edward yang's yi yi and the tender despairs of taiwanese family life

the tech worker turned Taiwanese New Wave filmmaker ✦ my anti-algorithmic year of cultural consumption

The concept of a canon—a culturally sanctioned set of works, mostly older or “classic” in some way, and essential to one’s education as a cultivated, discerning individual—isn’t really in vogue right now. But I’ve always been quietly attached to it. I agree with certain criticisms of the canon: that what we consider canonical is usually drawn from an incomplete survey of the cultural landscape (mostly works by white men, mostly chosen by white male critics). And yet the idea that there are certain books, films, albums that are just better than most of what’s out there—and that encountering them can shape your tastes in distinctive and desirable ways—feels so obviously true.

And so the name of this Substack, personal canon, is meant to capture both my antipathy and affection towards the idea. There’s so much out there to read, watch, listen to; how do you decide where to start? Through recommendations, from friends or critics—and in the process, sharpening your own sense of what great work is, and what your personal canon will be.

The Taiwanese filmmaker Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000) is a film that many critics consider canonical—and even before I watched it, I felt like it could be part of my personal canon, too. They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They lists Yi Yi as the 3rd most acclaimed film of the 21st century. Two friends last year (whose taste I trust completely) recommended it to me.

I finally watched it this weekend. It’s my first film of the year and I’m afraid that nothing else in 2024 will measure up to it: it’s visually so beautiful, the characters so tenderly realized, and the nearly three-hour runtime feels perfect for all the joys, struggles, and unexpected tragedies that unfold.

Before I discuss the film, though, let’s talk about Edward Yang a bit.

Edward Yang (1947–2007) was a Taiwanese filmmaker who originally studied electrical engineering before pursuing his cinematic interests in his mid-thirties. After his undergraduate studies in Taiwan, he moved to the US for graduate school—first for master’s in electrical engineering, then for USC’s renowned film school. But he was intimidated and alienated by USC’s commercial approach (“I realized I didn’t have talent at all. I didn’t have what it takes to get into the film business”) and dropped out.

By thirty, he was working in Seattle’s emerging information technology industry, and managing a team that designed microcomputers and microprocessors. A serendipitous encounter with a Werner Herzog film (Aguirre: The Wrath of God) reawakened his interest in filmmaking. The film, Yang said later, “restored my sense of competence that I could be a filmmaker. This is what I thought a film should be.”

Three years later, Yang returned to Taiwan to write the script for a friend’s film. From there, Yang’s cinematic career accelerated: directing an episode of a television series, Taiwanese Women; a short film, Desires/Expectations; then six feature-length films before Yi Yi, the film that cemented his international reputation.

I’m endlessly fascinated by people who did the practical, boring job first before finally recognizing and pursuing their artistic yearnings. In an interview in Cinéaste, shortly after Yi Yi was released, Yang described the parental and cultural pressure that pushed him to become an engineer: “Parents always want you to be in technology, so that when you graduate you can get a good-paying job, and they feel secure. If you're interested in the humanities, they think you're going to starve.”1 It’s a pressure that many can relate to, myself included.

But Yang’s seemingly unrelated studies became a source of strength, when he made the leap from engineering to filmmaking:

I'm fortunate that I started my career not in the tradition of the industry. We had to improvise a lot, to find alternative ways to accomplish something. It makes me feel lucky that I trained as an engineer. Engineering is a practical thing. I call it basically problem-solving, and nothing else. When I started directing, this training gave me psychological readiness. You had to make a thousand decisions a day. Especially in an industry in such poor condition, you had to improvise to make something work. Even to this day, that's part of the process.

And what is a film—or any artistic work—if not the sum of a thousand small decisions?

Yi Yi opens with a wedding: elegantly dressed adults, cherubic and mischievous children posing for wedding portraits as a delicately ceremonial song plays. The Jian family at the center of the film—the father NJ, the mother Min-Min, a teenage girl named Ting-Ting, and the 8 year old boy Yang-Yang—is attending the wedding of Min-Min’s younger brother. Careless and superstitious, he got his girlfriend pregnant and then postponed the wedding so that it could happen on the most auspicious day of the year. The wedding is shown in sweeping, stately shots, with red and green tones pushing against each other in luminous ways:

After the wedding, we move to the intimate domestic and office interiors that dominate the middle of the film. By the end of the film, I felt like I had lived in the Jian family’s apartment with them—the layout felt familiar, the kitchen appliances, the tidily cramped living room.

Yang does long, slow cuts here, so there’s plenty of time to notice all the objects in the rooms: like the hongbao adorning a cork pinboard on the wall, an electric kettle with a red-edged cloth draped over it.

An early crisis—Min-Min’s mother has a stroke on the night of the wedding, leaving her in a coma—affects everyone in the family, but especially the daughter Ting-Ting, who is naïvely and touchingly afraid that it’s her fault. Her guilt, acted out with delicate restraint, was one of the most moving parts of the film for me.

But everyone in the family is quietly struggling with something. The father NJ’s business is failing, and he’s caught up in wistful regret after running into a former lover. The mother Min-Min feels trapped in the empty, repetitive dullness of her life. The young son, Yang-Yang, is bullied by an egocentric schoolteacher.

Their problems are intensified by those outside the nuclear family. The newly married couple show up here and there, with their extravagantly self-destructive financial woes and jealous arguments. And the Jian’s neighbours, a glamorous single mother and her teenage daughter, end up complicating Ting-Ting’s life especially. The film moves with surprising elegance between all these characters and their dramas, individual or interconnected.

In the same Cinéaste interview, Yang noted that his use of actual, contemporary interiors was both a cost-saving exercise and a critical opportunity:

It's cheaper to set a story in the present time, because I don't have to build sets. I can use everything that's right there, and work efficiently with much less cost. If we're sensitive enough, we can put the subject matter into the reality around us and basically tell a story even more effectively. Instead of saying that I have to be a social critic, if you're conscientious enough in that situation, that will be the end result.

Using the family as a frame, Yang can discreetly comment on Taiwanese society at the turn of the millennium—and on human nature in general, really. Through the conscientious father NJ and his reckless brother-in-law the groom, we see how a middle-class hunger for wealth can lead to shortsighted financial decisions. There’s something timelessly, universally relevant about a story where a family member needs to be bailed out after a speculative financial decision gone wrong. It’s very Tolstoyian! And it’s reminiscent of similar situations in my own family—I remember my parents gossiping with great-aunts and grandparents while I, with my uneven understanding of Vietnamese, tried to piece together who had ruined their finances this time.

One of the most interesting aesthetic decisions Yang makes is to show so many moments through some mediating surface. When the Jian family first returns home to their apartment, we see them enter through these Y2K era security displays. They’re very adorably chunky, and in a dated beige that I feel a tremendous amount of affection and nostalgia for—it really feels like all my childhood experiences with technology are contained in this specific color.

More often, however, the mediating surface is a mirror or reflective glass. When the groom’s child is born, the first encounter we see is him peering through the glass with a camcorder in his hand, eagerly waiting to capture the first few moments of his child’s life:

And in two affecting scenes, when the mother Min-Min tries to speak to others (her husband, and her colleagues at work) about her existential loneliness and despair, we see her reflected in other surfaces. In both scenes, it really felt as if the other people there with her couldn’t quite reach her in her suffering. She is as incapable of articulating her distress as her husband and colleagues are to reach her and provide her with any solace and companionship.

It feels as if that psychological unreachability is intensified by depicting her through these reflections. Especially so in the second scene, which is depicted entirely through the reflections in the office windows—Min-Min’s body is physically unreachable as well; we only see her as an indistinct, faraway shadow.

The film has a certain discreet reserve in how the plot advances, but two of the characters end up conveying quite a lot of Yang’s philosophical outlook through their dialogue and actions.

One of those characters is Ota, a Japanese game designer that NJ considers doing business with, is one of the most compelling characters of Yi Yi. In an early scene, we see him idling in a breezeway of NJ’s office building, with a strangely peaceful pigeon perched on his shoulder—very Disney heroine of him!

But it’s an interesting way to show Ota’s instinctual sensitivity towards others, his capacity to understand them and make them feel at peace. In the film, Ota is depicted as an technical and artistic genius—but also someone with a particularly intuitive capacity to understand other people. He recognizes, for example, NJ’s sincerity, as well as the wheeling-and-dealing opportunism of the longtime friends that NJ is in business with.

There’s a scene set in a Tokyo hotel, where NJ has just received a phone call that confirms what Ota has already intimated to him—that NJ’s business partners are unreliable, dishonorable, and incapable of long-term business strategy (the worst capitalist sin of all). For such a pathos-laden scene, it’s very visually cheerful: the bulky beige electronics, the warm light.

The other character that Edward Yang conveys his philosophy through is the 8 year old son, Yang-Yang. There’s a funny and sweet little scene where Yang-Yang interrogates his father about an epistemological anxiety he has:

Yang-Yang

Daddy, I can't see what you see and you can't see what I see

How can I know what you see?NJ

Good question. I never thought of that.

That's why we need a camera.

Do you want to play with one?Yang-Yang

Daddy, can we only know half of the truth?NJ

What? I don't get it.Yang-Yang

I can only see what's in front, not what's behind

So I can only know half of the truth, right?2

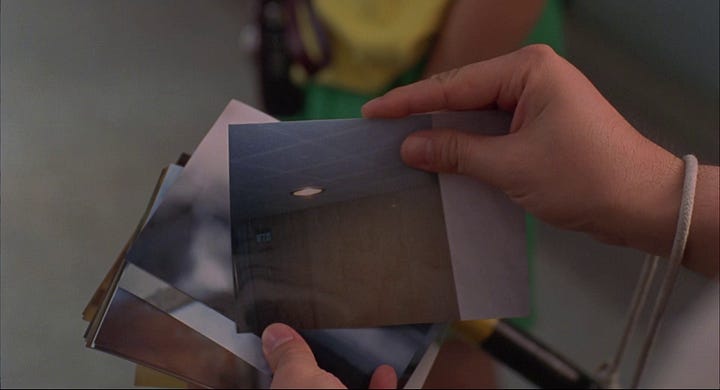

After his father gives him a camera to play with, Yang-Yang fills his first roll of film with stylishly unfocused, avant-garde photographs of—well, nothing in particular.

His second roll is devoted entirely to the backs of people’s heads. Why? Because Yang-Yang is distressed by the idea that we only know half of ourselves, half of what’s going on—and we remain ignorant of the things that could help us through our difficulties.

It’s a charmingly eccentric activity for a child to perform, but with a philosophically intriguing and altruistic belief behind it. Yang-Yang explains his intentions when he gifts one of his photographs to the subject:

The groom [Yang-Yang’s uncle]

What's this?

For me?

This is me!

The back of my head!

What's this for?Yang-Yang

You can't see it yourself, so I help you

Charles Taylor, in a beautiful review of Yi Yi for Salon, notes:

It's one of the odd things that kids do, but it's also a perfect metaphor for what a filmmaker does: He shows us the parts of ourselves that we can't see.

The film is of an ordinary Taiwanese family, with ordinary concerns: a teenage love triangle, an elderly family member’s stroke, a marriage grown distant, a shotgun marriage in the extended family. It’s this ordinariness, depicted through Yang’s careful, quietly tender style, that makes Yi Yi such a moving work.

Numerous critics, in the last twenty-plus years, have written about the cinematic excellence of the film, the cultural impact, its long-term influence and significance. I don’t really know enough about film to speak to those things. I just know that I felt personally attached to all the characters; I was painfully attentive to the disappointments they encountered, the small moments of hard-won peace and serenity they attained.

It’s just a very, very, very good—canonical, even—work.

Three recent favorites

Getting personal in cultural criticism ✦✧ A newly translated novel by Japan’s first Nobel laureate in literature ✦✧ An atmospheric album by Éric La Casa + Seijira Murayama

I’ve been talking to a few friends about how 2024 feels like the anti-algorithm year for cultural consumption. Some of this is a reaction to hitting peak Spotify: it’s no longer interesting to see what Spotify wants me to Discover, Weekly—especially when it’s reflected back to me, in my end-of-year Wrapped, as a supposedly privileged insight into my taste. Jennifer Bin recently described it as “self deception through numbers”—a phrase I keep on coming back to, because it perfectly encapsulates the exhaustion I feel at the relentless quantification of my cultural consumption.

Personalized algorithms can produce an endless regress into what I already know and like—when what I want is novelty, otherness, and intrigue. I’d like 2024 to be a year where I get recommendations from people: friends, critics, publications, all with their idiosyncratic, highly specific investments in a certain kind of music, a certain ideal of how music enters into and shapes a life.

Below: 3 recent favorites I found through people, not an algorithm.

Getting personal in in cultural criticism ✦

This year I’m rerereading Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (a quick, irreverent synopsis: bourgeois gay man gossips about French high society, art, and literature for over 4,000 pages) with a few people on Twitter.3 My Proust reading group is how I met (well, online at least) the writer and scholar Mitch Therieau.

Therieau’s essay “Getting Personal” for the Chicago Review is an excellent investigation of criticism that has “assimilated characteristics of the personal essay.” In this approach:

the critic’s job is to record their responses to works of literature and art; to capture “the way it feels” to be here, now, reading and writing. The critic writes, as Gornick puts it…“to give us back the taste of our own experience.” It is no coincidence that this last formulation comes from her account of memoir.

Here is a new function for criticism: not evaluating the object but reproducing the critic’s experience of the object. Since the turn of the millennium especially, the critic has become chiefly someone who responds, who feels the raw impact of culture on their nerves, and who writes primarily to pass on this unmediated crush of sensation to the reader. They have become a surrogate experiencer.

This form of criticism, Therieau suggests, is less about judging a work than it is about encountering a work. And the formula for this writing is Encounter = object + rhapsodic first-person reaction.

I’ll leave you with one final quote, which I’ve been thinking about a lot in relation to my own writing—where I’m always trying to distill my own experience of a work into something that is interesting, even moving, to a reader:

Much has been made of a recent poptimist or anti-critical turn in the world of criticism, best encapsulated in the webcomic slogan “Shhh…let people enjoy things.” But could it be that criticism now isn’t for letting people enjoy things, but for helping them enjoy things? Or helping them feel anything at all? Personal criticism announces this new vision of the critical essay as a mood-altering technology with special exuberance…despite everything, meaningful aesthetic experiences are still possible.

A new translation of Yasunari Kawabata’s The Rainbow ✦

About once a week I visit Dog Eared Books, the beloved San Francisco bookstore with an unusually good selection of literary fiction (new and used), left-leaning nonfiction, and books on design, music, and photography.

I mostly read library ebooks, which are free and exceptionally space-efficient. But a great independent bookstore is irreplaceable. They often have a well-curated selection of books (sometimes with handwritten staff recommendations on the shelves) that I wouldn’t search for myself. And it’s nice to fall in love, impulsively and instinctually, with a really great cover.

On my last visit to Dog Eared, I was struck by the cover of Yasunari Kawabata’s The Rainbow, newly translated by Haydn Trowell. The cover—beautifully pigmented, indistinct forms, and discreetly elegant typography—is designed by John Gall. You’ve probably come across a Gall cover before: he did the original Haruki Murakami covers, with their distinctive combination of vintage photographs and cutout shapes, as well as covers for books by Michel Houllebecq, Vladimir Nabokov, Ivan Turgenev, and Yukio Mishima.

I like to think I read a lot of Japanese literature, relatively speaking—but I’d never read a novel by Kawabata, who was the first Japanese writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1968.4

The Rainbow is a serenely paced, unsettling novel set shortly after World War II. The novel centers around the three daughters of an architect, Mizuhara, all born from different mothers and, consequently, their own difficulties in feeling included and beloved within the family. It’s quite a heavy novel, touching on suicide, sexual manipulation and violence, fatherly betrayal, and postwar economic struggle. All this is counterbalanced by Kawabata’s delicately symbolic style, which lingers on the beauty of nature and architecture before grazing up against a character’s feelings of passionate despair, violence, and rage.

It’s an interesting novel. I didn’t love it, but I was intrigued by it. And even as I’m writing this, I’m coming to respect how Kawabata handles the tremendous trauma that the eldest daughter has to deal with, and how he ends the novel with a sense of peace, but not total tranquility. Trauma, in Kawabata’s world, isn’t easily erased. It stays with his characters, it continually produces pain. And yet that pain is bearable, livable even—and there is some measure of beauty, some measure of tenderness, to make it all worth it.

My anti-algorithm year of music ✦

One of the special pleasures of January, to me, is going through all those best-of lists and receiving a guided tour of the last 12 months of music.

I’ve been working my way through 2 lists in particular. The first is Resident Advisor’s best albums of 2023 list, which includes some of my favorites—

Caroline Polacheck’s Desire, I Want to Turn Into You, which I obsessively listened to on Valentine’s Day last year, when it was released, before seeing her perform in London the same evening! The perfect date night.

Laurel Halo’s Atlas; I’ve been vaguely following Halo’s work since I saw her at a music festival in 2019, and Atlas is a pristinely beautiful haze of ambient, resonant sound. I especially love the elegiac violin and cello notes, which shift between a grounded, full-bodied depth to something thin, almost scratched away—the barest contours of a stringed instrument.

—and a number of albums I haven’t listened to yet. For the past week, my morning commute has been exclusively devoted to James Holden’s Imagine This Is A High Dimensional Space Of All Possibilities. Many of the tracks have such an expansive, nearly spatial level of complexity, with birdsong coming in from all possible directions, layered above and below. My favorite 5 words from Kitty Empire’s album review in The Guardian: “prelapsarian oscillations, birdsong and bells.”

The other best-of I’ve been working through is the experimental music newsletter Tone Glow ’s recommendations: their favorite albums of 2023, along with the individual recommendations from their 32 writers (part 1, part 2).

I was surprised by how much I liked the strange little album Supersédure 2, recommended by Dominic Coles. It’s a collaboration between Éric La Casa, whose field recordings examine the acoustics of interior spaces, and Seijira Murayama, a percussionist whose practice, across multiple decades, has focused on improvisation and collaboration.

The tracks have quite a bit of negative space, emptiness—interrupted by small, sonic gestures. Field recordings that might be traffic, doors easing open, footsteps. A percussive interruption that departs unexpectedly, leaving you with a void for contemplation. More field recordings: you’re indoors, you’re listening to objects reverberate against each other. Then you’re outdoors: an engine starts.

Because I love intimate encounters with architecture—humans entering buildings, living in them, furnishing them, experiencing them—I am of course obsessed with this note, from Éric La Casa, on his fascination with interior spaces:

I spend more time inside than outside. In Paris, my existence is organised in the interior volumes of anthropocentric architecture: the apartment, the shop, the Métro, the café, the library, the cinema, etc…

I examine this interior world, its materiality, its acoustics, its furniture, its inhabitants, and so forth. Over the years, my exploration of the fullness and emptiness of these spaces has led me ever further into the liminal sonic dimension of everyday life. From the overt to the inaudible, I experiment with its dimensions, repel its indeterminacy.

As I write this, I’m listening to Supersédure 2 in my room, and in the negative space of each track I’m noticing the soft slashes of sound from outside my window: cars passing by on the wet streets, the wind audibly pressing against the Victorian houses lining my street, a delicate sonic layer of rain.

If you’ve read all the way to the end: thank you. I’m genuinely very, very touched and it feels really special to share these reflections on film, literature, and music with you. Wishing you a beautiful week ahead and an auspicious start to 2024.

Edward Yang’s Cinéaste interview from 2000 is available on JSTOR. I recently discovered that a San Francisco public library card gives me access to a lot of JSTOR, but also—a kind stranger on Douban has transcribed the entire interview as well!

Once again I am relying on the kind strangers of the internet—specifically, whoever added the complete English subtitles of the film to this website I’d never heard of before.

I know I should be writing “X, formerly known as Twitter” but calling it X is just so inelegant, I can’t stand it!

Yasunari Kawabata’s biography is actually quite tragic—maybe that’s why The Rainbow deals with such difficult family dynamics! Kawabata was born in 1899 in Osaka, and his childhood years were marked by death after death. By the age of 4, his parents had died. He and his sister were separated (she died by the time he was 11) and Kawabata went to live with his grandparents. Then they both passed away by the time he was 15.

Just watched Yi Yi on your recommendation and have to say it’s an instant favorite!! Thank you much.

Great piece! Enjoyed all the photos that complemented it as well.