encounters with the everyday

baby's first lit crit piece ✦ the critique of everyday life ✦ devotion and Jesse Darling ✦ an incomplete list of my favourite living writers

Earlier this year I became obsessed with the novel Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai. Kanai is a Japanese novelist, poet, and critic.1 She’s highly regarded in Japan, but up until this year—when Polly Barton’s translation of Mild Vertigo was published—there was hardly anything available in English. None of her film criticism or photography criticism. None of her novels. I don’t read Japanese. So I was very excited and grateful for Barton’s translation.

And I read it, and I loved it—which doesn’t mean it was a happy read, or that it was a wholly pleasant read, just that it unsettled me, and moved me, and has stayed with me. I wrote a review for the Cleveland Review of Books—my first piece of literary criticism!—because I wanted to understand what drew me to it. The novel is about a housewife named Natsumi who lives with her husband and two young sons in Tokyo. It’s about grocery shopping, doing the laundry, cooking dinner, meeting friends for dinner, and feeling a certain ambient level of existential anguish. You know! The usual concerns of contemporary life. And it is also (and here I’ll quote from my own review—is that egocentric of me?)—

a novel where commodities are paramount in people’s lives, where brand names hold an undeniable allure. A restaurant is described as a place where “at any given time two people there will be wearing Issey Miyake's Pleats Please.” Natsumi’s grocery shopping lists are written on “Muji A6 paper.” These objects quietly furnish scenes where Natsumi cares for her husband and two sons, does the laundry, washes the dishes, makes small talk with neighbors. Taken out of context, these details might indicate a novel that is insubstantial, uncritical in its fetishization of capitalistic desires. But what they reflect instead is the deadening quality of Natsumi’s domestic life, with its excess of materiality and lack of meaningful activity.

When I finished the review I thought—well. That’s done. A beautiful novel, a novel that finally pushed me to read Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida (Kanai is a huge Barthes fan), but now I’m done thinking about it, surely? Now I can move on.

But I’m still thinking about the central character, Natsumi; about the deadened, constrained contours of her life, and the domestic despair that she can name but not escape from. The novel has stayed alive in my mind—because it shows how, from the smallest everyday objects and interactions, the great existential questions of our lives emerge.

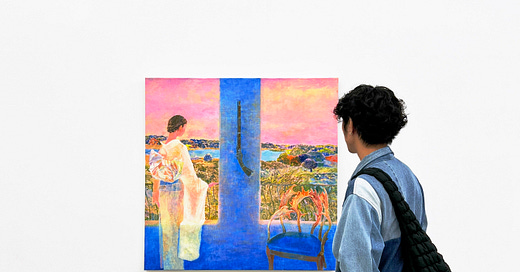

Last weekend I visited Et al. in San Francisco’s Mission district. It’s a bookstore and a gallery and it might be my favourite place in San Francisco right now (with apologies to Dog Eared Books…and City Lights…) because it has an amazing painting show on now, of Minami Kobayashi’s work—

—and because it had a used copy of a book I’ve been wanting for ages!!!!!!!!!!!!!

The book is The Everyday, and it’s part of the Documents of Contemporary Art series. The series is a MIT Press x Whitechapel Gallery collaboration (well, they’re calling it an “editorial alliance”) to publish edited collections that focus on particular themes in contemporary art. There are 52 books in the series, and the titles range from agreeably humble terms (Colour, Walking, Dance, Work) to theoretically imposing shibboleths (The Archive, The Sublime, The Market).2

This particular book came about because, in the editor Stephen Johnstone’s words, “Contemporary art is saturated with references to the everyday…normally unnoticed, trivial and repetitive actions comprising the common ground of daily life.” Maybe it’s because I’d spent so much time this summer with Kanai’s Mild Vertigo; or maybe it’s because, as a designer (and design historian), I am already committed to the centrality of daily life, of its aesthetic and intellectual importance—in any case, I bought the book and started reading it that night.

978-0-85488-159-8The book is elegantly typeset (though with a slab serif typeface, for headings, that feels very 2000s). The selected texts are good. They’re theoretically intriguing and intellectually activating. Some of them are so relevant to Mild Vertigo that I’m almost upset I didn’t come across this book earlier.

For example, there’s an excerpt from the French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life (translated from the French by John Moore). Lefebvre is one of those people that always activates a vague sense of guilt, because I’m always thinking, oh, this guy again, I should really read him, everyone seems to be talking about him…but I still haven’t, of course. But reading 9 pages out of the 944 pages of the entire Critique seems more than good enough.

In the excerpt, Lefebvre writes about the French housewife:

The housewife is immersed in everyday life, submerged, swallowed up; she never escapes from it, except on the plane of reality (dreams: fortune tellers, horoscopes, the romantic press, anecdotes and ceremonies on television, etc)…For the housewife the question is whether she can come to the surface and stay there.

And that really is what happens to Natsumi—submerged by the repetitive rituals of domestic labour, which she escapes only by dissociating on the train, detaching herself from her life. Later on in The Everyday is another excerpt from the French literary scholar Kristin Ross, who notes that one lasting idea from Lefebvre’s work, as well as other work from 1960s French theorists, is that

women ‘undergo’ the everyday – its humiliations and tediums as well as its pleasures – more than men. The housewife…is mired in the quotidian; she cannot escape it.

Perhaps that’s why everyone’s favourite French girl, Annie Ernaux, has such a fascination with grocery stores, supermarkets, shopping malls. The pleasures of shopping. The despair of finding yourself enthralled and in thrall to consumer objects.

And of course this is what happens to Natsumi in Mild Vertigo. She undergoes the everyday, and we are there with her. We see the joy and the suffering inherent in ordinary existence, the desire to escape, the inability to.

All this to say: it’s always special when a new book reminds me so strongly of another book from my past (even if it’s the very recent past). And writing about these two books together—Mild Vertigo the novel, The Everyday as an anthology—makes me realize that I’m not done thinking about the everyday, the ordinary, the humble. And I’m realizing how much I love literature (and art, and design, and architecture…) that insists that the everyday is where our lives are lived, where we learn who we are, where we pass the time and pass from one psychological state to another, sometimes swiftly, sometimes slowly. Sometimes suspended in eternity. Another French philosopher quoted in The Everyday, Maurice Blanchot, declared that “The everyday is our portion of eternity.”

Five recent favourites

Art by Jessie Darling ✦✧ Essays by Francis Whorrall-Campbell, Deborah Eisenberg ✦✧ Film by Sofia Coppola (the girl’s girl of directors)

This year’s Turner Prize winner ✦

Jessie Darling is this year’s winner of the Turner Prize!!!!!!!!!!!!! And this is exciting to me because last year, when I was still living in London, I went to Darling’s “No Medals No Ribbons” solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford.

It was my first time in Oxford. It really is as Oxbridge-y and British as I thought it would be. But instead of going Caroline Calloway on you, I will actually discuss the art—and the kind of fragile, improvisational, endearing quality of many of Darling’s works. The improvisational quality seems to come from the decidedly ordinary, everyday materials. In an interview with the curator, Darling was asked:

ABHow do you choose the materials you work with?JDThe honest answer is that for most of my practice I just used what was cheap or free and easy to find. There’s poetry in objects that everyone is able to recognise from their daily lives, like a shortcut to meaning. I find myself drawn ambivalently to petrochemical materials – steel and plastic, silicone. Plastic in particular is a zombie medium – bright, lurid, doesn’t really decay – and it’s made from fossil fuels, which in a certain sense can be seen as the exhumation of the ancestors. Steel is a technology of coloniality and capitalism – industry, war. These materials have produced my body, in a manner of speaking, and they tell their own stories.

The day I visited Darling’s exhibition was also the day I met the artist and writer Francis Whorrall-Campbell, who reviewed the exhibition for e-flux. It’s always nice to read a review that returns me to the experience of being in the exhibition, encountering the work—but maybe with greater attention, a sharpened sensitivity to the materials and forms and constructions and objects and all the symbolic and affective meaning they bring with them:

“No Medals No Ribbons” is anti-hagiographic…objects from Darling’s practice are recontextualized through different installation or other adaptations. Many of these are also leitmotifs of art history: consider the votive cabinets and tin-foil saints in the final two rooms, Catholic classics alongside a forcibly feminized Batman. The compulsion to repeat across history, whether personal or (inter)national, finally yields different results, even if these are just the hallucinations of a paranoid society. Compulsions and hallucinations are also a symptom of devotion, but what are we madly in love with now that God is out of the picture? With art? With destruction? With each other?

Criticism as fan fiction ✦

A few weeks ago, Whorrall-Campbell wrote an intriguing and provocative essay titled “Criticism as Fan Fiction” for Texte Zur Kunst. The essay discusses a work of Gossip Girl fan fiction that is also about trans identity, and also about affect theory, and has Lauren Berlant as a character—a strange and therefore alluring combination! But it’s also a tremendously insightful discussion of what unites the fan fiction writer and the critic:

[B]oth fan fiction and criticism take as their starting point already existing and complete works of art. Neither are produced ex nihilo but in dialogue with another cultural creation. Second: this desire to respond also marks a certain libidinal investment in the original object. While the emotional valence of this attachment might be differently expressed, the orientation is clear – obsessive even – to an outside observer.

It makes me want to write more criticism. And maybe more fan fiction. But of what? What do I have that investment in, that obsessive orientation towards?

Literary criticism from one of my favourite living writers ✦

In the November 2 issue of the New York Review of Books—which I am only reading now, in December—is an essay by Deborah Eisenberg, one of my favourite living writers.3 In “Virtuosos of Self-Deception,” Eisenberg reviews the Italian novelist Elsa Morante’s Lies and Sorcery, which is about a young woman named Elisa who is orphaned twice—first when her parents die, and again when the woman who raised her (a sex worker named Rosaria) passes away. This is where the novel begins.

The essay has everything I love about great literary criticism. It is accessible without condescending to the reader.4 It is interesting even if you haven’t heard of the novel. It is interesting even if you have no intention of reading the novel. Because when Eisenberg explains who Elisa is, and what problem she faces, she does so like this:

In the silence of her sudden solitude, she sees that she has lived her life in thrall not only to the lies her parents lived by but also to the progeny of those lies: insubstantial, self-flattering, childish, and consuming fantasies of her own construction.

These consolatory and pleasurable fantasies—fantasies of a prestigious (even solvent) ancestry and loving family—have insulated her from painful realities, but only at the cost of leaving her disastrously diminished, arrested, isolated, and all but immobilized. Clearly, she must find her way out of this self-perpetuating prison by disentangling herself from the skeins of deceptions she has inherited and elaborated. “All I desire is to be honest with myself,” she says. But how is she to go about that, debilitated as she is? It takes a great deal of energy and all too much practice to be a person—to yield to reality as it comes at you.

You don’t have to read the novel, nor be invested in the characters within it, to feel moved by this. Because who among us hasn’t lived with “insubstantial, self-flattering, childish, and consuming fantasies” of the self? Who hasn’t found themselves in a “self-perpetuating prison”, “inherited” from the people and culture that raised us, and then “elaborated” by our own inclinations towards ignorance, mystification, and delusion?

This is what therapy is for, I suppose—therapy, psychoanalysis, and literature. And this is really what Eisenberg’s own fiction, across 5 short story collections, is intensely concerned with. How we live with ourselves. How we face ourselves, our failures, our weaknesses, our inadequacies. How we learn to take our lives seriously.

Day in the life ✦

Since I’m already writing about Eisenberg, I might as well bring up the short story “Days”, which appears in her first short story collection, Transactions in a Foreign Currency (1986). I love, love, love this story. To me it is perfect, sublime, an ideal representation of what it means to be twenty-something and quietly panicked about your life and afraid that everything about you is unbearably, unremittingly inadequate, that you’ll never become anyone interesting, that you’ll never be able to sit still with yourself, that you’ll never attain some measure of self-assurance and serenity.

It is about a young woman who quits smoking and takes up swimming at the Y instead. She is lonely, self-conscious, unable to regulate her emotions—but she also fundamentally inquisitive, curious about others, and capable of forcing herself to interact with the world. And in a very quiet, ordinary—one might even say everyday—way, she comes to terms with herself, begins to trust in her own resilience.

In an interview with the Paris Review, Eisenberg reflects:

“Days” is…by far the most autobiographical piece of fiction I’ve ever written. I avoid using real people, including myself, in my fiction, but that piece started out as nonfiction—an account of going to the local YMCA…as a way to endure the horrible ordeal of stopping smoking.

I had had no idea how deep the addiction went—it had essentially replaced me. I was a human being who had structured herself around the narcotic and the prop, who had melded with the narcotic and the prop. Once the narcotic and prop were no longer available, the human being simply died. I was left in a kind of mourning. I was grief stricken. I had murdered someone, and it was me. But as it turned out, that was the only way to allow a less restricted human being to take shape and live.

Lost in Translation ✦

This year I’ve been telling everyone that I’m film illiterate. By this I mean: I haven’t seen, like, anything that a vaguely culturally oriented young person is “supposed” to have seen. But I am addressing this character flaw, I promise! And most recently I addressed it by finally watching Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. Here’s my quick, punchy, Letterboxd-style review: they spend 50% of the film at the Park Hyatt Tokyo bar, and 50% of the film showing off a really great soundtrack.

For the past few weeks I’ve been commuting to work and listening to “Alone in Kyoto” by Air. The opening has such a shimmering, delicate quality to it—it feels saturated with some indistinct sentimentality, and listening it makes me want to fall in love and break my heart and book a flight to Japan and overpay for the crudités at the Park Hyatt Tokyo bar.

The 2000s! Electronic music in the 2000s! They really understood how to make you feel lovesick over absolutely nothing. As did Sofia Coppola, of course.

I would ordinarily collapse this into merely “writer”, but the more novels and poetry and criticism and essays I read, the more humbled I am by how hard it is to be good, really good, at just one form. Never mind multiple forms. Never mind the intersection between multiple forms. Mild Vertigo fascinates me because it’s a novel; it also contains photography criticism (if you’re a Nobuyoshi Araki fan, prepare to feel attacked); and supposedly this woman writes poetry too??

Some of the Documents of Contemporary Art titles might be juxtaposed in an appealing and intriguing way: Work/Boredom, Craft/Destruction, Documentary/Science Fiction, The Object/Abstraction. A combo gift idea for the amateur art theorist in your life? Or me…

The inevitable question: Who are your other favourite living writers? I’m being put on the spot (by an imagined interlocutor); I hesitate; I’m self-conscious. But of course I have an instinct for who should be on the list—Lydia Davis (fiction, translations), Sarah Schulman (nonfiction), Andrea Long Chu (essays, criticism), Claire-Louise Bennett (fiction), Olga Ravn (fiction). It’s an incomplete list, because I keep on reading, and I’m convinced that each new book I read is what will introduce me to yet another favourite.

Oh, I have so much to say about accessible writing that doesn’t alienate the reader through a clearly evident condescension—but for now I’ll just link to Becca Rothfeld’s essay for The Yale Review, where she asks: “Why do public intellectuals condescend to their readers?”

Hi Celine, there is an earlier translation of Kanai's earlier works, Indian Summer: A Novel. It was released in September 30, 2012. I think you'll like this novel too. It focuses on the interiority of womanhood, women, and their everyday lives.

Celine! I recommend you read Rita Felski's essay 'The Invention of Everyday Life' from her book Doing Time. She gives a really nice definition of everydayness and problematises Lefebvre, Blanchot, de Certeau et al. a little.