best books of 2024

including novels, nonfiction, short stories and essays ✦✧

Too much to read, too little time. It’s easy to think that this conflict is a distinctive feature of contemporary life, caused by mass literacy, the printing press and the internet. But as the historian Ann Blair has observed, the feeling of information overload has surprisingly ancient origins. According to the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who lived from 4 BCE to 65 CE, ancient Rome was inundated with books—most of them bad. In Too Much to Know, Blair writes:

Seneca complained…that his well-to-do contemporaries wasted time and money accumulating too many books. He coined a tag of his own to decry their indiscriminate and superficial way of reading: “the abundance of books is distraction” (distringit librorum multitudo). Instead Seneca recommended focusing on a limited number of good books to read thoroughly and repeatedly: “You should always read the standard authors; and when you crave change, fall back upon those whom you read before.”

But I can’t quite agree with Seneca. I value novelty and contemporaneity—as did the 14th-century bishop and bibliophile Richard de Bury. In The Philobiblion, a collection of 20 essays on acquiring, organizing and lending out one’s books, de Bury wrote: “It is meritorious to write new books and to renew the old.”

It’s also a virtue, as I’ve suggested before, to read new and old books. In 2024, I read 110 books, mostly from the 20th and 21st century, although some older works made their way in. Reading across centuries, genres and topics has convinced me that there’s always a great new book out there, and that contemporary literature can hold its own—in artistic ambition and execution—against many of the “standard authors” of the past.

Below, a somewhat idiosyncratic list of the best books I read in 2024, in the following categories:

Fiction: 6 novels, 1 short story collection (and 3 standalone short stories)

Nonfiction: 3 books on cybernetics, clubbing and cultural capital; 4 memoirs/diaries; 3 academic works; 6 essay collections

Experimental: 3 books that defy description and categorization

I’ve also (meticulously and somewhat pointlessly) noted the year each book was published. For works in translation, I also include the year it was translated and the name of the translator.1

Fiction

Novels

I read a lot of very good fiction this year, but my favorite novels tended to focus on:

What to do with the restless intellectual energies within you

How to move through time with dignity and curiosity

How to commit to love but not self-flattering delusions

They include one novel from the 19th century, and five from the 21st century:

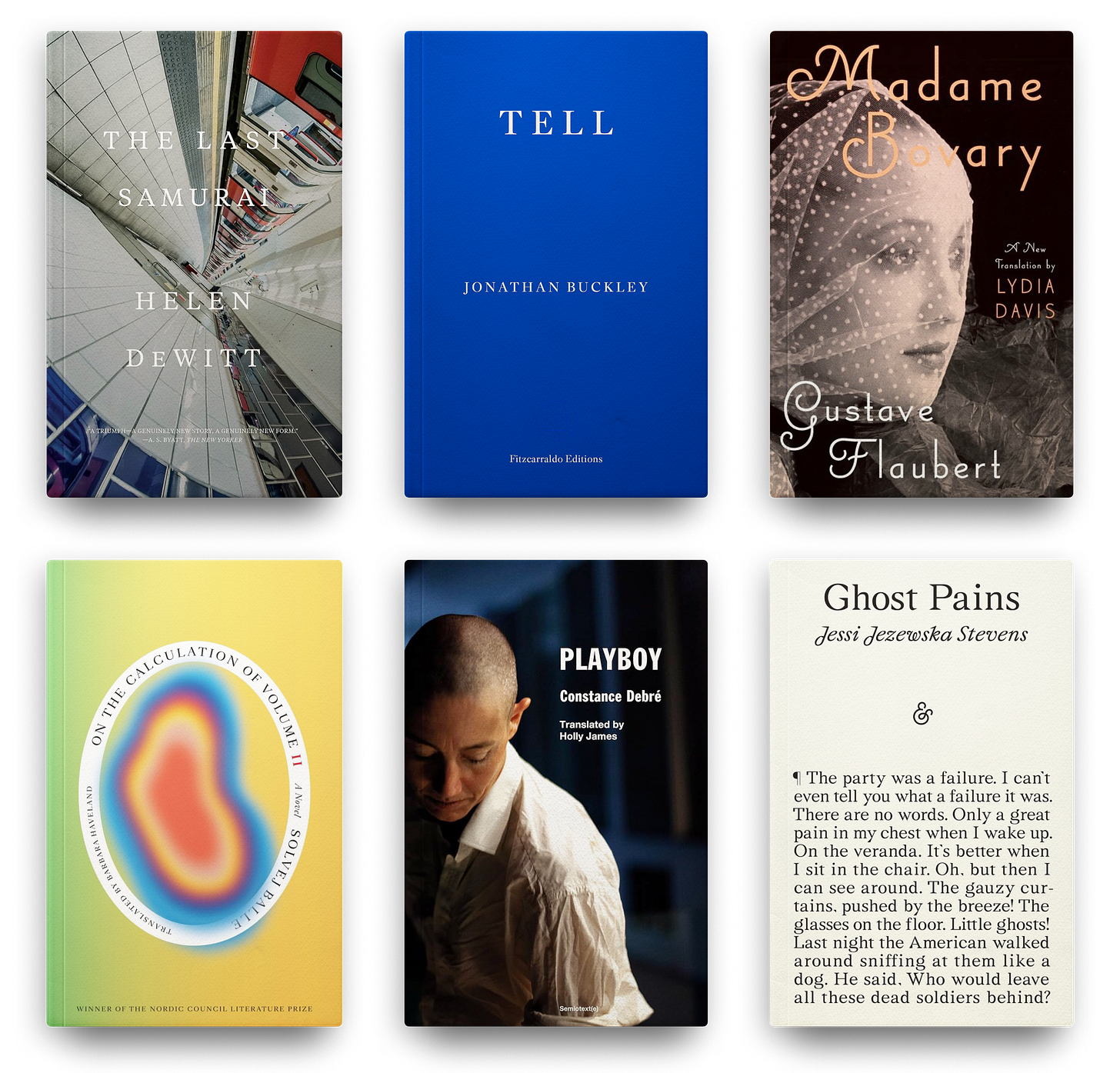

Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai (2000) is one of the greatest English-language novels of the 21st century. It’s about a brilliant and strange woman raising her unusually gifted son alone, and the story—inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s film Seven Samurai—reflects on the influence of our parents, how geniuses are raised, and becoming a polyglot.2 I wrote about it in October; it is one of the most life-affirming novels I’ve ever read.

Jonathan Buckley’s Tell (2024) is one of those formally innovative novels that draws you in on a deep, visceral, emotional level—not just an intellectual level. In Tell, a gardener for a wealthy British billionaire is interviewed about the billionaire’s working-class beginnings, the glamorous and powerful women in his life, and his art collection. It’s a very gossipy, voyeuristic novel about how wealth and greatness distorts our perception of men; it’s also a really moving look at childhood abandonment and the lasting rewards of love and marriage. It’s the kind of great work that makes you want to write in new, bold ways—which I tried to do in my review for atmospheric quarterly.

Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856 in French/translated in 2010 by Lydia Davis) is obviously a great, revered work—but when I read it in October, I was surprised by how incredibly well-paced it is, and how much it resonates with very contemporary, familiar concerns: marrying someone and then despising them; wanting luxury and romance and losing yourself in the pursuit of both; letting your understanding of reality be entirely destroyed by the romances available in novels.

Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume (2020 in Danish/trans. in 2024 by Barbara J. Haveland) is a Scandinavian septology—they love their seven-volume books over there!—about a rare-book seller, Tara Salter who wakes up one morning to discover that she’s living the same November 18, over and over, and she is entirely alone in this experience. 2 volumes have been translated into Englihs so far. In volume 1, Tara Salter tries to discover the rules of this new temporal regime (this is fascinating to read, like watching a scientist at work) while feeling increasingly lonely and isolated from her loved ones. I shared a quote from vol. 1 here. In volume 2, she finds a way to celebrate Christmas and live according to the seasons—as best as possible, because she’s still trapped in November 18!—and becomes obsessed with researching the roman empire (a literary example of why research is the ultimate leisure activity!). It’s so good; and I loved what Catherine Lacey had to say about the novel:

As I read, I slowly had the feeling I was being allowed to see under the hood of life, that I was somehow looking at the mechanics of the experience of successive moments, of memories, of loneliness, of the texture of living. The cycles of a love, the cycles of childhood and adulthood, the interconnecting loops between different eras in your life— I was dizzy with it all.

Constance Debré’s Love Me Tender (2017 in French/trans. 2022 by Holly James) and Playboy (2018/2024 by Holly James) are the first 2 books in Debré’s autofictional trilogy about abandoning a bourgeois, respectable, heterosexual life and coming out as a lesbian. In Love Me Tender, Debré uses a remarkably unsparing, coolly unsentimental voice to describe her struggles with her ex-husband, who tried to use Debré’s queerness to prevent her from seeing their son. Playboy is a frank depiction of Debré’s pursuit of women. No one writes like Debré. And the lack of sentimentality feels very fresh and unexpected.

Honorable mentions (great novels that I would recommend unreservedly, but of less personal significance):

Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood (2023, a masterful literary thriller with extremely psychologically insightful character portraits, some of which I shared here; highly recommend BDM’s review of it for the New Yorker as well)

Honoré de Balzac’s The Lily of the Valley (1835 in French/trans. 2024 by Peter Bush; here is my irreverent summary of the novel’s love triangle)

Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021; I have a deep affection for epistolary novels and uncomplicatedly happy endings) and Intermezzo (2024; compulsively readable, as all of Rooney’s novels are, and a lovely exploration of the arbitrary barriers we create to block us from finding love; I listed my favorite reviews of the novel here)

Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s The Revolutionaries Try Again (2016; an artistically ambitious novel about an idealistic man growing up and figuring out how he can actualize his youthful political ambitions—and if he even should)

Short stories

While the length of a novel offers the opportunity for a sweeping, expansive narrative—and ideally a satisfying, cathartic conclusion—a short story offers something different. My favorite short stories have:

A memorable and original concept

Italo Calvino and César Aira are exceptionally good at this, and both are exceptionally skilled at taking a mathematics or physics concept and turning it into a storyA lingering emotional resonance

Typically melancholic, wistful, tragic; as Joy Williams noted, the short story “is not a form that gives itself to consolation”A large quantity of highly expressive, remarkable sentences

Williams, again, suggests that an “essential attribute” of the short story is “Sentences that can stand strikingly alone”

This year, my favorite short stories were:

Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s Ghost Pains (2024) is such a good short story collection—I remember reading it and thinking, This is going to be one of the best reading experiences I have in 2024—because it has all the qualities above. Stories like “Weimar Whore”—about a woman who becomes convinced she is living in Germany’s interwar period and conducts her financial and romantic affairs accordingly—satisfy the memorable and original requirement. Many stories, including 2 about couples traveling together, have such intensely insightful and painful depictions of what it’s like to be in love and still feel lonely (the lingering emotional resonance requirement). And Stevens is such an obviously good writer; her sentences are beautiful and precise.3 I wrote about Ghost Pains back in July and included some quotes as well.

Sterling HolyWhiteMountain’s “False Star” (published in the New Yorker in March 2023, but I only read it this year!) is about a young man from the Blackfeet Reservation turning eighteen and figuring out his approach to his mentors, the great love of his life (so far), and what it means to grow up. The story moves beautifully between a great deal of activity and urgency—dialogue, confrontations, drunken nights, flirtations!—and a deep, steady interiority as the young man observes the people around him:

There had been something about her even when she was young, not a woman or a young woman but still mostly a girl, something that made men, older men, pay attention. She changed when they looked at her and the more they looked at her the more she changed and I had been around and borne witness to this and had myself in the process been altered..

With the best short stories, I feel a strange sense of loss when they end; it’s as if someone tremendously vivid—almost more real to me than the people from “real life,” the life lived outside literature—has passed through my life and is now lost to me. Maybe you know what I mean, and you know how precious it feels to find a story that creates that feeling.

Angelo Hernandez Sias’s “Customs/Psychological” (2023; I wrote about it back in June) and “Trying to Establish Myself as a Young Man” (2024) both capture the bravado, anxiety, egocentrism, humility, banality and beauty of being young in a way few other short stories do. Hernandez-Sias has a real gift for dialogue and for the little colloquialisms and strange turns of phrase that informal speech can take; I love how he draws in actual speech, text messages and emails into both stories. “Customs/Psychological” is my favorite—more chaotic to read, more satisfying—partly because the ending has a particularly intense quality to it—a kind of crashing, instantaneous awareness where the protagonist becomes aware of his own failures of integrity, his own inability to decide what he wants (which is, I think, the great dilemma of being young!) in small failures of integrity. But “Trying to Establish Myself as a Young Man” has a kind of smooth, restlessly observant everydayness that makes it easy and entertaining to read. I loved this part:

I stood organically by Yadi, sipping and saying I would like to delete my “discography” and renounce music. Angst o’clock, she said removing the drink from my hand and taking my hand in hers and pulling. Do not delete your music OK it is an inspiration to some of us you have no right. And it’s just a dance chamaco but suit yourself. Oh all right, I said. It felt good to touch her waist again, warm and swaying under my palm. Not so stiff, she said squeezing the back of my neck. I’ve been taking lessons in Dominican masculinity from Francisco but I’m a slow learner, I said, forgive me. Dominican men don’t ask forgiveness, she said. We must be reading different Junots, I said. You’re still reading Junot, she said. She pinched my nose and set her head on my shoulder for a slow song, like she did for the long train to Kenneth’s show. When we got off the lower sky was visible in the absence of high rise.

Nonfiction

I’ve split this up into 4 categories: general, memoirs and diaries, academic monographs and essay collections.

On cybernetics, clubbing, and cultural capital ✦

Dan Davies’s The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions – And How The World Lost its Mind (2024), which seems like a book about the sometimes-catastrophic consequences that technological and economic systems have had on society. And it is! But it’s also: a very accessible and engaging history of cybernetics; an insightful analysis on why research into AI explainability might not fix anything (here’s a quote); and an extremely useful explanation of what value (or perceived value) consultants bring to an organization. It’s very possibly the most intellectually original (nonfiction) book I’ve read this year, and the conclusion includes an unexpected and delightful story about Brian Eno’s interest in cybernetics.4

Emily Witt’s Health and Safety: A Breakdown (2024) uses Witt’s own experiences—as a lonely New Yorker who finds community in techno clubs; as a woman caught up in a tumultuous romantic relationship with another techno head; as a journalist writing about the Parkland high school shootings and Black Lives Matter protests—to write about much broader themes. It helps if you’re a little bit into techno (and therefore find the references to specific DJs, clubs and parties exciting instead of aggravating); it also helps if you believe that writing about the dissolution of a romantic relationship is not inherently unethical, even if the result is unflattering for Witt’s ex and herself. I found this exceptionally moving and beautifully written.

W. David Marx’s Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change (2022) is a sweeping, sociologically comprehensive book about how our tastes—in everything from haircuts, handbags and hobbies—are influenced by a conscious or subconscious pursuit of status. Marx isn’t being cynical, just descriptive, and the book offers very accessible introductions to key sociologists and their theories to describe how subcultures and fashion trends are powered by these status dynamics. If you’re are someone who takes your taste seriously—and especially if you have self-consciously cultivated a particular look through fashion and style decisions—Marx’s book is a must-read.5 (For a shorter read, and more narrowly focused on Japanese/American fashion history, I also recommend Marx’s first book Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style.)

Memoirs and diaries ✦

Marion Milner’s A Life of One’s Own (1934), originally published under the pseudonym Joanna Field, is is about the British psychoanalyst’s “seven years’ study of living,” where she sought to record her actions and emotions, and see if she could “discover any rules about the conditions in which happiness occurred.” The result is a candid, introspective and deeply insightful analysis on how consciousness works, where despair and suffering emerge in ordinary life, and how to combat these feelings and attain a sense of agency and courage.

Brian Eno’s A Year with Swollen Appendices (1996) chronicles a year in the ambient musician and producer’s life. The book is an engrossing, charming look at Eno’s wide-ranging interests, and the “swollen appendices” include essays on interdisciplinary thinking, generative art, how celebrities can contribute to charitable projects…and there are some really fun little sci-fi short stories included! It was so exciting to see the breadth and depth of Eno’s concerns—which you can also see in the latest issue of the Boston Review, where Eno has written a brief and characteristically insightful response to how AI should (and shouldn’t) be used by artists.

Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman and the City (2015), which I wrote about back in March, amazed me with the sheer quantity of extraordinary writing. There are memorable, precise, vivid character portraits; the way Gornick inspects her own mind (and her own strengths and flaws) is full of rigor and honesty; and it’s also a lovely depiction of Gornick’s life in NYC, her career as a writer, and how decades-old friendships have shaped her.

Sigrid Nunez’s Sempre Susan (2011) is about Nunez’s relationship with Susan Sontag. It began in a funny way: In 1976, Nunez assisted Sontag with some clerical work and had a brief encounter with Sontag’s son, David Rieff. After Rieff expressed some interest in Nunez, Sontag engineered a subsequent meeting between the two—and, when Rieff and Nunez began dating, Sontag suggested that Nunez move in with the mother and son. Sempre Susan is about the years that Nunez lived with them both; it’s also about the enormous influence Susan Sontag had on American literature, and on Nunez’s aspirations as a writer. It’s funny, tremendously insightful, and generous to Sontag’s legacy—but Nunez doesn’t flinch away from describing the strange, frustrating traits that Sontag had.

Academic monographs ✦

I have a special affection for scholarly books. The best ones are not difficult to read—they’re very structured and therefore easy to scan—and the deliberate, deep focus on one topic can be immensely rewarding. A really good monograph uses its constrained focus to draw more principled, substantiated conclusions on topics of broader concern.

My favorites this year:

Chaim Gingold’s Building SimCity (2024) is a history of the iconic videogame SimCity and a depiction of broader trends in 20th and 21st century computing, city planning and children’s education. I’ve praised Gingold’s book extensively in my LA Review of Books essay, “Seeing Like a Simulation,” so what I’ll say here is: if you are interested in software (as a practitioner, historian or critic) this is one of the best books you can read about how software development works—and how a single software product can be influenced by broader intellectual fields.

C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art (2020) is a philosophical argument for treating games as an art form, but it ended up sharpening my understanding of how humans interact with art more generally—and what is distinctive about different mediums. I read this as research for my review of Building SimCity, but it’s really shaped how I think about novels and paintings and architecture as well.

David L. McMahan’s The Making of Buddhist Modernism (2008) is a religious studies monograph that discusses how and why Buddhism became so influential in the west, and how certain practices—like meditation and mindfulness—have become “desacralized,” and understood as scientifically-backed behaviours instead of religious rituals. I read this back in April and summarized some of the key ideas in my Goodreads review. McMahan’s book also includes a very useful summary of the key ideas of the Enlightenment and European Romanticism, and how those ideas were synthesized into our contemporary understanding of Buddhism.

Honorable mentions (books that felt revelatory and intellectually exciting, but where I only read a few chapters):

Achen and Bartels’s Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government (2016; discusses how we think democracy works and the empirical evidence that contradicts that)

Émile Durkheim’s Suicide: A Study in Sociology (1897 in French/trans. in 2002 by George Simpson for Routledge; an iconic work whose methods shaped sociology and the social sciences more broadly)

Fred Turner’s The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (2013; includes a fascinating discussion on the influence of Bauhaus artists/designers on American media culture and propaganda)

Jacob Gabourey’s Image Objects: An Archaeology of Computer Graphics (2021; an excellent history of computer graphics research and reveals how many advances came from French researchers and those at the University of Utah).

Essay collections ✦

Six essay collections that gave me revelatory and exciting ways to think about technology, philosophy, romance, art, history…

Meghan O’Gieblyn’s God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning (2021) is a philosophically rich and deeply insightful book. O’Gieblyn suggests that the spiritual and eschatological questions (the nature of humanity, consciousness, death, life) previously previously explored through religion are now being explored through our encounters with technology and artificial intelligence. It’s fascinating to see the unexpected connections O’Gieblyn draws between AI theorists and Christian theologians.

Sally Olds’s People Who Lunch: On Work, Leisure, and Loose Living (2022) feels like such a genuinely fresh and exciting approach to cultural criticism. Olds has a remarkable talent for taking on tired topics (polyamory, personal essays, cryptocurrency) and writing about them in unexpected, charming, deeply entertaining ways. Reading this was so invigorating! I especially recommend the final essay, which—improbably and brilliantly—is about Lana Del Rey fans and crypto believers.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light: 100 Art Writings, 1988–2018 (2019) is a collection of the late New Yorker art critic’s writings on artists like Velázquez, Willem de Kooning, Jenny Holzer, Peter Hujar and Florine Stettheimer. Schjeldahl’s long career meant that he wrote about most of the modern greats, and he could put them in context with their peers and predecessors. The book is also so fun to read—Schjeldahl has a peerless style that invites you into a painting and captures the vivid, visual immediacy of art in equally vivid, compelling prose. I reread passages from Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light often—there’s so much to learn from how Schjeldahl handles language.

becca rothfeld’s All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess (2024) ended up being the essay collection I discussed the most with friends! Rothfeld’s writing feels so rich in ideas—ideas that I can’t help but bring to understanding my own life or the lives of others. A lovely example is her essay on the director David Cronenberg (also in the New Yorker as “All Good Sex is Body Horror”), which expands beyond the usual remit of film criticism and addresses consent, love and desire in exciting and novel ways.

Lucy Ives’s An Image of My Name Enters America (2024) is another essay collection full of vivid, compelling writing. Ives, a poet and novelist and critic and (if that’s not enough already!) comparative literature scholar, shifts so easily between a “disarmingly irreverent” style (as I wrote in my review for The Believer’s fall issue) and scholarly seriousness. I loved reading Ives’s analysis of everything from Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem trilogy to French post-structuralist theory.

Phil Christman’s How to Be Normal (2022) takes on familiar topics like masculinity, middlebrow culture, the Midwest, marriage and more. But Christman is such a careful, conscientious writer of deep integrity and humor—and each essay renews these topics in a fascinating way. I wrote about Christman’s book back in September, and here’s a quote I loved from the essay “How to be Midwestern.”

Alongside these collections, here are 9 standalone essays that I found myself rereading this year:

On literary translation: Anton Hur on the difficulty and rewards of translating Korean literature. “I would joke that my mission was to change the face of Korean literature in translation…[which] I would say just to sell a few more books, but frighteningly enough, people started taking the joke seriously.” (June 2023)

On the intersection of literature and physics: Joshua Roebke’s Aeon essay on Spanish-language novelists who trained as physicists, and how their stories became “laboratories of the impossible.” (December 2024)

On thwarted love stories: Tony Tulathimutte on “flat desolation” of the rejection plot. “Rejection isn’t the same as heartbreak, which entails a past acceptance. A rejection implies that you don’t even warrant a try.” (April 2024)

On losing love and searching for it: jamie hood’s diary of the week before surgery, a deeply intimate look at love, sex and desire. (December 2024)

I want to tell myself it’s wondrous I had eight hours of joy with someone, that I felt so astonishing and so wanted, that I was still able—as I have not lately been able—to imagine myself in love again. I try to believe my hope is a glimmering, irreducible thing, especially after the life I have lived…Today, though, my hope mostly feels like an unmissable target I’ve drawn on my own back.

On self-sabotage and agency: R Meager on finishing your projects and how terribly, tragically common it is to ruin your life by not even trying to do what matters most. When it comes to self-sabotage, Meager writes, “It’s not about how smart someone is…[and] also not about moral courage or discernment.” Academics don’t submit their papers; people looking for love don’t go on dates. “All of this is sabotage. It’s everywhere. We like to hear stories where this is the middle. In real life, there are stories where this is the end.” (September 2023)

On living: Michael Rance on living the wrong life (August 2024)

It's alluring to think of the ‘wrong life’ as something that is comically worse than the good things we love…But the wrong life strikes me as a thing of degrees, where you can be living some form of the wrong life while also doing things that are clearly part of the good life. That’s what I’ve begun to see in myself; a prevailing funny feeling that I’m not living in the right way, even though I am doing many of the things that ought to bring me joy.

On therapy and how it can (and can’t) help: Lily Scherlis on the history of dialectical behavioral therapy, and the difficulty of balancing individualized self-improvement with an awareness of the “harshness of reality” and “the world’s irrational injustice.” (July 2024)

Most people I spend time with — leftists prone to anxiety and depression — are skeptical of “self-improvement.” Many of us, following the critic Mark Fisher, think that depression reflects an encounter with the harshness of reality, rather than a merely pathological distortion. We definitely want to feel better, but we don’t want to be hijacked by acronyms or worksheets or positive thinking in the process.

On day jobs and artistic practice: Megan Marz on day jobs and where they help—or hurt—an artist’s career. It’s a review of an art exhibition first shown at the Blanton Museum in Texas last year, and then at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford this summer. Marz’s reflections, which touch on the central conflict between making art and making money—because how many people are able to do both simultaneously?—are fascinating and thought-provoking. (May 2023)

In the end, the art in Day Jobs is not demystified by its source material as much as the day jobs are remystified by artistic success. The only way for this effect not to have occurred might have been to show unfinished, unrealized, or nonexistent art: what artists couldn’t quite bring to completion, or couldn’t even start, because they were too busy with, or tired from, their jobs. But no one wants to see that, no matter how much more representative it might be.

On consumerism stifling creativity: Sheila Heti on whether artists should stop shopping in order to focus on their work. (May 2018)

Shopping is a form of creativity. When I am writing well, I feel no need for shopping. The times in my life I have shopped a lot, it is because I have not been writing…When I have written on my computer, I have my riches there in front of me. When I have shopped online, the riches take days or weeks to come, and when they arrive, they no longer feel like riches. They are never all I hoped they would be. They are objects.

Experimental

Although these books could be categorized on other ways—as memoir (Heti) or fiction (Chevillard, Castaldi)—I wanted to carve out a special category for works that felt memorable because of their sheer inventiveness:

Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (2024) is a fascinating work. Heti took over ten years’ worth of diary entries, entered each sentence into a spreadsheet, and then sorted them alphabetically. The book—a carefully edited selection of the results—is one of the most exciting books I read this year. Although Heti is well-known and highly regarded, I still think she’s tremendously underrated as a literary innovator. As I wrote in ArtReview, Heti is often described as a writer of “autofiction,” but to understand works like Alphabetical Diaries, we should be placing her in “a different lineage of artists and writers…less Knausgaard, more Oulipo and Brian Eno.”

Éric Chevillard’s Museum Visits (trans. in 2024 by Daniel Levin Becker), is so purely fun and eccentric. It’s a collection of 34 micro-essays, loosely about art and cultural institutions. But the writing usually isn’t about anything; it feels more like Chevillard playing with language and letting his irrepressible, irreverent voice charge forward. Some quotes and online excerpts here, from when I wrote about it in January. If you’re an Italo Calvino or César Aira fan, there’s a very similar kind of inventiveness in Chevillard’s writing!

Marosia Castaldi’s The Hunger of Women (2012 in Italian/trans. 2023 by Jamie Richards) is a novel about an older Italian widow who opens a restaurant in a small Italian town, and ends up in (several!) scandalous lesbian romances. Stylistically, the distinctive thing about Castaldi’s writing is the lack of periods—it’s very exciting to see how this changes the experience of reading, and how surprisingly normal it feels to have sentences surge forwards, one after another, uninterrupted by any typographic breaks. It’s also a great read if you’re interested in descriptions of food—Castaldi writes about cooking in a very direct way, with precise and specific detail instead of overly metaphorical language.

Best disappointments

In my best books of 2023, I included a section for best disappointments—books that were worth reading (I’m not going to spend my finite time alive reading books that are genuinely horrible!) but still lacked something.

I wanted to do that again this year, because slightly-disappointing books—even more so than my favorite books—help me understand what I value and look for in writing.

Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (2024) is a nonfiction book about women artists and intellectuals that could be loosely described as unruly, monstrous, unfeminine and transgressive. The women and artworks included are all incredibly fascinating! But the structure of Art Monsters felt slightly dissatisfying and disorganized. Dalya Benor’s review—which I found incredibly insightful and precisely argued—explains some of the problems with this style of hybrid writing (combining art history/cultural criticism/personal narrative) and why it’s frustrating to read fragmentary nonfiction. (Out for 2024: hybrid writing?)

Rachel Kushner’s novel Creation Lake (2024), which has such compelling setup (a competent, morally vacant spy infiltrates a French eco-activist) but doesn’t quite deliver on the promise. I wrote about my disappointment back in November, but essentially: It is frustrating to read a novel about a protagonist with no morals and basically no goals—I don’t actually believe that real people are like that!—and frustrating to read a novel that seems like a spy thriller but is actually very, very slow-moving. I found myself constantly highlighting passages that were interesting and sharp and funny, but the novel as a whole was unsatisfying.

Rosalind Brown’s novel Practice (2024). In theory I have a great affinity for life-of-the-mind novels that are concerned with the restless, interior machinations of the soul and how it stretches towards ideas and intellectual stimulation. (Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19 is essentially this novel, and it’s extraordinary.) But Brown’s Practice, about a day in the life of an Oxbridge undergraduate procrastinating on her Shakespeare essay, is just so still—so drawn-out and devoid of forward momentum; and what began as introspection ends as the protagonist’s excessive self-absorption, I feel. There’s some beautiful and surprising and funny writing in here, but I would have liked more…eventfulness?

Adam Phillips’s On Giving Up (2024) and On Wanting to Change (2021). Phillips is a psychoanalyst and literary critic, and whenever I read his work, my emotions shift from sentence to sentence—from This is so singular and brilliant and explains everything about human nature to I have never seen a more overburdened, comma-heavy sentence in my life, and I’ve learned nothing from it. This effect is heightened in his essay collections, which usually have 1 or 2 sublime essays and then a few mediocre ones for padding. But the sublime essays really are sublimes. Two of my favorites, published in the London Review of Books: “On Giving Up” (on Kafka/Hamlet/suicide/tragic heroes, which led to the collection of the same name) and “On Getting the Life You Want” (on Richard Rorty/pragmatism/Freud/psychoanalysis, which presumably will be the sublime essay at the center of a future book).

December is, of course, when every newspaper and magazine comes out with their “best books of 2024” list (or, in Lithub’s case, the list of lists that shows which books were most frequently recommended). But I find myself most interested in the individual and idiosyncratic lists—like Patrick Nathan’s year in reading, Michelle Santiago Cortés’s books read and films watched, and Helena Aeberli’s reading notes, and Michael Rance’s favorite newsletters of 2024.

(And if you’ve written an end-of-year roundup, feel free to link it in the comments!)

I like these personal lists because they feel closer to the true experience of reading. We read based on our own interests (and not arbitrary rules, like “books published this calendar year”); and what qualifies as best is some function of objective quality and subjective preference.

And it’s been surprisingly fun—and intellectually very rewarding—to take the time to write my own best of 2024, and think about the books that shaped me this year.

Thanks for reading this, and wishing you a satisfying conclusion to 2024!

One thing I’d like to do more in this newsletter is honor the work that translators do. As a reader, I’m indebted to the careful, patient attention of translators like

Sophie Hughes, who translated the Mexican writer Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season, and shared her process in a fascinating New York Times article—it really shows how much labor goes into each sentence!

Jennifer Croft, who translated the Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk’s books into English, and insists that translators deserve to appear on book covers alongside the original author’s name. As Tokarczuk has said,

[Croft] is incredibly linguistically gifted…[she] does not focus on language at all, but on what is underneath the language and what the language is trying to express. So she explains the author’s intention, not just the words standing in a row one by one. There is also a lot of empathy here, the ability to enter the whole idiolect of the writer.

Anton Hur, who translated the Korean writer I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki and has written about how translators can challenge cultural stereotypes and bring more attention to writers in other languages—especially non–FIGS (French, Italian, German, Spanish)

On the topic of “how to raise a genius”—the nonfiction newsletter complement to DeWitt’s book is Erik Hoel’s 3-part series on aristocratic tutoring and how geniuses were raised in the past.

I love Stevens’s nonfiction writing as well. While drafting this post, I read the German writer Ernst Jünger’s novella On the Marble Cliffs (translated by Tess Lewis) which includes an excellent introduction from Stevens.

Jünger’s legacy is complicated. He was militaristic, anti-democratic and deeply conservative, and much admired by Hitler. But he also rejected multiple overtures from the Nazis—he declined a seat in the Reichstag, and an invitation to appear on a radio show hosted by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda. Stevens’s introduction conveys the subtlety of Jünger’s stances, while also cautioning against the desire to sanitize Jünger’s image:

To my reading, On the Marble Cliffs is a daring but ultimately inward-looking achievement. It is as if Jünger built himself an ivory tower in which to wait out Germany’s darkest decades. He never left. Nor did he repent. Until his death, Jünger dismissed criticisms of his wartime behavior. As he aged, he appealed to the growing asymmetry between himself and his younger critics: You weren’t there.

Here is my very irreverent summary (which may also contain some inaccuracies; to get the actual story, you should really just read Davies’s book!)…Brian Eno meets with Stafford Beer, the British cybernetics enthusiast, and Beer says: I’m looking for someone to continue my legacy and advance all this important work on cybernetics that I’ve devoted my life to, and you seem like the perfect person for this.

But Eno demurs and says that he’s so sorry; among his many interests is this new thing called ambient, and he has to work on that instead…

Regarding taste: I keep on thinking of becca rothfeld’s interview with Defector this spring, where she said:

Part of taking aesthetic judgment seriously…is you think it really matters if somebody has bad taste. You might even think that it's a moral failing if somebody has sufficiently bad taste of a sufficiently bad kind.

To draw a direct connection between someone’s taste and their moral capacities is, of course, not always appropriate! But I think Marx’s Status and Culture beautifully describes why we might do so, and why someone’s taste has such immense signaling power—we do, in fact, expect people’s musical and sartorial and literary preferences to express something significant about them.

I always appreciate lists like this that don't *just* focus on books that came out *in* 2024, partially because newer books are not necessarily better than older ones, but more because there tends to be a sameyness to year-end lists when you limit the contents to 2024 releases. I think this is going to be the list that convinces me to read "The Last Samurai," which a lot of people in my orbit have been reading as of late, but "Agency as Art" also strikes me as really interesting.

My personal list of "books I read this year" only has between a dozen and twenty titles on it - which puts me well above the median American but still feels like too few, especially when I consider how many of those books I picked up almost entirely because I've had coffee with the author. Not that those books were bad, mind you. (I think most people on this corner on Substack are wise to the brilliance of Naomi Kanakia, but I'll stump for Anna Shechtman's "Riddles of the Sphinx" - a compelling memoir, but also probably the best book ever written about puzzlemaking, and I've read a lot of 'em.) On the other hand I really liked all the late 20th century lit-fic-adjacent titles I read and am now actively seeking out more books by their authors.

Perhaps my list is thin enough that I can and should do write-ups on all of those books. (It'll be a nice break from writing about all the films I saw this year... which I am going to have to limit to 2024 releases I saw at the multiplex, to keep the number down to just double digits... gurkk...)

Debré is my favorite new to me author of 2024. I just love a fuck-you attitude and a relentless pursuit of authentic selfdom but what I think she does so differently is that she shows that ALL THAT comes at a cost. Lauren Elkin is translating the third book in the trilogie and I just can't wait for it.