and since i have never said ‘youth must end,’ youth will not end

Flaubert on turning 31 ✦ and mathematical models for when to commit

This is a short newsletter, I promise. It’s just that today—my 31st birthday, also known as new year’s eve—is the perfect occasion for a Flaubert quote that I’ve been carefully hoarding all year.

On December 11, 1821, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert sat down to write a letter to his lover, the poet Louise Colet:

Tomorrow I shall be 31. I shall have passed that fatal age of thirty, which ranks a man. That is the age at which you assume your future shape, take your place in society, embrace a profession.

He had already begun working on Madame Bovary at that point, and despite all the difficulties he encountered in writing the novel, it seems to have contributed to a feeling of purpose and self-possession. “Today,” he wrote in the letter,

I am overflowing with serenity. I feel calm and radiant…And since I have sacrificed nothing to the passions, have never said “Youth must end,” youth will not end. I am still full of freshness; I am like a springtime. I have a great, flowing river in me, something that keeps churning and never ceases.

I love this idea—that one’s thirties can be full of vitality, youth and momentum. And I love how Flaubert bestows a certain honorable, consequential weight to 30, where you “assume your future shape, take your place in society, embrace a profession.”

The convenient thing about celebrating my birthday on December 31 is that the new calendar year corresponds perfectly with the next year of my life. It’s made me monstrous in a very particular way: as soon as December begins, I start soliciting people’s reflections on the old year, and their resolutions for the next. I’m one of those “terminally sentimental” types, as the writer Dan Sheehan described in his newsletter today, for whom “the end of the year is a bit of a bacchanal.…here's a real joy in having everyone around you overtly indulging in something that feels like a guilty pleasure most of the time.”

Today I’m indulging in sentimentality by thinking about what I’ve learned from passing through “that fatal age of thirty.” If 2024 was for figuring out what “future shape” I should have—the designer, writer, person I want to become—then 2025, I think, is for committing to the slow, patient work of getting there.

I can’t think about commitment without falling back on a concept from my undergraduate years: the exploration–exploitation dilemma. (Exploitation, here, isn’t meant to have any moral or ethical charge!) The idea is quite simple: If you’re an agent in a particular environment, there are 2 strategies you can use to pursue valuable outcomes. The first strategy is to explore and try to evaluate all the opportunities available in your environment. The second strategy is to exploit the best opportunities you’ve find so far. Ideally, you’d exhaustively explore everything available to you, and then pick the opportunities that are objectively best. In practice, however, agents have limited time.

Here’s a less abstract articulation: You’re a person in the 21st century trying to live a meaningful life. The decisions you’ll have to make include:

What to study in undergrad: Do you exhaustively explore all the subjects available at your school, including ones you’d never heard about before arriving on campus? But if you spend too much time taking classes in 10 different disciplines, you’ll run out of funding/money/time and won’t be able to graduate alongside your peers. And you’ll feel embarrassed about being “behind”—especially when everyone around you seems so certain, and already preparing for the right work placements, internships, research positions and graduate schools.

What profession to pursue: Do you try out multiple professions to see which one suits you best? Or should you deepen your skills in the profession you’ve already tried out, and actually make progress in your career? And what if some professions feel very different 1 year in, 5 years in, 10 years in?

Who to date: Should you make it work with the mostly-quite-nice person you’re already seeing? Or is your soulmate (for some definition of soulmate) still out there? Is your soulmate the other person you’ve been messaging on Hinge? Or is it someone you won’t meet until you move to a new city, make new friends, become a new self?1

In some situations, exploiting too early is disastrous; you’ve committed to something that wasn’t right for you. It’s useful to spend some time, especially in your youth, trying out different interests, ambitions, places, people. But exploring for too long is also risky—I think that’s what the well-known Sylvia Plath quote (the figs, the tree, the indecision) is all about.2

So there has to be some year where you decide: in this part of my life, I know what I value. I am choosing; I am committing. And now I’m thinking of another idea I came across years ago—it must have been after I’d finished my bachelor’s, when I first started working as a designer—about devoting a year to going deeper, not wider.

In 2017, the blogger David Cain wrote about a tradition he wanted to invent: a year “in which you don’t start anything new or acquire any new possessions you don’t need.” The purpose of this, Cain wrote, was to affirm the value of “what you already own or what you’ve already started.”

Completing this “depth year,” as Cain called it,

would be a hallmark of maturity, representing the transition between having reached adulthood chronologically and reaching it spiritually. You learn not to be so flippant with your aspirations.

By taking a whole year to go deeper instead of wider, you end up with a rich but carefully curated collection of personal interests, rather than the hoard of mostly-dormant infatuations that happens so easily in post-industrial society.

I was immediately taken with the concept of a depth year. But I’ve never managed to do it; I’ve spent my 20s exploring, not exploiting. I’ve tried ceramics and Crossfit and other things that seemed to have a cult-like community around them; I tolerated them or even liked them, but they weren’t my thing.

But now I feel I’ve found some of my things, and so 2025 is the year I switch strategies. I’ve been writing this newsletter for 1 year. Worn the same lipstick color for 3 years.3 Written my morning pages, as prescribed by Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, for 4 years. Dated the same woman for (almost!) 5 years. Had the same eyeglasses for 6 years—the frames, not the prescription, since my eyesight keeps getting worse. I didn’t know that these things would stick, but it’s nice to observe where my life has naturally become more consistent, more settled.

This may strike you as a tremendously boring way to live, especially for someone who’s always seeking out new books, ideas and encounters. And it’s true: since commitment reduces the choices you can make, it does produce monotony! But that monotony is what lets me make new choices elsewhere. My energy is reserved for going deeper; instead of figuring out what new interest to try, I’m going further in my existing ones, especially in my writing.

I don’t think it’s possible to face the exploration–exploitation dilemma without seeing commitment—to the right things, at the right time—as something that offers new forms of excitement, new forms of joy. Then again, I just got engaged.4

Three favorites to end the new year

The best book covers of 2024 ✦✧ A calendar concept to DIY ✦✧ My favorite EP of the year

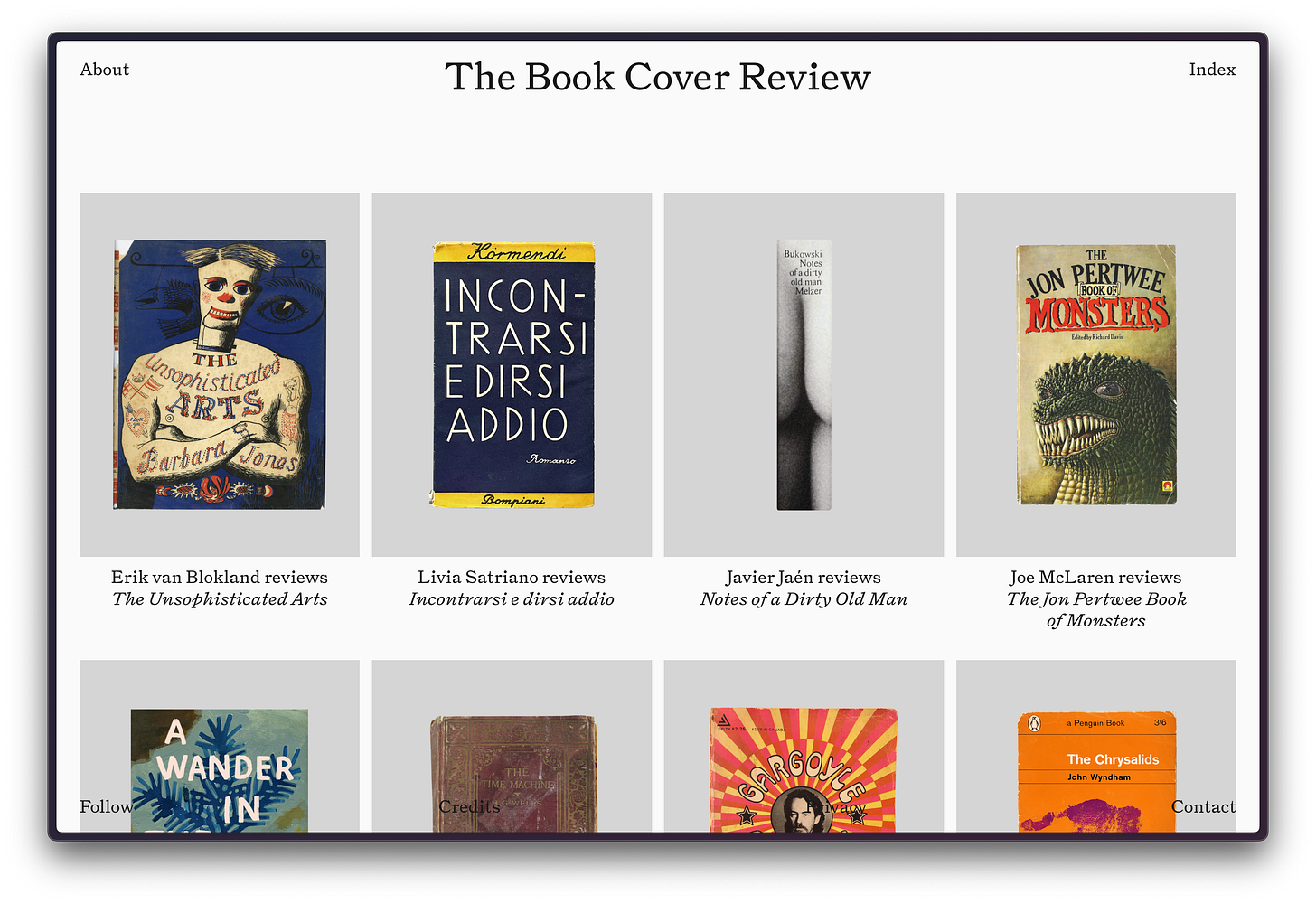

The best book covers of 2024 ✦

Matt Dorfman (who designed the elegant and evocative covers of Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume, translated by Barbara J. Haveland and published by New Directions this November) picked 12 of his favorite book covers of the year.

It includes covers designed by Na Kim, Pablo Delcan, and David Pearson—who also runs the excellent Book Cover Review website:

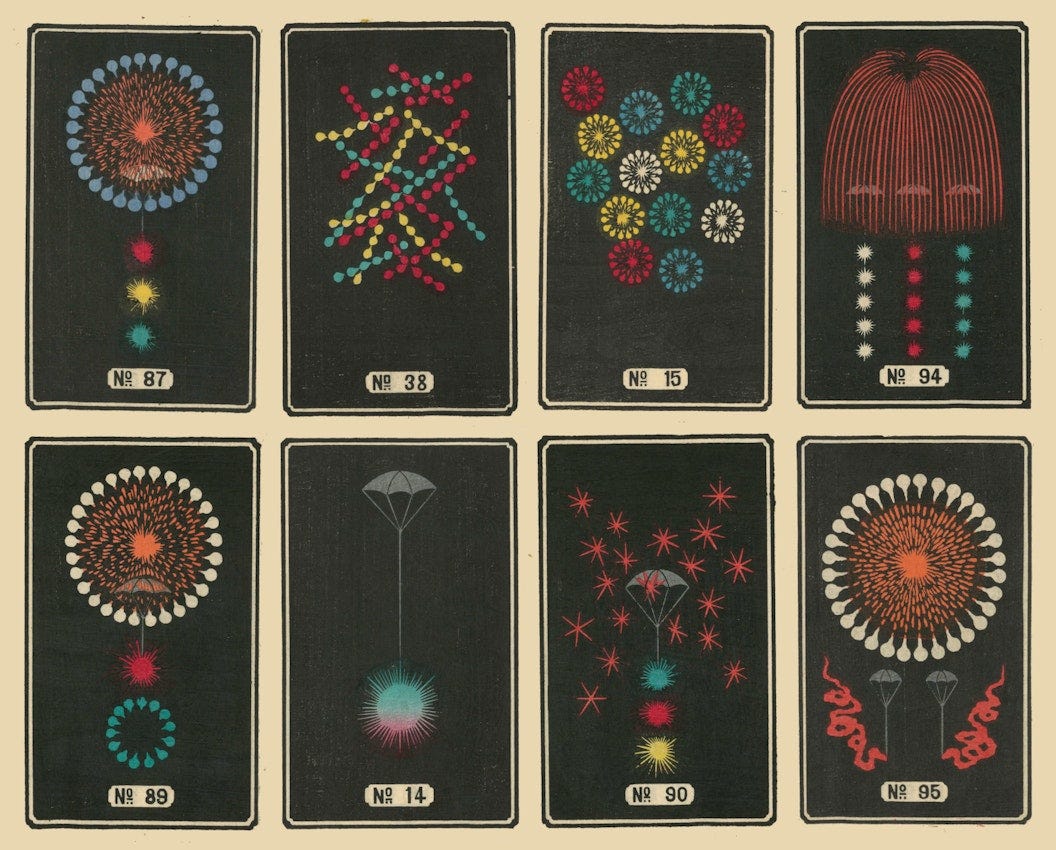

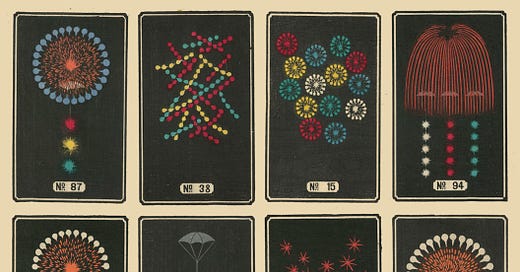

A calendar concept you can DIY ✦

I was too late to buy a Tezzo Suzuki calendar for 2025. Since 2012, the Japanese designer has created calendars featuring hand-drawn numbers for each day—here’s an excellent interview about his process.

But what if I took inspiration from Suzuki and drew my own calendar? It seems like such a fun way to try out new lettering styles—and if one day turns out a bit ugly, there’s always the next day to try again.

My favorite EP of 2024 ✦

I’ve been totally infatuated with this EP by by the producer and DJ Polygonia—the first track, “Jin Dou Yun,” has a lovely, reverential beauty to it that shifts between shimmering, naturalistic sounds (like water rushing along a riverbed of smoothed-out rocks) and pristine, exquisitely synthetic notes.

Dating can be modeled—in a limited but useful way—as an optimal stopping problem. Here’s an excerpt from the book Algorithms to Live By, by Brian Christian, Tom Griffiths, that discusses how “optimal stopping is the science of serial monogamy.”

These problems are interesting—not just mathematically but existentially—because they reflect the fundamental limitations of our lives. As Christian and Griffiths write (bolding mine):

The explicit premise of the optimal stopping problem is the implicit premise of what it is to be alive. It’s this that forces us to decide based on possibilities we’ve not yet seen, this that forces us to embrace high rates of failure even when acting optimally. No choice recurs. We may get similar choices again, but never that exact one. Hesitation — inaction — is just as irrevocable as action…

Intuitively, we think that rational decision-making means exhaustively enumerating our options, weighing each carefully, and then selecting the best. In practice, when the clock — or the ticker — is ticking, few aspects of decision-making, or of thinking more generally, are so important as one: when to stop.

In The Bell Jar, Plath writes (bolding mine):

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

Actually, my lipstick color (Byredo’s Lascaux) has just been discontinued, so I have to climb the great hill of Products again to find my new, ideal lipstick.

I’ve stolen this closing line from Andrea Long Chu’s “A Lover’s Theory of Marxism,” a review of Sally Rooney’s novel Intermezzo. The final paragraph of Chu’s review:

This may strike you as a surprisingly rosy account of mass consumption under capitalism, especially from a critic who keeps quoting Karl Marx. And it’s true: The fact that love consists of nothing but real relations between real people who all inhabit the same real world means that love, for a person or for a novel, will never be an escape from conventions or a relief from power. But this fact about love, what we might call its demoralizing specificity, is also the best evidence we have that love exists. I do not think we will ever be able to imagine love outside of capitalism unless we are first able to imagine love within it. Then again, I just got engaged.

Congratulations on your engagement! My metaphor for doing deeper (“doing” was a typo - I meant “going” - but some typos are meant to be), and committing is this: when I got married, I felt like all the windows that were trying to open on my laptop and were draining the hell out of my “hard drive” finally closed, except one, which instantly loaded. I know this isn’t the most romantic or even creative metaphor but it is the clearest. Too many windows leave us blind and trapped. You only need one through which to open yourself to the world, and vice versa. PS. I also recommend the perennial Cal Newport self help classic DEEP WORK.

Happy ✨champagne✨ birthday to you! This will undoubtedly be a magical year for you. xx