everything i read in march 2024

three books, essays old and new, and two perfect poems ✦

March is the month of spring—where we pass out of the months of quiet reflection, and leap into the months devoted to brightness, blooms on the trees, flowers in vases, a sense of possibility.

This was a hectic month for me: I moved apartments, had a major deadline at my day job, and finished an ambitious (but unwieldy) 5,000 word essay draft. My reading habits adapted accordingly: just 3 books and a lot of essays and poems.

Books

In March, I read 2 nonfiction books and 1 novel:

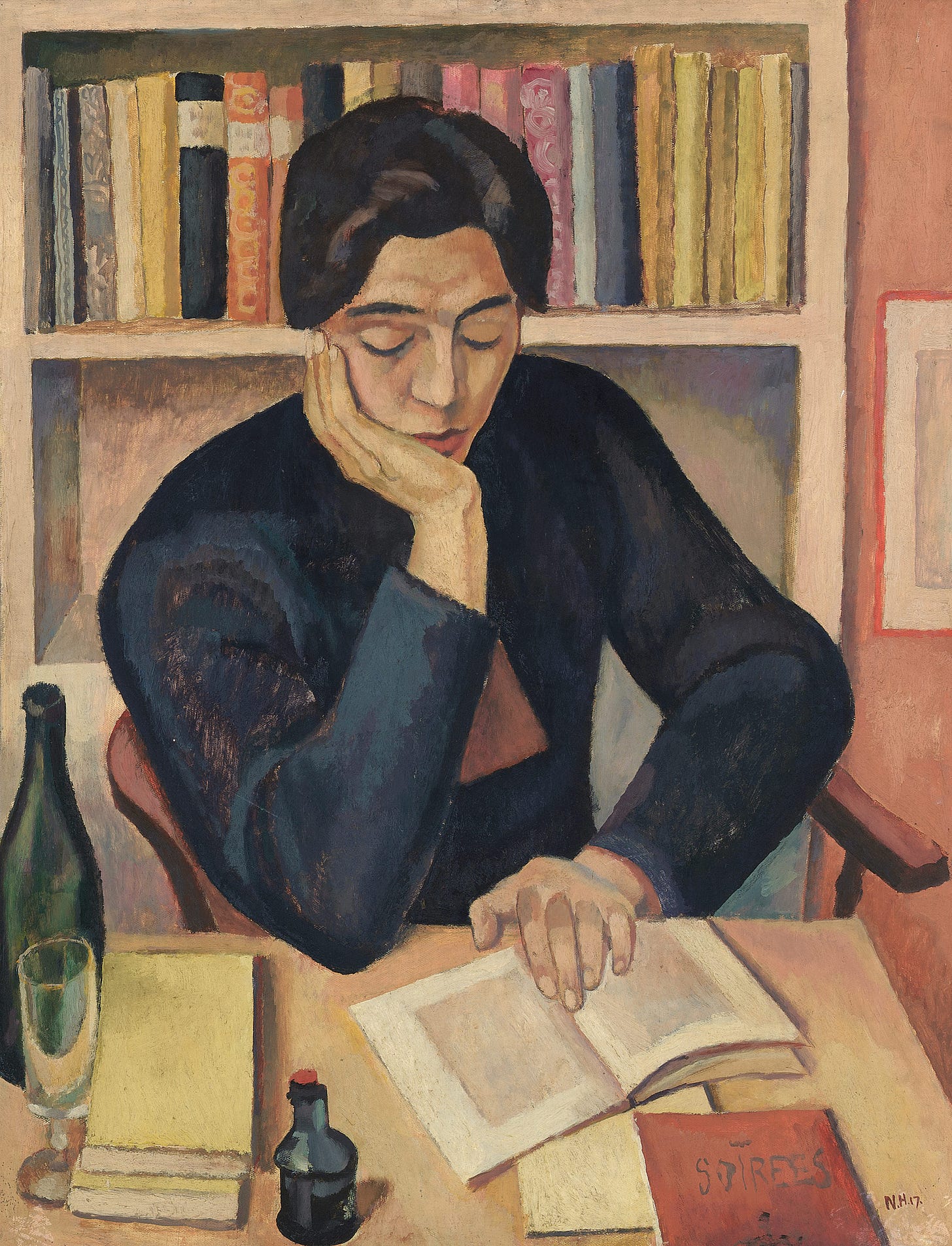

Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman and the City, a memoir by the eighty-year-old feminist critic, journalist, and teacher

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, where the film critic asks how we should relate to art by terrible men (such as Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, and Carl Andre)

Michel Houellebecq’s debut novel Whatever (originally published in French in 1994)

Vivian Gornick’s memoir ✦

I came across Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman and the City when a friend and I stopped by the Green Apple Books on Clement St. It has a beautiful, typographically crisp cover—one of my main requirements for a book I’m bringing home—but I’d already spent $95 on books that day, so instead I just borrowed an ebook of Gornick’s memoir from the San Francisco Public Library.

Gornick’s acute, relentless insight is almost painful to read. I was struck by this passage, where she describes abandoning her idealized fantasies of life and choosing reality instead:

Ever since I could remember, I had feared being found wanting. If I did the work I wanted to do, it was certain not to measure up; if I pursued the people I wanted to know, I was bound to be rejected; if I made myself as attractive as I could, I would still be ordinary looking. Around such damages to the ego a shrinking psyche had formed itself: I applied myself to my work, but only grudgingly; I'd make one move toward people I liked, but never two; I wore makeup but dressed badly. To do any or all of these things well would have been to engage heedlessly with life—love it more than I loved my fears—and this I could not do. What I could do, apparently, was daydream the years away: go on yearning for "things" to be different so that I would be different.

Turning sixty was like being told I had six months to live. Overnight, retreating into the refuge of a fantasized tomorrow became a thing of the past. Now there was only the immensity of the vacated present. Then and there I vowed to take seriously the task of filling it.

Claire Dederer’s essays on the art of terrible men ✦

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma expands on her hit 2017 essay for The Paris Review, “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” All the revelations about men who have raped women, sexually assaulted them, physically assaulted them? Is it possible to separate the art from the artist? Should we? Not really, Dederer says, but that’s also the less interesting question to ask. Instead of focusing on the biographies of these monstrous men, and deciding whether or not to “cancel” them, she’s much more interested in writing “an autobiography of the audience,” and the complex emotional experience of loving an artwork and feeling troubled by its creator.

I started reading Monsters on Jasmine Sun’s recommendation. It’s really great—and feels like a novel, exciting way to think about “cancel culture” and problematic artists. Too often, we’re so focused on what to do about them, the artists that have disappointed and betrayed the ideals represented in their art. Dederer argues that we should be focused on us—why a great artist’s terrible actions wound us so deeply, why we struggle to choose forgiveness or punishment, and what our obsession with monstrous artists says about our own feelings of guilt and shame.

The early chapters are, imo, the strongest, when Dederer uses a more narrow definition of “monsters” to discuss things like the beauty of Roman Polanski’s films versus the horror of his actions. Later chapters, which loosen the definition, are more perplexing. The chapter on Nabokov discusses the monstrosity of Humbert Humbert, the pedophilic protagonist of Lolita, and the discomfort people felt about Nabokov writing a monstrous character with a great deal of interiority. It doesn’t really connect that well to Dederer’s thesis, I think.

But the chapter where Dederer considers monstrous literary mothers—like Doris Lessing, the Nobel Prize in Literature laureate who famously left her husband and two oldest children so she could devote herself to her writing—is wonderful, and very movingly explores what level of selfishness is appropriate when you’re trying to be a great artist/writer and family member.

Michel Houellebecq’s debut novel (in conversation with an Amia Srinivasan essay) ✦

Lastly, I read Michel Houellebecq’s debut novel Whatever, published in 1994. Houellebecq is a prominent French writer and a bit of an enfant terrible—his novels are quite frank (sometimes unpleasantly so) about repugnant things: deeply-rooted misogyny, racism, Islamophobia. But I also found Whatever to be a remarkably precise portrait of social isolation and loneliness, a portrait that still feels relevant in 2024. The literary critic Adam Kirsch described Houellebecq as “a polarizing figure—admired for his provocations, disdained for his crudeness…[and]a writer of unusual prescience.” Whatever, Kirsch suggested, “understood what it meant to be an incel long before the term became common.”

Whatever is a novel about a 30 year old computer programmer who is remarkably lonely and passively suicidal. In gender and race (and beliefs about women…) I’m quite different than the narrator. Still, I found this passage very moving:

The problem is, it’s just not enough to live according to the rules. Sure, you manage to live according to the rules. Sometimes it’s tight, extremely tight, but on the whole you manage it. Your tax papers are up to date. Your bills paid on time. You never go out without your identity card (and the special little wallet for your Visa!). Yet you haven’t any friends…

Nevertheless, some free time remains. What’s to be done? How do you use your time? In dedicating yourself to helping people? But basically other people don’t interest you. Listening to records? That used to be a solution, but as the years go by you have to say that music moves you less and less…the fact is that nothing can halt the ever-increasing recurrence of those moments when your total isolation, the sensation of an all-consuming emptiness, the foreboding that your existence is nearing a painful and definitive end all combine to plunge you into a state of real suffering. And yet you haven’t always wanted to die.

Would I recommend Houellebecq? Yes—if you want a really incredible portrait of contemporary isolation, the banality of corporate life, the struggles of young adulthood, and recovering from a depressive despair…and you enjoy novels that don’t shy away from controversy, but instead depict them with a crude directness. I sometimes think that directness (where misogyny and racism are presented in an almost overt, factual way) can make a novel feel closer to real life. In real life, people are crude, unpleasant in their convictions, off-putting in their beliefs…and yet there’s nearly always a thread of empathy connecting us to them.

If you’re curious about Houellebecq’s style, btw—I enjoyed this post by JR, which discusses 6 Houellebecq novels and the overriding themes of his work:

A few weeks after I read Whatever, I also revisited he feminist philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s 2018 essay for the LRB, “Does anyone have the right to sex?”, which is also about incels. Srinivasan’s essay and Houellebecq’s novel have some very interesting arguments in common:

In contemporary society, liberal capitalist norms of free market exchange have been extended to sexuality;

Doing so has been psychologically damaging to individuals who are, for various reasons, now deemed as undesirable

As Srinivasan writes:

Sex is no longer morally problematic or unproblematic: it is instead merely wanted or unwanted. In this sense, the norms of sex are like the norms of capitalist free exchange…it would be disingenuous to make nothing of the convergence, however unintentional, between sex positivity and liberalism in their shared reluctance to interrogate the formation of our desires.

But the two writers disagree in who they focus on. Houellebecq focuses on men who are undesirable to women because they’re generically ugly or pathetic in some way—the classic incel figure. But Amia Srinivasan is interested in people more generally, who are undesirable because of racist and ableist sexual preferences. Srinivasan argues that if we see our sexual desires as purely innate and unpolitical, then “we are pushed towards a naturalisation of sexual preference” that might be quite patriarchal and racist.

Still reading ✦

As I mentioned in my February reading roundup, I’m slowly picking through the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s magnum opus, Distinction. It’s one of those revelatory books where I'm almost upset that I haven’t read it already. It kind of feels like Bourdieu studied and surveyed basically everything there is to know about social class, status, cultural capital versus economic capital…hoping to write more about him soon! (And endlessly grateful for my three-person BOURDIEU CHAT where we text each other favorite quotes.)

Essays

Four notable essays from this month, on age gaps; art and politics; Émile Zola; and doing great work when you don’t feel very smart.

Yes, I read The Cut's age gap essay ✦

Obviously, I read that viral essay on age-gap relationships: “The Case for Marrying an Older Man” by Grazie Sophia Christie, who met her wealthy French finance husband when she was 20 and he was 30. Since everyone on the internet has already published their take, I’ll be brief with mine.

I was struck by this passage, where Christie describes how nice it is to have a husband who is fully-formed and can mold you into a capable adult—compared to a same-age relationship where both people have to become adults together.

At 20, I had felt daunted by the project of becoming my ideal self, couldn’t imagine doing it in tandem with someone, two raw lumps of clay trying to mold one another and only sullying things worse. I’d go on dates with boys my age and leave with the impression they were telling me not about themselves but some person who didn’t exist yet and on whom I was meant to bet regardless. My husband struck me instead as so finished, formed…

My husband isn’t my partner. He’s my mentor, my lover, and, only in certain contexts, my friend. I’ll never forget it, how he showed me around our first place like he was introducing me to myself: This is the wine you’ll drink, where you’ll keep your clothes, we vacation here, this is the other language we’ll speak, you’ll learn it, and I did…I am the work in progress…When I searched for my first job, at 21…He had wisdom to impart, contacts with whom he arranged coffees…Meanwhile, I took calls from a dear friend who had a boyfriend her age. Both savagely ambitious, hyperclose and entwined in each other’s projects…every time she called me, I hung up with the distinct feeling that too much was happening at the same time: both learning to please a boss; to forge more adult relationships with their families; to pay bills and taxes and hang prints on the wall.

To Christie, embarking on a shared project of becoming adults together, maturing, growing, self-actualizing—all that seems hard! And stressful! Why not let an older (and very, very wealthy) man do it all for you? But it’s honestly such a strange framing to me—and if I’m being honest, I think it’s a tragic and pathetic framing.

To me, her friend’s relationship sounds really lovely—not the “savagely ambitious” part, necessarily, but being “entwined in each other’s projects.” Because that’s always what I’ve wanted from a partnership, and intimate friendships, too. I want to become a self I can admire and respect, and I want to struggle towards that goal alongside people who get it.

I thought BDM described it perfectly in a recent Substack post:

what your friend is doing is called growing up and there aren’t any shortcuts to that. You can grow up just the same as a stay at home wife—it’s not about career girlbossing. It’s about recognizing yourself as a moral agent who can make judgments and accept consequences. It’s extremely exhausting to be an agent but you know that’s life as a human being. It is wrong, as in a kind of sin, to hand it over to somebody else in this way, and it’s worse to take it.

On politically significant art and literature ✦

I loved Peter Weiss’s “The Necessary Decision: Ten Working Theses of an Author in the Divided World,” a remarkable essay from the 1960s about politics and art. Weiss was an avant-garde writer, artist, and filmmaker with deep political commitments: he denounced America’s war in Vietnam and was part of the anticapitalist Left Party in Sweden. It’s a short essay, barely 4 pages long, and vigorously argues for politically engaged art:

In this world the decision is taken. The propertied of the earth, a rather small group, take daily troubles to confirm their places and defend them. Having turned the postwar chaos to their advantage and enriching themselves enormously once again, they now look upon the awakening energies of the plundered peoples. The spectre that is rising before them haunts not only Europe, but wherever they look. Everywhere they build their bastions, in Africa, Asia or Latin America, the national liberation movements are growing and will not be halted…

[A]rt without commitment amounts to arrogance, considering that in those countries where the relations based on property and racism are maintained, the prisons are filled with the tortured fighters for justice and equality. All of my artistic successes achieved in supposed freedom are brought into sharp contrast by the misery that exists in most of the world.

Brandon Taylor stans and Francophiles unite ✦

Brandon Taylor is an American novelist who writes great literary criticism, and his essay for the LRB on Émile Zola is just incredible. Love the opening paragraph especially, which comments on the difficulty of even writing the piece in the first place:

When I agreed to write about Les Rougon-Macquart, Émile Zola’s cycle of twenty novels, published between 1871 and 1893, I imagined it would take six months, after which I would write an amusing little essay about how we should all read more Zola. This is not what happened. It took me two years. In that time, I had two books published, wrote another two books, moved from Iowa City to New York, taught myself film photography, became a professor of creative writing and an acquiring editor for a small press, adapted one of my novels for film, wrote a pilot for television, went on antidepressants, increased my dosage of antidepressants, stopped drinking coffee after 3 p.m., resumed tennis and table tennis lessons, and had my glasses prescription increased twice.

I really need to read Zola! I’m especially interested in Nana, the 9th novel in the cycle. One one of my favorite tiny artist book imprints, Sharon Kivland’s Ma Bibliothèque, has a great little publication called Reading Nana: An Experimental Novel, which seems like the perfect companion…but surely I need to read the actual Nana before I read about someone reading Nana?

How to do great work as an ordinary person:

My girlfriend and I have been obsessed with this post by Adaobi:

The title is kind of funny. In a painful way. I’ve always been afraid, horribly and terribly afraid, that I’m not that smart and I’m not very good at things and I’m also not that hard-working at all…so how am I going to design and write great things? While Adaobi’s post feels more obviously applicable to working a corporate job, certain bits feel especially useful to working on an artistic or literary practice as well:

Bring a sense of urgency & move fast. If you think about it, most deadlines are arbitrary, and smart & talented people know this…[and] may not feel a real sense of urgency to move faster. Try to counteract this energy…moving faster increases the likelihood that work will actually get done, and also opens you up…up to a lot more opportunities along the way. Most likely because you are “prepared” when you meet luck, or something along those lines.

This year I’m feeling a great deal of urgency about my writing. Ten hours a week, which usually happens at 6am before I go to work, at 6pm after I return home, and over the weekend. A Substack post (nearly) every week. 3–5 pitches a month to publications that I think are too good for me. (It’s wildly exciting when they write back.)

I want to be really, really, really good at writing essays and criticism. Having arbitrary deadlines for myself—writing here, writing for publications—is just the method I’ve chosen to get better.

Poetry

I am obsessed with the inaugural issue of atmospheric, a quarterly literary magazine founded and edited by Anthony Garrett (who I’m very grateful to know through PROUST CHAT) and Joely Fitch.

Every! single! poem! included! feels like the most beautiful poem I’ve read in a very, very long time. But I can especially recommend Isabella Streffen’s “Cyanometer for my Heart”, with beautiful images of different blues—

the blues of 16mm film of the ocean, the nitrate rush, the slow dissolve, the slicked celluloid glaze

it’s the sky opened like a secret in a mouth

it’s the shot silk of a lilacked bruise

—and the brief, transcendent poems by Tom Snarsky, like the humbly titled, 3-sentence “Poem”:

The ewe rejects her lamb

& so anticipates

All philosophy

Interviews

I am a devoted reader of literature in translation—which means I am totally reliant and profoundly grateful to all the literary translators working to bring great Norwegian, Taiwanese, Romanian, Korean, &c novels to the English-speaking world.1

So of course I loved this interview with Anton Hur, who translates Korean literature into English, for BOMB Magazine. Lots of fascinating little details on how literary translation happens: How translators pick their books, how they get book deals, what the career path of a translator looks like…and what makes for an easy or hard-to-translate book.

Tweets

The literary scholar and historian Dan Sinykin ran an informal Twitter survey asking his followers about their favorite literary criticism publications and writers. The top 7 publications were (in order): Bookforum, LRB, NYRB, LA Review of Books, The New Yorker, the New Left Review’s Sidecar blog…and the Cleveland Review. Incidentally, the Cleveland Review is where I published my first book review, on Mieko Kanai’s Mild Vertigo.

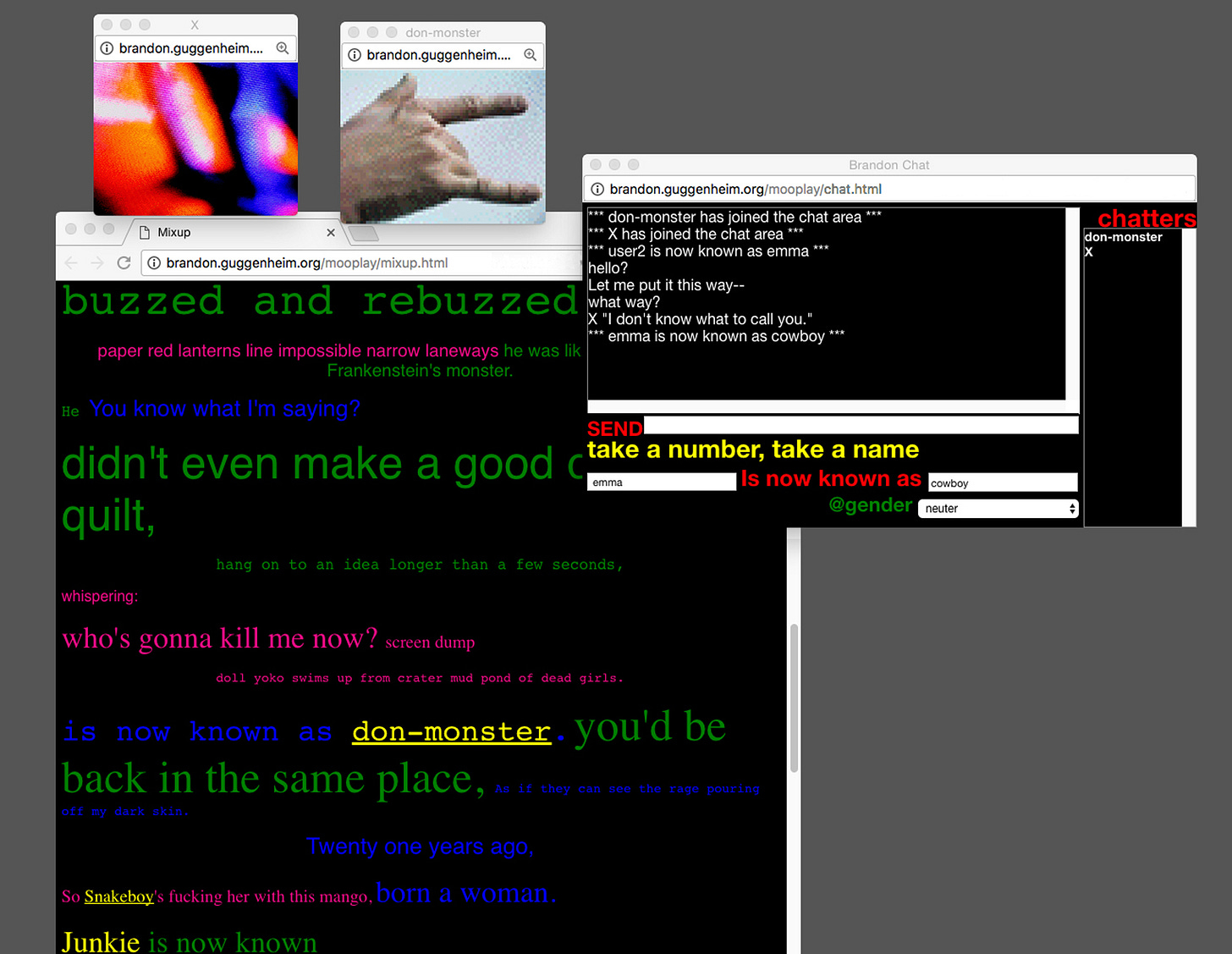

The artist and educator Taeyoon Choi (also a cofounder of the School for Poetic Computation, where I’m taking a class this spring!) has this great little Twitter thread about Nam June Paik, one of my favorite artists. Choi touches on how new media art pieces—Paik used a lot of old CRT monitors, projectors, and other equipment—can become “no longer functional…exist[ing] in a strange extension of life support” due to their aging hardware and software. It made me think of this fascinating project that the Guggenheim did in 2017 to restore the artist Shu Lea Cheang’s web art piece Brandon, which was online between 1998–9:

Brandon was the first of three web artworks that entered the museum’s permanent collection in the early days of the Internet. Over the years, the fast-evolving technological landscape of the web caused an increasing number of Brandon’s features to fail: Certain pages and data were no longer accessible; text and image animations no longer displayed properly; and many internal and external links were broken. Just like any other website, Brandon…can only execute its programmed, functional, and aesthetic behaviors if browsers and server environments support its underlying technologies and if embedded links are functioning.

The Guggenheim asked faculty and students from NYU’s computer science department to help conserve and restore the piece. It’s so fascinating to think about art conservation not just for paintings, but for websites! In the case of Brandon, the restoration team analyzed the source code and carefully rebuilt all the functionality that relied on outdated Java applets and deprecated HTML techniques like the

<blink>tag. Here’s a screenshot of the restored web artwork:

There are now 600 people (❣️) signed up to receive these posts. I’m honestly very touched and gratified that you’re all here, and that so many of you have commented to share your experiences with literature, art, writing, design, philosophy, psychoanalysis, and other topics.

Thank you, and be well this April!

I’ve always found it cute to stylize et cetera not as etc. but the more charmingly archaic &c…who doesn’t love a gratuitous ampersand? Although I’m not sure if you’re still supposed to put the period after it? Is it &c. or &c? If you know, please DM me immediately.

Your newsletter is so rich and nourishing and inspiring! Thanks for what you do ❤️

Two comments:

1) On Bourdieu, I found Distinction really difficult to understand. On the advice of a Bourdieu scholar, I took the shortcut of reading his essay "Forms of Capital."

I wrote a post about different types of capital, including a link to that essay on the bottom of my post.

https://robertsdavidn.substack.com/p/wealth-is-merely-one-form-of-capital

2) On the Cut article, your and BDM's take was more expansive and incisive than my own. Thanks for that. Since the author was also focused on the danger of losing her youthful beauty, I observed that many women grow more beautiful with age, and as men age, some men (me!) are more attracted to older women.