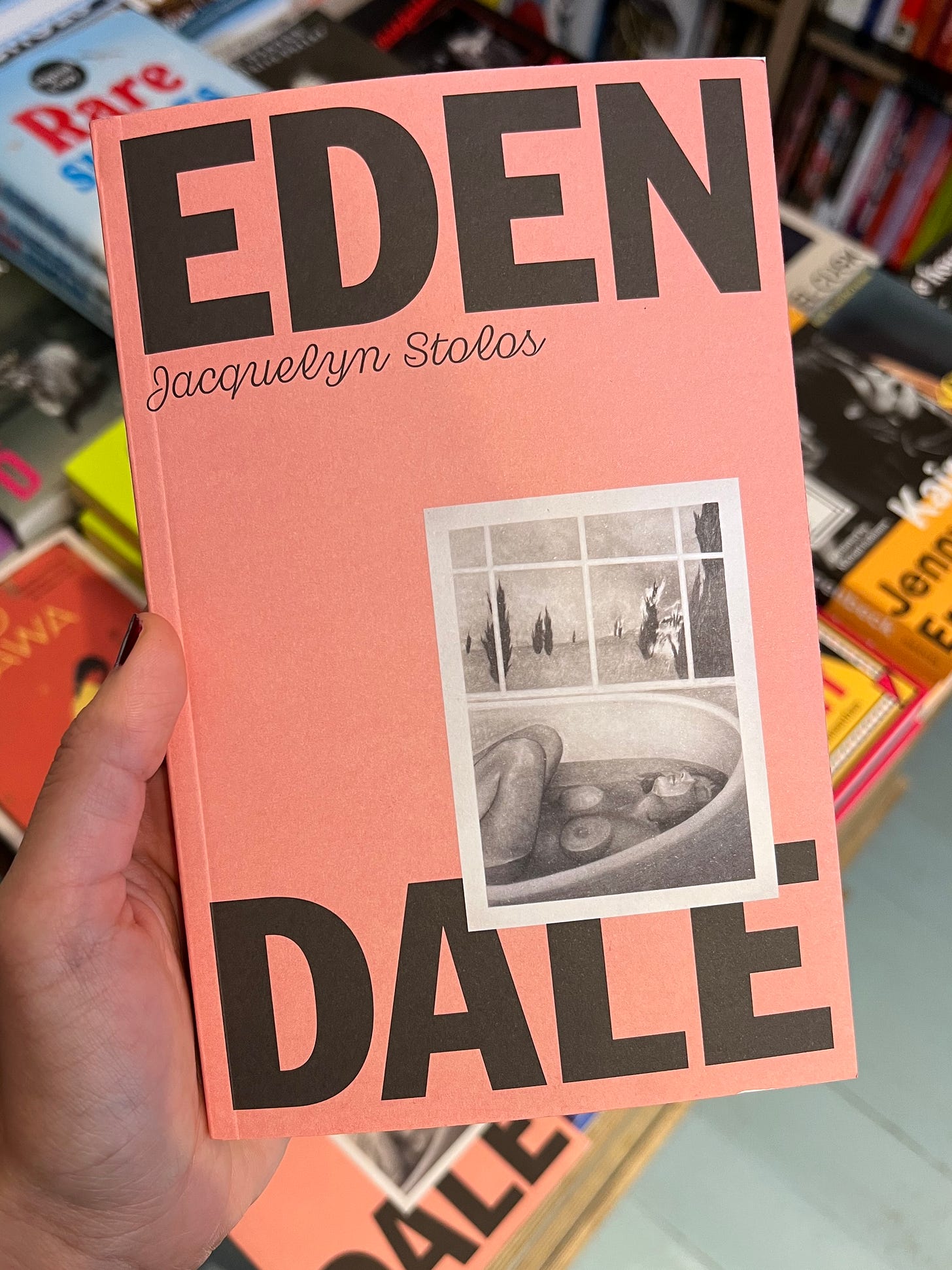

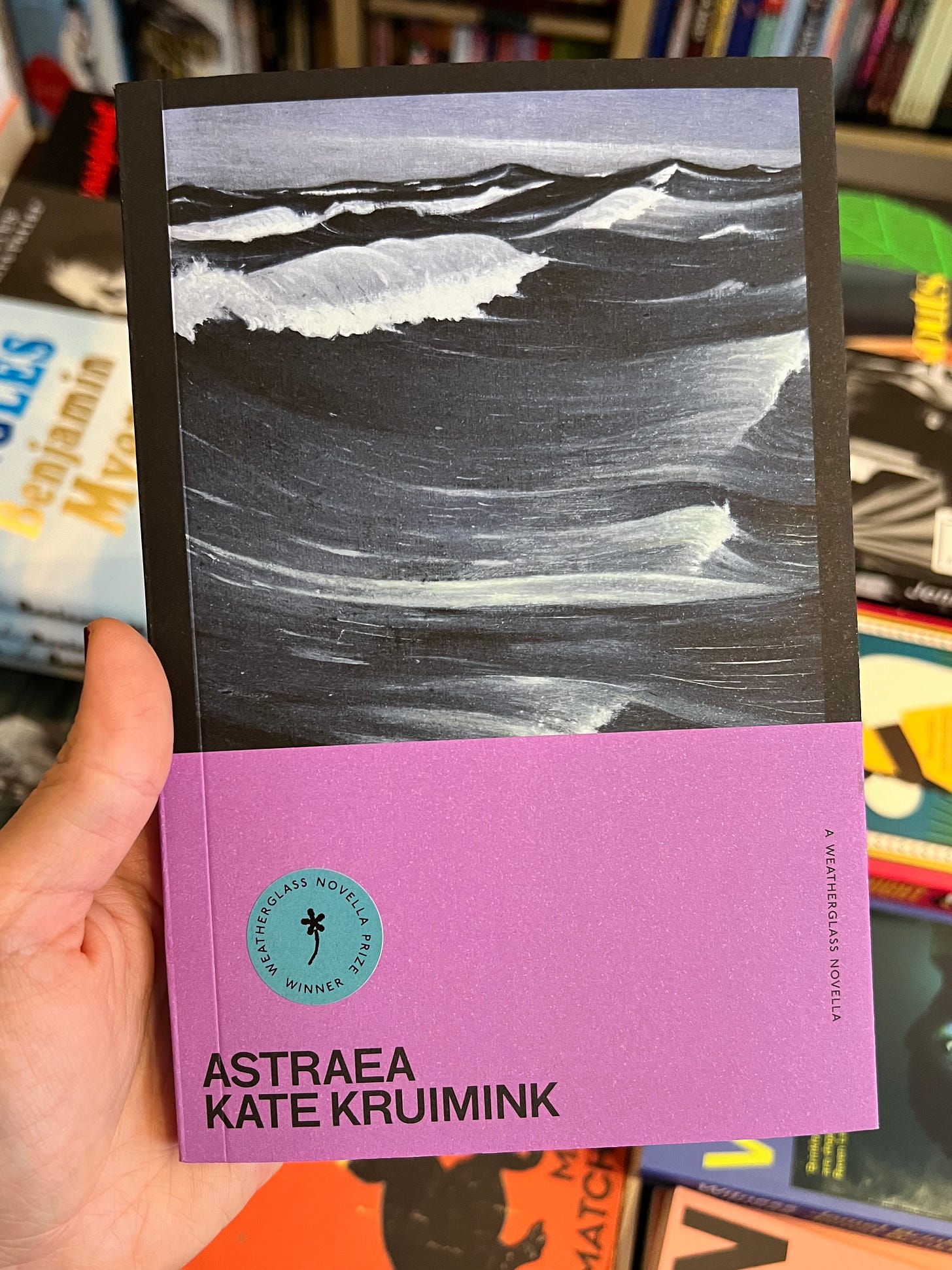

Book covers by Tom Etherington ✦

While in London, I kept on picking up beautiful book covers and realizing they were all designed by Tom Etherington. (

subscribers may also know him as the designer of the sustainable fashion brand Story Mfg’s logo.)Here are two of my favorites (from a visit to Pages of Hackney)—

Kitchen textiles by KJP Studio ✦

My love language is scouring the internet for charming/strange/exciting home goods—always useful as gifts! When it comes to home textiles, I really love the work of Katherine Jean Plumb, aka KJP, and her new linen napkins and dish towels are especially cute.

A beautiful necklace ✦

And on the jewelry design front—I came across La Mar’s work recently, and I really love this oversized, elongated chain-like necklace with little seashell shapes:

I’m always fond of designers who continually return to the same motif and push it as far as possible—here’s another shell-and-chain jewelry piece, and one that could be used as a thin silver belt.

Thank you for reading! If you went on vacation this summer, I’d love to hear about your vacation reading approach (do you bring books at all? are they serious books, escapist books, or both?).

And if you know someone who might enjoy this post, consider sharing it:

Kierkegaard’s Either/Or is one of my favorite philosophical texts for literary inspiration and ethical inspiration. The whole book is structured around a fun little fictional conceit: A man named Victor Eremita buys an expensive desk, after discovering it at an antique shop and longingly thinking about it for days. After bringing the desk home, he discovers two sets of papers in the drawers. Part 1 of Either/Or is the first set of papers, written by an unnamed man whose life is totally oriented around aesthetic concerns; part 2 is the second set, written by a man named Judge Vilhem, who is totally oriented around ethical concerns.

Part 1 is more fun (the aesthetically-driven man clearly enjoys exploring different writing styles and forms) and I recommend it to anyone who’s interested in experimental writing! But part 2 is a very, very moving discussion of what ethical obligations you might have towards your own self-actualizing, towards a wife and family, and towards God. Kierkegaard was obviously very Christian. I do like reading these very religious writers, although I myself am a godless heathen [Buddhist]…

In an unspecified number of weeks. I’m actually procrastinating on edits by writing this Substack post…and this post is late (I normally publish these reading roundups on the last day of each month!) because I was working on the review essay…

When I was younger, I used to find fundraisers like this a bit…misguided, perhaps? Because the money raised seemed so little for the effort involved—why not have everyone donate directly, why go through all the trouble to create an elaborate event and “sell” goods in exchange for donations? If people want to donate, shouldn’t they just do so without an incentive?

The attitude I have now, though, is that the point of a fundraiser isn’t just to raise funds. It’s also an exercise in creating and sustaining community, and being able to meet and spend time with and become closer to people who care about the same things you do. Obviously it was really good and useful that we actually raised money for Medical Aid for Palestinians—but it was also a really lovely way to meet people and have friends over for a few hours. Again: Thank you to everyone who came—and I’m hoping a ceasefire will happen sooner rather than later.

I read more in my 1.5 weeks of travel than I did in months. I'm trying to keep up that habit back home now, mainly by spending less time on the internet. And yes, I'm aware I'm saying this as I'm commenting on Substack lol. But that's a little different!

I agree! I also used to find fundraisers to be silly and self-aggrandizing, but after having seen how the Ruby's fundraiser for Lamea created so much more community support and publicity, I'm like hmm...maybe there is something to the public-ness of the gesture!